Ancient Carthage

Carthage (/ˈkɑːrθədʒ/; Punic: 𐤒𐤓𐤕𐤟𐤇𐤃𐤔𐤕, romanized: Qart-ḥadašt, lit. 'New City'; Latin: Carthāgō)[3] was an ancient Phoenician city-state located in present-day Tunisia. Founded around 814 BC as a colony of Tyre, within centuries it grew to become the center of the Carthaginian Empire, a major commercial and maritime power that dominated the western Mediterranean until the mid third century BC.[4][5][6]

Carthage 𐤒𐤓𐤕𐤟𐤇𐤃𐤔𐤕 Qart-ḥadašt | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 814 BC–146 BC | |||||||||||||||

Attributed Military standard (based on R. Hook's illustrations for Wise's "Armies of the Carthaginian Wars, 265 – 146 BC")

Symbol of the goddess Tanit

(religious or supposed state insignia) | |||||||||||||||

Carthage and its dependencies in 264 BC | |||||||||||||||

| Capital | Carthage | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Punic, Phoenician, Berber (Numidian), Ancient Greek | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Punic religion | ||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Carthaginian | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy until c. 480 BC, republic led by Shophets thereafter[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Antiquity | ||||||||||||||

• Founded by Phoenician settlers | c. 814 BC | ||||||||||||||

• Independence from Tyre | c. 650 BC | ||||||||||||||

• Destroyed by Rome | 146 BC | ||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||

• 221 BC[2] | 3,700,000–4,300,000 (entire empire) | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Carthaginian shekel | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

After gaining independence in the mid seventh century BC, Carthage gradually expanded its political hegemony across northwest Africa, Iberia, and the major islands of the western Mediterranean. Its sphere of influence encompassed an informal empire of colonies, client states, and allies. Despite its cosmopolitan character, the core aspects of Carthaginian culture, language, religion, and identity remained Phoenician, also known as Punic.

At its height in the third century BC, Carthage was the dominant economic, political, and military power in the Mediterranean. It was among the largest and richest cities in the ancient world, and served as the region's leading commercial and industrial hub. Carthage's vast trade network extended from the Levant to West Africa, and from sub-Saharan Africa to northern Europe, providing an array of agricultural goods, precious metals, and manufactured products. This mercantile empire was secured by a large and powerful navy, which for centuries was unmatched in size and strength.

Carthage's rise brought it into conflict with many neighbors and rivals, from the indigenous Berbers of North Africa to the nascent Roman Republic.[7] Following a series of conflicts with the Sicilian Greeks (c. 580–265 BC), growing competition with Rome culminated in the Punic Wars (264–146 BC), which saw some of the largest and most sophisticated battles in antiquity. In 146 BC, after the third and final Punic War, the Romans destroyed Carthage and established a new city in its place.[8] All remaining Carthaginian dependencies, as well as other Phoenician city-states, came under Roman rule by the first century AD.

Carthage is mostly remembered for its long and bitter conflict with Rome, which almost threatened the rise of the Roman Republic and changed the course of Western civilization. Due to the destruction of virtually all Carthaginian texts after the Third Punic War, much of what is known about its civilization comes from Roman and Greek authors, many of whom wrote well after its destruction, and who to varying degrees were influenced by attitudes shaped by the Punic Wars.

Etymology

The name Carthage /ˈkɑːrθɪdʒ/ is the Early Modern anglicisation of Middle French Carthage /kar.taʒ/, from Latin 'Carthāgō' and 'Karthāgō' (cf. Greek Karkhēdōn (Καρχηδών) and Etruscan *Carθaza) from the Punic 'qrt-ḥdšt' (𐤒𐤓𐤕 𐤇𐤃𐤔𐤕) "new city".

Punic, which is often used synonymously with Carthaginian, derives from the Latin poenus and punicus, based on the Ancient Greek word Φοῖνιξ (Phoinix), pl. Φοίνικες (Phoinikes), an exonym used to describe the Canaanite port towns with which the Greeks traded. Latin later borrowed the Greek term a second time as phoenix, pl. phoenices.[9] Both Punic and Phoenician were used by the Romans and Greeks to refer to Phoenicians across the Mediterranean; modern scholars use the term Punic exclusively for Phoenicians in the western Mediterranean, such as the Carthaginians. Specific Punic groups are often referred to with hyphenated terms, like "Siculo-Punic" for Phoenicians in Sicily or "Sardo-Punic" for those in Sardinia. Ancient Greek authors sometimes referred to the Punic inhabitants of North Africa ('Libya') as 'Liby-Phoenicians'.

It is unclear what term, if any, the Carthaginians used to refer to themselves. The Phoenician homeland in the Levant was natively known as 𐤐𐤕 (Pūt) and its people as the 𐤐𐤍𐤉𐤌 (Pōnnim). Ancient Egyptians accounts suggest the people from the region identified as Kenaani or Kinaani, equivalent to Canaanite.[10] A passage from Augustine has often been interpreted as indicating that the Punic-speakers in North Africa called themselves Chanani (Canaanites),[11] but it has recently been argued that this is a misreading.[12] Numismatic evidence from Sicily shows that some western Phoenicians made use of the term Phoinix.[13]

Sources

Compared to contemporary civilizations such as Rome and Greece, far less is known about Carthage; most indigenous records were lost following the wholesale destruction of the city after the Third Punic War. Sources of knowledge are limited to ancient translations of Punic texts into Greek and Latin, Punic inscriptions on monuments and buildings, and archaeological findings of Carthage's material culture.[14] The majority of available primary sources about Carthage were written by Greek and Roman historians, most notably Livy, Polybius, Appian, Cornelius Nepos, Silius Italicus, Plutarch, Dio Cassius, and Herodotus. These authors came from cultures that were nearly always in competition, if not open conflict, with Carthage; the Greeks with respect to Sicily,[15] and the Romans over dominance of the western Mediterranean.[16] Inevitably, foreign accounts of Carthage usually reflect significant bias, especially those written during or after the Punic Wars, when the interpretatio Romana perpetuated a "malicious and distorted view".[17] Excavations of ancient Carthaginian sites since the late 19th century have brought to light more material evidence that either contradict or confirm aspects of the traditional picture of Carthage; however, many of these findings remain ambiguous.

History

Foundation legends

The specific date, circumstances, and motivations concerning Carthage's founding are unknown. All surviving accounts of Carthage's foundation come from Latin and Greek literature, which are generally legendary in nature but may have some basis in fact.

The standard foundation myth across all sources is that the city was founded by colonists from the ancient Phoenician city-state of Tyre, led by its exiled princess Dido (also known as Queen Elissa or Alissar).[18] Elissa's brother, Pygmalion (Phoenician: Pummayaton) had murdered her husband, the high priest of the city, and taken power as a tyrant. Elissa and her allies escape his reign and establish Carthage, which becomes a prosperous city under her rule as queen.

The Roman historian Justin, writing in the second century AD, provides an account of the city's founding based on the earlier work of Trogus. Princess Elissa is the daughter of King Belus II of Tyre, who upon his death bequeaths the throne jointly to her and her brother Pygmalion. After cheating his sister out of her share of political power, Pygmalion murders her husband Acerbas (Phoenician: Zakarbaal), also known as Sychaeus, the High Priest of Melqart, whose wealth and power he covets.[19] Before her tyrannical brother can take her late husband's wealth, Elissa immediately flees with her followers to establish a new city abroad.

Upon landing in North Africa, she is greeted by the local Berber chieftain, Iarbas (also called Hiarbas) who promises to cede as much land as could be covered by a single ox hide. With her characteristic cleverness, Dido cuts the hide into very thin strips and lays them end to end until they encircle the entire hill of Byrsa. While digging to set the foundation of their new settlement, the Tyrians discover the head of an ox, an omen that the city would be wealthy "but laborious and always enslaved". In response they move the site of the city elsewhere, where the head of a horse is found, which in Phoenician culture is a symbol of courage and conquest. The horse foretells where Dido's new city will rise, becoming the emblem of Carthage, derived from the Phoenician Qart-Hadasht, meaning "New City".

The city's wealth and prosperity attracts both Phoenicians from nearby Utica and the indigenous Libyans, whose king Iarbas now seeks Elissa's hand in marriage. Threatened with war should she refuse, and also loyal to the memory of her deceased husband, the queen orders a funeral pyre to be built, where she commits suicide by stabbing herself with a sword. She is thereafter worshiped as a goddess by the people of Carthage, who are described as brave in battle but prone to the "cruel religious ceremony" of human sacrifice, even of children, whenever they seek divine relief from troubles of any kind.

Virgil's epic poem the Aeneid—written over a century after the Third Punic War—tells the mythical story of the Trojan hero Aeneas and his journey towards founding Rome, inextricably tying together the founding myths, and ultimate fates, of both Rome and Carthage. Its introduction begins by mentioning "an ancient city" that many readers likely assumed was Rome or Troy,[20] but goes on to describe it as a place "held by colonists from Tyre, opposite Italy . .. a city of great wealth and ruthless in the pursuit of war. Its name was Carthage, and Juno is said to have loved it more than any other place ... But she had heard that there was rising from the blood of Troy a race of men who in days to come would overthrow this Tyrian citadel ... [and] sack the land of Libya."[20]

Virgil describes Queen Elissa—for whom he uses the ancient Greek name, Dido, meaning "beloved"—as an esteemed, clever, but ultimately tragic character. As in other legends, the impetus for her escape is her tyrannical brother Pygmalion, whose secret murder of her husband is revealed to her in a dream. Cleverly exploiting her brother's greed, Dido tricks Pygmalion into supporting her journey to find and bring back riches for him. Through this ruse she sets sail with gold and allies secretly in search of a new home.

As in Justin's account, upon landing in North Africa, Dido is greeted by Iarbas, and after he offers as much land as could be covered by a single ox hide, she cuts the hide into very thin strips and encircles all of Byrsa. While digging to set the foundation of their new settlement, the Tyrians discover the head of a horse, which in Phoenician culture is a symbol of courage and conquest. The horse foretells where Dido's new city will rise, becoming the emblem of the "New City" Carthage. In just seven years since their exodus from Tyre, the Carthaginians build a successful kingdom under Dido's rule. She is adored by her subjects and presented with a festival of praise. Virgil portrays her character as even more noble when she offers asylum to Aeneas and his men, who had recently escaped from Troy. The two fall in love during a hunting expedition, and Dido comes to believe they will marry. Jupiter sends a spirit in the form of the messenger god, Mercury, to remind Aeneas that his mission is not to stay in Carthage with his new-found love Dido, but to sail to Italy to found Rome. The Trojan departs, leaving Dido so heartbroken that she commits suicide by stabbing herself upon a funeral pyre with his sword. As she lies dying, she predicts eternal strife between Aeneas' people and her own, proclaiming "rise up from my bones, avenging spirit" in an invocation of Hannibal.[21] Aeneas sees the smoke from the pyre as he sails away, and though he does not know the fate of Dido, he identifies it as a bad omen. Ultimately, he goes on to found the Roman Kingdom, the predecessor of the Roman Empire.

Like Justin, Virgil's story essentially conveys Rome's attitude towards Carthage, as exemplified by Cato the Elder's famous utterance, "Carthago delenda est"—"Carthage must be destroyed".[22] In essence, Rome and Carthage were fated for conflict: Aeneas chose Rome over Dido, eliciting her dying curse upon his Roman descendants, and thus providing a mythical, fatalistic backdrop for a century of bitter conflict between Rome and Carthage.

These stories typify the Roman attitude towards Carthage: a level of grudging respect and acknowledgement of their bravery, prosperity, and even their city's seniority to Rome, along with derision of their cruelty, deviousness, and decadence, as exemplified by their practice of human sacrifice.

Settlement as Tyrian colony (c. 814 BC)

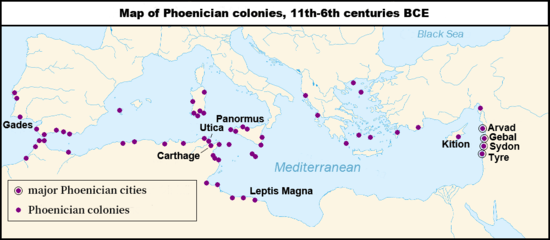

To facilitate their commercial ventures, the Phoenicians established numerous colonies and trading posts along the coasts of the Mediterranean. Organized in fiercely independent city-states, the Phoenicians lacked the numbers or even the desire to expand overseas; most colonies had fewer than 1,000 inhabitants, and only a few, including Carthage, would grow larger.[23] Motives for colonization were usually practical, such as seeking safe harbors for their merchant fleets, maintaining a monopoly on an area's natural resources, satisfying the demand for trade goods, and finding areas where they could trade freely without outside interference.[24][25][26] Over time many Phoenicians also sought to escape their tributary obligations to foreign powers that had subjugated the Phoenician homeland. Another motivating factor was competition with the Greeks, who became a nascent maritime power and began establishing colonies across the Mediterranean and the Black Sea.[27]

The first Phoenician colonies in the western Mediterranean grew up on the two paths to Iberia's mineral wealth: along the northwest African coast and on Sicily, Sardinia, and the Balearic Islands.[28] As the largest and wealthiest city-state among the Phoenicians, Tyre led the way in settling or controlling coastal areas. Strabo claims that the Tyrians alone founded three hundred colonies on the west African coast; though clearly an exaggeration, many colonies did arise in Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria, Iberia, and to a much lesser extent, on the arid coast of Libya.[29] They were usually established as trading stations at intervals of about 30 to 50 kilometres along the African coast.[30]

By the time they gained a foothold in Africa, the Phoenicians were already present in Cyprus, Crete, Corsica, the Balearic Islands, Sardinia, and Sicily, as well as on the European mainland, in what are today Genoa and Marseilles.[31] Foreshadowing the later Sicilian Wars, settlements in Crete and Sicily continually clashed with the Greeks, and Phoenician control over all of Sicily was brief.[32] Nearly all these areas would come under the leadership and protection of Carthage,[33] which eventually founded cities of its own, especially after the decline of Tyre and Sidon.[34]

The site of Carthage was likely chosen by the Tyrians for several reasons. It was located in the central shore of the Gulf of Tunis, which gave it access to the Mediterranean sea while shielding it from the region's infamously violent storms. It was also close to the strategically vital Strait of Sicily, a key bottleneck for maritime trade between the eat and west. The terrain proved as invaluable as the geography. The city was built on a hilly, triangular peninsula backed by the Lake of Tunis, which provided abundant supplies of fish and a place for safe harbor. The peninsula was connected to the mainland by a narrow strip of land, which combined with the rough surrounding terrain, made the city easily defensible; a citadel was built on Byrsa, a low hill overlooking the sea. Finally, Carthage would be conduit of two major trade routes: one between the Tyrian colony of Cadiz in southern Spain, which supplied raw materials for manufacturing in Tyre, and the other between North Africa and the northern Mediterranean, namely Sicily, Italy, and Greece.[35]

Independence, expansion and hegemony (c. 650–264 BC)

In contrast to most Phoenician colonies, Carthage grew larger and more quickly thanks to its combination of favorable climate, arable land, and lucrative trade routes. Within just one century of its founding, its population rose to 30,000. Meanwhile, its mother city, which for centuries was the preeminent economic and political center of Phoenician,[36] saw its status begin to wane in the seventh century BC, following a succession of sieges by the Babylonians.[37][38] By this time, its Carthaginian colony had become immensely wealthy from its strategic location and extensive trade network. Unlike many other Phoenician city-states and dependencies, Carthage grew prosperous not only from maritime commerce but from its proximity to fertile agricultural land and rich mineral deposits. As the main hub for trade between Africa and the rest of the ancient world, it also provided a myriad of rare and luxurious goods, including terracotta figurines and masks, jewelry, delicately carved ivories, ostrich eggs, and a variety of foods and wine.

Carthage's growing economic prominence coincided with a nascent national identity. Although Carthaginians remained staunchly Phoenician in their customs and faith, by at least the seventh century BC, they had developed a distinct Punic culture infused with local influences.[39] Certain deities became more prominent in the Carthaginian pantheon than in Phoenicia; into the fifth century BC, the Carthaginians were worshiping Greek deities such as Demeter.[40] Carthage may have also retained religious practices that had long fallen out of favor in Tyre, such as child sacrifice. Similarly, it spoke its own Punic dialect of Phoenician, which also reflected contributions by neighboring peoples.

These trends most likely precipitated the colony's emergence as an independent polity. Though the specific date and circumstances are unknown, Carthage most likely became independent around 650 BC, when it embarked on its own colonization efforts across the western Mediterranean. It nonetheless maintained amicable cultural, political, and commercial ties with its founding city and the Phoenician homeland; it continued to receive migrants from Tyre, and for a time continued the practice of sending annual tribute to Tyre's temple of Melqart, albeit at irregular intervals.

By the sixth century BC, Tyre's power declined further still after its voluntary submission to the Persian king Cambyses (r. 530–522 BC), which resulted in the incorporation of the Phoenician homeland into the Persian empire.[41] Lacking sufficient naval strength, Cambyses sought Tyrian assistance for his planned conquest of Carthage, which may indicate that the former Tyrian colony had become wealthy enough to warrant a long and difficult expedition. Herodotus claims that the Tyrians refused to cooperate due to their affinity for Carthage, causing the Persian king to abort his campaign. Though it escaped reprisal, Tyre's status as Phoenicia's leading city was significantly circumscribed; its rival, Sidon, subsequently garnered more support from the Persians. However, it too remained subjugated, leading the way for Carthage to fill the vacuum as the leading Phoenician political power.

Formation and characteristic of the empire

It is unknown what factors influenced the citizens of Carthage, unlike those of other Mediterranean Phoenician colonies, to create an economic and political hegemony; the nearby city of Utica was far older and enjoyed the same geographical and political advantages, but ultimately came under the latter's influence. One theory is that Babylonian and Persian domination of the Phoenician homeland produced refugees that swelled Carthage's population and transferred the culture, wealth, and traditions of Tyre to Carthage.[42] The threat to the Phoenician trade monopoly—by Etruscan and Greek competition in the west, and through foreign subjugation of its homeland in the east—also created both the conditions and the motive for Carthage to solidify its dominance of the region in order to preserve and further its commercial interests.

Another contributing factor may have been domestic politics: while little is known of Carthage's government and leadership prior to the third century BCE, the reign of Mago (c. 550–530), whose Magonid family dominated Carthaginian politics in subsequent decades, precipitated Carthage's rise. Mago, who was general of the army, is credited with initiating the practice of recruiting subject peoples and mercenaries, because "the population of Carthage was too small to provide defence for so widely scattered an empire." Libyans, Iberians, Sardinians, and Corsicans were soon enlisted for Magonid's expansionist campaigns across the region.[43]

By the beginning of the fifth century BC, Carthage had become the commercial center of the western Mediterranean, and would remain so for roughly the next three centuries.[44] Although they retained the traditional Phoenician affinity for maritime trade and commerce, the Carthaginians departed significantly in their imperial and military ambitions: whereas the Phoenician city states rarely engaged in territorial conquest, Carthage became an expansionist power in an effort to access new sources of wealth and trade. It took control of all nearby Phoenician colonies (including Hadrumetum, Utica, Hippo Diarrhytus and Kerkouane), subjugated many neighboring Libyan tribes, and occupied coastal North Africa from Morocco to western Libya.[45] Carthage expanded its influence into the Mediterranean, controlling Sardinia, Malta, the Balearic Islands, and the western half of Sicily,[46] where coastal fortresses such as Motya and Lilybaeum secured their possessions. The Iberian Peninsula, which was rich in precious metals, saw some of the largest and most important Carthaginian settlements outside North Africa,[47] though the degree of political influence before the conquest by Hamilcar Barca (237–228 BC) is disputed.[48][49] Its growing wealth and power, commensurate with the continued foreign subjugation of the Phoenician homeland, led to Carthage soon supplanting Sidon as the supreme Phoenician city-state.[50]

Carthage's empire was largely informal and multifaceted, consisting of varying levels of control exercised in equally variable ways. It established new colonies, repopulated and reinforced older ones, created defensive arrangements with other Phoenician city states, and acquired territories directly by conquest. While some Phoenician colonies willingly submitted to Carthage, paying tribute and giving up their foreign policy, others in Iberia and Sardinia resisted Carthaginian efforts. Whereas other Phoenician cities never exercised actual control of the colonies, the Carthaginians appointed magistrates to directly control their own (a policy that would lead to a number of Iberian towns siding with the Romans during the Punic Wars).[51] However, in many other instances, Carthage's hegemony was established through treaties, alliances, tributary obligations, and other such arrangements. It had elements of the Delian League led by Athens (allies shared funding and manpower for defense), the Spartan Kingdom (subject peoples serving as serfs for the Punic elite and state) and, to a lesser extent, the Roman Republic (allies contributing manpower and tribute for Rome's war machine).

In 509 BC, Carthage and Rome signed the first of several treaties demarcating their respective influence and commercial activities.[52][53] This is the first known source demonstrating that Carthage had gained control over Sicily and Sardinia. The treaty also conveys the extent to which Carthage was, at the very least, on equal terms with Rome, whose influence was limited to parts of central and southern Italy. Carthaginian dominance of the sea reflected not only its Phoenician heritage, but an approach empire-building that differed greatly from Rome. Carthage emphasized maritime trade over territorial expansion, and accordingly focused its settlements and influence on coastal areas, while investing more on its navy. For similar reasons, ambitions were more commercial than imperial, which is why its empire took the form of treaties and political arrangements more so than conquest. By contrast, the Romans focused on expanding and consolidating their control over the rest of mainland Italy, and would so aim to extend its control well beyond its homeland. These differences would prove key in the conduct and trajectory of the later Punic Wars.

By the third century BC, Carthage was the center of a sprawling network of colonies and client states. It controlled more territory than the Roman Republic, and became one of the largest and most prosperous cities in the Mediterranean, numbering a quarter of a million inhabitants. Only the rising Roman Republic could rival its supremacy over the region, which inevitably led to competition and open conflict.

Conflict with the Greeks (580–265 BC)

Unlike the existential conflict that drove the later Punic Wars with Rome, the conflict between Carthage and the Greeks was due more to economic factors rather than ideological and cultural differences; each sought to advance their own commercial interests and influence by controlling key trade routes. The Phoenician and Greek city-states each embarked on maritime trade and colonization across the Mediterranean, and although the Phoenicians were initially the dominant traders, Greek competition increasingly undermined their monopoly. Both sides had begun establishing colonies, trading posts, and commercial relations in the western Mediterranean roughly contemporaneously, between the ninth to eighth century. Notwithstanding occasional skirmishes between Punic and Phoenician settlements, the increased presence of both peoples led to growing competition and ultimately open conflict, especially in Sicily.

First Sicilian War

Carthage's economic successes, buoyed by its vast maritime trade network, led to the development of a powerful Carthaginian navy to protect and secure vital control of shipping lanes.[54] Its increased hegemony brought it into increasing conflict with the Greeks of Syracuse, who also sought control of central Mediterranean.[55] Founded in the mid seventh century BC, Syracuse had risen to become one of the wealthiest and most powerful Greek city states, and the preeminent Greek in the region.

The island of Sicily, lying at Carthage's doorstep, became the main arena on which this conflict played out. From their earliest days, both the Greeks and Phoenicians had been attracted to the large, centrally-located island, each establishing a large number of colonies and trading posts along its coasts; battles raged between these settlements for centuries, with neither side ever having total, long-term control over the island.[56]

In 480 BC, Gelo, the tyrant of Syracuse, attempted to unite the island under his rule with the backing of other Greek city-states.[57] Threatened by the potential power of a united Sicily, Carthage intervened militarily, led by King Hamilcar of the Magonid dynasty. Traditional accounts, including by Herodotus and Diodorus, number Hamilcar's army at around 3,000; though likely exaggerated, it was likely of formidable strength.

While sailing to Sicily, Hamilcar suffered losses due to poor weather. Landing at Panormus (modern-day Palermo),[58] he spent three days reorganizing his forces and repairing his battered fleet. The Carthaginians marched along the coast to Himera, making camp before engaging in battle against the forces of Syracuse and its ally Agrigentum.[59] The Greeks won a decisive victory, inflicting heavy losses on the Carthaginians, including their leader Hamilcar, who was either killed during the battle or committed suicide in shame.[60] As a result, the Carthaginian nobility sued for peace.

The conflict proved to be a major turning point for Carthage. Though it would retain some presence in Sicily, most of the island would remain in Greek (and later Roman) hands. The Carthaginians would never again expand their territory or sphere of influence on the island to any meaningful degree, instead turning their attention to securing or increasing their hold in North Africa and Iberia.[61][62] The death of King Hamilcar and the disastrous conduct of the war also prompted political reforms that established an oligarchic republic.[63] Carthage would henceforth constrain its rulers through assemblies of both nobles and the common people.

Second Sicilian War

By 410 BC, Carthage had recovered from its serious defeats in Sicily. It had conquered much of modern-day Tunisia and founded new colonies across northern Africa. It also extended its reach well beyond the Mediterranean; Hanno the Navigator journeyed down the West African coast,[64][65] and Himilco the Navigator had explored the European Atlantic coast.[66] Expeditions were also led into Morocco and Senegal, as well as the Atlantic.[67] The same year, the Iberian colonies seceded, cutting off Carthage from a major source of silver and copper. The loss of such strategically important mineral wealth, combined with the desire to exercise firmer control over shipping routes, led Hannibal Mago, grandson of Hamilcar, to make preparations to reclaim Sicily.

In 409 BC, Hannibal Mago set out for Sicily with his force. He captured the smaller cities of Selinus (modern Selinunte) and Himera—where the Carthaginians had been dealt a humiliating defeat seventy year prior—before returning triumphantly to Carthage with the spoils of war.[68] But the primary enemy, Syracuse, remained untouched and in 405 BC, Hannibal Mago led a second Carthaginian expedition to claim the rest of the island.

This time, however, he met with fiercer resistance as well as misfortune. During the siege of Agrigentum, Carthaginian forces were ravaged by plague, which claimed Hannibal Mago himself.[69] His successor, Himilco, managed to extend the campaign, capturing the city of Gela and repeatedly defeating the army of Dionysius of Syracuse. But he, too, was struck with plague and forced to sue for peace before returning to Carthage.

By 398 BC, Dionysius had regained his strength and broke the peace treaty, striking at the Carthaginian stronghold of Motya in western Sicily. Himilco responded decisively, leading an expedition that not only reclaimed Motya, but also captured Messene (present-day Messina).[70] Within a year, the Carthaginians were besieging Syracuse itself, and came close to victory until the plague once again ravaged and reduced their forces.[71]

The fighting in Sicily swung in favor of Carthage less than a decade later in 387 BC. After winning a naval battle off the coast of Catania, Himilco laid siege to Syracuse with 50,000 Carthaginians, but yet another epidemic struck down thousands of them. With the enemy assault stalled and weakened, Dionysius then launched a surprise counterattack by land and sea, destroying all the Carthaginian ships while its crews were ashore. At the same time, his ground forces stormed the besiegers' lines and routed them. Himilco and his chief officers abandoned their army and fled Sicily.[72] Once again, the Carthaginians were forced to press for peace. Returning to Carthage in disgrace, Himilco was met with contempt and committed suicide by starving himself.[73]

Notwithstanding consistently poor luck and costly reversals, Sicily remained an obsession for Carthage. Over the next fifty years, an uneasy peace reigned, as Carthaginian and Greek forces engaged in constant skirmishes. By 340 BC, Carthage had been pushed entirely into the southwest corner of the island.

Third Sicilian War

In 315 BC, Carthage now found itself on the defensive in Sicily, as Agathocles of Syracuse broke the terms of the peace treaty and sought to dominate the entire island. Within four years, he seized Messene, laid siege to Akragas, and invaded the last Carthaginian holdings on the island.

Hamilcar, grandson of Hanno the Great, led the Carthaginian response with great success. Within a year of their arrival, the Carthaginians controlled almost all of Sicily and were besieging Syracuse. In desperation, Agathocles secretly led an expedition of 14,000 men to attack Carthage.[74] The Carthaginians were forced to recall Hamilcar and most of his army from Sicily to face the new and unexpected threat. Although Agathocles' forces were eventually defeated in 307 BC, he managed to escape back to Sicily and negotiate peace, thus maintaining the status quo and Syracuse as a stronghold of Greek power in Sicily.

Pyrrhic War (280–275 BC)

Carthage once again found itself drawn into a war in Sicily, this time by Pyrrhus of Epirus, who challenged both Roman and Carthaginian supremacy over the Mediterranean.[75] Pyrrhus sent an advance guard of 3,000 infantry, under the command of his adviser Cineaus, to the Roman city of Tarentum in southern Italy. Meanwhile, he marched the main army across the Greek peninsula and won several victories over the Thessalians and Athenians. After securing the Greek mainland, Pyrrhus rejoined his advance guard in Tarentum to conquer southern Italy.

During the Italian campaign, Pyrrhus received envoys from the Sicilian cities of Agrigentum, Syracuse, and Leontini seeking military aid to end Carthaginian dominance over the island.[76][77] He responded with reinforcements consisting of 20,000 infantry, 3,000 cavalry, and 20 war elephants supported by some 200 ships.[78][79] The campaign against Carthage was largely a success, pushing the Carthaginians back to western Siciliy, and capturing the city-fortress of Eryx, though it failed to take Lilybaeum.[80]

Following these losses, Carthage sued for peace, but Pyrrhus refused unless Carthage renounced its claims to Sicily entirely. Plutarch claims Pyrrhus aimed to conquer Carthage itself, and to this end began outfitting an expedition. However, his ruthless treatment of the Sicilian Greeks, including his execution of two Sicilian rulers, elicited such animosity that he was forced to withdraw from Sicily and focus his attention on southern Italy.[81][82]

Pyrrhus' campaigns in Italy proved inconclusive, and he eventually withdrew to Epirus. For the Carthaginians, this meant a return to the status quo, but for the Romans, this allowed Magna Graecia to absorbed into their sphere of influence, bringing Rome closer to complete domination of the Italian peninsula. Rome's control over Italy, and its success in holding firm against Pyrrhus' campaign, paved the way to future Rome-Carthage conflicts known as the Punic Wars.

Punic Wars (264–146 BC)

When Agathocles of Syracuse died in 288 BC, a large company of Italian mercenaries previously in his service found themselves suddenly unemployed. Naming themselves Mamertines ("Sons of Mars"), they seized the city of Messana and became a law unto themselves, terrorizing the surrounding countryside.[83]

The Mamertines became a growing threat to Carthage and Syracuse alike. In 265 BC, Hiero II of Syracuse, former general of Pyrrhus, took action against them.[84] Faced with a vastly superior force, the Mamertines divided into two factions, one advocating surrender to Carthage, the other preferring to seek aid from Rome. While the Roman Senate debated the best course of action, the Carthaginians eagerly agreed to send a garrison to Messana. Carthaginian forces were admitted to the city, and a Carthaginian fleet sailed into the Messanan harbor. However, soon afterwards they began negotiating with Hiero. Alarmed, the Mamertines sent another embassy to Rome asking them to expel the Carthaginians.

Hiero's intervention placed Carthage's military forces directly across the Strait of Messina, the narrow channel of water that separated Sicily from Italy. Moreover, the presence of the Carthaginian fleet gave them effective control over this strategically important bottleneck and demonstrated a clear and present danger to nearby Rome and her interests. As a result, the Roman Assembly, although reluctant to ally with a band of mercenaries, sent an expeditionary force to return control of Messana to the Mamertines.

The subsequent Roman attack on Carthaginian forces at Messana triggered the first of the Punic Wars.[85] Over the course of the next century, these three major conflicts between Rome and Carthage would determine the course of Western civilization. The wars included a dramatic Carthaginian invasion led by Hannibal, which nearly brought an end to Rome.

During the First Punic Wars the Romans under the command of Marcus Atilius Regulus managed to land in Africa, though were ultimately repelled by the Carthaginians.[84] Notwithstanding its decisive defense of its homeland, as well as some initial naval victories, Carthage suffered a succession of losses that forced it to sue for peace. Shortly after the First Punic War, Carthage also faced a major mercenary revolt that dramatically changed its internal political landscape, bringing the influential Barcid family to prominence.[86] The war also impacted Carthage's international standing, as Rome used the events of the war to back its claim over Sardinia and Corsica, which it promptly seized.

Lingering mutual animosity and renewed tensions along their borderlands led to the Second Punic War (218 to 202 BC), which involved factions from across the western and eastern Mediterranean.[87] The war is marked by Hannibal's surprising overland journey to Rome, particularly his costly and strategically bold crossing of the Alps. His entrance into northern Italy was followed by his reinforcement by Gaulish allies and crushing victories over Roman armies in the battle of the Trebia and the giant ambush at Trasimene.[88] Against his skill on the battlefield the Romans employed the Fabian strategy, which resorted to skirmishes in lieu of direct engagement, with the aim delaying and gradually weakening his forces. While effective, this approach was politically unpopular, as it ran contrary to traditional military strategy. The Romans thus resorted to another major field battle at Cannae, but despite their superior numbers, they suffered a crushing defeat.[89][90]

Consequently, many Roman allies went over to Carthage, prolonging the war in Italy for over a decade, during which more Roman armies were nearly consistently destroyed on the battlefield. Despite these setbacks, the Romans had the manpower to absorb such losses and replenish their ranks. Along with their superior capability in siegecraft, they were able to recapture all the major cities that had joined the enemy, as well as defeat a Carthaginian attempt to reinforce Hannibal at the Battle of the Metaurus.[91] Meanwhile, in Iberia, which served as the main source of manpower for the Carthaginian army, a second Roman expedition under Scipio Africanus took New Carthage and ended Carthaginian rule over the peninsula in the Battle of Ilipa.[92][93]

The final showdown was the Battle of Zama, which took place in the Carthaginian heartland of Tunisia. After trouncing Carthaginian forces at the battles of Utica and the Great Plains, Scipio Africanus forced Hannibal to abandon his increasingly stalled campaign in Italy. Despite the latter's superior numbers and innovative tactics, the Carthaginians suffered a crushing and decisive defeat. After years of costly fighting that brought them to the verge of destruction, the Romans imposed harsh and retributive peace conditions on Carthage. In addition to a large financial indemnity, the Carthaginians were stripped of their once-proud navy and reduced only to their North African territory. In effect, Carthage became a Roman client state.[94]

The third and final Punic War began in 149 BC, largely due to the efforts of hawkish Roman senators, led by Cato the Elder, to finish Carthage off once and for all.[95] Cato was known for finishing nearly every speech in the Senate, regardless of the subject, with the phrase ceterum censeo Carthaginem esse delendam—"Moreover, I am of the opinion that Carthage ought to be destroyed". In particular, the growing Roman Republic sought the famously rich agricultural lands of Carthage and its African territories, which had been known to the Romans following their invasion in the previous Punic War.[96][97][98] Carthage's border war with Rome's ally Numidia, though initiated by the latter, nonetheless provided the pretext for Rome to declare war.

The Third Punic War was a much smaller and shorter engagement than its predecessors, primarily consisting of a single main action, the Battle of Carthage. However, given their significantly reduced size, military, and wealth, the Carthaginians managed to mount a surprisingly strong initial defense. The Roman invasion was soon stalled by defeats at Lake Tunis, Nepheris, and Hippagreta; even the truncated Carthaginian navy managed to inflict severe losses on a Roman fleet through the use of fire ships.[99] Carthage itself managed to resist the Roman siege for three years, until Scipio Aemilianus—the adopted grandson of Scipio Africanus—was appointed consul and took command of the assault.

Notwithstanding its impressive resistance, Carthage's defeat was ultimately a foregone conclusion, given the far larger size and strength of the Roman Republic. Though it was the smallest of the Punic Wars, the third war was to be the most decisive: The complete destruction of the city of Carthage,[100] the annexation of all remaining Carthaginian territory by Rome,[101] and the death or enslavement of tens of thousands of Carthaginians.[102][103] The war ended Carthage's independent existence, and consequently eliminated the last Phoenician political power.[104]

Aftermath

Following Carthage's destruction, Rome established Africa Proconsularis, its first province in Africa, which roughly corresponded to Carthage's northwest African territory. Utica, which had allied itself with Rome during the final war, was granted tax privileges and made the regional capital, subsequently becoming the leading center of Punic trade and culture.

In 122 BC, Gaius Gracchus, a populist Roman senator, founded the short-lived colony of Colonia Iunonia, after the Latin name for the Punic goddess Tanit, Iuno Caelestis. Located near the site of Carthage, its purpose was to provide arable lands for impoverished farmers, but it was soon abolished by the Roman Senate to undermine Gracchus' power.

Nearly a century after the fall of the Punic Carthage, a new "Roman Carthage" was built on the same site by Julius Caesar between 49 and 44 BC. It soon became the center of the province of Africa, which was a major breadbasket of the Roman Empire and one of its wealthiest provinces. By the first century, it had grown to be the second-largest city in the western half of the Roman Empire, with a peak population of 500,000.

Punic language, identity, and culture persisted several centuries into Roman rule. In the early third century, at least two Roman emperors—Septimius Severus and his son and successor Caracalla—were of Punic descent. In the fourth century, Augustine of Hippo, himself of Berber heritage, noted that Punic was still spoken in the region by people who identified as Kn'nm, or "Chanani", as the Carthaginians had designated themselves. Settlements across North Africa, Sardinia, and Sicily continued to speak and write Punic, as evidenced by inscriptions on temples, tombs, public monuments, and artwork. Punic names were still used until at least the fourth century, even by prominent denizens of Roman Africa.

Aside from Mago's agricultural treatise, some Punic ideas and innovations remained mainstream in Roman culture. Pomegranates, a popular Carthaginian commodity, were known as mala Punica ("Punic Apples"). A mosaic technique of patterned terracotta pieces was called pavimentum Punicum. The threshing board, which had been introduced to the Romans by Carthage, was thus known as the plostellum Punicum.[105]

Government and politics

As was common in antiquity, including among the Phoenician city-states, Carthage may initially have been a monarchy, although modern scholars debate whether this stemmed from a misunderstanding by Greek writers.[106] Phoenician kings did not usually exercise absolute power, but consulted with a body of advisors called the adirim ("mighty ones"), which most likely was composed of the wealthiest members of society, namely merchants.[107] Carthage seems to have been ruled by the blm, a group of nobles who exercised all important matters of state, including religion, administration, and the military.[106] Within this cabal was a hierarchy topped by the dominant family, usually the wealthiest members of the merchant class, which had some sort of executive power. Although described as kings by the Greeks, records indicate that different families held power at different times, which strongly implied a nonhereditary system of government dependent on the support or appointment of the consultative body.[106]

Carthage's political system changed dramatically after 483 BC, following the total rout of its forces at the battle of Himera during the First Sicilian War.[108] The ruling Magonid clan—of which the defeated King Hamilcar was a member—was compelled to allow representative institutions. Carthage became an oligarchic republic with a system of checks and balances and a fairly high degree of public accountability and participation. Its government now consisted of several different institutions and offices, principally the sufetes, the Adirim (or supreme council), the Hundred and Four, and the Popular Assembly, all of which shared or divided power in intricate ways.

At the head of the Carthaginian state were two sufetes (Punic: 𐤔𐤐𐤈, šūfeṭ) or "judges", who had judicial and executive powers.[Note 1] Though both Greek and Roman authors commonly referred to them as "kings", after at least by the late fifth century BC the sufetes were nonhereditary offices elected annually from among the wealthiest and most influential families. Livy likens them to Roman consuls, ruling mostly through collegiality and handling matters of state such as the convocation and presidency of the Adirim, the submission of business to the People's Assembly, and service as trial judges.[109] This practice may have descended from the plutocratic oligarchies that limited the sufetes' power in the first Phoenician cities.[110] In the sixth century BC, Tyre adopted a similar system, with two sufetes chosen from the most powerful noble families for short terms.[111] Tyre has been described during this period as a "republic headed by elective magistrates".[112] Some modern historians compare Carthage's sufetes to executive presidents.[113][114][Note 2] It is unknown how sufetes were elected or who was eligible to serve. Uniquely among executive offices in antiquity, they had had no power over the military, as generals were chosen by the administration.

Aristocratic families were represented in a supreme council called the Adirim, which the Romans refer to as a "senate" and the Greeks liken to Sparta's Gerousia, or council of elders. The Adirim had a broad range of powers, including supervising the treasury and conducting foreign affairs.[113] During the Second Punic War it reportedly exercised some military power.[113]

According to Aristotle, a special judicial tribunal known as the One Hundred and Four (Phoenician: 𐤌𐤀𐤕 or miat)[115] served as Carthage's "highest constitutional authority". Although he compares it to the Spartan ephors, unlike its Spartan counterpart, which had a wide range of political powers, the tribunal's main function was to oversee the actions of generals and other officials to ensure they were serving the best interests of the republic.[110] The One Hundred and Four had the power to impose fines and even crucifixion as punishment. Panels of special commissioners, called pentarchies, were appointed from the tribunal to deal with various state affairs.[113] Numerous junior officials and special commissioners were responsible for different aspects of government, such as public works, tax-collecting, and the administration of the state treasury.[113][116]

Although Carthage was firmly controlled by oligarchs, its government included some democratic elements, including elected legislators, trade unions, town meetings, and a popular assembly.[117] In his Politics, written in the mid fourth century BC, Aristotle claims that unless the sufetes and the supreme council reached a unanimous decision on a matter, an assembly of the people had the decisive vote—unlike in the Greek republics of Sparta and Crete. It is unclear whether this assembly was ad hoc or a formal institution. In any event, Aristotle claims that "the voice of the people was predominant in the deliberations" and "the people themselves solved problems".[40] He also praises Carthage's political system for its "balanced" elements of monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy, believing that each element was kept in check by the other two. Aristotle's Athenian contemporary, Isocrates, elevates Carthage's political system as the best in antiquity, equaled only by Sparta's.[118]

It is noteworthy that Aristotle ascribes to Carthage a position among the Greek states, because the Greeks firmly believed that they alone had the ability to found 'poleis', whereas the barbarians used to live in tribal societies ('ethne'). It is therefore remarkable that Aristotle maintained that the Carthaginians were the only non-Greek people who had created a 'polis'.[119]

Confirming Aristotle's claims, Polybius, in book 6 of his Histories, states that during the Punic Wars, the Carthaginian public held more sway over the government than the Romans did over theirs. However, he regards this development as a fatal flaw, since it led the Carthaginians to bicker and debate while the Romans, through the more oligarchic Senate, acted more quickly and decisively.[120] This may have been due to the influence and populism of the Barcid faction, which between the end of the First Punic War and the end of the Second Punic War dominated Carthage's government, military, and overseas territories.[121][122]

Carthage reportedly had a constitution of some kind. Aristotle makes mention of a Carthaginian constitution, which he compares favorably to its well regarded Spartan counterpart, describing it as sophisticated, functional, and fulfilling "all needs of moderation and justice".[123][124] Eratosthenes, head of the Library of Alexandria, confirms the constitutional nature of Carthage's government, as he states that the Greeks were wrong to regard all non-Greeks as barbarians, since the Carthaginians, as well as the Romans, had constitutions.

Carthage's republican system appears to have extended to the rest of its empire, though to what extent and in what form is unknown. The term sufet was used for officials throughout its colonies and territories; inscriptions from Punic-era Sardinia are dated with four names: the sufetes of the island as well as of Carthage.[125] This suggests some degree of political coordination between local and colonial Carthaginians, perhaps through a regional hierarchy of sufetes.

Citizenship

Like the republics of the Latin and Hellenistic worlds, Carthage likely had some notion of citizenship, distinguishing those who could participate in the political process and who had certain rights, privileges, and duties. However, it is uncertain whether such a distinction existed, much less the specific criteria.[107] For example, while the Popular Assembly is described as giving a political voice to the common people, there is no mention of any restrictions based on citizenship. Carthaginian society was complex and divided into many different classes, including slaves, peasants, aristocrats, merchants, and various professionals. Moreover, Carthage's empire consisted of an often nebulous network of Punic colonies, subject peoples, client states, and allied tribes and kingdoms; it is unknown whether individuals from these different realms and nationalities formed any particular social or political class in relation to the Carthaginian government.[107]

Roman accounts suggest that Carthaginian citizens, especially those allowed to run for high office, had to prove their descent from the city's founders. This would indicate that Phoenicians were privileged over other ethnic groups, and even to fellow Phoenicians descended from later waves of settlers. However, it would also mean that someone of partial "foreign" ancestry could still be a citizen; Hamilcar, who served as a sufete in 480 BC, was half Greek.[107] Greek writers claimed that ancestry, as well as wealth and merit, were avenues to citizenship and political power. As Carthage was a mercantile society, this would imply that both citizenship and membership in the aristocracy were relatively accessible by ancient standards.

Aristotle mentions Carthaginian "associations" similar to the Hellenistic hetairiai, organizations roughly analogous to political parties or interest groups.[107] These were most likely the mizrehim referenced in Carthaginian inscriptions, of which little is known or attested, but which appeared to have been numerous in number and subject, from devotional cults to professional guilds. It is unknown whether such an association was required of citizens, as in some Greek republics like Sparta. Aristotle also describes a Carthaginian equivalent to the syssitia, communal meals that were the mark of citizenship and social class in Greek societies.[126] Once again, however, it is unclear whether Carthaginians attributed any political significance to their equivalent practice.[107]

Carthage's military provides a possible glimpse into the criteria of citizenship. Greek accounts describe a "Sacred Band of Carthage" that fought in Sicily in the mid fourth century BC, using the Hellenistic term for professional citizen soldiers selected on the basis of merit and ability.[127] Roman writings about the Punic Wars describe the core of the military, including its commanders and officers, as being made up of "Liby-Phoenicians", a broad label that included ethnic Phoenicians, those of mixed Punic-North African descent, and Libyans who had integrated into Phoenician culture.[128]

Continuance after Roman conquest

Aspects of Carthage's political system persisted well into the Roman period, albeit to varying degrees and often in Romanized form. Sufetes are mentioned in inscriptions throughout the major settlements of Roman Sardinia, indicating the office was perhaps used by Punic descendants to resist both cultural and political assimilation with their Latin conquerors. As late as the mid second century AD, two sufetes wielded power in Bithia, a city in the Roman province of Sardinia and Corsica.[129]

The Romans seemed to have actively tolerated, if not adopted, Carthaginian offices and institutions. Official state terminology of the late Roman Republic and subsequent Empire repurposed the word sufet to refer to Roman-style local magistrates serving in Africa Proconsularis, which included Carthage and its core territories.[109] Sufetes are attested to have governed over forty post-Carthaginian towns and cities, including Althiburos, Calama, Capsa, Cirta, Gadiaufala, Gales, Limisa, Mactar, and Thugga.[130] Though many were former Carthaginian settlements, some had little to no Carthaginian influence; Volubilis, in modern-day Morocco, had been part of the Kingdom of Mauretania, which became a Roman client state after the fall of Carthage.[131] The use of sufetes persisted well into the late second century AD.[132]

Sufetes were prevalent even in interior regions of Roman Africa that had never been settled by Carthage. This suggests that, unlike the Punic community of Roman Sardinia, Punic settlers and refugees endeared themselves to Roman authorities by adopting a readily intelligible government.[132] Three sufetes serving simultaneously appear in first century AD records at Althiburos, Mactar, and Thugga, reflecting a choice to adopt Punic nomenclature for Romanized institutions without the actual, traditionally balanced magistracy.[132] In those cases, a third, non-annual position of tribal or communal chieftain marked an inflection point in the assimilation of external African groups into the Roman political fold.[130]

Sufes, the Roman approximation of the term sufet, appears in at least six works of Latin literature. Erroneous references to Carthaginian "kings" with the Latin term rex betray the translations of Roman authors from Greek sources, who equated the sufet with the more monarchical basileus (Greek: βασιλεύς).[109]

Military

Army

_counting_the_rings_of_the_Roman_knights_killed_at_the_Battle_of_Cannae_(216_BC)%2C_Marble%2C_1704%2C_from_the_Gardens_of_the_Tuileries%2C_Louvre_Museum_(8270402664).jpg)

Though primarily a maritime power, since at least the reign of Mago in the early sixth century BC, Carthage's navy usually operated in support of its land campaigns, which were key to its expansion and defense.[133] As a mainly commercial empire with a relatively small native population, Carthage generally did not maintain a large, permanent, standing army.[134] According to Polybius, it relied heavily, though not exclusively, on foreign mercenaries, especially in overseas warfare.[135] Modern historians regard this as an oversimplification, as many alleged mercenaries were likely auxiliaries from allied or client states, provided through formal agreements, tributary obligations, or military pacts.[40] The Carthaginians maintained close relations, sometimes through political marriages, with the rulers of various tribes and kingdoms, most notably the Numidians (based in modern northern Algeria). These leaders would in turn provide their respective contingent of forces, sometimes even leading them in Carthaginian campaigns.[40] In any event, Carthage leveraged its vast wealth and hegemony to help fill the ranks of its military.

Contrary to popular belief, especially among the more martial Greeks and Romans, Carthage did utilize citizen soldiers—i.e., ethnic Punics/Phoenicians—particularly during the Sicilian Wars. Moreover, like their Greco-Roman contemporaries, the Carthaginians respected "military valour", with Aristotle reporting the practice of citizens wearing armbands to signify their combat experience.[133] Greek observers also described the "Sacred Band of Carthage", applying the Hellenistic term for professional citizen soldiers, who fought in Sicily in the mid fourth century BC.[127] However, after this force was destroyed by Agathocles in 310 BC, foreign mercenaries and subject peoples formed a more significant part of the army. This indicates that the Carthaginians had a capacity to adapt their military as circumstances required; when larger or more specialized forces were needed, such as during the Punic Wars, they would employ mercenaries or auxiliaries accordingly. Carthaginian citizens would be enlisted in large numbers only by necessity, such as for the pivotal Battle of Zama in the Second Punic War, or in the final siege of the city in the Third Punic War.[118]

The core of the Carthaginian army was always from its own territory in Northwest Africa, namely ethnic Libyans, Numidians, and "Liby-Phoenicians", a broad label that included ethnic Phoenicians, those of mixed Punic-North African descent, and Libyans who had integrated into Phoenician culture.[128] These troops were supported by mercenaries from different ethnic groups and geographic locations across the Mediterranean, who fought in their own national units. For instance, Celts, Balearics, and Iberians were recruited in significant numbers to fight in Sicily.[136] Greek mercenaries, who were highly valued for their skill, were hired for the Sicilian campaigns.[40] Carthage employed Iberian troops long before the Punic Wars; Herodotus and Alcibiades both describe the fighting capabilities of the Iberians among the western Mediterranean mercenaries.[137] Later, after the Barcids conquered large portions of Iberia (modern Spain and Portugal), Iberians came to form an even greater part of the Carthaginian forces, albeit based more on their loyalty to the Barcid faction than to Carthage itself. The Carthaginians also fielded slingers, soldiers armed with straps of cloth used to toss small stones at high speeds; for this they often recruited Balearic Islanders, who were reputed for their accuracy.[40]

The uniquely diverse makeup of Carthage's army, particularly during the Second Punic War, was noteworthy to the Romans; Livy characterized Hannibal's army as a "hotch-potch of the riff-raff of all nationalities." He also observed that the Carthaginians, at least under Hannibal, never forced any uniformity upon their disparate forces, which nonetheless had such a high degree of unity that they "never quarreled amongst themselves nor mutinied", even during difficult circumstances.[138] Punic officers at all levels maintained some degree of unity and coordination among these otherwise disparate forces. They also dealt with the challenge of ensuring military commands were properly communicated and translated to their respective foreign troops.[40][118]

Carthage used the diversity of its forces to its own advantage, capitalizing on the particular strengths or capabilities of each nationality. Celts and Iberians were often utilized as shock troops, North Africans as cavalry, and Campanians from southern Italy as heavy infantry. Moreover, these units would typically be deployed to nonnative lands, which ensured they had no affinity for their opponents and could surprise them with unfamiliar tactics. For example, Hannibal used Iberians and Gauls (from what is today France) for campaigns in Italy and Africa.[40]

Carthage seems to have fielded a formidable cavalry force, especially in its Northwest African homeland; a significant part of it was composed of light Numidian cavalry, who were considered "by far the best horsemen in Africa."[139] Their speed and agility proved pivotal to several Carthaginian victories, most notably the Battle of Trebia, the first major action in the Second Punic War.[140] The reputation and effectiveness of Numidian cavalry was such that the Romans utilized a contingent of their own in the decisive Battle of Zama, where they reportedly "turned the scales" in Rome's favor.[141][142] Polybius suggests that cavalry remained the force in which Carthaginian citizens were most represented following the shift to mostly foreign troops after the third century BC.[135]

Owing to Hannibal's campaigns in the Second Punic War, Carthage is perhaps best remembered for its use of the now-extinct North African elephant, which was specially trained for warfare and, among other uses, was commonly utilized for frontal assaults or as anticavalry protection. An army could field up to several hundred of these animals, but on most reported occasions fewer than a hundred were deployed. The riders of these elephants were armed with a spike and hammer to kill the elephants, in case they charged toward their own army.

Navy

The Carthaginians maintained the ancient Phoenician's reputation as skilled mariners, navigators, and shipbuilders. Polybius wrote that the Carthaginians were "more exercised in maritime affairs than any other people."[143] Its navy was one of the largest and most powerful in the Mediterranean, using serial production to maintain high numbers at moderate cost.[134] During the Second Punic War, by which time Carthage had lost most of its Mediterranean islands, it still managed to field some 300 to 350 warships. The sailors and marines of the Carthaginian navy were predominantly recruited from the Phoenician citizenry, unlike the multiethnic allied and mercenary troops of the Carthaginian army. The navy offered a stable profession and financial security for its sailors, which helped contribute to the city's political stability, since the unemployed, debt-ridden poor in other cities were frequently inclined to support revolutionary leaders in the hope of improving their own lot.[144] The reputation of her skilled sailors implies that training of oarsmen and coxswains occurred in peacetime, giving their navy a cutting edge.

In addition to its military functions, the Carthaginian navy was key to the empire's commercial dominance, helping secure trade routes, protect harbors, and even enforce trade monopolies against competitors.[118] Carthaginian fleets also served an exploratory function, most likely for the purpose of finding new trade routes or markets. Evidence exists of at least one expedition, that of Hann the Navigator, possibly sailing along the West African coast to regions south of the Tropic of Cancer.[145]

The Romans, who had little experience in naval warfare prior to the First Punic War, managed to finally defeat Carthage with a combination of reverse-engineered, captured Carthaginian ships, the recruitment of experienced Greek sailors from the ranks of its conquered cities, the unorthodox corvus device, and their superior numbers in marines and rowers. Polybius describes a tactical innovation of the Carthaginians during the Third Punic War, consisting of augmenting their few triremes with small vessels that carried hooks (to attack the oars) and fire (to attack the hulls). With this new combination, they were able to stand their ground against the numerically superior Romans for a whole day.

In addition to the use of serial production, Carthage developed complex infrastructure to support and maintain its sizable fleet. Cicero described the city as succincta portibus—"surrounded by harbours"—and accounts from Appian and Strabo describe a large and sophisticated harbor known as the Cothon (Greek: κώθων, lit. "drinking vessel").[146][147] Based on similar structures used for centuries across the Phoenician world, the Cothon was a key factor in Carthaginian naval supremacy; it is unknown how prevalent it was throughout the empire, but both Utica in northwest Africa and Motya in Sicily had comparable harbors.[148][149] Modern reconstructions that draw from both ancient descriptions and modern archaeological findings show the Cothon was divided into a rectangular merchant harbor followed by an inner protected harbor reserved for military vessels.[150] The inner harbor was circular and surrounded by an outer ring of structures partitioned into docking bays, along with an island structure at its centre that also housed naval ships. Each individual docking bay featured a raised slipway, allowing ships to be dry-docked for maintenance and repair. Above the raised docking bays was a second level consisting of warehouses where oars and rigging were kept along with supplies such as wood and canvas. The island structure had a raised "cabin" where the admiral in command could observe the whole harbor along with the surrounding sea. Altogether the inner docking complex could house up to 220 ships. The entire harbor was protected by an outer wall, while the main entrance could be closed off with iron chains.[151]

Similar to their adoption of Carthaginian naval innovations during the Punic Wars, the Romans also utilized the Cothon in their rebuilding of the city, where it helped support the region's commercial and strategic development.[152]

Language

Carthaginians spoke a variety of Phoenician called Punic, a Semitic language originating in the Carthaginians' original homeland of Phoenicia (present-day Lebanon).[153][154]

Like its parent language, Punic was written from right to left, consisted of 22 consonants without vowels, and is known mostly through inscriptions. During classical antiquity, Punic was spoken throughout Carthage's territories and spheres of influence in the western Mediterranean, namely northwest Africa and several Mediterranean islands. Although the Carthaginians maintained ties and cultural affinity with their Phoenician homeland, their Punic dialect gradually became influenced by various Berber languages spoken in and around Carthage by the ancient Libyans. Following the fall of Carthage, a "Neo-Punic" dialect emerged that diverged from Punic in terms of spelling conventions and the use of non-Semitic names, mostly of Libyco-Berber origin.

Notwithstanding the destruction of Carthage and assimilation of its people into the Roman Republic, Punic appeared to have persisted for centuries in the former Carthaginian homeland. This is best attested by Augustine of Hippo, himself of Berber descent, who spoke and understood Punic and served as the "primary source on the survival of [late] Punic". He claims the language was still spoken in his region of North Africa in the fifth century, and that there were still people who self identified as chanani (Canaanite: Carthaginian). Contemporaneous funerary texts found in Christian catacombs in Sirte, Libya bear inscriptions in Ancient Greek, Latin, and Punic, suggesting a fusion of the cultures under Roman rule.

There is evidence that Punic was still spoken and written by commoners in Sardinia at least 400 years after the Roman conquest. Aside from Augustine of Hippo, Punic was known by some literate North Africans until the second or third centuries (albeit written in Roman and Greek script) and remained spoken among peasants at least until the end of the fourth century.

Economy

Carthage's commerce extended by sea throughout the Mediterranean and perhaps as far as the Canary Islands, and by land across the Sahara desert. According to Aristotle, the Carthaginians had commercial treaties with various trading partners to regulate their exports and imports.[155][156][157] Their merchant ships, which surpassed in number even those of the original Phoenician city-states, visited every major port of the Mediterranean, as well as Britain and the Atlantic coast of Africa.[158] These ships were able to carry over 100 tons of goods.[159] Archaeological discoveries show evidence of all kinds of exchanges, from the vast quantities of tin needed for bronze-based civilizations, to all manner of textiles, ceramics, and fine metalwork. Even between the punishing Punic wars, Carthaginian merchants remained at every port in the Mediterranean, trading in harbours with warehouses or from ships beached on the coast.[160]

The empire of Carthage depended heavily on its trade with Tartessos and other cities of the Iberian peninsula,[161][162] from which it obtained vast quantities of silver, lead, copper and – most importantly – tin ore,[163] which was essential to manufacture the bronze objects that were highly prized in antiquity. Carthaginian trade relations with the Iberians, and the naval might that enforced Carthage's monopoly on this trade and the Atlantic tin trade,[164] made it the sole significant broker of tin and maker of bronze in its day. Maintaining this monopoly was one of the major sources of power and prosperity for Carthage; Carthaginian merchants strove to keep the location of the tin mines secret.[165] In addition to its exclusive role as the main distributor of tin, Carthage's central location in the Mediterranean and control of the waters between Sicily and Tunisia allowed it to control the eastern peoples' supply of tin. Carthage was also the Mediterranean's largest producer of silver, mined in Iberia and on the Northwest African coast;[166] after the tin monopoly, this was one of its most profitable trades. One mine in Iberia provided Hannibal with 300 Roman pounds (3.75 talents) of silver a day.[167][168]

Carthage's economy began as an extension of that of its parent city, Tyre.[169] Its massive merchant fleet traversed the trade routes mapped out by Tyre, and Carthage inherited from Tyre the trade in the extremely valuable dye Tyrian purple.[170] No evidence of purple dye manufacture has been found at Carthage, but mounds of shells of the murex marine snails, from which it derived, have been found in excavations of the Punic town of Kerkouane, at Dar Essafi on Cap Bon.[171] Similar mounds of murex have also been found at Djerba[172] on the Gulf of Gabes[173] in Tunisia. Strabo mentions the purple dye-works of Djerba[174] as well as those of the ancient city of Zouchis.[175][176][177] The purple dye became one of the most highly valued commodities in the ancient Mediterranean,[178] being worth fifteen to twenty times its weight in gold. In Roman society, where adult males wore the toga as a national garment, the use of the toga praetexta, decorated with a stripe of Tyrian purple about two to three inches in width along its border, was reserved for magistrates and high priests. Broad purple stripes (latus clavus) were reserved for the togas of the senatorial class, while the equestrian class had the right to wear narrow stripes (angustus clavus).[179][180]

In addition to its extensive trade network, Carthage had a diversified and advanced manufacturing sector. It produced finely embroidered silks,[181] dyed textiles of cotton, linen,[182] and wool, artistic and functional pottery, faience, incense, and perfumes.[183] Its artisans worked expertly with ivory,[184] glassware, and wood,[185] as well as with alabaster, bronze, brass, lead, gold, silver, and precious stones to create a wide array of goods, including mirrors, furniture[186] and cabinetry, beds, bedding, and pillows,[187] jewelry, arms, implements, and household items.[188] It traded in salted Atlantic fish and fish sauce (garum),[189] and brokered the manufactured, agricultural, and natural products[190] of almost every Mediterranean people.[191] Bronze engraving and stone-carving are described as having reached their zenith in the fourth and third centuries.[192]

While primarily a maritime power, Carthage also sent caravans into the interior of Africa and Persia. It traded its manufactured and agricultural goods to the coastal and interior peoples of Africa for salt, gold, timber, ivory, ebony, apes, peacocks, skins, and hides.[193] Its merchants invented the practice of sale by auction and used it to trade with the African tribes. In other ports, they tried to establish permanent warehouses or sell their goods in open-air markets. They obtained amber from Scandinavia, and from the Iberians, Gauls, and Celts received amber, tin, silver, and furs. Sardinia and Corsica produced gold and silver for Carthage, and Phoenician settlements on Malta and the Balearic Islands produced commodities that would be sent back to Carthage for large-scale distribution. The city supplied poorer civilizations with simple products such as pottery, metallic objects, and ornamentations, often displacing local manufacturing, but brought its best works to wealthier ones such as the Greeks and Etruscans. Carthage traded in almost every commodity wanted by the ancient world, including spices from Arabia, Africa and India, as well as slaves (the empire of Carthage temporarily held a portion of Europe and sent conquered barbarian warriors into North African slavery).[194]

Herodotus wrote an account around 430 BC of Carthaginian trade on the Atlantic coast of Morocco.[195] The Punic explorer and sufete of Carthage, Hanno the Navigator, led an expedition to recolonise the Atlantic coast of Morocco that may have ventured as far down the coast of Africa as Senegal and perhaps even beyond.[196] The Greek version of the Periplus of Hanno describes his voyage. Although it is not known just how far his fleet sailed on the African coastline, this short report, dating probably from the fifth or sixth century BC, identifies distinguishing geographic features such as a coastal volcano and an encounter with hairy hominids.

The Etruscan language is imperfectly deciphered, but bilingual inscriptions found in archaeological excavations at the sites of Etruscan cities indicate the Phoenicians had trading relations with the Etruscans for centuries.[197] In 1964, a shrine to Astarte, a popular Phoenician deity, was discovered in Italy containing three gold tablets with inscriptions in Etruscan and Phoenician, giving tangible proof of the Phoenician presence in the Italian peninsula at the end of the sixth century BC, long before the rise of Rome.[198] These inscriptions imply a political and commercial alliance between Carthage and the Etruscan city of Caere, which would corroborate Aristotle's statement that the Etruscans and Carthaginians were so close as to form almost one people.[199][200] The Etruscan city-states were, at times, both commercial partners of Carthage and military allies.[201]

Agriculture

Carthage's North African hinterland was famed in antiquity for its fertile soil and ability to support abundant livestock and crops. Diodorus shares an eyewitness account from the fourth century BC describing lush gardens, verdant plantations, large and luxurious estates, and a complex network of canals and irrigation channels. Roman envoys visiting in the mid-second century BC, including Cato the Censor—known for his fondness for agriculture as much as for his low regard of foreign cultures—described the Carthaginian countryside as thriving with both human and animal life. Polybius, writing of his visit during the same period, claims that a greater number and variety of livestock were raised in Carthage than anywhere else in the known world.[202]

Initially, the Carthaginians, like their Phoenician founders, did not engage much in agriculture: Like nearly all Phoenician cities and colonies, Carthage was primarily settled along the coast; evidence of settlement of the hinterland dates only to the late fourth century BC, several centuries after its founding. As they settled further inland, the Carthaginians eventually made the most of the region's rich soil, developing what may have been one of the most prosperous and diversified agricultural sectors of its time. They practised highly advanced and productive agriculture,[203] using iron ploughs, irrigation,[204] crop rotation, threshing machines, hand-driven rotary mills, and horse mills, the latter two being invented by the Carthaginians in the late sixth century BC and mid to late fourth century BC, respectively.[205][206]