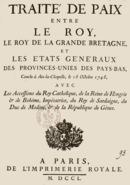

Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748)

The 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, sometimes called the Treaty of Aachen, ended the War of the Austrian Succession, following a congress assembled on 24 April 1748 at the Free Imperial City of Aachen.

Celebration of the Peace by Jacques Dumont | |

| Context | Ends the War of the Austrian Succession |

|---|---|

| Signed | 18 October 1748 |

| Location | Free Imperial City of Aachen, Holy Roman Empire |

| Effective | 18 October 1748 |

| Parties | |

A preliminary treaty setting out terms of the peace was agreed on 30 April 1748 by Britain, France, and the Dutch Republic, with a final version signed on 18 October. Austria, Spain, Sardinia, Modena, and Genoa later acceded to the Treaty in two separate agreements, on 4 December 1748 and 21 January 1749.

The Treaty largely failed to resolve the issues that caused the war, leading to the strategic realignment known as the Diplomatic Revolution, and the outbreak of the Seven Years' War in 1756.

Background

France and Britain began bilateral peace talks in August 1746 at Breda, but these were delayed by British hopes of improving their position in Flanders. Elsewhere, Austria made peace with Prussia in the December 1745 Treaty of Dresden, while by late 1746, their war with Spain in Northern Italy reached stalemate. Maria Theresa's husband Francis was made Holy Roman Emperor in September 1745 and her right to the Habsburg Monarchy recognised by the other claimants. Since the Austrian Netherlands were not considered a strategic possession, Maria Theresa had achieved her main war aims and wanted peace to restructure her administration and army, then regain Silesia.[1]

Despite victories in the Netherlands, throughout 1746 Finance Minister Machault repeatedly warned of the catastrophic state of French finances. The British naval blockade led to the collapse of customs receipts and severe shortages, especially among the poor, who relied upon Newfoundland cod as a cheap food source. After their losses at Cape Finisterre in October, the French navy could no longer protect their colonies or their trade routes.[2]

Under the British-Russian convention of November 1747, a Russian corps of 37,000 arrived in the Rhineland in February 1748; although they took Maastricht in May, the French position could only deteriorate. [3] However, lack of progress in Flanders and domestic opposition to the cost of subsidising its allies meant Britain was also ready to end the war; both France and Britain were prepared to impose terms on their allies if needed but preferred to avoid dropping them by making a separate peace treaty.[4]

To achieve this, France, Britain and the Dutch Republic signed a preliminary treaty on 30 April 1748, with conditions for a general peace, including the return of the Austrian Netherlands, the Dutch Barrier forts, Maastricht and Bergen op Zoom. They also guaranteed the Austrian cession of Silesia to Prussia, as well as the Duchies of Parma, Piacenza, and Guastalla to Philip of Spain (1720–1765). Faced with the threat of continuing the war on their own, Austria, Sardinia, Spain, and Genoa acceded to the treaty on 4 December 1748 and 21 January 1749.[5]

Terms

These included the following;

(1) Austria recognises the Prussian acquisition of Silesia and cedes the Duchies of Parma, Piacenza and Guastalla to Philip of Spain (1720–1765), eldest son of Philip V of Spain and Elisabeth Farnese;

(2) France withdraws from the Austrian Netherlands and returns the Dutch Barrier Forts, Maastricht and Bergen op Zoom;

(3) Britain returns the French possession of Louisbourg in Nova Scotia for Madras, captured by France in 1746;

(4) Austria withdraws from the Duchy of Modena and Republic of Genoa;

(5) Renewal of the Asiento slavery contract, granted to Britain by Spain in the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht; Britain renounced this under the 1750 Treaty of Madrid, in return for £10,000;

(6) A commission is established to resolve competing claims between French and British colonists in North America.

Aftermath

The Treaty largely restored the position prior to the outbreak of war in 1740 but failed to resolve the commercial issues that caused it. Few Frenchmen understood the desperate financial state that required the return of their gains in the Austrian Netherlands; combined with the lack of tangible benefits for helping Prussia, it led to the phrase "as stupid as the Peace".[6]

A commission to negotiate competing territorial claims in North America was set up, but made very little progress. Britain exchanged the French stronghold of Louisbourg, in Novia Scotia for Madras, much to the fury of British colonists. Many saw the peace terms as driven by the interests of George II's German possession of Hanover, rather than Britain. Attempts to build public support for the dynasty led to a spectacular fireworks display in Green Park, for which Handel composed his Music for the Royal Fireworks. Neither of the two main protagonists appeared to have gained much for their investment and both viewed the Treaty as an armistice, not a peace.[7]

In Austria, reactions were mixed; Maria Theresa was determined to regain Silesia and resented British support for Prussia's occupation.[8] On the other hand, the Treaty confirmed her right to the Monarchy, while the Habsburgs survived a potentially disastrous crisis, regained the Austrian Netherlands without fighting and made minor concessions in Italy.[9] Administrative and financial reforms made it stronger in 1750 than 1740, while its strategic position was strengthened through installing Habsburgs as rulers of key territories in Northwest Germany, the Rhineland and Northern Italy.[10]

Of the other combatants, Spain retained its predominance in Spanish America and made minor gains in Northern Italy. With French support, Prussia doubled in size with the acquisition of Silesia but twice made peace without informing their ally; Louis XV already disliked Frederick and now viewed him as untrustworthy. The war exposed the weakness of the Dutch Barrier forts, which had proved unable to stand up to modern artillery and confirmed their decline as a Great Power. Combined with the feeling they received little value for their subsidies, this led Britain to align with Prussia, rather than Austria, to protect Hanover from French aggression.[11]

These factors led to the realignment known as the 1756 Diplomatic Revolution and the 1756 to 1763 Seven Years' War, which was even grander in scale than its predecessor.

References

- Scott 2015, pp. 58-60.

- Black 1999, pp. 97-100.

- Hochedlinger 2003, pp. 259.

- Scott 2015, p. 61.

- Lesaffer, Randall. "The Peace of Aachen (1748) and the Rise of Multilateral Treaties". Oxford Public International Law. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- McLynn 2008, p. 1.

- McLynn 2008, p. 2.

- McGill 1971, p. 229.

- Armour 2012, pp. 99-101.

- Black 1994, p. 63.

- Browning 1975, p. 150.

Sources

- Armour, Ian (2012). A History of Eastern Europe 1740–1918. Bloomsbury Academic Press. ISBN 978-1849664882.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Black, Jeremy (1999). Britain as a Military Power, 1688-1815. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-85728-772-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Browning, Reed (1993). The War of the Austrian Succession. New York: St Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-09483-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hochedlinger, Michael (2003). Austria's Wars of Emergence, 1683-1797. Routledge. ISBN 978-0582290846.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McGill, William J (1971). "The Roots of Policy: Kaunitz in Vienna and Versailles, 1749-1753". The Journal of Modern History. 43 (2): 228–244. doi:10.1086/240615. JSTOR 1876544.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McLynn, Frank (2008). 1759: The Year Britain Became Master of the World. Vintage. ISBN 978-0099526391.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Olson, J.S.; Shadle, R. Historical Dictionary of the British Empire. Greenwood Press. (1996): 1095-1099. ISBN 9780313293672.

- Savelle, Max. "Diplomatic Preliminaries of the Seven Years' War in America". Canadian Historical Review. Vol. 20, No. 1 (1939): 17. doi:10.3138/CHR-020-01-04.

- Scott, Hamish (2015). The Birth of a Great Power System, 1740-1815. Routledge. ISBN 978-1138134232.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sosin, Jack M., "Louisburg and the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle, 1748," The William and Mary Quarterly. Third Series, Vol. 14, No. 4 (Oct. 1957): 516–535

External links

- Lesaffer, Randall. "The Peace of Aachen (1748) and the Rise of Multilateral Treaties". Oxford Public International Law. Retrieved 14 September 2019.