Bamboo

Bamboos /bæmˈbuː/ (![]()

| Bamboo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Bamboo forest in Arashiyama, Kyoto, Japan | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Clade: | BOP clade |

| Subfamily: | Bambusoideae Luerss. |

| Tribes | |

| Diversity[1] | |

| >1,462 (known species) species in 115 genera | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

In bamboo, as in other grasses, the internodal regions of the stem are usually hollow and the vascular bundles in the cross-section are scattered throughout the stem instead of in a cylindrical arrangement. The dicotyledonous woody xylem is also absent. The absence of secondary growth wood causes the stems of monocots, including the palms and large bamboos, to be columnar rather than tapering.[3]

Bamboos include some of the fastest-growing plants in the world,[4] due to a unique rhizome-dependent system. Certain species of bamboo can grow 910 mm (36 in) within a 24-hour period, at a rate of almost 40 mm (1 1⁄2 in) an hour (a growth around 1 mm every 90 seconds, or 1 inch every 40 minutes).[5] Giant bamboos are the largest members of the grass family.

Bamboos are of notable economic and cultural significance in South Asia, Southeast Asia and East Asia, being used for building materials, as a food source, and as a versatile raw product. Bamboo, like wood, is a natural composite material with a high strength-to-weight ratio useful for structures.[6] Bamboo's strength-to-weight ratio is similar to timber, and its strength is generally similar to a strong softwood or hardwood timber.[7][8]

Systematics and taxonomy

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phylogeny of the bamboo within the BOP clade of grasses, as suggested by analyses of the whole of Poaceae[9] and of the bamboos in particular.[1] |

| Bamboo | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.svg.png) "Bamboo" in ancient seal script (top) and regular script (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 竹 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 대나무 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 竹 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bamboos have long been considered the most primitive grasses, mostly because of the presence of bracteate, indeterminate inflorescences, "pseudospikelets", and flowers with three lodicules, six stamens, and three stigmata.[10] Following more recent molecular phylogenetic research, many tribes and genera of grasses formerly included in the Bambusoideae are now classified in other subfamilies, e.g. the Anomochlooideae, the Puelioideae, and the Ehrhartoideae. The subfamily in its current sense belongs to the BOP clade of grasses, where it is sister to the Pooideae (bluegrasses and relatives).[9]

The bamboos comprise three clades classified as tribes, and these strongly correspond with geographic divisions representing the New World herbaceous species (Olyreae), tropical woody bamboos (Bambuseae), and temperate woody bamboos (Arundinarieae). The woody bamboos do not form a monophyletic group; instead, the tropical woody and herbaceous bamboos are sister to the temperate woody bamboos.[1][9] Altogether, more than 1,400 species are placed in 115 genera.[1]

21 genera:

- Subtribe Buergersiochloinae

- one genus: Buergersiochloa.

- Subtribe Olyrineae

- 17 genera: Agnesia, Arberella, Cryptochloa, Diandrolyra, Ekmanochloa, Froesiochloa, Lithachne, Maclurolyra, Mniochloa, Olyra, Parodiolyra, Piresiella, Raddia, Raddiella, Rehia, Reitzia (syn. Piresia), Sucrea.

- Subtribe Parianinae

73 genera:

- Subtribe Arthrostylidiinae:

- 15 genera: Actinocladum, Alvimia, Arthrostylidium, Athroostachys, Atractantha, Aulonemia, Cambajuva, Colanthelia, Didymogonyx, Elytrostachys, Filgueirasia, Glaziophyton, Merostachys, Myriocladus, Rhipidocladum.

- Subtribe Bambusinae:

- 17 genera:Bambusa, Bonia, Cochinchinochloa, Dendrocalamus, Fimbribambusa, Gigantochloa, Maclurochloa, Melocalamus, Neomicrocalamus, Oreobambos, Oxytenanthera, Phuphanochloa, Pseudoxytenanthera, Soejatmia, Thyrsostachys, Vietnamosasa, Yersinochloa.

- Subtribe Chusqueinae:

- one genus:Chusquea.

- Subtribe Dinochloinae:

- 7 genera:Cyrtochloa, Dinochloa, Mullerochloa, Neololeba, Pinga, Parabambusa, Sphaerobambos.

- Subtribe Greslaniinae:

- one genus:Greslania.

- Subtribe Guaduinae:

- 5 genera:Apoclada, Eremocaulon, Guadua, Olmeca, Otatea.

- Subtribe Hickeliinae:

- 9 genera:Cathariostachys, Decaryochloa, Hickelia, Hitchcockella, Nastus, Perrierbambus, Sirochloa, Sokinochloa, Valiha.

- Subtribe Holttumochloinae:

- 3 genera:Holttumochloa, Kinabaluchloa, Nianhochloa.

- Subtribe Melocanninae:

- 9 genera:Annamocalamus, Cephalostachyum, Davidsea, Melocanna, Neohouzeaua, Ochlandra, Pseudostachyum, Schizostachyum, Stapletonia.

- Subtribe Racemobambosinae:

- 3 genera:Chloothamnus, Racemobambos, Widjajachloa.

- Subtribe Temburongiinae:

- one genus:Temburongia.

- incertae sedis

- 2 genera:Ruhooglandia, Temochloa.

31 genera: Acidosasa, Ampelocalamus, Arundinaria, Bashania, Bergbambos, Chimonobambusa, Chimonocalamus, Drepanostachyum, Fargesia, Ferrocalamus, Gaoligongshania, Gelidocalamus, Himalayacalamus, Indocalamus, Indosasa, Kuruna, Oldeania, Oligostachyum, Phyllostachys, Pleioblastus, Pseudosasa, Sarocalamus, Sasa, Sasaella, Sasamorpha, Semiarundinaria, Shibataea, Sinobambusa, Thamnocalamus, Vietnamocalamus, Yushania.

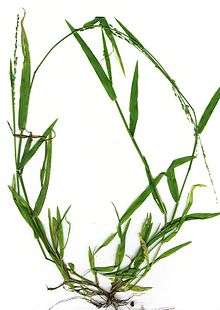

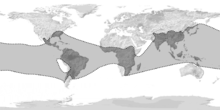

Distribution

Most bamboo species are native to warm and moist tropical and to warm temperate climates.[11] However, many species are found in diverse climates, ranging from hot tropical regions to cool mountainous regions and highland cloud forests.

In the Asia-Pacific region they occur across East Asia, from north to 50 °N latitude in Sakhalin,[12] to south to northern Australia, and west to India and the Himalayas. China, Japan, Korea, India and Australia, all have several endemic populations.[13] They also occur in small numbers in sub-Saharan Africa, confined to tropical areas, from southern Senegal in the north to southern Mozambique and Madagascar in the south.[14] In the Americas, bamboo has a native range from 47 °S in southern Argentina and the beech forests of central Chile, through the South American tropical rainforests, to the Andes in Ecuador near 4,300 m (14,000 ft). Bamboo is also native through Central America and Mexico, northward into the Southeastern United States.[15] Canada and continental Europe are not known to have any native species of bamboo.[16] As garden plants, many species grow readily outside these ranges, including most of Europe and the United States.

Recently, some attempts have been made to grow bamboo on a commercial basis in the Great Lakes region of east-central Africa, especially in Rwanda.[17] In the United States, several companies are growing, harvesting, and distributing species such as Phyllostachys nigra (Henon) and Phyllostachys edulis (Moso).[18]

- Phyllostachys pubescens in Batumi Botanical Garden

Bamboo forest in Arashiyama

Bamboo forest in Arashiyama

Bamboo forest in KwaZulu-Natal

Bamboo forest in KwaZulu-Natal

- Bamboo forest in New Jersey

Bamboo forest in France

Bamboo forest in France Bamboo forest in Taiwan

Bamboo forest in Taiwan

Ecology

The two general patterns for the growth of bamboo are "clumping", and "running", with short and long underground rhizomes, respectively. Clumping bamboo species tend to spread slowly, as the growth pattern of the rhizomes is to simply expand the root mass gradually, similar to ornamental grasses. "Running" bamboos, though, need to be controlled during cultivation because of their potential for aggressive behavior. They spread mainly through their rhizomes, which can spread widely underground and send up new culms to break through the surface. Running bamboo species are highly variable in their tendency to spread; this is related to both the species and the soil and climate conditions. Some can send out runners of several metres a year, while others can stay in the same general area for long periods. If neglected, over time, they can cause problems by moving into adjacent areas.

Bamboos include some of the fastest-growing plants on Earth, with reported growth rates up to 910 mm (36 in) in 24 hours.[5] However, the growth rate is dependent on local soil and climatic conditions, as well as species, and a more typical growth rate for many commonly cultivated bamboos in temperate climates is in the range of 30–100 mm (1.2–3.9 in) per day during the growing period. Primarily growing in regions of warmer climates during the late Cretaceous period, vast fields existed in what is now Asia. Some of the largest timber bamboo can grow over 30 m (98 ft) tall, and be as large as 250–300 mm (10–12 in) in diameter. However, the size range for mature bamboo is species-dependent, with the smallest bamboos reaching only several inches high at maturity. A typical height range that would cover many of the common bamboos grown in the United States is 4.5–12 m (15–39 ft), depending on species. Anji County of China, known as the "Town of Bamboo", provides the optimal climate and soil conditions to grow, harvest, and process some of the most valued bamboo poles available worldwide.

Unlike all trees, individual bamboo culms emerge from the ground at their full diameter and grow to their full height in a single growing season of three to four months. During this time, each new shoot grows vertically into a culm with no branching out until the majority of the mature height is reached. Then, the branches extend from the nodes and leafing out occurs. In the next year, the pulpy wall of each culm slowly hardens. During the third year, the culm hardens further. The shoot is now a fully mature culm. Over the next 2–5 years (depending on species), fungus begins to form on the outside of the culm, which eventually penetrates and overcomes the culm. Around 5–8 years later (species- and climate-dependent), the fungal growths cause the culm to collapse and decay. This brief life means culms are ready for harvest and suitable for use in construction within about three to seven years. Individual bamboo culms do not get any taller or larger in diameter in subsequent years than they do in their first year, and they do not replace any growth lost from pruning or natural breakage. Bamboo has a wide range of hardiness depending on species and locale. Small or young specimens of an individual species produce small culms initially. As the clump and its rhizome system mature, taller and larger culms are produced each year until the plant approaches its particular species limits of height and diameter.

Many tropical bamboo species die at or near freezing temperatures, while some of the hardier temperate bamboos can survive temperatures as low as −29 °C (−20 °F). Some of the hardiest bamboo species can be grown in USDA plant hardiness zone 5, although they typically defoliate and may even lose all above-ground growth, yet the rhizomes survive and send up shoots again the next spring. In milder climates, such as USDA zone 7 and above, most bamboo remain fully leafed out and green year-round.

Mass flowering

Bamboos seldom and unpredictably flower and the frequency of flowering varies greatly from species to species. Once flowering takes place, a plant declines and often dies entirely. In fact, many species only flower at intervals as long as 65 or 120 years. These taxa exhibit mass flowering (or gregarious flowering), with all plants in a particular 'cohort' flowering over a several-year period. Any plant derived through clonal propagation from this cohort will also flower regardless of whether it has been planted in a different location. The longest mass flowering interval known is 130 years, and it is for the species Phyllostachys bambusoides (Sieb. & Zucc.). In this species, all plants of the same stock flower at the same time, regardless of differences in geographic locations or climatic conditions, and then the bamboo dies. The lack of environmental impact on the time of flowering indicates the presence of some sort of "alarm clock" in each cell of the plant which signals the diversion of all energy to flower production and the cessation of vegetative growth.[19] This mechanism, as well as the evolutionary cause behind it, is still largely a mystery.

One hypothesis to explain the evolution of this semelparous mass flowering is the predator satiation hypothesis, which argues that by fruiting at the same time, a population increases the survival rate of its seeds by flooding the area with fruit, so even if predators eat their fill, seeds will still be left over. By having a flowering cycle longer than the lifespan of the rodent predators, bamboos can regulate animal populations by causing starvation during the period between flowering events. Thus, the death of the adult clone is due to resource exhaustion, as it would be more effective for parent plants to devote all resources to creating a large seed crop than to hold back energy for their own regeneration.[20]

Another, the fire cycle hypothesis, states that periodic flowering followed by death of the adult plants has evolved as a mechanism to create disturbance in the habitat, thus providing the seedlings with a gap in which to grow. This argues that the dead culms create a large fuel load, and also a large target for lightning strikes, increasing the likelihood of wildfire.[21] Because bamboos can be aggressive as early successional plants, the seedlings would be able to outstrip other plants and take over the space left by their parents.

However, both have been disputed for different reasons. The predator satiation hypothesis does not explain why the flowering cycle is 10 times longer than the lifespan of the local rodents, something not predicted. The bamboo fire cycle hypothesis is considered by a few scientists to be unreasonable; they argue[22] that fires only result from humans and there is no natural fire in India. This notion is considered wrong based on distribution of lightning strike data during the dry season throughout India. However, another argument against this is the lack of precedent for any living organism to harness something as unpredictable as lightning strikes to increase its chance of survival as part of natural evolutionary progress.[23]

More recently, a mathematical explanation for the extreme length of the flowering cycles has been offered, involving both the stabilising selection implied by the predator satiation hypothesis and others, and the fact that plants that flower at longer intervals tend to release more seeds.[24][25] The hypothesis claims that bamboo flowering intervals grew by integer multiplication. A mutant bamboo plant flowering at a noninteger multiple of its population's flowering interval would release its seeds alone, and would not enjoy the benefits of collective flowering (such as protection from predators). However, a mutant bamboo plant flowering at an integer multiple of its population's flowering interval would release its seeds only during collective flowering events, and would release more seeds than the average plant in the population. It could, therefore, take over the population, establishing a flowering interval that is an integer multiple of the previous flowering interval. The hypothesis predicts that observed bamboo flowering intervals should factorize into small prime numbers.

The mass fruiting also has direct economic and ecological consequences, however. The huge increase in available fruit in the forests often causes a boom in rodent populations, leading to increases in disease and famine in nearby human populations. For example, devastating consequences occur when the Melocanna bambusoides population flowers and fruits once every 30–35 years[26] around the Bay of Bengal. The death of the bamboo plants following their fruiting means the local people lose their building material; and the large increase in bamboo fruit leads to a rapid increase in rodent populations. As the number of rodents increases, they consume all available food, including grain fields and stored food, sometimes leading to famine. These rats can also carry dangerous diseases, such as typhus, typhoid, and bubonic plague, which can reach epidemic proportions as the rodents increase in number.[19][20] The relationship between rat populations and bamboo flowering was examined in a 2009 Nova documentary "Rat Attack".

In any case, flowering produces masses of seeds, typically suspended from the ends of the branches. These seeds give rise to a new generation of plants that may be identical in appearance to those that preceded the flowering, or they may produce new cultivars with different characteristics, such as the presence or absence of striping or other changes in coloration of the culms.

Several bamboo species are never known to set seed even when sporadically flowering has been reported. Bambusa vulgaris, Bambusa balcooa, and Dendrocalamus stocksii are common examples of such bamboo.[27]

Animal diet

Soft bamboo shoots, stems and leaves are the major food source of the giant panda of China, the red panda of Nepal, and the bamboo lemurs of Madagascar. Rats eat the fruits as described above. Mountain gorillas of Central Africa also feed on bamboo, and have been documented consuming bamboo sap which was fermented and alcoholic;[14] chimpanzees and elephants of the region also eat the stalks.

The larvae of the bamboo borer (the moth Omphisa fuscidentalis) of Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Yunnan, China feed off the pulp of live bamboo. In turn, these caterpillars are considered a local delicacy.

Allergenic potential

Gardeners working with bamboo plants have occasionally reported allergic reactions varying from no effects during previous exposures, to immediate itchiness and rash developing into red welts after several hours where the skin had been in contact with the plant (contact allergy), and in some cases into swollen eyelids and breathing difficulties (dyspnoea). A skin prick test using bamboo extract was positive for the immunoglobulin E (IgE) in an available case study.[28][29][30]

Cultivation

Although a few species of bamboo are always in flower at any given time, growing a specific bamboo typically requires obtaining plants as divisions of already-growing plants, rather than waiting for seeds to be produced.

Commercial timber

Timber is harvested from both cultivated and wild stands, and some of the larger bamboos, particularly species in the genus Phyllostachys, are known as "timber bamboos".

Harvesting

Bamboo used for construction purposes must be harvested when the culms reach their greatest strength and when sugar levels in the sap are at their lowest, as high sugar content increases the ease and rate of pest infestation. As compared to forest trees, bamboo species grow fast. Bamboo plantations can be readily harvested for a shorter period than tree plantations.[31]

Harvesting of bamboo is typically undertaken according to these cycles:

- Lifecycle of the culm: As each individual culm goes through a 5- to 7-year lifecycle, culms are ideally allowed to reach this level of maturity prior to full capacity harvesting. The clearing out or thinning of culms, particularly older decaying culms, helps to ensure adequate light and resources for new growth. Well-maintained clumps may have a productivity three to four times that of an unharvested wild clump. Consistent with the lifecycle described above, bamboo is harvested from two to three years through to five to seven years, depending on the species.

- Annual cycle: As all growth of new bamboo occurs during the wet season, disturbing the clump during this phase will potentially damage the upcoming crop. Also during this high-rainfall period, sap levels are at their highest, and then diminish towards the dry season. Picking immediately prior to the wet/growth season may also damage new shoots. Hence, harvesting is best a few months prior to the start of the wet season.

- Daily cycle: During the height of the day, photosynthesis is at its peak, producing the highest levels of sugar in sap, making this the least ideal time of day to harvest. Many traditional practitioners believe the best time to harvest is at dawn or dusk on a waning moon.

Leaching

Leaching is the removal of sap after harvest. In many areas of the world, the sap levels in harvested bamboo are reduced either through leaching or postharvest photosynthesis. For example:

- Cut bamboo is raised clear of the ground and leaned against the rest of the clump for one to two weeks until leaves turn yellow to allow full consumption of sugars by the plant.

- A similar method is undertaken, but with the base of the culm standing in fresh water, either in a large drum or stream to leach out sap.

- Cut culms are immersed in a running stream and weighted down for three to four weeks.

- Water is pumped through the freshly cut culms, forcing out the sap (this method is often used in conjunction with the injection of some form of treatment).

In the process of water leaching, the bamboo is dried slowly and evenly in the shade to avoid cracking in the outer skin of the bamboo, thereby reducing opportunities for pest infestation.

Durability of bamboo in construction is directly related to how well it is handled from the moment of planting through harvesting, transportation, storage, design, construction, and maintenance. Bamboo harvested at the correct time of year and then exposed to ground contact or rain will break down just as quickly as incorrectly harvested material.[32]

Maintenance of spreading runners

Regular observations at ground level indicate major growth directions and locations of rhizomes. In dry and hard soil conditions extending rhizomes will cause cracks in the soil surface. To facilitate rhizome maintenance it's best to dig a furrow around the bamboo planting or plant in a raised mound or bottomless lumber frame box. During "root pruning" of running bamboo the cut rhizomes are typically removed; however, rhizomes take a number of months to mature, and an immature, severed rhizome usually ceases growing if left in-ground. If any bamboo shoots come up outside of the bamboo area afterwards, their presence indicates the precise location of the removed rhizome. The fibrous roots that radiate from the rhizomes do not produce more bamboo.

Bamboo growth can be somewhat controlled by surrounding the plant or grove with a physical barrier. Typically, steel, concrete, and specially rolled HDPE plastic are used to create the barrier, which is placed in a 600– to 900-millimetre-deep ditch around the planting and angled out at the top to direct the rhizomes to the surface; this is only possible if the barrier is installed in a straight line. Regardless of size of area, blocking bamboo rhizomes as a solution to controlling running bamboo is detrimental to the health of the plant, and only temporary. Bamboo within barriers usually become rootbound after a few years and start to display the signs of any unhealthy containerized plant. In addition, rhizomes pile up against the barrier and often escape over the top or under the bottom. Strong rhizomes and tools can penetrate plastic easily, so care must be taken. In small areas, regular root pruning maintenance may be the best method for controlling the running bamboos. Barriers and edging are unnecessary for clump-forming bamboos, although these may eventually need to have portions removed if they become too large.

Lucky bamboo

The ornamental plant marketed as "lucky bamboo" is an entirely unrelated plant, Dracaena sanderiana. It is a resilient member of the lily family that grows in the dark, tropical rainforests of Southeast Asia and Africa. "Lucky bamboo" has long been associated with the Eastern practice of feng shui. Images of the plant widely available on the Web are often used to depict bamboo.

Invasive species

Phyllostachys species of bamboo are also considered invasive and illegal to sell or propagate in some areas of the US.[33] On a related note, Japanese knotweed is sometimes mistaken for a bamboo, but it grows wild and is considered an invasive species.

Uses

Culinary

Although the shoots (newly emerged culms) of bamboo contain a toxin taxiphyllin (a cyanogenic glycoside) that produces cyanide in the gut, proper processing renders them edible. They are used in numerous Asian dishes and broths, and are available in supermarkets in various sliced forms, in both fresh and canned versions. The golden bamboo lemur ingests many times the quantity of the taxiphyllin-containing bamboo that would kill a human.

The bamboo shoot in its fermented state forms an important ingredient in cuisines across the Himalayas. In Assam, India, for example, it is called khorisa. In Nepal, a delicacy popular across ethnic boundaries consists of bamboo shoots fermented with turmeric and oil, and cooked with potatoes into a dish that usually accompanies rice (alu tama (आलु तामा) in Nepali).

In Indonesia, they are sliced thin and then boiled with santan (thick coconut milk) and spices to make a dish called gulai rebung. Other recipes using bamboo shoots are sayur lodeh (mixed vegetables in coconut milk) and lun pia (sometimes written lumpia: fried wrapped bamboo shoots with vegetables). The shoots of some species contain toxins that need to be leached or boiled out before they can be eaten safely.

Pickled bamboo, used as a condiment, may also be made from the pith of the young shoots.

The sap of young stalks tapped during the rainy season may be fermented to make ulanzi (a sweet wine) or simply made into a soft drink. Bamboo leaves are also used as wrappers for steamed dumplings which usually contains glutinous rice and other ingredients.

Pickled bamboo shoots (Nepali: तामा tama) are cooked with black-eyed beans as a delicacy in Nepal. Many Nepalese restaurants around the world serve this dish as aloo bodi tama. Fresh bamboo shoots are sliced and pickled with mustard seeds and turmeric and kept in glass jar in direct sunlight for the best taste. It is used alongside many dried beans in cooking during winters. Baby shoots (Nepali: tusa) of a very different variety of bamboo (Nepali: निगालो Nigalo) native to Nepal is cooked as a curry in hilly regions.

.jpg)

In Sambalpur, India, the tender shoots are grated into juliennes and fermented to prepare kardi. The name is derived from the Sanskrit word for bamboo shoot, karira. This fermented bamboo shoot is used in various culinary preparations, notably amil, a sour vegetable soup. It is also made into pancakes using rice flour as a binding agent. The shoots that have turned a little fibrous are fermented, dried, and ground to sand-sized particles to prepare a garnish known as hendua. It is also cooked with tender pumpkin leaves to make sag green leaves.

In Konkani cuisine, the tender shoots (kirlu) are grated and cooked with crushed jackfruit seeds to prepare kirla sukke.

The Indian state of Sikkim has promoted bamboo water bottles to keep the state free from plastic bottles [34]

Kitchenware

The empty hollow in the stalks of larger bamboo is often used to cook food in many Asian cultures. Soups are boiled and rice is cooked in the hollows of fresh stalks of bamboo directly over a flame. Similarly, steamed tea is sometimes rammed into bamboo hollows to produce compressed forms of Pu-erh tea. Cooking food in bamboo is said to give the food a subtle but distinctive taste.

In addition, bamboo is frequently used for cooking utensils within many cultures, and is used in the manufacture of chopsticks. In modern times, some see bamboo tools as an ecofriendly alternative to other manufactured utensils.

Fuel

Bamboo charcoal has been traditionally used as fuel in China and Japan. Bamboo can also be utilized as a biofuel crop.[35][36]

Writing pen

In old times, people in India used hand made pens (known as Kalam) made from thin bamboo sticks (with diameters of 5–10 mm and lengths of 100–150 mm) by simply peeling them on one side and making a nib-like pattern at the end. The pen would then be dipped in ink for writing.

Fabric

Bamboo species Phyllostachys edulis is used extensively to produce fabric for clothing.

Bambooworking

Bamboo was used by humans for various purposes at a very early time. Categories of Bambooworking include:

Construction

Bamboo, like true wood, is a natural composite material with a high strength-to-weight ratio useful for structures.[6]

In its natural form, bamboo as a construction material is traditionally associated with the cultures of South Asia, East Asia, and the South Pacific, to some extent in Central and South America, and by extension in the aesthetic of Tiki culture. In China and India, bamboo was used to hold up simple suspension bridges, either by making cables of split bamboo or twisting whole culms of sufficiently pliable bamboo together. One such bridge in the area of Qian-Xian is referenced in writings dating back to 960 AD and may have stood since as far back as the third century BC, due largely to continuous maintenance.

Bamboo has also long been used as scaffolding; the practice has been banned in China for buildings over six stories, but is still in continuous use for skyscrapers in Hong Kong.[37] In the Philippines, the nipa hut is a fairly typical example of the most basic sort of housing where bamboo is used; the walls are split and woven bamboo, and bamboo slats and poles may be used as its support. In Japanese architecture, bamboo is used primarily as a supplemental or decorative element in buildings such as fencing, fountains, grates, and gutters, largely due to the ready abundance of quality timber.[38]

Textiles

Since the fibers of bamboo are very short (less than 3 mm or 1⁄8 in), they are not usually transformed into yarn by a natural process. The usual process by which textiles labeled as being made of bamboo are produced uses only rayon made from the fibers with heavy employment of chemicals. To accomplish this, the fibers are broken down with chemicals and extruded through mechanical spinnerets; the chemicals include lye, carbon disulfide, and strong acids.[39] Retailers have sold both end products as "bamboo fabric" to cash in on bamboo's current ecofriendly cachet; however, the Canadian Competition Bureau[40] and the US Federal Trade Commission,[41] as of mid-2009, are cracking down on the practice of labeling bamboo rayon as natural bamboo fabric. Under the guidelines of both agencies, these products must be labeled as rayon with the optional qualifier "from bamboo".[41]

As a writing surface

Bamboo was in widespread use in early China as a medium for written documents. The earliest surviving examples of such documents, written in ink on string-bound bundles of bamboo strips (or "slips"), date from the 5th century BC during the Warring States period. However, references in earlier texts surviving on other media make it clear that some precursor of these Warring States period bamboo slips was in use as early as the late Shang period (from about 1250 BC).

Bamboo or wooden strips were used as the standard writing material during the early Han dynasty, and excavated examples have been found in abundance.[42] Subsequently, paper began to displace bamboo and wooden strips from mainstream uses, and by the 4th century AD, bamboo slips had been largely abandoned as a medium for writing in China.

Bamboo fiber has been used to make paper in China since early times. A high-quality, handmade paper is still produced in small quantities. Coarse bamboo paper is still used to make spirit money in many Chinese communities.[43]

Bamboo pulps are mainly produced in China, Myanmar, Thailand, and India, and are used in printing and writing papers.[44] Several paper industries are surviving on bamboo forests. Ballarpur (Chandrapur, Maharstra) paper mills use bamboo for paper production. The most common bamboo species used for paper are Dendrocalamus asper and Bambusa blumeana. It is also possible to make dissolving pulp from bamboo. The average fiber length is similar to hardwoods, but the properties of bamboo pulp are closer to softwood pulps due to it having a very broad fiber length distribution.[44] With the help of molecular tools, it is now possible to distinguish the superior fiber-yielding species/varieties even at juvenile stages of their growth, which can help in unadulterated merchandise production.[45]

Weapons

Bamboo has often been used to construct weapons and is still incorporated in several Asian martial arts.

- A bamboo staff, sometimes with one end sharpened, is used in the Tamil martial art of silambam, a word derived from a term meaning "hill bamboo".

- Staves used in the Indian martial art of gatka are commonly made from bamboo, a material favoured for its light weight.

- A bamboo sword called a shinai is used in the Japanese martial art of kendo.

- Bamboo is used for crafting the bows, called yumi, and arrows used in the Japanese martial art kyūdō.

- Bamboo is sometimes used to craft the limbs of the longbow and recurve bow used in traditional archery, and to make superior weapons for bowhunting and target archery.

- The first gunpowder-based weapons, such as the fire lance, were made of bamboo.

- Bamboo was apparently used in East and South Asia as a means of torture.

Musical instruments

Other uses

Bamboo has traditionally been used to make a wide range of everyday utensils and cutting boards, particularly in Japan,[46] where archaeological excavations have uncovered bamboo baskets dating to the Late Jōmon period (2000–1000 BC).[47]

Bamboo has a long history of use in Asian furniture. Chinese bamboo furniture is a distinct style based on a millennia-long tradition, and bamboo is also used for floors due to its high hardness.[48]

Several manufacturers offer bamboo bicycles, surfboards, snowboards, and skateboards.[49][50]

Due to its flexibility, bamboo is also used to make fishing rods. The split cane rod is especially prized for fly fishing. Bamboo has been traditionally used in Malaysia as a firecracker called a meriam buluh or bamboo cannon. Four-foot-long sections of bamboo are cut, and a mixture of water and calcium carbide are introduced. The resulting acetylene gas is ignited with a stick, producing a loud bang. Bamboo can be used in water desalination. A bamboo filter is used to remove the salt from seawater.[51]

Many ethnic groups in remote areas that have water access in Asia use bamboo that is 3–5 years old to make rafts. They use 8 to 12 poles, 6–7 m (20–23 ft) long, laid together side by side to a width of about 1 m (3 ft). Once the poles are lined up together, they cut a hole crosswise through the poles at each end and use a small bamboo pole pushed through that hole like a screw to hold all the long bamboo poles together. Floating houses use whole bamboo stalks tied together in a big bunch to support the house floating in the water. Bamboo is also used to make eating utensils such as chopsticks, trays, and tea scoops.

The Song Dynasty (960–1279 AD) Chinese scientist and polymath Shen Kuo (1031–1095) used the evidence of underground petrified bamboo found in the dry northern climate of Yan'an, Shanbei region, Shaanxi province to support his geological theory of gradual climate change.[52][53]

Symbolism and culture

Bamboo's long life makes it a Chinese symbol of uprightness and an Indian symbol of friendship. The rarity of its blossoming has led to the flowers' being regarded as a sign of impending famine. This may be due to rats feeding upon the profusion of flowers, then multiplying and destroying a large part of the local food supply. The most recent flowering began in May 2006 (see Mautam). Bamboo is said to bloom in this manner only about every 50 years (see 28–60 year examples in FAO: 'gregarious' species table).

In Chinese culture, the bamboo, plum blossom, orchid, and chrysanthemum (often known as méi lán zhú jú 梅蘭竹菊 in Chinese) are collectively referred to as the Four Gentlemen. These four plants also represent the four seasons and, in Confucian ideology, four aspects of the junzi ("prince" or "noble one"). The pine (sōng 松), the bamboo (zhú 竹), and the plum blossom (méi 梅) are also admired for their perseverance under harsh conditions, and are together known as the "Three Friends of Winter" (歲寒三友 suìhán sānyǒu) in Chinese culture. The "Three Friends of Winter" is traditionally used as a system of ranking in Japan, for example in sushi sets or accommodations at a traditional ryokan. Pine (matsu 松 in Japanese) is of the first rank, bamboo (take 竹) is of second rank, and plum (ume 梅) is of the third.

The Bozo ethnic group of West Africa take their name from the Bambara phrase bo-so, which means "bamboo house". Bamboo is also the national plant of St. Lucia.

Attributions of character

Bamboo, one of the "Four Gentlemen" (bamboo, orchid, plum blossom and chrysanthemum), plays such an important role in traditional Chinese culture that it is even regarded as a behavior model of the gentleman. As bamboo has features such as uprightness, tenacity, and modesty, people endow bamboo with integrity, elegance, and plainness, though it is not physically strong. Countless poems praising bamboo written by ancient Chinese poets are actually metaphorically about people who exhibited these characteristics. An ancient poet, Bai Juyi (772–846), thought that to be a gentleman, a man does not need to be physically strong, but he must be mentally strong, upright, and perseverant. Just as a bamboo is hollow-hearted, he should open his heart to accept anything of benefit and never have arrogance or prejudice.

Bamboo is not only a symbol of a gentleman, but also plays an important role in Buddhism, which was introduced into China in the first century. As canons of Buddhism forbids cruelty to animals, flesh and egg were not allowed in the diet. The tender bamboo shoot (sǔn 筍 in Chinese) thus became a nutritious alternative. Preparation methods developed over thousands of years have come to be incorporated into Asian cuisines, especially for monks. A Buddhist monk, Zan Ning, wrote a manual of the bamboo shoot called Sǔn Pǔ (筍譜) offering descriptions and recipes for many kinds of bamboo shoots.[54] Bamboo shoot has always been a traditional dish on the Chinese dinner table, especially in southern China. In ancient times, those who could afford a big house with a yard would plant bamboo in their garden.

In Japan, a bamboo forest sometimes surrounds a Shinto shrine as part of a sacred barrier against evil. Many Buddhist temples also have bamboo groves.

Bamboo plays an important part of the culture of Vietnam. Bamboo symbolizes the spirit of Vovinam (a Vietnamese martial arts): cương nhu phối triển (coordination between hard and soft (martial arts)). Bamboo also symbolizes the Vietnamese hometown and Vietnamese soul: the gentlemanlike, straightforwardness, hard working, optimism, unity, and adaptability. A Vietnamese proverb says, "Tre già, măng mọc" (When the bamboo is old, the bamboo sprouts appear), the meaning being Vietnam will never be annihilated; if the previous generation dies, the children take their place. Therefore, the Vietnam nation and Vietnamese value will be maintained and developed eternally. Traditional Vietnamese villages are surrounded by thick bamboo hedges (lũy tre).

In mythology

Several Asian cultures, including that of the Andaman Islands, believe humanity emerged from a bamboo stem.

In Philippine mythology, one of the more famous creation accounts tells of the first man, Malakás ("Strong"), and the first woman, Maganda ("Beautiful"), each emerged from one half of a split bamboo stem on an island formed after the battle between Sky and Ocean. In Malaysia, a similar story includes a man who dreams of a beautiful woman while sleeping under a bamboo plant; he wakes up and breaks the bamboo stem, discovering the woman inside. The Japanese folktale "Tale of the Bamboo Cutter" (Taketori Monogatari) tells of a princess from the Moon emerging from a shining bamboo section. Hawaiian bamboo ('ohe) is a kinolau or body form of the Polynesian creator god Kāne.

A bamboo cane is also the weapon of Vietnamese legendary hero, Thánh Gióng, who had grown up immediately and magically since the age of three because of his wish to liberate his land from Ân invaders. An ancient Vietnamese legend (The Hundred-knot Bamboo Tree) tells of a poor, young farmer who fell in love with his landlord's beautiful daughter. The farmer asked the landlord for his daughter's hand in marriage, but the proud landlord would not allow her to be bound in marriage to a poor farmer. The landlord decided to foil the marriage with an impossible deal; the farmer must bring him a "bamboo tree of 100 nodes". But Gautama Buddha (Bụt) appeared to the farmer and told him that such a tree could be made from 100 nodes from several different trees. Bụt gave to him four magic words to attach the many nodes of bamboo: Khắc nhập, khắc xuất, which means "joined together immediately, fell apart immediately". The triumphant farmer returned to the landlord and demanded his daughter. Curious to see such a long bamboo, the landlord was magically joined to the bamboo when he touched it, as the young farmer said the first two magic words. The story ends with the happy marriage of the farmer and the landlord's daughter after the landlord agreed to the marriage and asked to be separated from the bamboo.

In a Chinese legend, the Emperor Yao gave two of his daughters to the future Emperor Shun as a test for his potential to rule. Shun passed the test of being able to run his household with the two emperor's daughters as wives, and thus Yao made Shun his successor, bypassing his unworthy son. After Shun's death, the tears of his two bereaved wives fell upon the bamboos growing there explains the origin of spotted bamboo. The two women later became goddesses Xiangshuishen after drowning themselves in the Xiang River.

See also

- Bamboo blossom

- Bamboo processing machine

- Bamboo torture

- Bambuseae

- Ceremonial pole

- Domesticated plants and animals of Austronesia

- International Network for Bamboo and Rattan

- List of bamboo species

- Mautam

- Plant textiles

- Table of Wood and Bamboo Mechanical and Agricultural Properties

- Xiangshuishen (Xiang River goddesses)

References

- Kelchner S; Bamboo Phylogeny Working Group (2013). "Higher level phylogenetic relationships within the bamboos (Poaceae: Bambusoideae) based on five plastid markers" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 67 (2): 404–413. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2013.02.005. ISSN 1055-7903. PMID 23454093. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2015.

- Soreng, Robert J.; Peterson, Paul M.; Romaschenko, Konstantin; Davidse, Gerrit; Zuloaga, Fernando O.; Judziewicz, Emmet J.; Filgueiras, Tarciso S.; Davis, Jerrold I.; Morrone, Osvaldo (2015). "A worldwide phylogenetic classification of the Poaceae (Gramineae)". Journal of Systematics and Evolution. 53 (2): 117–137. doi:10.1111/jse.12150. ISSN 1674-4918.

- Wilson, C.L. & Loomis, W.E. Botany (3rd ed.). Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Farrelly, David (1984). The Book of Bamboo. Sierra Club Books. ISBN 978-0-87156-825-0.

- "Fastest growing plant". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- Lakkad; Patel (June 1981). "Mechanical properties of bamboo, a natural composite". Fibre Science and Technology. 14 (4): 319–322. doi:10.1016/0015-0568(81)90023-3.

- Kaminski, S.; Lawrence, A.; Trujillo, D. (2016). "Structural use of bamboo. Part 1: Introduction to bamboo". The Structural Engineer. 94 (8): 40–43.

- Kaminski, S.; Lawrence, A.; Trujillo, D.; Feltham, I.; Felipe López, L. (2016). "Structural use of bamboo. Part 3: Design values". The Structural Engineer. 94 (12): 42–45.

- Grass Phylogeny Working Group II (2012). "New grass phylogeny resolves deep evolutionary relationships and discovers C4 origins". New Phytologist. 193 (2): 304–312. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03972.x. hdl:2262/73271. ISSN 0028-646X. PMID 22115274.

- Clark, LG; Zhang, W; Wendel, JF (1995). "A Phylogeny of the Grass Family (Poaceae) Based on ndhF Sequence Data". Systematic Botany. 20 (4): 436–460. doi:10.2307/2419803. JSTOR 2419803.

- Kitsteiner, John (13 January 2014). "Permaculture Plants: Bamboo". tcpermaculture.com. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- Newell, J (2004). "Chapter 11: Sakhalin Oblast" (PDF). The Russian Far East: A Reference Guide for Conservation and Development. McKinleyville, California: Daniel & Daniel. pp. 376, 384–386, 392, 404. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- Bystriakova, N.; Kapos, V.; Lysenko, I.; Stapleton, C. M. A. (September 2003). "Distribution and conservation status of forest bamboo biodiversity in the Asia-Pacific Region". Biodiversity and Conservation. 12 (9): 1833–1841. doi:10.1023/A:1024139813651.

- "Gorillas get drunk on bamboo sap". The Daily Telegraph. 23 March 2009. Archived from the original on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

- "Arundinaria gigantea (Walt.) Muhl. giant cane". PLANTS Database. USDA. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013.

- Huxley, Anthony; Griffiths, Mark; Levy, Margot, eds. (1992). New RHS Dictionary of Gardening. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-47494-5.

- "Bamboo Farming: An Opportunity To Transform Livelihoods". The New Times. 6 June 2010. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- McDill, Stephen. "MS Business Journal". MS Business Journal. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- Calderon, Cleofe E.; Soderstrom, Thomas R. (1979). "A Commentary on the Bamboos (Poaceae: Bambusoideae)". Biotropica. 11 (3): 161–172. doi:10.2307/2388036. JSTOR 2388036.

- Janzen, DH. (1976). "Why Bamboos Wait so Long to Flower". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 7: 347–391. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.07.110176.002023.

- Keeley, J.E.; Bond, W.J. (1999). "Mast flowering and semelparity in bamboos: The bamboo fire cycle hypothesis". American Naturalist. 154 (3): 383–391. doi:10.1086/303243. PMID 10506551.

- Saha, S.; Howe, H.F. (2001). "The Bamboo Fire Cycle Hypothesis: A Comment". The American Naturalist. 158 (6): 659–663. doi:10.1086/323593. PMID 18707360. S2CID 27091595.

- Keeley, J.E.; Bond, W.J. (2001). "On incorporating fire into our thinking about natural ecosystems: A response to Saha and Howe". American Naturalist. 158 (6): 664–670. doi:10.1086/323594. PMID 18707361.

- Veller, Carl; Nowak, Martin A.; Davis, Charles C. (2015). "Extended flowering intervals of bamboos evolved by discrete multiplication". Ecology Letters. 18 (7): 653–659. doi:10.1111/ele.12442. PMID 25963600.

- Zimmer, Carl (15 May 2015). "Bamboo Mathematicians". Phenomena: The Loom. National Geographic. Archived from the original on 30 March 2016.

- "Muli bamboo (plant) – Encyclopædia Britannica". Britannica.com. Archived from the original on 6 April 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- K.K. Seethalakshmi; M.S. Muktesh Kumar (1998). Bamboos of India – A Compendium. Kerala Forest Research Institute (KFRI) International. Archived from the original on 13 April 2015.

- Kitajima, T. (1986). "Contact allergy caused by bamboo shoots". Contact Dermatitis. 15 (2): 100–102. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1986.tb01293.x. PMID 3780197.

- Hipler U.-C.; et al. (1986). "Typ IV-Allergie gegen Bambusblätter - ein Fallbereicht" [Type IV allergy against bamboo leaves - a case study]. Allergo J. 14: 45.

- "Thinning bamboos, with itchy consequences". Succulents And More. 4 September 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- Razal, Ramon; Palijon, Armando (2009). Non-Wood Forest Products of the Philippines. Calamba City, Laguna: El Guapo Printing Press, Calamba Printing Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-971-579-058-1.

- Myers, Evan T. "Structural Bamboo Design in East Africa". Kansas State University. Archived from the original on 16 December 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2014. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "NYIS". Nyis.info. 24 October 2013. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- "In Fight Against Plastic Pollution, Sikkim Introduces Bamboo Water Bottles For Tourists". indiatimes.com. 1 March 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- "Article expired". 10 May 2013. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- "India's first biofuel refinery to harness fuel out of bamboo". 10 July 2016. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- Landler, Mark (27 March 2002). "Hong Kong Journal; For Raising Skyscrapers, Bamboo Does Nicely". New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 April 2009. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

- Nancy Moore Bess; Bibi Wein (1987). Bamboo in Japan. Kodansha International. p. 101. ISBN 978-4-7700-2510-4.

- Michelle Nijhuis (June 2009). "Bamboo Boom: Is This Material for You?". Scientific American Earth 3.0 Special. 19 (2): 60–65. doi:10.1038/scientificamericanearth0609-60.

- "\"Competition Bureau Takes Action to Ensure Accuracy for Textile Articles Labelled and Advertised as Bamboo\"". Competition Bureau Canada. 27 January 2010. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- "Four Companies Charged with Labeling Rayon Clothing As Bamboo". GreenBiz.com. 11 August 2009. Archived from the original on 13 August 2009. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

- Loewe, Michael (1997). "Wood and bamboo administrative documents of the Han period". In Edward L. Shaughnessy (ed.). New Sources of Early Chinese History. Society for the Study of Early China. pp. 161–192. ISBN 978-1-55729-058-8.

- Perdue, Robert E.; Kraebel, Charles J.; Tao Kiang (April 1961). "Bamboo Mechanical Pulp for Manufacture of Chinese Ceremonial Paper". Economic Botany. 15 (2): 161–164. doi:10.1007/BF02904089.

- Nanko, Hirko; Button, Allan; Hillman, Dave (2005). The World of Market Pulp. Appleton, WI, USA: WOMP, LLC. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-615-13013-2.

- Bhattacharya, S. (2010). Tropical Bamboo: Molecular profiling and genetic diversity study. Lambert Academic Publishing. ISBN 978-3-8383-7422-2.

- Brauen, M. Bamboo in Old Japan: Art and Culture on the Threshold to Modernity. The Hans Sporry Collection in the Ethnographic Museum of Zurich University. Arnoldsche Art Publishers: Stuttgart

- McCallum, T. M. Containing Beauty: Japanese Bamboo Flower Baskets. 1988. Museum of Cultural History, UCLA: Los Angeles

- Lee, Andy W.C.; Liu, Yihai (June 2003). "Selected physical properties of commercial bamboo flooring". Forest Products Journal. Madison. 53 (6): 23–26. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- Jen Lukenbill. "About My Planet: Bamboo Bikes". Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- Teo Kermeliotis (31 May 2012). "Made in Africa: Bamboo bikes put Zambian business on right track". CNN. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012.

- Bamboo: an untapped and amazing resource Archived 22 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine from UNIDO. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

- Chan, Alan Kam-leung and Gregory K. Clancey, Hui-Chieh Loy (2002). Historical Perspectives on East Asian Science, Technology and Medicine. Singapore: Singapore University Press. ISBN 9971-69-259-7. p. 15.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. p. 614.

- Laws, B. 2010. Bamboo. Fifty Plants that Changed the Course of History. New York:Firefly Books (U.S) Inc.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Bamboo |

| Wikispecies has information related to Bambusoideae |

- Bamboo Plants and Anatomy

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Bamboo Structural Design ISO Standards