Cinema of Italy

The Cinema of Italy comprises the films made within Italy or by Italian directors. The first Italian director is considered to be Vittorio Calcina, a collaborator of the Lumière Brothers, who filmed Pope Leo XIII in 1896. Since its beginning, Italian cinema has influenced film movements worldwide. As of 2018, Italian films have won 14 Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film (the most of any country) as well as 12 Palmes d'Or (the second-most of any country), one Academy Award for Best Picture and many Golden Lions and Golden Bears.

| Cinema of Italy | |

|---|---|

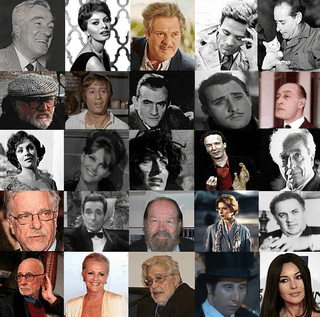

A collage of notable Italian actors and filmmakers[lower-alpha 1] | |

| No. of screens | 3,217 (2013)[1] |

| • Per capita | 5.9 per 100,000 (2013)[1] |

| Main distributors | Medusa Film (16.7%) Warner Bros. (13.8%) 20th Century Fox (13.7%)[2] |

| Produced feature films (2013)[3] | |

| Total | 167 |

| Number of admissions (2013)[3] | |

| Total | 97,380,572 |

| • Per capita | 1.50 (2012)[4] |

| National films | 30,208,422 (31.0%) |

| Gross box office (2013)[3] | |

| Total | €618 million |

| National films | €188 million (30.5%) |

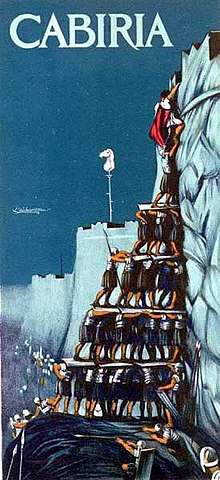

Italy is a birthplace of Art Cinema and the stylistic aspect of film has been the most important factor in the history of Italian movies.[5][6] In the early 1900s, artistic and epic films such as Otello (1906), The Last Days of Pompeii (1908), L'Inferno (1911), Quo Vadis (1913), and Cabiria (1914), were made as adaptations of books or stage plays. Italian filmmakers were utilizing complex set designs, lavish costumes, and record budgets, to produce pioneering films. One of the first cinematic avante-garde movements, Italian Futurism, took place in Italy in the late 1910s. After a period of decline in the 1920s, the Italian film industry was revitalized in the 1930s with the arrival of sound film. A popular Italian genre during this period, the Telefoni Bianchi, consisted of comedies with glamorous backgrounds.[7]

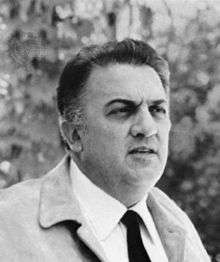

While Italy's Fascist government provided financial support for the nation's film industry, most notably the construction of the Cinecittà studios (the largest film studio in Europe), it also engaged in censorship, and thus many Italian films produced in the late 1930s were propaganda films. Post-World War II Italy saw the rise of the influential Italian neorealist movement, which launched the directorial careers of Luchino Visconti, Roberto Rossellini, and Vittorio De Sica. Neorealism declined in the late 1950s in favor of lighter films, such as those of the Commedia all'italiana genre and important directors like Federico Fellini and Michelangelo Antonioni. Actresses such as Sophia Loren, Giulietta Masina and Gina Lollobrigida achieved international stardom during this period.[7]

The Spaghetti Western achieved popularity in the mid-1960s, peaking with Sergio Leone's Dollars Trilogy, which featured enigmatic scores by composer Ennio Morricone, which have become popular culture icons of the Western genre. Erotic Italian thrillers, or giallos, produced by directors such as Mario Bava and Dario Argento in the 1970s, influenced the horror genre worldwide. During the 1980s and 1990s, directors such as Ermanno Olmi, Bernardo Bertolucci, Giuseppe Tornatore, Gabriele Salvatores and Roberto Benigni brought critical acclaim back to Italian cinema.[7]

The country is also famed for its prestigious Venice Film Festival, the oldest film festival in the world, held annually since 1932 and awarding the Golden Lion.[8] In 2008 the Venice Days ("Giornate degli Autori"), a section held in parallel to the Venice Film Festival, has produced in collaboration with Cinecittà studios and the Ministry of Cultural Heritage a list of 100 films that have changed the collective memory of the country between 1942 and 1978: the "100 Italian films to be saved".

History

Early years

The French Lumière brothers commenced public screenings in Italy in 1896: in March 1896, in Rome and Milan; in April in Naples, Salerno and Bari; in June in Livorno; in August in Bergamo, Bologna and Ravenna; in October in Ancona;[9] and in December in Turin, Pescara and Reggio Calabria. Lumière trainees produced short films documenting everyday life and comic strips in the late 1890s and early 1900s. Pioneering Italian cinematographer Filoteo Alberini patented his "Kinetograph" during this period.[7]

The Italian film industry took shape between 1903 and 1908, led by three major organizations: Cines, based in Rome; and the Turin-based companies Ambrosio Film and Itala Film. Other companies soon followed in Milan and Naples, and these early companies quickly attained a respectable production quality and were able to market their products both within Italy and abroad.

Early Italian films typically consisted of adaptations of books or stage plays, such as Mario Caserini's Otello (1906) and Arturo Ambrosio's 1908 adaptation of the novel, The Last Days of Pompeii. Also popular during this period were films about historical figures, such as Caserini's Beatrice Cenci (1909) and Ugo Falena's Lucrezia Borgia (1910). L'Inferno, produced by Milano Films in 1911, was the first full-length Italian feature film ever made.[10] Popular early Italian actors included Emilio Ghione, Alberto Collo, Bartolomeo Pagano, Amleto Novelli, Lyda Borelli, Ida Carloni Talli, Lidia Quaranta and Maria Jacobini.[7]

Enrico Guazzone's 1913 film Quo Vadis was one of the earliest "blockbusters" in cinema history, utilizing thousands of extras and a lavish set design. Giovanni Pastrone's 1914 film Cabiria was an even larger production, requiring two years and a record budget to produce, and it was the first epic film ever made. Nino Martoglio's Lost in Darkness, also produced in 1914, documented life in the slums of Naples, and is considered a precursor to the Neorealist movement of the 1940s and 1950s.[7]

Between 1911 and 1919, Italy was home to the first avant-garde movement in cinema, inspired by the country's Futurism movement. The 1916 Manifesto of Futuristic Cinematography was signed by Filippo Marinetti, Armando Ginna, Bruno Corra, Giacomo Balla and others. To the Futurists, cinema was an ideal art form, being a fresh medium, and able to be manipulated by speed, special effects and editing. Most of the futuristic-themed films of this period have been lost, but critics cite Thaïs (1917) by Anton Giulio Bragaglia as one of the most influential, serving as the main inspiration for German Expressionist cinema in the following decade.

The Italian film industry struggled against rising foreign competition in the years following World War I.[7] Several major studios, among them Cines and Ambrosio, formed the Unione Cinematografica Italiana to coordinate a national strategy for film production. This effort was largely unsuccessful, however, due to a wide disconnect between production and exhibition (some movies weren't released until several years after they were produced).[11] Among the notable Italian films of the late silent era were Mario Camerini's Rotaio (1929) and Alessandro Blasetti's Sun (1929).[7]

Cinecittà

In 1930, Gennaro Righelli directed the first Italian talking picture, The Song of Love. This was followed by Blasetti's Mother Earth (1930) and Resurrection (1931), and Camerini's Figaro and His Great Day (1931). The advent of talkies led to stricter censorship by the Fascist government.[7]

During the 1930s, light comedies known as telefoni bianchi ("white telephones") were predominant in Italian cinema.[7] These films, which featured lavish set designs, promoted conservative values and respect for authority, and thus typically avoided the scrutiny of government censors. Important examples of telefoni bianchi include Guido Brignone's Paradiso (1932), Carlo Bragaglia's O la borsa o la vita (1933), and Righelli's Together in the Dark (1935). Historical films such as Blasetti's 1860 (1934) and Carmine Gallone's Scipio Africanus: The Defeat of Hannibal (1937) were also popular during this period.[7]

In 1934, the Italian government created the General Directorate for Cinema (Direzione Generale per le Cinematografia), and appointed Luigi Freddi its director. With the approval of Benito Mussolini, this directorate called for the establishment of a town southeast of Rome devoted exclusively to cinema, dubbed the Cinecittà ("Cinema City"). Completed in 1937, the Cinecittà provided everything necessary for filmmaking: theaters, technical services, and even a cinematography school, the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, for younger apprentices. The Cinecittà studios were Europe's most advanced production facilities, and greatly boosted the technical quality of Italian films.[7] Many films are still shot entirely in Cinecittà.

During this period, Mussolini's son, Vittorio, created a national production company and organized the work of noted authors, directors and actors (including even some political opponents), thereby creating an interesting communication network among them, which produced several noted friendships and stimulated cultural interaction.

Neorealism

By the end of World War II, the Italian "neorealist" movement had begun to take shape. Neorealist films typically dealt with the working class (in contrast to the Telefoni Bianchi), and were shot on location. Many neorealist films, but not all, utilized non-professional actors. Though the term "neorealism" was used for the first time to describe Luchino Visconti’s 1943 film, Ossessione, there were several important precursors to the movement, most notably Camerini's What Scoundrels Men Are! (1932), which was the first Italian film shot entirely on location, and Blasetti's 1942 film, Four Steps in the Clouds.[12]

Ossessione angered Fascist officials. Upon viewing the film, Vittorio Mussolini is reported to have shouted, "This is not Italy!" before walking out of the theater.[13] The film was subsequently banned in the Fascist-controlled parts of Italy. While neorealism exploded after the war, and was incredibly influential at the international level, neorealist films made up only a small percentage of Italian films produced during this period, as postwar Italian moviegoers preferred escapist comedies starring actors such as Totò and Alberto Sordi.[12]

Neorealist works such as Roberto Rossellini's trilogy Rome, Open City (1945), Paisà (1946), and Germany, Year Zero (1948), with professional actors such as Anna Magnani and a number of non-professional actors, attempted to describe the difficult economic and moral conditions of postwar Italy and the changes in public mentality in everyday life. Visconti's The Earth Trembles (1948) was shot on location in a Sicilian fishing village, and utilized local non-professional actors. Giuseppe De Santis, on other hand, used actors such as Silvana Mangano and Vittorio Gassman in his 1949 film, Bitter Rice, which is set in the Po Valley during rice-harvesting season.

Poetry and cruelty of life were harmonically combined in the works that Vittorio De Sica wrote and directed together with screenwriter Cesare Zavattini: among them, Shoeshine (1946), The Bicycle Thief (1948) and Miracle in Milan (1951). The 1952 film Umberto D. showed a poor old man with his little dog, who must beg for alms against his dignity in the loneliness of the new society. This work is perhaps De Sica's masterpiece and one of the most important works in Italian cinema. It was not a commercial success and since then it has been shown on Italian television only a few times. Yet it is perhaps the most violent attack, in the apparent quietness of the action, against the rules of the new economy, the new mentality, the new values, and it embodies both a conservative and a progressive view.

Although Umberto D. is considered the end of the neorealist period, later films such as Federico Fellini's La Strada (1954) and De Sica's 1960 film Two Women (for which Sophia Loren won the Oscar for Best Actress) are grouped with the genre. Director Pier Paolo Pasolini's first film, Accattone (1961), shows a strong neorealist influence.[12] Italian neorealist cinema influenced filmmakers around the world, and helped inspire other film movements, such as the French New Wave and the Polish Film School. The Neorealist period is often simply referred to as "The Golden Age" of Italian Cinema by critics, filmmakers, and scholars.

Ossessione (1943), by Luchino Visconti.

Ossessione (1943), by Luchino Visconti.- A still shot from Rome, Open City (1945), by Roberto Rossellini.

Bicycle Thieves (1948), by Vittorio De Sica, ranked among the best movies ever made and part of the canon of classic cinema.[14]

Bicycle Thieves (1948), by Vittorio De Sica, ranked among the best movies ever made and part of the canon of classic cinema.[14]

Pink neorealism and comedy

It has been said that after Umberto D. nothing more could be added to neorealism. Possibly because of this, neorealism effectively ended with that film; subsequent works turned toward lighter atmospheres, perhaps more coherent with the improving conditions of the country, and this genre has been called pink neorealism. This trend allowed better-"equipped" actresses to become real celebrities, such as Sophia Loren, Gina Lollobrigida, Silvana Pampanini, Lucia Bosé, Barbara Bouchet, Eleonora Rossi Drago, Silvana Mangano, Virna Lisi, Claudia Cardinale and Stefania Sandrelli. Soon pink neorealism, such as Pane, amore e fantasia (1953) with Vittorio De Sica and Gina Lollobrigida, was replaced by the Commedia all'italiana, a unique genre that, born on an ideally humouristic line, talked instead very seriously about important social themes.

At this time, on the more commercial side of production, the phenomenon of Totò, a Neapolitan actor who is acclaimed as the major Italian comic, exploded. His films (often with Peppino De Filippo and almost always with Mario Castellani) expressed a sort of neorealistic satire, in the means of a guitto (a "hammy" actor) as well as with the art of the great dramatic actor he also was. A "film-machine" who produced dozens of titles per year, his repertoire was frequently repeated. His personal story (a prince born in the poorest rione (section of the city) of Naples), his unique twisted face, his special mimic expressions and his gestures created an inimitable personage and made him one of the most beloved Italians of the 1960s.

Italian Comedy is generally considered to have started with Mario Monicelli's I soliti Ignoti (Big Deal on Madonna Street, 1958) and derives its name from the title of Pietro Germi's Divorzio all'Italiana (Divorce Italian Style, 1961). For a long time this definition was used with a derogatory intention.

Vittorio Gassman, Marcello Mastroianni, Ugo Tognazzi, Alberto Sordi, Claudia Cardinale, Monica Vitti and Nino Manfredi were among the stars of these movies, that described the years of the economical reprise and investigated Italian customs, a sort of self-ethnological research.

In 1961 Dino Risi directed Una vita difficile (A Difficult Life), then Il sorpasso (The Easy Life), now a cult-movie, followed by: I Mostri (The Monsters, also known as 15 From Rome), In nome del Popolo Italiano (In the Name of the Italian People) and Profumo di donna (Scent of a Woman).

Monicelli's works include La grande guerra (The Great War), I compagni (Comrades, also known as The Organizer), L'Armata Brancaleone, Vogliamo i colonnelli (We Want the Colonels), Romanzo popolare (Popular Novel) and the Amici miei series.

A series of black-and-white films based on Don Camillo character created by the Italian writer and journalist Giovannino Guareschi were made between 1952 and 1965. These were French-Italian coproductions, and starred Fernandel as Don Camillo and Gino Cervi as Peppone. The titles are: The Little World of Don Camillo, The Return of Don Camillo, Don Camillo's Last Round, Don Camillo: Monsignor, and Don Camillo in Moscow. Mario Camerini began filming the film Don Camillo e i giovani d'oggi but had to stop filming due to Fernandel's falling ill, which resulted in his untimely death. The film was then completed in 1972 with Gastone Moschin playing the role of Don Camillo and Lionel Stander as Peppone. A Don Camillo (The World of Don Camillo) film was remade in 1983, an Italian production with Terence Hill directing and also starring as Don Camillo. Colin Blakely performed Peppone in one of his last film roles.

Hollywood on the Tiber

.jpg)

In the late 1940s, Hollywood studios began to shift production abroad to Europe. Italy was, along with Britain, one of the major destinations for American film companies. Shooting at Cinecittà, large-budget films such as Quo Vadis (1951), Roman Holiday (1953), Ben-Hur (1959), and Cleopatra (1963) were made in English with international casts and sometimes, but not always, Italian settings or themes. The heyday of what was dubbed '"Hollywood on the Tiber" was between 1950 and 1970, during which time many of the most famous names in world cinema made films in Italy.

Peplum (a.k.a. Sword and Sandal)

With the release of 1958's Hercules, starring American bodybuilder Steve Reeves, the Italian film industry gained entree to the American film market. These films, many with mythological or Bible themes, were low-budget costume/adventure dramas, and had immediate appeal with both European and American audiences. Besides the many films starring a variety of muscle men as Hercules, heroes such as Samson and Italian fictional hero Maciste were common. Sometimes dismissed as low-quality escapist fare, the Peplums allowed newer directors such as Sergio Leone and Mario Bava a means of breaking into the film industry. Some, such as Mario Bava's Hercules in the Haunted World (Italian: Ercole Al Centro Della Terra) are considered seminal works in their own right. As the genre matured, budgets sometimes increased, as evidenced in 1962's I sette gladiatori (The Seven Gladiators in 1964 US release), a wide-screen epic with impressive sets and matte-painting work. Most Peplum films were in color, whereas previous Italian efforts had often been black and white.

Duel of the Titans (1961)

Duel of the Titans (1961)- My Son, the Hero (1962)

The Spaghetti Western

On the heels of the Peplum craze, a related genre, the Spaghetti Western arose and was popular both in Italy and elsewhere. These films differed from traditional westerns by being filmed in Europe on limited budgets, but featured vivid cinematography.

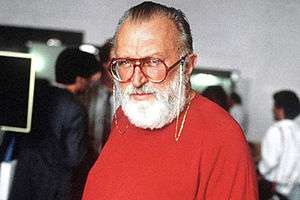

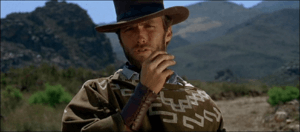

The most popular Spaghetti Westerns were those of Sergio Leone, whose Dollars Trilogy (A Fistful of Dollars, an unauthorized remake of the Japanese film Yojimbo by Akira Kurosawa; For a Few Dollars More, an original sequel; and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, a World-famous prequel), featuring Clint Eastwood as a character marketed as "the Man with No Name" and notorious scores by Ennio Morricone, came to define the genre along with Once Upon a Time in the West.

Another popular Spaghetti Western film is Django, starring Franco Nero as the titular character, another Yojimbo plagiarism, which was followed by both an authorized sequel (Django Strikes Again) and an overwhelming number of unauthorized uses of the same character in other films.

Also considered Spaghetti Westerns is a film genre which combined traditional western ambiance with a Commedia all'italiana-type comedy; films including They Call Me Trinity and Trinity Is STILL My Name!, which featured Bud Spencer and Terence Hill, the stage names of Carlo Pedersoli and Mario Girotti.

Clint Eastwood as the Man with No Name in For a Few Dollars More, part of Sergio Leone's Dollars Trilogy.

Clint Eastwood as the Man with No Name in For a Few Dollars More, part of Sergio Leone's Dollars Trilogy..jpg)

Giallo (Thriller/Horror)

During the 1960s and 70s, Italian filmmakers Mario Bava, Riccardo Freda, Antonio Margheriti and Dario Argento developed giallo horror films that become classics and influenced the genre in other countries. Representative films include: Black Sunday, Castle of Blood, Twitch of the Death Nerve, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, Deep Red and Suspiria.

Due to the success of the James Bond film series the Italian film industry made large amounts of imitations and spoofs in the Eurospy genre from 1964-1967.

Following the 1960s boom of shockumentary "Mondo films" such as Gualtiero Jacopetti's Mondo Cane, during the late 1970s and early 1980s, Italian cinema became internationally synonymous with violent horror films. These films were primarily produced for the video market and were credited with fueling the "video nasty" era in the United Kingdom.

Directors in this genre included Lucio Fulci, Joe D'Amato, Umberto Lenzi and Ruggero Deodato. Some of their films faced legal challenges in the United Kingdom; after the Video Recordings Act of 1984, it became a legal offense to sell a copy of such films as Cannibal Holocaust and SS Experiment Camp. Italian films of this period are usually grouped together as exploitation films.

Several countries charged Italian studios with exceeding the boundaries of acceptability with their late-1970s Nazi exploitation films, inspired by American movies such as Ilsa, She Wolf of the SS. The Italian works included the notorious but comparatively tame SS Experiment Camp and the far more graphic Last Orgy of the Third Reich (Italian: L'ultima orgia del III Reich). These films showed, in great detail, sexual crimes against prisoners at concentration camps. These films may still be banned in the United Kingdom and other countries.

Barbara Steele in Black Sunday (1960)

Barbara Steele in Black Sunday (1960) A scene from Blood and Black Lace (1964)

A scene from Blood and Black Lace (1964) Giuliana Calandra in a famous scene from Deep Red (1975)

Giuliana Calandra in a famous scene from Deep Red (1975) Suzy (Jessica Harper) and Sara (Stefania Casini) in Suspiria, the first film in Dario Argento's "The Three Mothers" trilogy

Suzy (Jessica Harper) and Sara (Stefania Casini) in Suspiria, the first film in Dario Argento's "The Three Mothers" trilogy

Poliziotteschi

Poliziotteschi (Italian pronunciation: [polittsjotˈteski]; plural of poliziottesco) films constitute a subgenre of crime and action film that emerged in Italy in the late 1960s and reached the height of their popularity in the 1970s. They are also known as polizieschi all'italiana, Euro-crime, Italo-crime, spaghetti crime films or simply Italian crime films. Most notable international actors acted in this genre of films such Alain Delon, Henry Silva, Fred Williamson, Charles Bronson, Tomas Milian and others international stars.

The 1980s crisis

Between the late 1970s and mid 1980s, Italian cinema was in crisis; "art films" became increasingly isolated, separating from the mainstream Italian cinema.

Among the major artistic films of this era were La città delle donne, E la nave va, Ginger and Fred by Fellini, L'albero degli zoccoli by Ermanno Olmi (winner of the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival), La notte di San Lorenzo by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani, Antonioni's Identificazione di una donna, and Bianca and La messa è finita by Nanni Moretti. Although not entirely Italian, Bertolucci's The Last Emperor, winner of 9 Oscars, and Once Upon a Time in America of Sergio Leone came out of this period also.

During this time, commedia sexy all'italiana films, described as "trash films", were popular in Italy. These comedy films were of little artistic value and reached their popularity by confronting Italian social taboos, most notably in the sexual sphere. Actors such as Lino Banfi, Diego Abatantuono, Alvaro Vitali, Gloria Guida, Barbara Bouchet and Edwige Fenech owe much of their popularity to these films.

Also considered part of the trash genre are films which feature Ugo Fantozzi, a character invented by Paolo Villaggio for his TV sketches and newspaper short stories. Although Villaggio's movies tend to bridge trash comedy with a more elevated social satire; this character had a great impact on Italian society, to such a degree that the adjective fantozziano entered the lexicon. Of the many films telling of Fantozzi's misadventures, the most notable and famous were Fantozzi and Il secondo tragico Fantozzi, but many other were produced.

1990 to present

A new generation of directors has helped return Italian cinema to a healthy level since the end of the 1980s. Probably the most noted film of the period is Nuovo Cinema Paradiso, for which Giuseppe Tornatore won a 1989 Oscar (awarded in 1990) for Best Foreign Language Film. This award was followed when Gabriele Salvatores's Mediterraneo won the same prize for 1991. Il Postino: The Postman (1994), directed by and starring Massimo Troisi, received five nominations at the Academy Awards, and won for Best Original Score. Another exploit was in 1998 when Roberto Benigni won three oscars for his movie Life Is Beautiful (La vita è bella) (Best Actor, Best Foreign Film, Best Music). In 2001 Nanni Moretti's film The Son's Room (La stanza del figlio) received the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival.

Other noteworthy recent Italian films include: Jona che visse nella balena directed by Roberto Faenza, Il grande cocomero by Francesca Archibugi, The Profession of Arms (Il mestiere delle armi) by Olmi, L'ora di religione by Marco Bellocchio, Il ladro di bambini, Lamerica, The Keys to the House (Le chiavi di casa) by Gianni Amelio, I'm Not Scared (Io non ho paura) by Gabriele Salvatores, Le fate ignoranti, Facing Windows (La finestra di fronte) by Ferzan Özpetek, Good Morning, Night (Buongiorno, notte) by Marco Bellocchio, The Best of Youth (La meglio gioventù) by Marco Tullio Giordana, The Beast in the Heart (La bestia nel cuore) by Cristina Comencini.

In 2008 Paolo Sorrentino's Il Divo, a biographical film based on the life of Giulio Andreotti, won the Jury prize and Gomorra, a crime drama film, directed by Matteo Garrone won the Gran Prix at the Cannes Film Festival.

Paolo Sorrentino's The Great Beauty (La Grande Bellezza) won the 2014 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

The two highest-grossing Italian films in Italy have both been directed by Gennaro Nunziante and starred Checco Zalone: Sole a catinelle (2013) with €51.8 million, and Quo Vado? (2016) with €65.3 million.[16][17]

They Call Me Jeeg, a 2016 critically acclaimed superhero film directed by Gabriele Mainetti and starring Claudio Santamaria, won many awards, such as eight David di Donatello, two Nastro d'Argento, and a Globo d'oro.

Gianfranco Rosi's documentary film Fire at Sea (2016) won the Golden Bear at the 66th Berlin International Film Festival. They Call Me Jeeg and Fire at Sea were also selected as the Italian entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 89th Academy Awards, but they were not nominated.[18]

Other successful 2010s Italian films include: Vincere by Marco Bellocchio, The First Beautiful Thing (La prima cosa bella), Human Capital (Il capitale umano) and Like Crazy (La pazza gioia) by Paolo Virzì, We Have a Pope (Habemus Papam) and Mia Madre by Nanni Moretti, Caesar Must Die (Cesare deve morire) by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani, Don't Be Bad (Non essere cattivo) by Claudio Caligari, Romanzo Criminale by Michele Placido (that spawned a TV series, Romanzo criminale - La serie), Youth (La giovinezza) by Paolo Sorrentino, Suburra by Stefano Sollima, Perfect Strangers (Perfetti sconosciuti) by Paolo Genovese, Mediterranea and A Ciambra by Jonas Carpignano, Tale of Tales (Il racconto dei racconti) and Dogman by Matteo Garrone, and Italian Race (Veloce come il vento) and The First King: Birth of an Empire (Il primo re) by Matteo Rovere.

Call Me by Your Name (2017), the final installment in Luca Guadagnino's thematic Desire trilogy, following I Am Love (2009) and A Bigger Splash (2015), received widespread acclaim and numerous accolades, including the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay in 2018.

Italian Academy Award winners

After the United States and the United Kingdom, Italy has the most Academy Awards wins.

Italy is the most awarded country at the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, with 14 awards won, 3 Special Awards and 31 nominations. Winners with the year of the ceremony:

- Shoeshine (1947), by Vittorio De Sica (Honorary Award)

- Bicycle Thieves (1949), by Vittorio De Sica (Honorary Award)

- The Walls of Malapaga (1950), by René Clément (Honorary Award)

- La Strada (1956), by Federico Fellini

- Nights of Cabiria (1957), by Federico Fellini

- 8½ (1963), by Federico Fellini

- Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow (1964), by Vittorio De Sica

- Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (1970), by Elio Petri

- The Garden of the Finzi-Continis (1971), by Vittorio De Sica

- Amarcord (1973), by Federico Fellini

- Cinema Paradiso (1989), by Giuseppe Tornatore

- Mediterraneo (1992), by Gabriele Salvatores

- Life Is Beautiful (1998), by Roberto Benigni

- The Great Beauty (2013), by Paolo Sorrentino

In 1961, Sophia Loren won the Academy Award for Best Actress for her role as a woman who is raped in World War II, along with her adolescent daughter, in Vittorio De Sica's Two Women. She was the first actress to win an Academy Award for a performance in any foreign language, and the second Italian leading lady Oscar-winner, after Anna Magnani for The Rose Tattoo. In 1998, Roberto Benigni was the first Italian actor to win for the Best Actor for Life Is Beautiful.

Italian-born filmmaker Frank Capra won three times at the Academy Award for Best Director, for It Happened One Night, Mr. Deeds Goes to Town and You Can't Take It with You. Bernardo Bertolucci won the award for The Last Emperor, and also Best Adapted Screenplay for the same movie.

Ennio De Concini, Alfredo Giannetti and Pietro Germi won the award for Best Original Screenplay for Divorce Italian Style. The Academy Award for Best Film Editing was won by Gabriella Cristiani for The Last Emperor and by Pietro Scalia for JFK and Black Hawk Down.

The award for Best Original Score was won by Nino Rota for The Godfather Part II; Giorgio Moroder for Midnight Express; Nicola Piovani for Life is Beautiful; Dario Marianelli for Atonement; and Ennio Morricone for The Hateful Eight. Giorgio Moroder also won the award for Best Original Song for Flashdance and Top Gun.

The Italian winners at the Academy Award for Best Production Design are Dario Simoni for Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago; Elio Altramura and Gianni Quaranta for A Room with a View; Bruno Cesari, Osvaldo Desideri and Ferdinando Scarfiotti for The Last Emperor; Luciana Arrighi for Howards End; and Dante Ferretti and Francesca Lo Schiavo for The Aviator, Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street and Hugo.

The winners at the Academy Award for Best Cinematography are: Tony Gaudio for Anthony Adverse; Pasqualino De Santis for Romeo and Juliet; Vittorio Storaro for Apocalypse Now, Reds and The Last Emperor; and Mauro Fiore for Avatar.

The winners at the Academy Award for Best Costume Design are Piero Gherardi for La dolce vita and 8½; Vittorio Nino Novarese for Cleopatra and Cromwell; Danilo Donati for The Taming of the Shrew, Romeo and Juliet, and Fellini's Casanova; Franca Squarciapino for Cyrano de Bergerac; Gabriella Pescucci for The Age of Innocence; and Milena Canonero for Barry Lyndon, Chariots of Fire, Marie Antoinette and The Grand Budapest Hotel.

Special effects artist Carlo Rambaldi won three Oscars: one Special Achievement Academy Award for Best Visual Effects for King Kong[19] and two Academy Awards for Best Visual Effects for Alien[20] (1979) and E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.[21] The Academy Award for Best Makeup and Hairstyling was won by Manlio Rocchetti for Driving Miss Daisy, and Alessandro Bertolazzi and Giorgio Gregorini for Suicide Squad.

Sophia Loren, Federico Fellini, Michelangelo Antonioni, Dino De Laurentiis, Ennio Morricone, and Piero Tosi also received the Academy Honorary Award.

Festivals

- Venice Film Festival, founded in 1932, is the world's oldest film festival, and one of the most prestigious and publicized

- Bari International Film Festival

- Beyond Media

- BigScreen Festival

- Capri Hollywood International Film Festival

- Chieti Film Festival

- Il Cinema Ritrovato

- CinemadaMare Film Festival

- Cortomobile

- Courmayeur Noir Film Festival

- Ecologico International Film Festival

- Fantafestival

- Festival del Cinema all'Aperto "Accordi @ DISACCORDI"

- First Car Film Festival

- Giffoni Film Festival

- Gran Paradiso Film Festival

- Grolla d'oro

- Io Isabella International Film Week

- Ischia Film Festival

- Italian Environmental Film Festival

- Jalari in corto

- Lucca Film Festival

- MedFilm Festival

- Milan Film Festival

- People and Religions – Terni Film Festival

- Pordenone Silent Film Festival

- River to River. Florence Indian Film Festival

- Riviera International Film Festival

- Rome Film Festival

- Salerno Film Festival

- Sardinia International Ethnographic Film Festival

- Taormina Film Fest

- Torino Film Festival

- Trieste Film Festival

- VIEW Fest

Auteurs

Italy has produced many important cinematography auteurs, including Federico Fellini, Michelangelo Antonioni, Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio De Sica, Luchino Visconti, Ettore Scola, Sergio Leone, Luigi Comencini, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Bernardo Bertolucci, Franco Zeffirelli, Ermanno Olmi, Valerio Zurlini, Florestano Vancini, Mario Monicelli, Marco Ferreri, Elio Petri, Dino Risi and Mauro Bolognini. These directors' works often span many decades and genres. Present auteurs include Giuseppe Tornatore, Marco Bellocchio, Nanni Moretti, Gabriele Salvatores, Gianni Amelio, Dario Argento and Paolo Sorrentino.

See also

- Media of Italy

- Cinema of the world

- History of cinema

- List of actors from Italy

- List of actresses from Italy

- List of film directors from Italy

- List of Italian movies

- List of highest-grossing films in Italy

Notes

- From top left to bottom right: Vittorio De Sica, Sophia Loren, Marcello Mastroianni, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Roberto Rossellini, Sergio Leone, Nino Manfredi, Luchino Visconti, Alberto Sordi, Totò, Gina Lollobrigida, Claudia Cardinale, Anna Magnani, Roberto Benigni, Michelangelo Antonioni, Giancarlo Giannini, Ugo Tognazzi, Bud Spencer, Isabella Rossellini, Federico Fellini, Mario Monicelli, Virna Lisi, Ettore Scola, Alvaro Vitali, and Monica Bellucci

References

- "Table 8: Cinema Infrastructure - Capacity". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- "Table 6: Share of Top 3 distributors (Excel)". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- "Tutti i numeri del cinema italiano 2013" (PDF). ANICA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- "Country Profiles". Europa Cinemas. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- Peter Bondanella (2009). A History of Italian Cinema. A&C Black. ISBN 9781441160690.

- Luzzi, Joseph (2016-03-30). A Cinema of Poetry: Aesthetics of the Italian Art Film. ISBN 9781421419848.

- Katz, Ephraim, "Italy," The Film Encyclopedia (New York: HarperResource, 2001), pp. 682-685.

- "La Biennale di Venezia – The origin". Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- Angelini, F. Pucci Materiali per una storia del cinema delle origini (Materials for a history of early cinema) 1981. "... allo stato attuale delle ricerche, la prima proiezione nelle Marche viene ospitata al Caffè Centrale di Ancona: ottobre 1896" ("... The present state of research, the first screening will be hosted in the Marches of Ancona at the Café Central: October 1896")

- Welle, John P. (2004). "Early Cinima, Dante's Inferno of 1911, and the Origins of Italian Film Culture". In Iannucci, Amilcare A. (ed.). Dante, Cinema, and Television. University of Toronto Press. pp. 36, 38–40. ISBN 0-8020-8827-9.

- Steve Ricci, Cinema and Fascism: Italian Film and Society, 1922-1943 (University of California Press, 2008), p. 4.

- Ronald Bergan, The Film Book (Penguin, 2011), p. 154.

- Ricci, Cinema and Fascism, p. 169.

- Ebert, Roger. "The Bicycle Thief / Bicycle Thieves (1949)". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- Shapiro, Michael J. (1 August 2008). "Slow Looking: The Ethics and Politics of Aesthetics: Jill Bennett, Empathic Vision: Affect, Trauma, and Contemporary Art (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005); Mark Reinhardt, Holly Edwards, and Erina Duganne, Beautiful Suffering: Photography and the Traffic in Pain (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2007); Gillo Pontecorvo, director, The Battle of Algiers (Criterion: Special Three-Disc Edition, 2004)". Millennium: Journal of International Studies. 37: 181–197. doi:10.1177/0305829808093770.

- Anderson, Ariston (January 4, 2016). "Italy Box Office: Local Hit 'Quo Vado?' Sets Opening Records". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved January 4, 2016.

- Lyman, Eric J. (November 4, 2013). "Italian Comedy 'Sun in Buckets' Sets New Opening Weekend Sales Record". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved January 4, 2016.

- Anderson, Ariston (26 September 2016). "Oscars: Italy Selects 'Fire at Sea' for Foreign-Language Category". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- 49th Academy Awards (Monday, March 28, 1977), official lists of winners and nominees in the Oscars.org website

- 52nd Academy Awards (Monday, April 14, 1980), official lists of winners and nominees in the Oscars.org website

- 55th Academy Awards (Monday, April 11, 1983), official lists of winners and nominees in the Oscars.org website

- Bacon, Henry. 1998. Visconti: Explorations of Beauty and Decay. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Ben-Ghiat, Ruth. “The Fascist War Trilogy”, in Roberto Rossellini: Magician of the Real. Eds. David Forgacs, Sarah Lutton, & Geoffrey Nowell-Smith. London: BFI

- Bernardi, Sandro. 2000. “Rosselini's Landscapes: Nature, Myth, History”, in Roberto Rossellini: Magician of the Real. Eds. David Forgacs, Sarah Lutton, & Geoffrey Nowell-Smith. London: BFI.

- Bondanella, Peter. 2002. The Films of Federico Fellini. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-57573-7

- Bondanella, Peter. 2002. Italian Cinema: From Neorealism to the Present, 3rd edn. New York–London: Continuum

- Brunetta, Gian Piero. 2009. The History of Italian Cinema: A Guide to Italian Film from Its Origins to the Twenty-First Century. Trans. by Jeremy Parzen. Princeton: Princeton University Press (ital. original 2003).

- Celli, Carlo & Marga Cottino-Jones. 2007. A New Guide to Italian Cinema. New York: Palgrave MacMillan

- Cherchi Usai, Paolo. 1997. Italy: Spectacle and Melodrama. Trans. by Geoffrey Nowell-Smith. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Clark, Martin. 1984. Modern Italy 1871-1982. London: Longman.

- Forgacs, David. 2000. “Introduction: Rossellini and the Critics”, in Roberto Rossellini: Magician of the Real. Eds. David Forgacs, Sarah Lutton, & Geoffrey Nowell-Smith. London: BFI

- Forgacs, David, Sarah Lutton, & Geoffrey Nowell-Smith, eds. 2000. Roberto Rossellini: Magician of the Real. London: BFI

- Genovese, Nino & Sebastiano Gesù, eds. Verga e il cinema. Con una sceneggiatura verghiana inedita di Cavalleria rusticana, testo di Gesualdo Bufalino. Catania: Giuseppe Maimone Editore, 1996.

- Gesù, Sebastiano & Laura Maccarrone, eds. Ercole Patti: Un letterato al cinema. Catania: Giuseppe Maimone Editore, 2004.

- Gesù, Sebastiano. L'Etna nel cinema: Un vulcano di celluloide. Catania: Giuseppe Maimone Editore, 2005.

- Gesù, Sebastiano, ed. Francesco Rosi. Catania: Giuseppe Maimone Editore, 1993.

- Gesù, Sebastiano & Elena Russo, Le Madonie, cinema ad alte quote. Catania: Giuseppe Maimone Editore, 1995 (Nuovo Cinema Paradiso e L'Uomo delle Stelle)

- Indiana, Gary. 2000. Salo or The 120 Days of Sodom. London, BFI

- Kemp, Philip. 2002. “The Son's Room”, Sight and Sound 12, no. 3 (March): 56.

- Kezich, Tullio & Sebastiano Gesù, eds. Salvatore Giuliano. Catania: Giuseppe Maimone Editore, 1993.

- Landy, Marcia. 2000. Italian Film. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Mancini, Elaine. 1985 Struggles of the Italian Film Industry during Fascism 1930-1935. Ann Arbor: UMI Press

- Marcus, Millicent. 1993. Filmmaking by the Book. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press

- Marcus, Millicent. 1986. Italian Film in the Light of Neorealism. Princeton: Princeton University Press

- Morandini, Morando. 1997. ' Vittorio de Sica' . Nowell-Smith Geoffrey Ed : Oxford History of World Cinema. Oxford : Oxford University Press.

- Morandini, Morando. 1997. 'Italy from Fascism to Neo-Realism'. Nowell-Smith Geoffrey Ed : Oxford History of World Cinema. Oxford : Oxford University Press.

- Nowell-Smith, Geoffrey. 2003. Luchino Visconti, 3rd edn. London: British Film Institute.

- Nowell-Smith, Geoffrey. 2000. “North and South, East and West: Rossellini and Politics”, in Roberto Rossellini: Magician of the Real. Eds. David Forgacs, Sarah Lutton, & Geoffrey Nowell-Smith. London: BFI

- Reich, Jacqueline & Piero Garofalo, eds. 2002. Re-viewing Fascism: Italian Cinema, 1922-1943. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Reichardt, Dagmar & Alberto Bianchi, eds. Letteratura e cinema. Edited and with a preface by Dagmar Reichardt and Alberto Bianchi. Florence: Franco Cesati Editore, (Civiltà italiana. Terza serie, no. 5), 2014. ISBN 978-88-7667-501-0

- Rohdie, Sam. 2002. Fellini Lexicon. London: BFI

- Rohdie, Sam. 2000. “India”, in Roberto Rossellini: Magician of the Real. Eds. David Forgacs, Sarah Lutton, & Geoffrey Nowell-Smith. London: BFI

- Rohdie, Sam. Rocco and his Brothers. London: BFI

- Sitney, P. Adams. 1995. Vital Crises in Italian Cinema. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-77688-8

- Sorlin, Pierre. 1996. Italian National Cinema. London: Routledge

- Wagstaff, Christopher. 2000. “Rossellini and Neo-Realism”, in Roberto Rossellini: Magician of the Real. Eds. David Forgacs, Sarah Lutton, & Geoffrey Nowell-Smith. London: BFI

- Wood, Mary. 2002. “Bernado Bertolucci in context”, in Fifty Contemporary Filmmakers. Ed. by Yvonne Tasker. London: Routledge.

- Wood, Michael. 2003. “Death becomes Visconti”, Sight and Sound 13, no. 5 (May 2003): 24–27.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)