Energy in Turkey

Turkey consumes over 6 exajoules of primary energy per year,[1] over 20 megawatt hours (MW/h) per person. 88% of energy is fossil fuels[2] and energy policy includes reducing fossil fuel imports, which are over 20% of import costs[3] and three quarters of the current account deficit.[4] Greenhouse gas emissions by Turkey are about 6 tons/person year,[5] which is more than the global average.[6]

| Economy of Turkey |

|---|

|

| Economic history of Turkey |

|

Stock exchange |

|

|

Since 1990 annual primary energy consumption has almost tripled to 1700 TW/h[note 1] in 2016; including 31% oil, 28% gas and 27% coal;[7] and CO2 emissions from fuel combustion have risen from 130 megatonnes (Mt) to 340 Mt.[8]

Although Turkey produces its own lignite (brown coal), the Sankey diagram of Turkey's energy balance shows that half the country's coal and almost all other fossil fuel is imported, and that renewables contribute little.[9] Three-quarters of energy is imported:[3] Turkey's energy policy prioritises reducing imports, but has been criticised by the OECD for lacking carbon pricing,[10] subsidizing fossil fuels[11] and not taking more advantage of the country's abundant wind and sunshine.[12]

The diagram of final consumption shows that most oil products are used for road transport and that homes and industry consume energy in various forms.[9] Electricity is generated mainly from coal, gas (about a third each) and hydro (about a quarter) with a small but growing amount from other renewables such as wind and solar.[13] A nuclear power plant is under construction.

Energy policy is to secure national energy supply[14] and reduce imports,[15] as in the 2010s fossil fuel costs were[16] a large part of Turkey's import bill.[17] This includes using energy efficiently. However, as of 2019, little research has been done on the policies Turkey uses to reduce energy poverty, which also include some subsidies for home heating and electricity use.[3] The energy strategy includes "within the context of sustainable development, giving due consideration to environmental concerns all along the energy chain".[15] Turkey's energy policy has been criticized for not looking much beyond 2023,[18] not sufficiently involving the private sector,[19] and for being inconsistent with Turkey's climate policy.[20]

Policy

Security of supply

Turkey meets a quarter of its energy demand from national resources.[21] But, as of 2019, the country is almost 40% fossil fuel energy dependant on Russia.[22] 99% of natural gas is imported and 93% of petroleum.[23] In the 2010s fossil fuel imports were probably the biggest structural vulnerability of the country's economy:[17] they cost $41 billion in 2019, about a fifth of the total import bill,[24] and were a large part of the 2018 current account deficit[25] and debt problems.

To secure energy supply the government is building new gas pipelines,[17] and diversifying energy sources. As of 2020 there is a surplus of electricity generation capacity,[26] however the government aims at meeting the forecast increase in demand for electricity in Turkey by building the first nuclear power plant in Turkey and more solar, wind, hydro and coal-fired power plants.[27] As an oil and gas importer Turkey can increase security of supply by increasing the proportion of renewable electricity.[21] The International Energy Agency has suggested that Turkey implement a carbon market.[28] In the long term a carbon tax would reduce import dependency by speeding development of national solar and wind energy.[29]

Because government in Turkey is very centralised energy policy is a national policy. However at certain times of year the east generates excess electricity as it has most hydroelectricity in Turkey, but far less industry and population than the west. This was part of the cause of the nationwide blackout in 2015 and therefore policy includes improving electricity transmission.[30] As well as natural gas storage and regasification plants,[31] the government supports pumped-storage hydroelectricity.[32]

Energy efficiency

Despite the Energy Efficiency Law and target to reduce energy intensity by at least 20 percent between 2011 and 2023; between 2005 and 2015 Turkey's energy intensity increased by 7 percent.[28] According to one study if energy policy was changed, most importantly to remove fossil fuel subsidies, at least 20% of energy could be saved in 2020.[33] Energy Minister Fatih Dönmez said in 2019 that improvement of public buildings should take the lead and that efficiency improvements are an important source of jobs.[34]

Fossil fuel subsidies and taxes

In the 21st century fossil fuel subsidies are around 0.2% of GDP,[35] including US$1.6 billion annually between 2015 and 2017.[36] The energy minister Fatih Dönmez supports coal[37][38] and most energy subsidies are to coal,[39] which has been strongly criticised by the OECD.[40] Capacity mechanism payments to coal-fired power stations in Turkey in 2019 totalled 720 million lira and to gas-fired power stations in Turkey 542 million lira.[41] As of 2018 the tax per unit energy on gasoline was higher than diesel,[42] despite diesel cars on average emitting more lung damaging NOx.[43] The price of residential gas and electricity is set by the government.[44]

Natural gas oligopoly

The purpose of the capacity market for electricity is claimed to be to secure supply: however despite almost all natural gas being imported some gas-fired power plants received capacity payments in 2019 whereas some non-fossil firm power such as demand response could not.[45] State-owned BOTAŞ controls 80% of the natural gas market and thus the price,[46] and due to the many sources of supply in the region and increasing liquefied natural gas imports[47][48] wholesale prices in USD are forecast to remain stable or decrease in the long-term.[49][50] However the wholesale gas market is not as competitive as in the EU, as Turkey does not want to split up BOTAŞ or give other power companies in Turkey fair use of BOTAŞ’ pipelines, so has not joined ENTSO-G.[28] Turkey's long-term contracts with all its current suppliers –Russia, Azerbaijan and Iran– are due to expire in the 2020s.[17] Exploration for gas in the Eastern Mediterranean is subsidized[51][39] and is a cause of geopolitical tension due to the Cyprus dispute.[52]

Coal subsidies

Coal in Turkey is heavily subsidized.[53] As of 2019 the government aims to keep the share of coal in the energy portfolio at around the same level in the medium to long term.[54] The place of coal in the government's energy policy was detailed in 2019 by the Foundation for Political, Economic and Social Research (SETA), Turkey's lobbying organisation.[55] Despite protests against coal power plants[56] Afşin-Elibistan C is being constructed by Turkey's state owned generator and Emba Hunutlu with Chinese finance.[57] Even in cities where natural gas is available the government supports poor households with free coal.[4]

Economics

As of 2018 for residential consumers ”high cost is the most important problem of Turkey’s energy system”.[58] Europe supports energy efficiency and renewable energy via the 1 billion euro Mid-size Sustainable Energy Financing Facility (MidSEFF).[28] Up to 150kWh per month free electricity is provided to 2 million poor families.[59] Fatih Birol, the head of the International Energy Agency said in 2019 that, because of its falling price, the focus should be on maximizing onshore wind power in Turkey.[60] The economics of coal power have been modelled[61] by Carbon Tracker and they calculate that by 2020, both new wind and solar power were cheaper than building new coal power plants; and they forecast that wind will become cheaper than existing coal plants in 2027, and solar in 2023.[62]

Import substitution

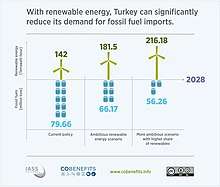

In 2017, a tenth of Turkey's electricity was generated by renewables, which reduced gas import costs. But being mainly hydroelectricity, this percentage is vulnerable to drought. According to Hülya Saygılı, an economist at Turkey's central bank, although imports of solar and wind power components accounted for 12 percent of import costs in 2017, in EU countries this is largely due to one-time setup costs. She said that compared with Italy and Greece, Turkey has not invested enough in solar and wind power.[63]

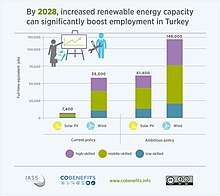

Potential employment co-benefits of a climate change policy

Increasing the share of renewable energy could make the country more energy independent and increase employment[64] especially in Turkey's solar PV and solar heating industries.[65]

Politics

Without subsidies new and some existing coal power would be unprofitable, and it is claimed that path dependence, political influence, and distorted markets are what is keeping it going.[66] Although the coal industry and the government are said to have a close relationship, economic downturn and the falling cost of wind and solar may increase pressure on coal subsidies.[67] Future import of gas from Northern Iraq may depend on relationships with the KRG, the central government of Iraq and Rosneft.[68] Hydroelectric plants, especially new ones, are sometimes controversial in local, international and environmental politics.[69] The EU might be able to persuade Turkey to cooperate on climate change by supporting policies that reduce the country's external energy dependency in a sustainable manner.[28]

State energy companies include: Eti Mine, Turkish Coal Enterprises, Turkish Hard Coal Enterprises, the Electricity Generation Company, BOTAŞ and TEİAŞ - the electricity trading and transmission company.[70] The government holds a quarter of total installed electricity supply and often offers prices below market levels.[71]

Energy transition

Nuclear safety regulations and human resources could be improved[72] by cooperation with Euratom.[28] In 2018 a new regulator was set up and $0.15 per kWh of generated electricity will be set aside for waste management.[73]

A plan for solar power in Turkey beyond 2023 is needed[74] and amending regulations on rooftop solar panels has been suggested to simplify installation on existing buildings and mandate for new buildings.[75]

In an attempt to reduce fossil fuel imports local production of electric cars and establishing solar cell factories is supported.[76]

Health and environment

Retrofitting equipment for pollution control such as flue-gas desulfurization, at old lignite-fuelled plants such as Soma,[77] might not be financially possible, as they use outdated technology.[78] Data on SO2, NOx and particulate air pollution from each large plant is collected by government[79] but not published.

The energy policy aim of reducing imports (e.g. of gas) conflicts with the climate change policy aim of reducing emission of greenhouse gases as some local resources (e.g. lignite) emit a lot of CO

2. According to Ümit Şahin, who teaches climate change at Sabancı University, Turkey must abandon fossil fuel completely and switch to 100% renewable energy by 2050.[80]

Energy sources

Coal

Coal supplies over a quarter of Turkey's primary energy.[81] The heavily subsidised coal industry generates over a third of the country's electricity[82] and emits a third of Turkey's greenhouse gases. Every year, thousands of people die prematurely from coal-related causes, the most common of which is local air pollution.

Most coal mined in Turkey is lignite (brown coal), which is more polluting than other types of coal.[83] Turkey's energy policy encourages mining lignite for coal-fired power stations in order to reduce gas imports;[82] and coal supplies over 40% of domestic energy production.[84] Mining peaked in 2018, at over 100 million tonnes,[85] and declined considerably in 2019.[86] In contrast to local lignite production, Turkey imports almost all of the bituminous coal it uses. The largest coalfield in Turkey is Elbistan.[87]Gas

Annual gas demand is about 50bcm,[88] over 30% of Turkey’s total energy demand, and over half of which is supplied by Russia.[17] As of 2019 storage capacity was 3.44 bcm and daily transmission capacity 318 mcm.[89] All 81 provinces in Turkey are supplied with natural gas,[90] which supplies most of the heat.[91] All industrial and commercial consumers and households buying over 75 thousand cubic-meters a year can switch suppliers.[4]

Gas from Russia comes via the Blue Stream and TurkStream pipelines (the other Russian pipeline via Ukraine is expected to stop supplying Turkey soon). Iran, the second biggest supplier, is connected via the Tabriz–Ankara pipeline.[92] Azerbaijan supplies Turkey through the South Caucasus Pipeline (which they claimed in 2018 was the cheapest that Turkey buys[93]): its gas flows onward through the Trans-Anatolian gas pipeline supplying Turkey and some continues across the Greek border into the Trans Adriatic Pipeline. Iraq may also supply gas in future, through the Southern Gas Corridor[94] and gas from the Eastern Mediterranean is also a possibility.[17]

About a quarter of the country's gas is imported as LNG,[95] which together with storage is important for meeting the winter demand peak.[17] Storage was 7.5% of annual demand in 2018 but being increased and a spot exchange was started in 2018.[4]

As of 2019 only a small proportion of gas imports are re-exported to the EU. However Turkey aims to become a gas trading hub[96] and re-export more.[88] 91 mt of CO2 were emitted by burning natural gas in 2015,[97] however subsidies to gas-fired power stations are being reduced in 2019 and 2020, so older less efficient plants may reduce generation.[98]

Long-term contracts with Russia, Iran and Azerbaijan will expire in the 2020s potentially allowing Turkey to negotiate lower prices.[99] Private companies are not allowed to make new pipeline gas contracts with countries that have contracts with state owned BOTAŞ, however they can contract for LNG.[4] As it has 80% of the market[100] BOTAŞ can and does subsidize residential and industrial customers.[4]

State-owned gas-fired power plants are less efficient than private sector ones but can outcompete them because the state guarantees a price for their electricity.[4]

Oil

Almost all oil is imported: mostly from Iraq, Russia and Kazakhstan[101][102] and oil also transits from Azerbaijan.[103] As most oil is used for transport it is hoped that electrifying land transport will reduce the import bill. Electric buses[104] and hybrid cars are manufactured locally,[105] and Turkey's automotive industry plans to make a national electric car from 2022.[106]

Nuclear

Turkey has no operational nuclear reactors, but it is building a nuclear power plant at Akkuyu, with expected operation in 2023. The nuclear power debate has a long history, with the 2018 construction start at Akkuyu being the sixth major attempt to build a nuclear power plant since 1960.[107]

Renewable energy

Hydroelectricity in Turkey is the largest renewable source of electricity and in 2018 was 9% of primary energy with other renewables at 6%.[108]

Geothermal power in Turkey is used mainly for heating. By massively increasing production of Turkey's solar power in the south and Turkey's wind power in the west the country's entire energy demand could be met from renewable sources.[109]

Electricity

303 billion kWh of electricity was used in Turkey in 2018,[110] which is almost a fifth of the amount of primary energy in Turkey. As the electricity sector in Turkey burns a lot of local and imported coal the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions by Turkey is the country's coal-fired power stations, many of which are subsidized. Imports of gas, mostly for power stations in Turkey, is the main import cost for the economy of Turkey. However solar power in Turkey and wind power in Turkey are being increased and balanced by the country's existing hydropower. Shura Energy Center has made many recommendations about electric vehicles.[111]

Conservation storage and transmission

According to the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, Turkey has the potential to cut 15 to 20 percent of total consumption through energy conservation.[112]

With the increase in electricity generated by solar panels storage may become more important. A pumped hydropower plant is planned to be completed by 2022.[113] Testing in Ankara suggested a payback time between 18 months and 3 years for adding ice thermal storage to hypermarket cooling systems.[114] Turkey could generate 20% of its total electricity from wind and solar by 2026 without extra transmission system costs.[115]

History

During the late 20th and early 21st centuries the country was very exposed to oil and gas price volatility.[116] However around the turn of the century many gas fired power plants were built, and BOTAŞ extended the national gas pipeline network to most of the urban population.[117] As Turkey has almost no natural gas of its own this increased import dependency, particularly on Russian gas.[118] Therefore many more regasification plants and gas storage (such as the gas storage at Lake Tuz) were built in the early 21st century, thus ensuring a much longer buffer should the main international import pipelines be cut for any reason. However growth in Turkish electricity demand has often been overestimated. Although much energy infrastructure was privatised in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, as of 2020, energy remained highly state controlled.[116]

Notes

- Production + imports - exports from top right of IEA table in the citation. 1 Mtoe = 11.63 TWh

References

- Turkstat report (2019), p. 71

- OECD (2019), section 1.

- Sonmez, Mustafa (2019-12-19). "Turkey's energy miscalculations have hefty cost". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 2019-12-21.

- "Energy pricing and non-market flows in Turkey's energy sector" (PDF). SHURA Energy Transition Center.

- "Turkey's greenhouse gas emissions up 4.4% in 2016". Anadolu.

- "Who emits more than their share of CO₂ emissions?".

- "Total Primary Energy Supply (TPES) by source:Turkey". IEA. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- "CO2 emissions Turkey". IEA. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- "General Directorate of Energy Affairs - Sankey Diagrams". eigm.gov.tr. Retrieved 2019-06-13.

- OECD (2019), page 117

- OECD (2019), pages 115,116

- OECD (2019), page 65

- "Electricity generation by fuel: Turkey". IEA. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- Öztürk, Sinan (2020-01-21). "Turkey Wealth Fund eyes becoming strategic investment arm of the country". Daily Sabah. Retrieved 2020-04-02.

- "TURKEY'S ENERGY PROFILE AND STRATEGY". Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Turkey). Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- "$2 gas in Europe is here: who will blink first?" (PDF).

- "Turkstream Impact on Turkey's Economy and Energy Security" (PDF). "Istanbul Economics" & "The Center for Economics and Foreign Policy" - EDAM. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- "How Turkey Can Ensure a Successful Energy Transition". Center for American Progress. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- "Turkey's foreign and security policy 'needs to support its energy goals'". Hürriyet. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- Turkey 2018 Report p92, European Commission, 17 April 2018

- "COBENEFITS". Retrieved 2020-03-11.

- "A cost-benefit analysis of Idlib for Turkey and Russia". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 2020-03-23.

- "COVID-19's blow to energy markets". www.aa.com.tr. Retrieved 2020-05-05.

- "Turkey's energy import bill falls more than 4% in 2019". Daily Sabah. 2020-02-06.

- "Coal Power Plants". Coal in Turkey. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- Europe Beyond Coal(2020), page 15

- BAYRAKTAR, ALPARSLAN (4 December 2018). "Analysis: Energy transition in Turkey". Hürriyet.

- "A NEW STRATEGY FOR EU-TURKEY ENERGY COOPERATION". Turkish Policy Quarterly. 27 November 2018.

- Bavbek, Gökşin. "Assessing the Potential Efects of a Carbon Tax in Turkey" (PDF). EDAM Energy and Climate Change Climate Action Paper Series 2016/6. p. 9. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- "EBRD to finance electricity distribution network expansion in Turkey". Power Technology | Energy News and Market Analysis. 2019-12-20. Retrieved 2020-03-12.

- "Number of licenses issued for gas exports from Turkey reaches 18". Daily Sabah. Anadolu Agency. 2020-02-11.

- "Turkey, China, US to build pumped-storage hydro plant". www.aa.com.tr. Retrieved 2020-04-13.

- Sever, S. Duygu. "Accelerating the Energy Transition in the Southern Mediterranean" (PDF).

- "Energy efficiency to raise savings in public sector". Daily Sabah. 2019-12-08.

- Acar, Sevil; Challe, Sarah; Christopoulos, Stamatios; Christo, Giovanna (2018). "Fossil fuel subsidies as a lose-lose: Fiscal and environmental burdens in Turkey". New Perspectives on Turkey. 58: 93–124. doi:10.1017/npt.2018.7.

- "Energy pricing and non-market flows in Turkey's energy sector" (PDF). SHURA Energy Transition Center.

- "Analysis: New Turkish energy minister bullish for coal -- but lira weakness limits market". S & P Global. 12 Jul 2018.

- "Court says 'environment report necessary' for planned coal mine in western Turkey". Demirören News Agency. 10 August 2018.

- "Fossil Fuel Support - TUR", OECD, accessed August 2018.

- "Taxing Energy Use 2019 : Using Taxes for Climate Action". OECD. Retrieved 2020-04-13.

- "Kapasite mekanizmasıyla 2019'da 40 santrale 1.6 milyar lira ödendi" (in Turkish). Enerji Günlüğü. 2020-02-06.

- "Taxing Energy Use 2019: Country Note – Turkey" (PDF). OECD.

- Leggett, Theo (2018-01-21). "Reality Check: Are diesel cars always the most harmful?". BBC News. Retrieved 2020-04-13.

- "Erdoğan announces discounts on residence electricity and natural gas prices ahead of Turkey's elections". Hürriyet Daily News. 25 December 2018.

- "ELEKTRİK PİYASASI KAPASİTE MEKANİZMASI YÖNETMELİĞİ," Resmî Gazete Issue:30307 Article 1 and Article 6 clause 2) h), 20 Jan 2018

- "Satış Fiyat Tarifesi | BOTAŞ - Boru Hatları İle Petrol Taşıma Anonim Şirketi". www.botas.gov.tr. Retrieved 2020-03-09.

- "The LNG moment: How US production could change more than just markets". Atlantic Council. 2019-04-16. Retrieved 2020-03-09.

- "Turkey offers opportunity for US LNG". www.petroleum-economist.com. Retrieved 2020-05-01.

- "Supply diversity, optimal prices lucrative for Turkey's energy demand". Daily Sabah. 12 March 2019.

- "Who Will Feed The LNG Monster?". Forbes. 6 February 2019.

- "Turkey to continue gas drilling work around Cyprus: Foreign minister". Anadolu Agency. 16 October 2018.

- Lawless, Ghislaine (2020-02-24). "What lies beneath: gas-pricing disputes and recent events in Southern Europe". Arbitration Blog. Retrieved 2020-03-09.

- Şahin (2018), p. 37

- Tech review 7th communication (2019), p. 20.

- "YERLİ VE MİLLİ ENERJİ POLİTİKALARI EKSENİNDE KÖMÜR" (PDF). SETAV. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- "Protest against coal power at Sirnak (Turkish)".

- "Emba Hunutlu coal power plant". Banktrack. Retrieved 2020-03-11.

- "Voters in Turkey keep energy policy in mind when voting: Survey". Hürriyet Daily News. 19 March 2019.

- "2 milyon 22 bin ailenin 80 liraya kadar elektrik faturasını devlet ödeyecek". Diken. 28 February 2019.

- sabah, daily (2019-12-30). "IEA head: Turkey could benefit from energy resource glut in upcoming period". Daily Sabah. Retrieved 2020-03-12.

- "GLOBAL COAL POWER ECONOMICS MODEL METHODOLOGY" (PDF).

- "WIND VS COAL POWER IN TURKEY/SOLAR PV VS COAL IN TURKEY" (PDF). Carbon Tracker. 2020.

- Saygılı, Hülya. "RENEWABLE ENERGY USE IN TURKEY". CBRT blog. Archived from the original on 18 February 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- Gomez et al: Future skills (2019), p. 2.

- "Renewable Energy and Jobs Annual Review 2018" (PDF). International Renewable Energy Agency. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- Roberts, David (2020-03-14). "4 astonishing signs of coal's declining economic viability". Vox. Retrieved 2020-03-21.

- Sencan, Gokce (2017). "Political Reasoning and Mechanisms behind Turkey's Coal-Intensive Energy Policy in the Era of Renewables". University of California, Santa Barbara. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.24500.86407.

- "TURKEY AND THE KURDISTAN REGION OF IRAQ: STRAINED ENERGY RELATIONS". Turkish Policy Quarterly. 27 November 2018.

- Eren, Ayşen (July 2018). "Transformation of the water-energy nexus in Turkey: Re-imagining hydroelectricity infrastructure". Energy Research & Social Science. 41: 22–31. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2018.04.013.

- "Turkey's state energy companies to invest $1.5B in 2019". Daily Sabah. 18 October 2018.

- Pamuk, Humeyra. "Once darling of foreign investors, Turkey's power market struggles". Reuters. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- "Managing the Risks of Nuclear Energy: The Turkish Case". Retrieved 2020-03-11.

- "Turkey sets up new nuclear regulator". Nuclear Engineering International. 13 July 2018.

- "Lessons from global experiences for accelerating energy transition in Turkey through solar and wind power" (PDF). Shura. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- Aşıcı (2017), page 44

- "Turkey to start local solar cell production on June 15". www.aa.com.tr. Retrieved 2020-04-13.

- "Our Continuing Investments". Konya Şeker. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- "Turkey's Compliance with the Industrial Emissions Directive" (PDF). tepav. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- Hatipoglu, Hakan. "Inventory of LCPs in Turkey LCP Database explained and explored" (PDF). Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- Şahin (2019), p. 30

- "Total primary energy supply (TPES) by source, Turkey". International Energy Agency. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- "Coal". Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources (Turkey). Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- "Lignite coal – health effects and recommendations from the health sector" (PDF). Health and Environment Alliance (HEAL). December 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 December 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- Ersoy (2019), p. 5

- "Turkey breaks local coal production record in 2018". Anadolu Agency. 16 January 2019. Archived from the original on 3 February 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- Di̇reskeneli̇, Haluk (3 January 2020). "Enerji piyasalarında 2020 yılı öngörüleri" [2020 energy market outlook]. Enerji Günlüğü (in Turkish).

- "Turkey transfers operating rights of seven coal fields to private companies". Hürriyet Daily News. 12 October 2018. Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- "From A Pipeline Nation To An Energy Trading Hub". Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- AA, Daily Sabah with (2020-01-05). "Total inflow to Turkish gas system down 6.33% in 2019". Daily Sabah. Retrieved 2020-03-27.

- "Natural Gas Distribution". Gazbir. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Turkey: Electricity and heat for 2016". IEA. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- Agency, Tasnim News (2020-03-31). "Blast Halts Iran's Gas Exports To Turkey". Eurasia Review. Retrieved 2020-04-02.

- "TANAP gas to provide cheapest among Turkey's imports". Daily Sabah. 30 May 2018.

- "Azerbaijan offers Iraq access to Europe gas pipelines". Agence France Presse.

- "Energy watchdog foresees 52.02 bcm gas consumption in 2020". DailySabah. Retrieved 2020-02-05.

- "EXIST To Open Spot Natural Gas Market At End Of Year".

- "CO2 emissions from fuel combustion" (PDF). International Energy Agency. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- "Outlook 2019: Turkish natural gas market set for potential 'de-liberalization' in 2019". Platts. S & P Global. 27 December 2018.

- Gas Supply Changes in Turkey (PDF). Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. 2018. p. 8.

- "Turkish households consumed cheapest natural gas in Europe in 2017". Daily Sabah. 12 August 2018.

- "Turkey's crude oil imports from Iran down by more than 70 pct in June". 19 August 2018.

- "Despite rhetoric, Turkey complies with U.S. oil sanctions on Iran". Reuters. 2019-05-21. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- "Turkish energy sector hit by lira depreciation: MUFG research". S & P Global. 7 August 2018.

- "Local bus manufacturers take stage at Busworld Europe fair". DailySabah. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- "Turkey determined to boost hybrid, electric car sales". Yeni Şafak. 29 January 2019. Archived from the original on 29 January 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- "Turkey plans to create domestic car with electric engine". Azernews. 23 March 2019. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- Aydın, Cem İskender (2020-01-01). "Nuclear energy debate in Turkey: Stakeholders, policy alternatives, and governance issues". Energy Policy. 136: 111041. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2019.111041. ISSN 0301-4215.

- BP (2019), p. 9

- Kilickaplan, Anil; Bogdanov, Dmitrii; Peker, Onur; Caldera, Upeksha; Aghahosseini, Arman; Breyer, Christian (2017-12-01). "An energy transition pathway for Turkey to achieve 100% renewable energy powered electricity, desalination and non-energetic industrial gas demand sectors by 2050". Solar Energy. 158: 218–235. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2017.09.030. ISSN 0038-092X.

- "The gross electricity consumption in Turkey in 2018 was 303,2 billion kWh". Turkey Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources. Retrieved 2019-09-11.

- Saygın et al (2019), pp. 77 onwards.

- "Turkey Promotes Energy Conservation". Archived from the original on 2014-03-08. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- "General Electric to make turbines for 1 GW pumped storage HPP in Turkey". Balkan Green Energy News. 2020-04-13. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- Erdemir, Dogan; Altuntop, Necdet (12 January 2018). "Effect of encapsulated ice thermal storage system on cooling cost for a hypermarket". International Journal of Energy Research. 42 (9): 3091–3101. doi:10.1002/er.3971.

- Shura2018, page 6

- "Turkey - Countries & Regions". IEA. Retrieved 2020-04-13.

- "BOTAŞ strategic plan 2015-2019" (PDF).

- Bauomy, Jasmin (2020-01-08). "Europe needs gas and Russia has it - the story behind the new pipeline". euronews. Retrieved 2020-03-12.

Sources

- 2019-2023 Strateji̇k Plani (PDF) (Report) (in Turkish). Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources (Turkey). May 2020.

- Aşıcı, Ahmet Atıl (May 2017). "Climate friendly Green Economy Policies" (PDF). Istanbul Policy Center.

- Şahin, Ümit (February 2018). "Carbon Lock-In in Turkey: A Comparative Perspective of Low-Carbon Transition with Germany and Poland" (PDF). Istanbul Policy Center.

- Sarı, Ayşe Ceren and Değer Saygın (2018). On the way to efficiently supplying more than half of Turkey's electricity from renewables: Opportunities to strengthen the YEKA auction model for enhancing the regulatory framework of Turkey´s power system transformation (PDF). SHURA Energy Transition Center. ISBN 978-605-2095-44-7.

- "Report on the technical review of the seventh national communication of Turkey" (PDF). UNFCCC. June 2019.

- Şahin, Ümit; Türkkan, Seçil (January 2019). "Turkey's Climate Policies Have Reached a Deadlock: It Takes Courage to Resolve It" (PDF). saha. Vol. Special Issue 2. pp. 24–30. ISSN 2149-7885.

- EÜAŞ - A briefing for investors, insurers and banks (PDF) (Report). Europe Beyond Coal. January 2020.

- Oecd (February 2019). "OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Turkey 2019". OECD. OECD Environmental Performance Reviews. doi:10.1787/9789264309753-en. ISBN 9789264309746.

- "Turkish Greenhouse Gas Inventory report". Turkish Statistical Institute (TurkStat report). April 2019.

- "BP Statistical Review of World Energy" (PDF). BP. 2019.

- Godron, Philipp and Mahmut Erkut Cebeci and Osman Bülent Tör and Değer Saygın (2018). Increasing the Share of Renewables in Turkey's Power System:Options for Transmission Expansion and Flexibility (PDF). SHURA Energy Transition Center. ISBN 978-605-2095-22-5.

- Saygın, Değer; Tör, Osman Bülent; Teimourzadeh, Saeed; Koç, Mehmet; Hildermeier, Julia; Kolokathis, Christos (December 2019). Transport sector transformation: Integrating electric vehicles into Turkey’s distribution grids (PDF). SHURA Energy Transition Center (Report).

External links

- Gas and electricity markets, generation and consumption up to date statistics

- Live carbon emissions from electricity generation

- "Alternatives to coal in Turkey" article Global Energy Monitor

- Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis

- Turkey Energy Transition Index 2019

- Energy Market Regulatory Authority

- Istanbul International Centre for Energy and Climate at Sabancı University

- Turkey International Energy Agency

- Electricity Market in Turkey and Administrative Sanctions (in Turkish)

- Global Fossil Infrastructure Tracker

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Energy in Turkey. |