History of the taka

The history of the taka refers to the history of currency known as taka, tanka, tanga, tangka, tenge and tenga in many countries. The origin of the word is unclear. The currency is used in Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent. It was also used in Tibet (now part of China) and Arakan (now part of Myanmar).

| Numismatics |

|---|

.png) |

| Currency |

| Circulating currencies |

|

| Local currencies |

|

Fictional currencies Proposed currencies |

| History |

| Historical currencies |

| Byzantine |

| Medieval currencies |

| Production |

| Exonumia |

| Notaphily |

| Scripophily |

|

|

Etymology

The name of the tenga is derived from the Sanskrit word tanka.alternatively from a Turkic word Tamga or tamgha (Ottoman Turkish: طمغا, Old Turkic: 𐱃𐰢𐰍𐰀, Turkish: Damga), "stamp, seal". Many Turkic-speaking areas in Central Asia were once centers of Indo-Iranian languages.

South Asia

Word 'Tanka' is attested from Puri Kushan coins with brahmi script as (Nanaka Tanka) variously dated between 1st-7th century AD[1][2]

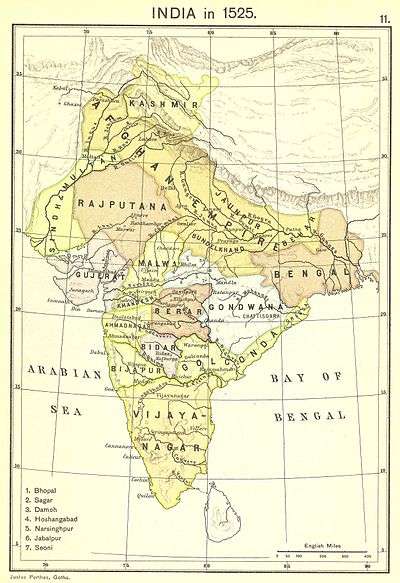

The imperial tanka was officially introduced by the monetary reforms of Muhammad bin Tughluq, the emperor of the Delhi Sultanate, in 1329. It was modeled as representative money, a concept pioneered as paper money by the Mongols in China and Persia. The tanka was minted in copper and brass. Its value was exchanged with gold and silver reserves in the imperial treasury. The currency was introduced due to the shortage of metals.[3] Over time, the tanka was minted in silver. However, chaos followed its launch in the 14th century, leading to the collapse of the Tughluq dynasty. The Tughluqs were succeeded by numerous regional states, including the Bengal Sultanate, the Jaunpur Sultanate, the Malwa Sultanate, the Berar Sultanate, the Sindh Sultanate, the Bidar Sultanate, the Ahmadnagar Sultanate, the Bahmani Sultanate and the Gujarat Sultanate. The new currency continued to be minted. In Berar in southern India, the tanka had a higher value than that of Delhi's tanka. Locals in many areas referred to currency as tanka even under Mughal rule.

Bengal became the stronghold of the tanka. The word tanka evolved into the Bengali word taka. Bengalis refer to any money as taka. The taka was the most important symbol of sovereignty for the Sultan of Bengal. The Sultanate of Bengal established at least 27 mints in provincial capitals across the kingdom.[4][5] The Bengali taka enjoyed a greater supply of silver than erstwhile Asian and European states.[6] In 1338, Ibn Battuta noticed that people in Bengal called their currency taka instead of dinar as was done in other Muslim kingdoms.[7] In 1415, Admiral Zheng He's fleet also saw the use of the silver taka in Bengal, according to the travelogue of Ma Huan.

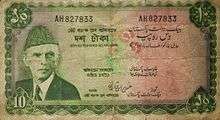

The tanka spread to Odisha on the west coast of the Bay of Bengal. Epigraphic records use terms such as vendi-tanka (alloyed silver) and sasukani-tanka (bullion).[8] To the north of Bengal, the tanka standard was adopted in prosperous Himalayan Kathmandu Valley in the 16th century as the coinage of Nepal. It was modeled on the currency of Delhi, Bengal and the Mughal Empire. The Nepalese tanka was a debased silver coin struck in 10 g. weight with minor denominations of 1⁄4, 1⁄32, 1⁄123, 1⁄512. It was introduced by King Indra Simha.[9] During the 20th century, when East Pakistan and West Pakistan were in a union, the Pakistani rupee had bilingual inscriptions using both Bengali script and Urdu sprit. The currency was called taka in East Pakistan and rupee in West Pakistan. After the independence of Bangladesh in 1971, the Bangladeshi taka became the official currency of Bangladesh. The Indian rupee is also colloquially called taka in the Indian state of West Bengal.

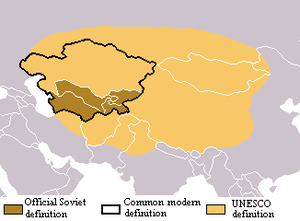

Central Asia

The term has been used for currency across Central Asia. The word is believed to have originated from the Turkic term Tamga, which meant seal or stamp. The Khwarazmi tenga was the currency of the Khwarazm region. In the Emirate of Bukhara, the currency was the Bukharan tenga. The Kokand tenga was the currency of the Khanate of Kokand. The Tanga was the currency of Tajkistan between 1995 and 2000.

The Kazakhstani tenge is the official currency of Kazakhstan.

.jpg)

East Asia

Tibet was located to the north of Bengal. The Tibetan tangka was an official currency of Tibet for three centuries. It was introduced by Lhasa Newar merchants from Nepal in the 16th century. The merchants used Nepalese tanka on the Silk Road. The Tibetan government began to mint the tangka in the 18th century. The first Tibetan tangka was minted in 1763/64. The Sino-Tibetan tangka carried Chinese language inscriptions.[10] Banknotes were issued between 1912 and 1941 in denominations of 5, 10, 15, 25 and 50 tangka.

On the northeastern coast of the Bay of Bengal, Arakan's Kingdom of Mrauk U minted coins modeled on the currency of the Bengal Sultanate.

Spread of the taka

The kingdoms which used the taka as currency were located along major trade routes, including the Silk Road, the Grand Trunk Road and Indian Ocean trade networks. Monetary customs spread across these areas as a result of the flow of merchants and commerce. The trade routes played an important role in the development of civilizations in Central and West Asia, China, the Himalayas, the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia and Africa.

References

- Congress, Indian History (2008). Proceedings. Indian History Congress.

- Chattopadhyay, Bhaskar (1967). A Numismatic Study.

- Shoaib Daniyal. "History revisited: How Tughlaq's currency change led to chaos in 14th century India". scroll.in. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- "Coins - Banglapedia". en.banglapedia.org. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- "Currency System - Banglapedia". en.banglapedia.org. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- John H Munro (6 October 2015). Money in the Pre-Industrial World: Bullion, Debasements and Coin Substitutes. Routledge. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-317-32191-0.

- Ian Blanchard (2005). Mining, Metallurgy and Minting in the Middle Ages: Continuing Afo-European supremacy, 1250-1450. Franz Steiner Verlag. p. 1264. ISBN 978-3-515-08704-9.

- Nihar Ranjan Patnaik (1997). Economic History of Orissa. Indus Publishing. p. 101. ISBN 978-81-7387-075-0.

- Joshi, Satya Mohan (1961). Nepali Rashtriya Mudra (National Coinage of Nepal). OCLC 652243631.

- Bertsch, Wolfgang: The Currency of Tibet. A Sourcebook for the Study of Tibetan Coins, Paper Money and other forms of Currency. Tibetan Works and Archives, Dharamsala, 2002.