Climate change in Tuvalu

Global warming (recent climate change) is dangerous in Tuvalu since the average height of the islands is less than 2 metres (6.6 ft) above sea level, with the highest point of Niulakita being about 4.6 metres (15 ft) above sea level. Tuvalu islands have increased in size between 1971 and 2014, during a period of global warming.[1] Over 4 decades, there had been a net increase in land area in Tuvalu of 73.5 ha (2.9%), although the changes are not uniform, with 74% increasing and 27% decreasing in size. The sea level at the Funafuti tide gauge has risen at 3.9 mm per year, which is approximately twice the global average.[2]

.svg.png)

Tuvalu could be one of the first nations to experience the effects of sea levels raised.[3] Not only could parts of the island be flooded but the rising saltwater table could also destroy deep rooted food crops such as coconut, pulaka, and taro.[4][5] Research from the University of Auckland suggests that Tuvalu may remain habitable over the next century, but as of March 2018 Enele Sopoaga, the prime minister of Tuvalu, stated that Tuvalu is not expanding and has gained no additional habitable land.[6][7]

Enele Sopoaga, has also said that evacuating the islands is the last resort.[8]

Climate systems that affect Tuvalu

Tuvalu participates in the operations of the Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP).[9] The climate of the Pacific region at the equator is influenced by a number of factors; the science of which is the subject of continuing research. The SPREP described the climate of Tuvalu as being:

[I]nfluenced by a number of factors such as trade wind regimes, the paired Hadley cells and Walker circulation, seasonally varying convergence zones such as the South Pacific Convergence Zone (SPCZ), semi-permanent subtropical high-pressure belts, and zonal westerlies to the south, with the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) as the dominant mode of year to year variability (…). The Madden–Julian oscillation (MJO) also is a major mode of variability of the tropical atmosphere-ocean system of the Pacific on times scales of 30 to 70 days (…), while the leading mode with decadal time-scale is the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO) (…). A number of studies suggest the influence of global warming could be a major factor in accentuating the current climate regimes and the changes from normal that come with ENSO events (…).[10]

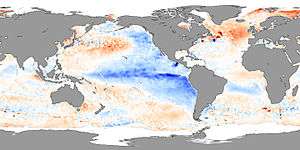

The sea level in Tuvalu varies as a consequence of a wide range of atmospheric and oceanographic influences.[11] The 2011 report of the Pacific Climate Change Science Program published by the Australian Government,[12] describes a strong zonal (east‑to-west) sea-level slope along the equator, with sea level west of the International Date Line (180° longitude) being about a half metre higher than found in the eastern equatorial Pacific and South American coastal regions. The trade winds that push surface water westward create this zonal tilting of sea level on the equator. Below the equator a higher sea level can also be found about 20° to 40° south (Tuvalu is spread out from 6° to 10° south).[13]

The Pacific Climate Change Science Program Report (2011) describes the year-by-year volatility in the sea-level as resulting from the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO):

ENSO has a major influence on sea levels across the Pacific and this can influence the occurrence of extreme sea levels. During La Niña events, strengthened trade winds cause higher than normal sea levels in the western tropical Pacific, and lower than normal levels in the east. Conversely, during El Niño events, weakened trade winds are unable to maintain the normal gradient of sea level across the tropical Pacific, leading to a drop in sea level in the west and a rise in the east. Pacific islands within about 10° of the equator are most strongly affected by ENSO‑related sea-level variations.[13]

The Pacific (inter-)decadal oscillation is a climate switch phenomenon that results in changes from periods of La Niña to periods of El Niño. This has an effect on sea levels as El Niño events can actually result in sea levels falling by 11 inches (28.4 centimeters) as compared to the sea level during a La Niña events.[14] For example, in 2000 there was a switch from periods of downward pressure of El Niño on sea levels to an upward pressure of La Niña on sea levels, which upward pressure causes more frequent and higher high tide levels. The Perigean spring tide (often called a king tide) can result in seawater flooding low-lying areas of the islands of Tuvalu.[15]

Measuring climate change effects in Tuvalu

In 1978 a tide gauge was installed at Funafuti by the University of Hawaii.[6] However, the uncertainty as to the accuracy of the data from this tide gauge resulted in a modern Aquatrak acoustic gauge being installed in 1993 by the Australian National Tidal Facility (NTF) as part of the AusAID-sponsored South Pacific Sea Level and Climate Monitoring Project.[16]

The highest elevation is 4.6 metres (15 ft) above sea level on Niulakita,[17] which gives Tuvalu the second-lowest maximum elevation of any country (after the Maldives). However, the highest elevations are typically in narrow storm dunes on the ocean side of the islands which are prone to over topping in tropical cyclones, such as occurred with Cyclone Bebe.[18] In March 2015 the storm surge created by Cyclone Pam resulted in waves of 3 to 5 metres (9.8 to 16.4 ft) breaking over the reef of the outer islands caused damage to houses, crops and infrastructure.[19][20] On Nui the sources of fresh water were destroyed or contaminated.[21][22]

Tuvalu is also affected by perigean spring tide events (often called a king tide), which raise the sea level higher than a normal high tide.[23] The highest peak tide recorded by the Tuvalu Meteorological Service was 3.4 metres (11 ft) on 24 February 2006 and again on 19 February 2015.[24][25] As a result of historical sea level rise, the king tide events lead to flooding of low-lying areas, which is compounded when sea levels are further raised by La Niña effects or local storms and waves.[15] In the future, sea level rise may threaten to submerge the nation entirely as it is estimated that a sea level rise of 20–40 centimetres (7.9–15.7 inches) in the next 100 years could make Tuvalu uninhabitable.[26][27]

The atolls have shown resilience to gradual sea-level rise, with atolls and reef islands being able to grow under current climate conditions by generating sufficient sand and broken coral that accumulates and gets dumped on the islands during cyclones.[28][29][30] There remains the risk that the dynamic response of atolls and reef islands does not result in stable islands as tropical cyclones can strip the low-lying islands of their vegetation and soil. Tepuka Vili Vili islet of Funafuti atoll was devastated by Cyclone Meli in 1979, with all its vegetation and most of its sand swept away during the cyclone.[31] Vasafua islet, part of the Funafuti Conservation Area, was severely damaged by Cyclone Pam in 2015. The coconut palms were washed away, leaving the islet as a sand bar.[32][33] The effect of Cyclone Pam, which did not pass directly over the islands, shows that Tuvaluans are exposed to storm surges causing damage to their houses and crops, and also the risk of water born disease as a consequence of contamination of the water supplies.[19][34][35]

Gradual sea-level rise also allows for coral polyp activity to raise the atolls with the sea level. However, if the increase in sea level occurs at faster rate as compared to coral growth, or if polyp activity is damaged by ocean acidification, then the resilience of the atolls and reef islands is less certain.[36]

There is further contention as to whether saltwater encroachment that is destroying the gardens for pulaka, taro and coconut palms is the consequence of changes in the sea level;[37] or the consequence of the fresh water being extracted from the freshwater lens in the sub-surface of the atoll or the consequence of the creation of the borrow pits, which are the result of the extraction of coral to build the runway at Funafuti during World War II.[14] The investigation of groundwater dynamics of Fongafale Islet, Funafuti, show that tidal forcing results in salt water contamination of the surficial aquifer during spring tides.[38] The degree of aquifer salinization depends on the specific topographic characteristics and the hydrologic controls in the sub-surface of the atoll. About half of Fongafale islet is reclaimed swamp that contains porous, highly permeable coral blocks that allow the tidal forcing of salt water.[39] Increases in the sea level will exacerbate the aquifer salinization as the result of increases in tidal forcing.

Concerns over long term habitability

Existing scientific narratives suggest that Tuvalu may become uninhabitable as a consequence of rising sea levels, however results of research from the University of Auckland challenge the existing narratives by showing that island expansion has been the most common physical alteration throughout Tuvalu over the past four decades. The results challenge the existing perceptions of island loss due to rising sea levels by showing that the islands are dynamic features that will persist as sites for habitation over the next century and allows for alternate opportunities for adaptation rather than a forced exodus.[6]

Despite these findings the Prime Minister of Tuvalu maintains that "Tuvalu [is] not expanding" and that "the expansion of Tuvaluan shoreline did not equate to habitable land."[7]

Estimates as to changes in the sea level relative to the islands of Tuvalu

The Permanent Service for Mean Sea Level (PSMSL) analysis of data from Funafuti is that the sea level has risen at 3.9 mm per year, which is approximately twice the global average.[2] Sea level observation has been made at two at locations within the Funafuti lagoon. The University of Hawai’i Sea Level Center (UHSLC) operated a tide gauge from November 1979 until December 2001. Since June 1993 the National Tidal Centre of the Australian Bureau of Meteorology has operated an Aquatrak acoustic gauge. The two records were synthesised into a single data source by averaging the difference between the two records over the period during which both gauges operated simultaneously.[2]

There are observable changes that have occurred over the last ten to fifteen years that show Tuvaluans that there have been changes to sea levels.[40] Those observable changes include sea water bubbling up through the porous coral rock to form pools on each high tide and flooding of low-lying areas including the airport on a regular basis during spring tides and king tides.[41][42][43]

2011 report of the Pacific Climate Change Science Program

The 2011 report of the "Pacific Climate Change Science Program"[44] of Australian concludes in relation to Tuvalu that over the course of the 21st century:

• Surface air temperature and sea‑surface temperature are projected to continue to increase (very high confidence).[44]

• Annual and seasonal mean rainfall is projected to increase (high confidence).[44]

• The intensity and frequency of days of extreme heat are projected to increase (very high confidence).[44]

• The intensity and frequency of days of extreme rainfall are projected to increase (high confidence).[44]

• The incidence of drought is projected to decrease (moderate confidence).[44]

• Tropical cyclone numbers are projected to decline in the south-east Pacific Ocean basin (0–40ºS, 170ºE–130ºW) (moderate confidence).[44]

• Ocean acidification is projected to continue (very high confidence).[44]

• Mean sea-level rise is projected to continue (very high confidence).[44]

National response to the challenges faced by Tuvalu

Tuvalu faces challenges which will be exacerbated by climate change, those challenges are:

i) Coastal erosion, saltwater intrusion and increasing vector and water borne diseases due to sea level rise;

ii) Inadequate potable water due to less rainfall and prolonged droughts;

iii) Pulaka pit salinisation due to saltwater intrusion; and

iv) Decreasing fisheries population.[45]

The National Advisory Council on Climate Change

In a speech on 16 September 2005 to the 60th Session of the UN General Assembly, Prime Minister Maatia Toafa emphasized the impact of climate change as a "broader security issue which relates to environmental security. Living in a very fragile island environment, our long-term security and sustainable development is closely linked to issues of climate change, preserving biodiversity, managing our limited forests and water resources."[46]

The threat of climate change to the islands is not a dominant motivation for migration as Tuvaluans appear to prefer to continue living in Tuvalu for reasons of lifestyle, culture and identity.[47][48] In 2013 Enele Sopoaga, the prime minister of Tuvalu, said that relocating Tuvaluans to avoid the impact of sea level rise "should never be an option because it is self defeating in itself. For Tuvalu I think we really need to mobilise public opinion in the Pacific as well as in the [rest of] world to really talk to their lawmakers to please have some sort of moral obligation and things like that to do the right thing."[49]

‘The Economics of Climate Change in the Pacific’ 2013 report of the Asian Development Bank estimates the range of potential economic impacts of climate change for agriculture, fisheries, tourism, coral reefs, and human health in the Pacific region; with agriculture production, such as taro, particularly vulnerable to the effect of climate change.[50] The Pacific countries are projected incur economic losses in the range of 4.6% to 12.7% of the region's annual GDP equivalent by 2100, with the degree of severity changing with different CO2 emission scenarios. [50]

On 16 January 2014 Prime Minister Enele Sopoaga established the National Advisory Council on Climate Change, which functions are "to identify actions or strategies: to achieve energy efficiencies; to increase the use of renewable energy; to encourage the private sector and NGOs to reduce greenhouse gas emissions; to ensure a whole of government response to adaptation and climate change related disaster risk reduction; and to encourage the private sector and NGOs to develop locally appropriate technologies for adaptation and climate change mitigation (reductions in [greenhouse gas])."[51]

At the 20th Conference of Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change in December 2014 at Lima, Peru, Sopoaga said "Climate change is the single greatest challenge facing my country. It is threatening the livelihood, security and wellbeing of all Tuvaluans."[52]

Te Kakeega III - National Strategy for Sustainable Development-2016-2020 (TK III) sets out the development agenda of the Government of Tuvalu. TK III includes new strategic areas, in addition to the eight identified in TK II. The additional strategic areas are climate change; environment; migration and urbanization; and oceans and seas.[53]

Tuvalu's role at the Copenhagen Climate Change Conference 2009

In December 2009 the islands stalled talks at United Nations Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen, fearing some other developing countries were not committing fully to binding deals on a reduction in carbon emission, their chief negotiator stated "Tuvalu is one of the most vulnerable countries in the world to climate change, and our future rests on the outcome of this meeting."[54] When the conference failed to reach a binding, meaningful agreement, Tuvalu's representative Ian Fry said, "It looks like we are being offered 30 pieces of silver to betray our people and our future... Our future is not for sale. I regret to inform you that Tuvalu cannot accept this document."[55]

Fry's speech to the conference was a highly impassioned plea for countries around the world to address the issues of man-made global warming resulting in climate change. The five-minute speech addressed the dangers of rising sea levels to Tuvalu and the world. In his speech Fry claimed man-made global warming to be currently "the greatest threat to humanity", and ended with an emotional "the fate of my country rests in your hands".[56]

Climate change leadership and the Majuro Declaration 2013

In November 2011, Tuvalu was one of the eight founding members of Polynesian Leaders Group, a regional grouping intended to cooperate on a variety of issues including culture and language, education, responses to climate change, and trade and investment.[57] Tuvalu participates in the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), which is a coalition of small island and low-lying coastal countries that have concerns about their vulnerability to the adverse effects of global climate change. The Sopoaga Ministry led by Enele Sopoaga made a commitment under the Majuro Declaration, which was signed on 5 September 2013, to implement power generation of 100% renewable energy (between 2013 and 2020). This commitment is proposed to be implemented using Solar PV (95% of demand) and biodiesel (5% of demand). The feasibility of wind power generation will be considered.[58]

Marshall Islands President Christopher Loeak presented the Majuro Declaration to the UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon during General Assembly Leaders’ week from 23 September 2013. The Majuro Declaration is offered as a "Pacific gift" to the UN Secretary-General in order to catalyze more ambitious climate action by world leaders beyond that achieved at the December 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP15). On 29 September 2013 the Deputy Prime Minister Vete Sakaio concluded his speech to the General Debate of the 68th Session of the United Nations General Assembly with an appeal to the world, "please save Tuvalu against climate change. Save Tuvalu in order to save yourself, the world".[59]

2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP21) and the Paris Agreement

Commitment under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) 1994

On 27 November 2015 the Government of Tuvalu announced its intended Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) in relation to the reduction of greenhouse gases (GHGs) under provisions of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which became effective on 21 March 1994:

Tuvalu commits to reduction of emissions of green-house gases from the electricity generation (power) sector, by 100%, ie almost zero emissions by 2025.[60]

Tuvalu’s indicative quantified economy-wide target for a reduction in total emissions of GHGs from the entire energy sector to 60% below 2010 levels by 2025.[60]

These emissions will be further reduced from the other key sectors, agriculture and waste, conditional upon the necessary technology and finance.[60]

These targets go beyond the targets enunciated in Tuvalu’s National Energy Policy (NEP) and the Majuro Declaration on Climate Leadership (2013). Currently, 50% of electricity is derived from renewables, mainly solar, and this figure will rise to 75% by 2020 and 100% by 2025. This would mean almost zero use of fossil fuel for power generation. This is also in line with our ambition to keep the warming to less than 1.5⁰C, if there is a chance to save atoll nations like Tuvalu.[60]

Tuvalu's COP21 goal of global temperature below 1.5 degrees Celsius relative to pre-industrial levels

Prime Minister Enele Sopoaga said at the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP21) that the goal for COP21 should a global temperature goal of below 1.5 degrees Celsius relative to pre-industrial levels, which is the position of the Alliance of Small Island States.[61][62] Ms. Pepetua Latasi, the director of the Department of Environment, was the Chief Negotiator for Tuvalu.[63] Prime Minister Sopoaga said in his speech to the meeting of heads of state and government:

Tuvalu’s future at current warming, is already bleak, any further temperature increase will spell the total demise of Tuvalu…. For Small Island Developing States, Least Developed Countries and many others, setting a global temperature goal of below 1.5 degrees Celsius relative to pre-industrial levels is critical. I call on the people of Europe to think carefully about their obsession with 2 degrees. Surely, we must aim for the best future we can deliver and not a weak compromise.[64]

The countries participating in the Paris Agreement agreed to reduce their carbon output "as soon as possible" and to do their best to keep global warming "to well below 2 degrees C".[65] Enele Sopoaga described the important outcomes of the Paris Agreement as including the stand-alone provision for assistance to small island states and some of the least developed countries for loss and damage resulting from climate change and the ambition of limiting temperature rise to 1.5 degrees by the end of the century.[66]

Tuvalu Survival Fund (TSF)

The Tuvaluan government established the Tuvalu Survival Fund (TSF) in 2016 to finance climate change programs and as a fund available to respond promptly to natural disasters, such as tropical cyclones.[67] Contributions are made to the TSF from the national budget.[67][68]

The National Adaptation Programme of Action and the Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project

Tuvalu's National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA) describes a response to the climate change problem as using the combined efforts of several local bodies on each island that will work with the local community leaders (the Falekaupule). The main office, named the Department of Environment, is responsible for coordinating the non-governmental organizations, religious bodies, and stakeholders. Each of the named groups are responsible for implementing Tuvalu's NAPA, the main plan to adapt to the adverse effects of human use and climate change.[69]

In 2015 the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) assisted the government of Tuvalu to acquire MV Talamoana, a 30-metre vessel that will be used to implement Tuvalu's National Adaptation Programme of Action to transport government officials and project personnel to the outer islands.[70]

In August 2017 the Government of Tuvalu along and the UNDP launched the Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project (TCAP) that is financed with US$36 million from the Green Climate Fund and T$2.9 million from the Government of Tuvalu. The TCAP focuses on construction works to defend infrastructure including roads, schools, hospitals and government buildings.[71][72] over a period of seven years.[73][67] The goal of the Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project is to build coastal resilience in three of Tuvalu's nine inhabited islands and to manage coastal inundation risks by reducing the impact of increasingly intensive wave action.[67]

See also

Filmography

Documentary films about climate change and Tuvalu:

- Paradise Domain – Tuvalu (Director: Joost De Haas, Bullfrog Films/TVE 2001) 25:52 minutes - YouTube video.[74]

- Tuvalu island tales (A Tale of two Islands) (Director: Michel Lippitsch) 34 minutes - YouTube video

- The Disappearing of Tuvalu: Trouble in Paradise (2004) by Christopher Horner and Gilliane Le Gallic.[75]

- Paradise Drowned: Tuvalu, the Disappearing Nation (2004) Written and produced by Wayne Tourell. Directed by Mike O'Connor, Savana Jones-Middleton and Wayne Tourell.[76]

- Going Under (2004) by Franny Armstrong, Spanner Films.[74]

- Before the Flood: Tuvalu (2005) by Paul Lindsay (Storyville/BBC Four).[74]

- Time and Tide (2005) by Julie Bayer and Josh Salzman, Wavecrest Films.[77]

- Tuvalu: That Sinking Feeling (2005) by Elizabeth Pollock from PBS Rough Cut

- Atlantis Approaching (2006) by Elizabeth Pollock, Blue Marble Productions [78]

- King Tide | The Sinking of Tuvalu (2007) by Juriaan Booij.[79]

- Tuvalu (Director: Aaron Smith, ‘Hungry Beast’ program, ABC June 2011) 6:40 minutes - YouTube video.

- Tuvalu: Renewable Energy in the Pacific Islands Series (2012) a production of the Global Environment Facility (GEF), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and SPREP 10 minutes – YouTube video.

- ThuleTuvalu (2014) by Matthias von Gunten, HesseGreutert Film/OdysseyFilm.[80]

References

- Kench, Paul S; Ford, Murray R; Owen, Susan D (2018). "'Sinking' Pacific nation is getting bigger: study". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 605. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9..605K. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-02954-1. PMC 5807422. PMID 29426825.

A University of Auckland study examined changes in the geography of Tuvalu's nine atolls and 101 reef islands between 1971 and 2014, using aerial photographs and satellite imagery

- Supplementary note 2 in Kench, Paul S; Ford, Murray R; Owen, Susan D (2018). "Patterns of island change and persistence offer alternate adaptation pathways for atoll nations". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 605. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9..605K. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-02954-1. PMC 5807422. PMID 29426825.

- "Tuvalu's Views on the Possible Security Implications of Climate Change to be included in the report of the UN Secretary General to the UN General Assembly 64th Session" (PDF). Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Tuvalu could lose root crop". Radio New Zealand. 17 September 2008. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- "Leaflet No. 1 - Revised 1992 - Taro". Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- Kench, Paul S; Ford, Murray R; Owen, Susan D (2018). "Patterns of island change and persistence offer alternate adaptation pathways for atoll nations". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 605. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9..605K. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-02954-1. PMC 5807422. PMID 29426825.

- "TUVALU PM REFUTES AUT RESEARCH". 2018-03-19. Retrieved 2019-03-26.

- Eleanor Ainge Roy (17 May 2019). "'One day we'll disappear': Tuvalu's sinking islands". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- "SPREP". Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Program. 2009. Retrieved 22 Oct 2011.

- "Pacific Adaptation to Climate Change Tuvalu Report of In-Country Consultations" (PDF). Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Program (SPREP). 2009. Retrieved 13 Oct 2011.

- "Current and Future Climate of Tuvalu" (PDF). Tuvalu Meteorological Service, Australian Bureau of Meteorology & Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- "Climate Change in the Pacific: Scientific Assessment and New Research". Pacific Climate Change Science Program (Australian Government). November 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Ch.2 Climate of the Western Tropical Pacific and East Timor" (PDF). Climate Change in the Pacific: Volume 1: Regional Overview. Australia Government: Pacific Climate Change Science Program. 2011. p. 26.

- Field, Michael (28 March 2002). "Global Warming Not Sinking Tuvalu - But Maybe Its Own People Are". Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 13 Oct 2011.

- Packard, Aaron (12 March 2015). "The Unfolding Crisis in Kiribati and the Urgency of Response". HuffPostGreen. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- Hunter, John R. (2002). "A Note on Relative Sea Level Change at Funafuti, Tuvalu" (PDF). Antarctic Cooperative Research Centre. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- Lewis, James (December 1989). "Sea level rise: Some implications for Tuvalu". The Environmentalist. 9 (4): 269–275. doi:10.1007/BF02241827.

- Bureau of Meteorology (1975) Tropical Cyclones in the Northern Australian Regions 1971-1972 Australian Government Publishing Service

- Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) Tuvalu: Tropical Cyclone Pam (PDF). International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (Report). ReliefWeb. 16 March 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- "One Tuvalu island evacuated after flooding from Pam". Radio New Zealand International. 18 March 2015. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "Flooding in Vanuatu, Kiribati and Tuvalu as Cyclone Pam strengthens". SBS Australia. 13 March 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- "State of emergency in Tuvalu". Radio New Zealand International. 14 March 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- Shukman, David (22 January 2008). "Tuvalu struggles to hold back tide". BBC News. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- "Tuvalu surveys road damage after king tides". Radio New Zealand. February 24, 2015. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- "Peak tide affects Tuvaluan communities living in coastal and low-lying areas" (PDF). Island Business (FENUI NEWS/PACNEWS). 24 February 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- Patel, S. S. (2006). "A sinking feeling". Nature. 440 (7085): 734–736. Bibcode:2006Natur.440..734P. doi:10.1038/440734a. PMID 16598226.

- Hunter, J. A. (2002). Note on Relative Sea Level Change at Funafuti, Tuvalu Archived 2011-10-07 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 13 May 2006.

- Kench, Paul. "Dynamic atolls give hope that Pacific Islands can defy sea rise". The Conversation. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- Arthur P. Webba; Paul S. Kench (2010). "The dynamic response of reef islands to sea-level rise: Evidence from multi-decadal analysis of island change in the Central Pacific". Global and Planetary Change. 72 (3): 234–246. Bibcode:2010GPC....72..234W. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2010.05.003.

- Warne, Kennedy (13 February 2015). "Will Pacific Island Nations Disappear as Seas Rise? Maybe Not - Reef islands can grow and change shape as sediments shift, studies show". National Geographic. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- "Kogatapu Funafuti Conservation Area". Tuvaluislands.com. Retrieved 28 Oct 2011.

- Wilson, David (4 July 2015). "Vasafua Islet vanishes". Tuvalu-odyssey.net. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- Endou, Shuuichi (28 March 2015). "バサフア島、消失・・・(Vasafua Islet vanishes)". Tuvalu Overview (Japanese). Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- "Tuvalu: Tropical Cyclone Pam Situation Report No. 1 (as of 22 March 2015)". Relief Web. 22 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Tuvalu: Tropical Cyclone Pam Situation Report No. 2 (as of 30 March 2015)". Relief Web. 30 March 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- Kench, Paul. "Dynamic atolls give hope that Pacific Islands can defy sea rise (Comments)". The Conversation. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- Baarsch, Florent (4 March 2011). "Warming oceans and human waste hit Tuvalu's sustainable way of life". The Guardian. London.

- Nakada S.; Yamano H.; Umezawa Y.; Fujita M.; Watanabe M.; Taniguchi M. (2010). "Evaluation of Aquifer Salinization in the Atoll Islands by Using Electrical Resistivity". Journal of the Remote Sensing Society of Japan. 30 (5) Journal of the Remote Sensing Society of Japan. 30: 317–330. doi:10.11440/rssj.30.317.

- Nakada, S.; Umezawa, Y.; Taniguchi, M.; Yamano, H. (2012). "Groundwater Dynamics of Fongafale Islet, Funafuti Atoll, Tuvalu". Ground Water. 50 (4): 639–644. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6584.2011.00874.x. PMID 22035506.

- Laafai, Monise (October 2005). "Funafuti King Tides". Retrieved 14 Oct 2011.

- Mason, Moya K. "Tuvalu: Flooding, Global Warming, and Media Coverage". Retrieved 13 Oct 2011.

- Dekker, Rodney (9 December 2011). "Island neighbours at the mercy of rising tides". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 9 Dec 2011.

- Holowaty Krales, Amelia (20 February 2011). "Chasing the Tides, parts I & II". Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- "Ch.15 Tuvalu". Climate Change in the Pacific: Volume 2: Country Reports. Australia Government: Pacific Climate Change Science Program. 2011.

- "Tuvalu's National Adaptation Programme of Action - Under the auspices of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change" (PDF). Ministry of Natural Resources, Environment, Agriculture and Lands - Department of Environment. May 2007. Retrieved 24 Oct 2011.

- "2005 World Summit - 60th Session of the UN General Assembly" (PDF). UN. 16 September 2005. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- Corlew, Laura (2012). "The cultural impacts of climate change: sense of place and sense of community in Tuvalu, a country threatened by sea level rise" (PDF). Ph D dissertation, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- Colette Mortreux; Jon Barnett (2009). "Climate change, migration and adaptation in Funafuti, Tuvalu". Global Environmental Change. 19: 105–112. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.09.006.

- "Relocation for climate change victims is no answer, says Tuvalu PM". Radio New Zealand International. 3 September 2013. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- Xianbin Yao; Cyn-Young Park (November 2013). "The Economics of Climate Change in the Pacific". Asian Development Bank. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- "Pacific Adaptation To Climate Change: Tuvalu - Report Of In-Country Consultations" (PDF). SPREP. 2015. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- Sopoaga, Enele (December 2014). "Speech at the 20th Conference of Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change" (PDF). Government of Tuvalu. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- "Te Kakeega III - National Strategy for Sustainable Development-2016-2020" (PDF). Government of Tuvalu. 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- "Island's tough climate plea denied". BBC News. 2009-12-09. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- Future not for sale: climate deal rejected

- YouTube video of Fry's speech, accessed 2011-03-10

- "NZ may be invited to join proposed ‘Polynesian Triangle’ ginger group", Pacific Scoop, 19 September 2011

- "Majuro Declaration: For Climate Leadership". Pacific Islands Forum. 5 September 2013. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- "Statement Presented by Deputy Prime Minister Honourable Vete Palakua Sakaio". 68th Session of the United Nations General Assembly - General Debate. 28 September 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- "Intended Nationally Determined Contributions Communicated to the UNFCCC" (PDF). Government of Tuvalu. 27 November 2015. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- Sims, Alexandra (2 December 2015). "Pacific Island Tuvalu calls for 1.5 degrees global warming limit or faces 'total demise'". The Independent. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- Paul, Stella (11 December 2015). "Honour Our Right to Exist, Say Pacific Island Leaders at COP21". Inter Press Service. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- "Tuvalu Chair of UN Loss and Damage Committee". SPREP. 5 December 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- Sopoaga, Enele S. (30 November 2015). "Keynote statement delivered by the Prime Minister of Tuvalu, the Honourable Enele S. Sopoaga, at the leaders events for heads of state and government at the opening of the COP21" (PDF). Government of Tuvalu. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- "Adoption of the Paris agreement—Proposal by the President—Draft decision -/CP.21" (PDF). UNFCCC. 2015-12-12. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Tuvalu PM praises COP 21 agreement". Radio New Zealand International. 16 December 2015. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- "Tuvalu: 2018 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for Tuvalu". International Monetary Fund Country Report No. 18/209. 5 July 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- "Government of Tuvalu 2017 National Budget" (PDF). Presented by the Hon Maatia Toafa Minister for Finance and Economic Development. 30 November 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- "Tuvalu's National Adaptation Programme of Action" (PDF). Department of Environment of Tuvalu. May 2007. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- "UNDP Supports Tuvalu Ship". Fiji Sun Online. 15 January 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- "Tuvalu's climate resilience shored up with launch of US$38.9 million adaptation project". UN Development Programme. 30 August 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- "Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project". Government of Tuvalu. June 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- "PROJECT FP015 Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project". Green Climate Fund. June 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- Mason, Moya K. (2017). "Tuvalu: Flooding, Global Warming, and Media Coverage". Moya K. Mason. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- "DER Documentary: The Disappearing of Tuvalu: Trouble in Paradise". DER Documentary. 2004. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- "Documentary: Paradise Drowned". NZ Geographic. 2004. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- "Time and Tide". Wavecrest Films. 2005. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- "Atlantis Approaching: The Movie". Blue Marble Productions. 2006. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- "King Tide - The Sinking of Tuvalu". Juriaan Booij. 2007. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- "ThuleTuvalu". HesseGreutert Film/OdysseyFilm. 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

External links

- Te Kakeega III - National Strategy for Sustainable Development-2016-2020

- Talofa! Tuvalu Met Service

- South Pacific Sea Level and Climate Monitoring Project (SPSLCMP)

- Island Climate Update, (NIWA) National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research of New Zealand

- Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Program

- Talanoa Dialogue Portal (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC))

- Tuvalu's options on setting up defences against the rising sea

- The cultural impacts of climate change (2012) Ph D dissertation, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa by Laura Kati Corlew

- Small Is Beautiful A lobby group set up to help the island nation

- News

- Climate Change - Tuvalu - ACF Newsource

- Environment: Tiny Tuvalu Fights for Its Literal Survival IPS News

- Video

- (28 Sep 2013) Address by His Excellency Vete Palakua Sakaio, Deputy Prime Minister of Tuvalu at the general debate of the 68th Session of the General Assembly of the United Nations

- King Tide - Funafuti (Storm Video 2005) - YouTube video

- 1024 #90 King Tide Attacks in Tuvalu (TITV Weekly) - YouTube video

Further reading

- Corlew, Laura Kati. The cultural impacts of climate change : sense of place and sense of community in Tuvalu, a country threatened by sea level change. Middletown, DE. ISBN 9781479282487. OCLC 908251867.