Dobhashi

Dobhashi (Bengali: দোভাষী, romanized: Dōbhāṣī, Sylheti: ꠖꠥꠜꠣꠡꠤ, Dubhashi, Perso-Arab: دوبھاشی lit. 'bilingual'), was the Bengali language as its dialectal basis shifted to a highly Persianised variant. This style evolved in not only the Eastern Nagari script, but also in Sylheti Nagri as well as the Perso-Arabic script of Greater Chittagong and Arakan.[1] The dialect has had a major influence to the modern dialects of Eastern and Southeastern Bengal, such as Sylheti, Chittagonian and Rohingya.

| Dobhashi | |

|---|---|

| Region | Bengal, Arakan |

| Era | 14th-19th century |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

Name

Dobhashi means "bilingual" in Bengali and implies that it contained Persian (and Arabic which Persian borrowed many words from itself). Musalmani Bengali (Bengali: মুসলমানী বাংলা, romanized: Musolmani Bangla, Sylheti: ꠝꠥꠍꠟ꠆ꠝꠣꠘꠤ ꠛꠣꠋꠟꠣ, Perso-Arab: مسلمانی بانگلا) was coined later on in the nineteenth century by James Long, an Anglican priest. However, this term is considered incorrect as historically it has also been used by non-Muslim Bengalis as well.[2]

Characteristics

Dobhashi was a very versatile vernacular, and could grammatically change to adapt to Persian grammar, without sounding odd to the reader. Dobhashi was also used for forms of poetry and story-telling like Puthi, Kissa, Raag, Jari, Hamd, Na`at and Ghazal. Dobhashi writers were multilingual and multi-literate enabling them to study and engage with Persian, Arabic and Bengali literature.[3] Dobhashi manuscripts are paginated from right to left, imitating the Arabic alphabet-tradition.

The following is a sample text in Dobhashi Bengali of the Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the United Nations:

- তামাম ইনসান আজাদী ভাবে সমান ইজ্জত আর হক লইয়া পয়দা হয়। তাঁদের হুশ ও আকল আছে; অতএব একজন বেরাদরী মন লইয়া আরেক জনের সাথে ব্যবহার করা জরুরি আছে।

- Tamam insan azadi bhabe shoman izzot ar hok loiya poyda hoy. Tader hush o akol achhe; otoeb ekjon beradori mon loiya arek joner shathe bebohar kora zoruri achhe.

- All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

History

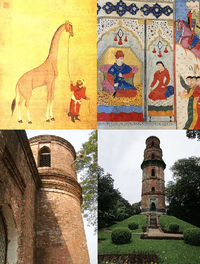

Dobhashi-style poetry (poetry using a mixed, off-Bengali language) is rarely produced today, but was in fact the most common linguistic form of writing in the Bengali language during the Sultanate and Mughal eras of Bengali history. Its heavy influence of Persian vocabulary is predominantly due to the latter being the official court language of the various Sultans and Emperors.The dialect is seen as the earliest emergence of Bengali Muslim literature, featuring Islamic terminology such as Allah, Rasul and Alim for the first time.[4]

The late 14th-century Sultan of Bengal, Ghiyathuddin Azam Shah, Turco-Persian in origin, was a patron of literature and poetry. His court poet, Shah Muhammad Saghir, a Bengali Muslim, was a pioneer in the emergence of Dobhashi literature. His works included Yusuf-Zulekha and he is considered to be the first Bengali Muslim and Dobhashi writer. 15th-century works included Zayn ad-Din's Rasul-bijoy, Syed Sultan's Shab-i-Miraj, Bahram Khan's Laily-Majnu, Dawlat Qazi Arakani's Chandrani Sati Maina.

There is a folk belief in the Sylhet region that a Muslim devised the Sylheti Nagri script for the purpose of mass Islamic education.[5] This is thought to happen during Bengal's 15th-century Hindu and Sanskrit reawakening led by Krishna Chaitanya.[6]

Bharatchandra Ray, referred to the language as "zabani misal", meaning a mixed language. He says:[7]

মানসিংহ পাতশায় হইল যে বাণী, উচিত যে আরবী পারসী হিন্দুস্থানী;

পড়িয়াছি সেই মত বৰ্ণিবারে পারি, কিন্তু সে সকল লোকে বুঝিবারে ভারি,

না রবে প্রসাদ গুণ না হবে রসাল, অতএব কহি ভাষা যাবনী মিশাল।

Mansingh Patshay hoilo je bani, uchit je Arobi, Parsi, Hindustani

Poriyachhi shei moto bornibare pari, kintu she shokol loke bujhibare bhari

Na robe prosad gun na hobe roshal, otoeb kohi bhasha zaboni mishal

This translates to: "The appropriate language for conversation between Mansingh and the Emperor are Arabic, Persian and Hindustani. I had studied these languages, and I could use them; but they are difficult for people to understand. They lack grace and juice (poetic quality). I have chosen, therefore, the mixed language".[8]

According to the 19th-century Chittagonian historian and Persian scholar, Hamidullah Khan, the contemporary 17th-century Arakanese poet Alaol borrowed many linguistic techniques and ideas from Persian literature. Alaol's works included Padmavati, Saif al-Mulk Badi uz-Zaman, Haft Paikar and Sikandarnama. Alaol gained recognition from other Arakanese poets such as Quraishi Magan Thakur.[3] There were many other 17th-century poets who were polyglot in a number of languages such as Abdul Hakim of Sandwip and Hayat Mahmud. Shah Faqir Gharibullah of Howrah was a very prominent Dobhashi writer who is said to have introduced its use in Western Bengal.

Medieval tales of Persian origin such as Gul-e-Bakavali were being translated to Dobhashi and being popularised in Bengal. Dobhashi puthis about the latter tale were written by the likes of Munshi Ebadat Ali in 1840. Muhammad Fasih was also a renowned Dobhashi puthi writer who was known to have written a 30-quatrain chautisa (poetic genre using all letters of the alphabet) using Arabic letters, totalling 120 lines.[9]

The famous Bangladeshi academic, Wakil Ahmed, states that Jaiguner Puthi (Puthi of Jaigun), written by Syed Hamzah of Udna, Hooghley in 1797, is "one of the finest examples" of puthis in Dobhashi. It took inspiration from earlier Bengali Muslim works such as Hanifar Digbijoy by Shah Barid Khan and Hanifar Lorai by Muhammad Khan (1724). Muhammad Khater was a late Dobhashi writer who wrote a puthi about ill-fated lovers in 1864, taking inspiration from the 16th century Bengali poet Dawlat Wazir Bahram Khan.[10]

The English Education Act 1835 banned the use of Persian and Arabic in education. Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, an employee of the East India Company, wrote books on Bengali language and considered the Perso-Arab vocabulary as pollutants and dismissed them from his works. Dobhashi is considered to have lost popularity as the Nadia variant of Bengali (inspired by the highly Sanskritised Shadhu-bhasha), became more institutionalised by the British, who worked alongside the educated Brahmins who chose to learn English, and created a standard (shuddho) form of Bengali. In reaction to Sanskritisation, educated Bengali Muslims, refusing to learn English, took to the initiative to revive Dobhashi literature hoping to maintain their identity and linguistic traditions. The dialect came to be known as Musalmani Bengali since then. In the mid-nineteenth century, printing houses in Calcutta and across Bengal, were producing hundreds and hundreds of Musalmani Bengali literature. In 1863, Nawab Abdul Latif founded the Mohammedan Literary Society.[11] The Christian Missionaries in Bengal also translated the Bible into what they called "Musalmani Bangla" in order for Bengali Muslims, that were uneducated in English and the standardised Bengali, to understand.

Nowadays, pure Dobhashi is mostly used for research purposes. Remants of the dialect is present in regional dialects of Bengali, in particular amongst rural Muslim communities. The Standard variant of Bengali used in Bangladesh contains somewhat more Perso-Arabic vocabulary compared to the Sanskritised standard used in West Bengal. The 20th century educationist and researcher, Dr Kazi Abdul Mannan (d. 1994), wrote his thesis on The Emergence and Development of Dobhasi Literature in Bengal (upto 1855 AD) for his PhD from Dhaka University in 1966.

See also

- Abdul Karim Sahitya Bisharad, historian who discovered hundreds of lost medieval literature and writers

- Bengali Kissa, popular genre found in Dobhashi literature

- Bengali poetry

- Puthi, popular genre found in Dobhashi literature

- Yusuf-Zulekha, an early Dobhashi work

References

- Muhammad Ashraful Islam (2012). "Bangladesh". In Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Mandal, Mousumi (17 March 2017). "Bonbibi-r Palagaan: Tradition, History and Performance". Sahapedia.

- d'Hubert, Thibaut (May 2014). In the Shade of the Golden Palace: Alaol and Middle Bengali Poetics in Arakan. ISBN 9780190860356.

- Wakil Ahmed (2012). "Persian". In Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Ahmad Hasan Dani (1958). "শ্রীহট্ট-নাগরী লিপির উৎপত্তি ও বিকাশ". Bangla Academy (in Bengali): 1.

- Islam, Muhammad Ashraful (2012). "Sylheti Nagri". In Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Bankim Chandra Chatterjee (1888). Bangadarshan (in Bengali). 2. p. 39.

- Dil, Afia (1972). The Hindu and Muslim Dialects of Bengali. Committee on Linguistics, Stanford University. p. 54.

- Wakil Ahmed (2012). "Chautisa". In Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Wakil Ahmed (2012). "Daulat Uzir Bahram Khan". In Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Amalendu De (1974). Roots of separatism in nineteenth century Bengal. Calcutta: Ratna Prakashan.