Italian Wars

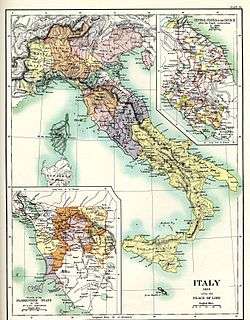

The Italian Wars, often referred to as the Great Wars of Italy and sometimes as the Habsburg–Valois Wars, were a long series of wars fought between 1494 and 1559 in Italy during the Renaissance. The Italian peninsula, economically advanced but politically divided among several states, became the main battleground for European supremacy. The conflicts involved the major powers of Italy and Europe, in a series of events that followed the end of the 40-year long Peace of Lodi agreed in 1454 with the formation of the Italic League.

| Italian Wars | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French–Habsburg rivalry | |||||||

The Peace of Nice signed in 1538 between Francis I of France and Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor with the mediation of Pope Paul III. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| |||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Italy | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

|

Early

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

Post-Roman Kingdoms

|

||||||||||

|

Medieval

|

||||||||||

|

Early modern

|

||||||||||

|

Modern

|

||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

The collapse of the alliance in the 1490s left Italy open to the ambitions of Charles VIII of France, who invaded the Kingdom of Naples in 1494 on the ground of a dynastic claim. The French were however forced to leave Naples after the Republic of Venice formed an alliance with Maximilian I of Austria and Ferdinand V of Spain. In 1499, Louis XII of France initiated a second campaign against Naples by first taking control of the Duchy of Milan thanks to Cesare Borgia, son of Pope Alexander VI and condottiero for Louis XII, marking an open alliance between the Papacy and France. The second war ended in 1503, when Ferdinand of Spain (already ruler of Sicily and Sardinia) captured the Kingdom of Naples from Louis XII.

The new Pope, Julius II (1503-1513), reversed the policies of the Borgias and exiled Cesare. With France taking over almost all of Northern Italy after defeating Venice at the Battle of Agnadello, and Ferdinand of Aragon emerging as ruler of the whole south, Julius II planned to “free Italy from the barbarians” and orchestrated the recapture of the peninsula. After Spain recognized the Two Sicilies as a papal fief, Julius II personally led his armed forces at the Siege of Mirandola, and subsequently forced the French of Louis XII out of Italy in alliance with Switzerland and the Holy Roman Empire. The sudden death of Julius II and the Battle of Marignano led to the restoration of the status quo ante bellum in 1516: the treaties of Brussels and Noyon, mediated by Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor and Pope Leo X, recognized French control in the north (excluding the Venetian republic) and Spanish control in the south.

War resumed in 1521 as Pope Leo X and Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (simultaneously ruler of Austria, the Spanish kingdoms, and the Low Countries) expelled French forces from Milan. Francis I of France reacted by descending in Italy and fighting Imperial forces at the Battle of Pavia (1525), where he was captured and forced to give French territory to the Habsburg Netherlands of Charles V. Following his liberation, Francis I initiated a new war in Italy during which mutinous Germanic troops of Lutheran faith sacked Rome (1527) and expelled the Medici from Florence. After ordering the retreat of Imperial troops from the Papal States, Charles V restored the occupied French territory to Francis I on the condition that France abandoned northern Italy ("Peace of the Ladies"). At the Congress of Bologna in 1530, Charles V received the Imperial title of King of Italy by Pope Clement VII. In exchange, the Pope obtained the restoration of the Medici family as the ruling dynasty of Florence.

Following Catholic victories in Vienna and Tunis against the Ottomans, a new congress (1536) was held in Rome between Charles V and Pope Paul III to discuss the hypothesis of an ecumenical council to deal with Protestantism. Despite fears of conciliarism within the curia, Pope Paul III ultimately saw a council as an opportunity to end the Catholic Imperial-French wars in Italy by uniting the anti-Calvinist French royalty with the Habsburgs against a common enemy. Indeed, the conflict had resumed at the Lombard-Piedmontese border with the French occupation of the Savoyard state soon after Charles V took the vacant Duchy of Milan. Therefore, Pope Paul III favored the "Peace of Nice" between Francis I and the Emperor (1538) as well as the subsequent "Peace of Crespy" (1544). The Council of Trent began in 1545, but Lutheran princes refused to recognize it with the result of entering a war with the Emperor (quickly lost) and allowing the Pope to dominate the council and initiate the counter-reformation. Around 1547, papal and imperial factions clashed for political supremacy and a series of conspiracies took place in several courts of Italy. The assassination of Pier Luigi Farnese, Duke of Parma and son of the Pope, led to the suspension of the council until Pope Julius III reconvened it with the intention to promote a reconciliation of the defeated Lutherans with Charles V.

In 1551, Henri II of France invaded Tuscany and supported Siena in a war against Charles V, while the Duke of Florence supported the Emperor. In addition, France captured the Three Bishoprics of the Holy Roman Empire with the support of Lutherans and formed an alliance with the Ottoman Empire (who had defeated Charles V in Algiers and Budapest in the 1540s) in order to invade Corsica. Charles V responded by forming an alliance with the Kingdom of England and by suspending the reconciliation with the German Lutherans. Florence annexed Siena after a long siege and the victory over the French-Sienese at the Battle of Scannagallo, and the Genoese admiral Andrea Doria recaptured Corsica, but England lost the Pas-de-Calais to France.

Charles V, facing the prospect of a long-lasting alliance between all of his enemies, signed the Peace of Augsburg with the Protestant princes and abdicated by dividing the Habsburg Empire between the Austrian Habsburgs of his brother Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor and the Spanish Habsburgs of his son Philip II of Spain (who inherited all of southern Italy and Milan). War continued between the Habsburgs and France, with the latter being defeated by a Spanish-Imperial army led by Emmanuel Philibert of Savoy (who regained its estates) at the Battle of St. Quentin (1557). Nevertheless, the French recovered and the conflict was prolonged until a compromise was reached at the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis in 1559. The end of the wars allowed Pope Pius IV and Carlo Borromeo to resume the Council of Trent and complete it in 1563, initiating the Catholic Reformation and Baroque period of Italy.

Prelude

Following the Wars in Lombardy between Venice and Milan, which ended in 1454, Northern Italy had been largely at peace during the reigns of Cosimo de' Medici and Lorenzo de' Medici in Florence, with the notable exception of the crisis of 1479-1481 (solved by Lorenzo and followed by the recapture of Otranto from the Ottomans) and the War of Ferrara in 1482–1484.

Charles VIII of France improved relations with other European rulers in the run-up to the First Italian War by negotiating a series of treaties: in 1493, France negotiated the Treaty of Senlis with the Holy Roman Empire; on 19 January 1493, it signed the Treaty of Barcelona with the Crown of Aragon and, later in 1493, the Treaty of Étaples with England.[1][2]

Wars

First Italian War of 1494–1498 or King Charles VIII's War

Ludovico Sforza of Milan, seeking an ally against the Republic of Venice, encouraged Charles VIII of France to invade Italy, using the Angevin claim to the throne of Naples as a pretext. When Ferdinand I of Naples died in 1494, Charles VIII invaded the peninsula with a French Army[3] of twenty-five thousand men (including 8,000 Swiss mercenaries), possibly hoping to use Naples as a base for a crusade against the Ottoman Turks.[4] For several months, French forces moved through Italy virtually unopposed, since the condottieri armies of the Italian city-states were unable to resist them. Charles VIII made triumphant entries into Pisa on November 8, 1494, Florence on November 17, 1494,[5] and Rome on December 31, 1494.[6] Charles VIII found no opposition from Girolamo Savonarola (who established a short-lived theocracy in Florence during the turmoil of the war) and Pope Alexander VI, who let the French King pass through the papal states.[7] Upon seeking the city of Monte San Giovanni in the Kingdom of Naples, Charles VIII sent envoys to the town and the castle located there to seek a surrender of the Neapolitan garrison. The garrison killed and mutilated the envoys and sent the bodies back to the French lines. This enraged the French army so that they reduced the castle in the town with blistering artillery fire on February 9, 1495 and stormed the fort, killing everyone inside.[8] This event was then called the sack of Naples. News of the French Army's sack of Naples provoked a reaction among the city-states of Northern Italy and the League of Venice was formed on March 31, 1495.

The League was specifically formed to resist French aggression. The League was established on 31 March after negotiations by Venice, Milan, Spain and the Holy Roman Empire.[9] Later on the League consisted of the Holy Roman Empire, the Duchy of Milan, Spain, the Papal States, the Republic of Florence, the Duchy of Mantua and the Republic of Venice. This coalition, effectively, cut Charles' army off from returning to France. After establishing a pro-French government in Naples, Charles started to march north on his return to France. However, in the small town of Fornovo he met the League army.

The Battle of Fornovo was fought on July 6, 1495, after an hour the League's army was forced back across the Taro river while the French continued marching to Asti, leaving their carriages and provisions behind.[10] Francesco Guicciardini wrote that both parties strove to present themselves as the victors in that battle, but the eventual consensus was for a French victory, because the French repelled their enemies across the river and succeeded in moving forward, which was their reason for fighting in the first place.[11] In contemporary tradition, though, the battle counted as a Holy League victory, because the French forces had to leave and lost their provisions. To the Italian coalition, however, it was at best a pyrrhic victory, in that its strategic outcome and long-term consequences were unfavorable. Although the League managed to force Charles VIII off the battlefield, it suffered much higher casualties[12] and could not prevent the opposing army crossing the Italian lands as it returned to France.

As a result of Charles VIII's expedition, the regional states of Italy were shown once and for all to be both rich and comparatively weak, which sowed the seeds of the wars to come. In fact, the individual Italian states could not field armies comparable to those of the great feudal monarchies of Europe in numbers and equipment.

Meanwhile, in the Kingdom of Naples, after initial reverses, such as the disastrous defeat by the French at the Battle of Seminara on June 21, 1495, Ferdinand II, King of Naples, with the able assistance of the Spanish general Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba,[13] eventually reduced the French garrison in the Kingdom of Naples. Thus, Charles VIII lost all that he conquered in Italy. King Charles VIII died on April 7, 1498, and was succeeded to the throne of France by his cousin, Louis II, Duke of Orléans, who became Louis XII of France.[14]

Second Italian War or King Louis XII's War (1499–1504)

Ludovico Sforza retained his throne in Milan until 1499, when Charles' successor, Louis XII of France, invaded Lombardy[3] and seized Milan on September 17, 1499.[15] Louis XII justified his claim to the Duchy of Milan by right of his paternal grandfather, Louis duc d'Orléans having married Valentina Visconti in 1387. Valentina Visconti was the heir to the Duchy of Milan in the Visconti dynasty. The marriage contract between Valentina Visconti and Louis, duc d'Orléans, guaranteed that in failure of male heirs, she would inherit the Visconti dominions. However, when the Visconti dynasty died out in 1447, the Milanese ignored the Orleans claim to the Duchy of Milan and re-established Milan as a republic. However, bitter factionalism arose under the new republic which set the stage for Francesco Sforza (father of Ludovico Sforza) to seize control of Milan in 1450.[16]

Louis XII was not the only foreign monarch with dynastic ambitions in the Italian Peninsula. In 1496, while Charles VIII was living in France trying to rebuild his army, Maximilian I of the Holy Roman Empire invaded Italy, to resolve the ongoing war between Florence and Pisa, called the Pisan War.[17] Pisa had been at war almost continually since the early 14th century. In 1406 after a long siege, Pisa fell under the control of the Florentine Republic.[18] When King Charles VIII of France, invaded Italy in 1494, the Pisans rose up against the Florentines and ousted them from Pisa and established Pisa as an independent republic again.[18] When King Charles VIII withdrew from Italy in 1495, the Pisans were not left to fight the Florentines alone. Much of northern Italy was suspicious of the rising power of Florence. Already during 1495, Pisa had received arms and money from the Republic of Genoa. Additionally, the republic of Venice and Milan supported Pisa by sending them cavalry and infantry troops.[19]

This was part of the ongoing conflict between Pisa and Florence that Emperor Maximilian vowed to resolve in 1496. Just as Ludovico Sforza had invited Charles VIII into Italy in 1494, now in 1496, he invited Maximilian I of the Holy Roman Empire into Italy to resolve the conflict between Pisa and Florence.[17] In the conflict between the Florentines and the Pisans, Sforza had favored the Pisans. In the eyes of Maximilian I and the Holy Roman Empire, the Pisan War was causing distractions and divisions within the members of the League of Venice. This was weakening the anti-French League and Maximilian sought to strengthen the unity of League by settling this war. The worst thing that Maximilian feared was more French involvement in Italian affairs. However, Ludovico Sforza invited Maximilian I and the Holy Roman Empire into Italy in order to strengthen his own position.[17] When the Florentines heard about Maximilian's intention of coming to Italy to "settle" Florence's war with Pisa, they were suspicious that the "settlement" would be heavily inclined toward Pisa. Thus, the Florentines rejected any attempted settlement of the war by the Emperor until Pisa was back under Florentine control.[17]

The Florentines knew that another option was open to them. They knew that the French, under their new king—Louis XII—were intent on returning to Italy. Florence chose to take their chances with the French rather than the Holy Roman Empire. They felt that France might help them re-conquer Pisa.[18]

Louis XII was in fact intending to invade Italy to establish his claim over the Duchy of Milan. Louis was also entertaining an ambition to stake a claim to the Kingdom of Naples. This claim was even weaker than Louis XII's claim to Milan. The claim to the Kingdom of Naples was really King Charles VIII's claim. However, Louis demanded recognition of the claim solely because he, Louis, was the successor to Charles VIII.[18] However, Louis was aware of the hostility that was developing among his neighbors, in regards to French ambitions in Italy. Consequently, Louis XII needed to neutralize some of this hostility. Accordingly, in August 1498, Louis XII signed a treaty with Archduke Philip, son of Maximilian I, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire which secured the borders between the Holy Roman Empire and France.[20] In July 1498, Louis renewed the Treaty of Étaples of 1492 with Henry VII of England. In August 1498, the Treaty of Marcoussis was signed between Louis XII and Ferdinand and Isabel. This Treaty resolved none of the outstanding territorial disputes between Spain and France, but agreed that both Spain and France "have all enemies in common except the Pope."[21]

In July 1499, the French Army left Lyon and invaded Italy with 27,000 men (10,000 of which were cavalry and 5,000 of which were Swiss mercenaries). Louis XII placed Gian Giacomo Trivulzio in command of his army. In August 1499, the French Army came across Rocca di Arazzo, the first of a series of fortified towns in the western part of the Duchy of Milan.[22] Once the French artillery batteries were in place, it took only five hours to open a breach in the walls of the town. After conquering the town, Louis ordered that the garrison and part of the civil population be executed in an attempt to instill fear in his enemies, crush their morale and encourage the quick surrender of the other strongholds in western Milan.[22] The strategy was a success and the campaign for the duchy of Milan ended swiftly. On September 5, 1499, terms were negotiated for the surrender of the city of Milan and on October 6, 1499, Louis made his triumphant entry into Milan.[15]

Once Louis XII was installed in Milan, he came under real pressure from the Florentines to assist them in re-conquering Pisa. King Louis and his advisors were annoyed at what they considered to be an arrogant request by the Florentines, since in their recent struggle to conquer Milan, the Florentines had maintained strict neutrality despite their long record of pro-French diplomacy.[18] However, Louis was mindful that if he were to conquer Naples, he must cross Florentine territory on the road to Naples. Louis XII needed good relations with Florence. So finally, on June 29, 1500, a combined French and Florentine army laid siege to Pisa. Within a day French guns had knocked down 100 feet of the city walls Pisa. An assault was made at the breach, but the French were surprised by the strong resistance thrown up by the Pisans. The French Army was forced to break off the siege on July 11, 1500, and retreat to the north.[23]

As part of Louis XII's continuing attempt to pacify or neutralize his neighbors to prevent them from obstructing his ambitions in Italy, Louis XII opened discussions with King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain. On November 11, 1500, Louis signed the Treaty of Grenada.[24] The Treaty of Grenada memorialized Louis XII's agreement with Ferdinand II of Aragon, King of Spain, to divide the Kingdom of Naples between themselves. Then Louis set off marching south from Milan towards Naples. King Louis XII's agreement with Spain was heavily criticized by contemporaries—including Niccolò Machiavelli in his masterpiece The Prince. Modern historians also criticize the Treaty of Grenada by calling it "foolish" on Louis XII's part. They allege, as does Machiavelli, that Louis XII did not need to invite Spain into Italy. Louis XII had achieved everything he needed in the Treaty of Marcoussis, that he had signed two years earlier. The Treaty of Grenada did nothing but bind Louis XII's own hands. Once involved in Italian affairs, Spain would work to the detriment of France in Italy. Indeed, this is just what happened.

By 1500, a combined French and Spanish force had seized control of the Kingdom of Naples.[25] Louis XII appointed Louis d'Armagnac, Duke of Nemours as viceroy at Naples. On October 12, 1501,[26] the new viceroy took over administration of Naples. However, the new French viceroy proved to be more concerned with extending the French share of the kingdom than he was in ensuring that the Spanish received their share. This did much to aggravate relations between France and Spain.[26] These disagreements about the terms of the partition led to a war between Louis and Ferdinand. By 1503 Louis, having been defeated at the Battle of Cerignola on April 28, 1503,[27] and Battle of Garigliano on December 29, 1503,[28] was forced to withdraw from Naples, which was left under the control of a Spanish viceroy, General Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba.

War of the League of Cambrai (1508–1516)

Julius II was elected pope following the death of the short-lived Pius III on 18 October 1503.[29] He was extremely concerned about the territorial expansion of the Republic of Venice in northern Italy. Pope Julius was not alone in his fear of Venetian territorial ambitions. Being from Genoa, Pope Julius knew of the Genoese hatred of Venice for forcing the other states out of the rich Po Valley as the Republic expanded its frontiers across northern Italy.[29] Additionally, Emperor Maximilian was upset with the Venetian seizure of Duchy of Friuli and its claim on the bordering County of Gorizia, which Maximilan had taken over in 1500 after the exctinction of the House of Gorizia.[29] Furthermore, King Louis XII of France had been firmly established in Milan since 1500. Louis XII now saw Venice as a threat to his position in Milan. Moreover, King Ferdinand of Naples (and of Aragon) resented the fact that Venice held a number of towns in southern Italy along the Adriatic coast.

The circumstances were set for Pope Julius to form the League of Cambrai on December 10, 1508, in which France,[30] the Papacy, Spain, the Duchy of Ferrara and the Holy Roman Empire agreed to restrain the Venetians.[31] Although the League destroyed much of the Venetian army at the Battle of Agnadello on May 14, 1509,[32] it failed to capture Padua.[33]

By 1510, relations between Louis XII and the pope had broken down. Accordingly, the Pope changed sides in the war and allied itself with Venice, which was now less of a threat to the pope due to previous Venetian defeats. In March 1510, Pope Julius brokered a deal with the Swiss Cantons that brought 6,000 more Swiss troops into the war against the French. Following a year of fighting over the Romagna, during which the Veneto-Papal alliance was repeatedly defeated, the Pope proclaimed a Holy League against the French in October 1511.[34] This league rapidly grew to include England, Spain, and the Holy Roman Empire.

French forces under Gaston de Foix inflicted an overwhelming defeat on a Spanish army at the Battle of Ravenna on April 11, 1512.[35] Foix was killed and the French were forced to withdraw from Italy when the Swiss invaded and conquered Milan.[36] The Swiss reinstated Massimiliano Sforza to the ducal throne of Milan.[37] However, the victorious Holy League fell apart over the subject of dividing the spoils, and in March 1513 Venice allied with France, agreeing to partition Lombardy between them.[38]

Louis mounted another invasion of Milan but was defeated at the Battle of Novara on June 6, 1513. The Battle of Novara would be the last in which the traditional Swiss tactic of charging in three columns would be used with success.[39] The victory of the Holy League at Novara was quickly followed by a series of Holy League victories against the Venetians at La Motta on October 7, 1513, the French at Guinegate on August 16, 1513, and the Scots at Flodden Field on September 9, 1513.

Overshadowing all, however, was the death of Pope Julius II on February 20, 1513,[38] which left the League without effective leadership. On January 1, 1515, Louis XII also died[40] and was succeeded to the throne of France by his nephew, Francis I. Francis I continued Louis XII's war against the League of Cambrai in Italy by leading a French and Venetian Army against the Swiss and routing them at Marignano on September 13–14, 1515.[41] This victory decisively broke the string of victories that the Swiss had enjoyed against the Venetians and the French. Following the Battle of Marignano, the League of Cambrai or Holy League collapsed as both Spain and the new Pope, Leo X, gave up on the notion of placing Massiliano Sforza on the ducal throne of Milan.[42] By the treaties of Noyon on August 13, 1516, and Brussels, the entirety of northern Italy was surrendered to France and Venice by Maximilian I.

Italian War of 1521–1526

On 28 June 1519, the German princes elected Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor to succeed his grandfather Maximilian I. Charles was already Prince of the Habsburg Netherlands since 1506, King of Habsburg Spain since 1516, and Archduke of the Habsburg Monarchy since 1519. All the territories surrounding France were now under the rule of Charles V, forming the so-called Habsburg ring. Furthermore, Francis I himself had been a candidate for election as Holy Roman Emperor before Charles V was chosen. This led to a personal rivalry between Francis I and Charles V that was to become one of the fundamental conflicts of the sixteenth century.[43]

The deterioration of relations between the Habsburgs and Francis I provided Francis I with a pretext for war with Charles. Francis' candidacy for Emperor had been supported by Pope Leo X. However, just when Francis I began to count on the support of Pope Leo in a war against Charles V, Pope Leo suddenly made peace with the Emperor and sided with the Holy Roman Empire against France. Then to make matters worse, Henry VIII of England joined the pope (Pope Leo X died in 1522 and was replaced by Adrian VI who died in 1523 and was succeeded by Clement VII) and the emperor in their war on France.

The papal-imperial army led by Prospero Colonna and the Marquis of Pescara took Milan from the French in 1521 and returned it to Francesco Sforza, the Duke of Milan, in 1522.[44] The French were outmatched by the Imperial-Spanish arquebusier tactics and suffered crippling defeats at Bicocca on April 27, 1522,[45] and Sesia, against Imperial-Spanish troops on April 30, 1524. With Milan in Imperial hands, Francis personally led a French army into Lombardy in 1525, only to be utterly defeated and captured at the Battle of Pavia on February 24, 1525.[46] With Francis imprisoned in Spain, a series of diplomatic maneuvers centered around his release ensued, including a special French mission sent by Francis' mother Louise of Savoy to the court of Suleiman the Magnificent that would result in an Ottoman ultimatum to Charles – an unprecedented alliance between Christian and Muslim monarchs that would cause a scandal in the Christian world. Suleiman used the opportunity to invade Hungary in the summer of 1526, defeating Charles' allies at the Battle of Mohács on August 29, 1526. Despite all these efforts, Francis was required to sign the Treaty of Madrid in January 1526,[47] in which he surrendered his claims to Italy, Flanders, and Burgundy in order to be released from prison.

War of the League of Cognac (1526–1530)

In 1526, Pope Clement VII, alarmed at the growing power of the Empire, formed the League of Cognac against Charles V on May 22, 1526.[47] Members of the League were the Papal States under Pope Clement VII, France under King Francis I,[48] England under Henry VIII, the Republic of Venice, Republic of Florence, and the Duchy of Milan.

The League planned a war against the Empire to begin in early 1526. The Imperial troops in Italy were extremely discontented because they were owed so much back pay that was not forthcoming. In some places in Italy, the Imperial troops were even refusing to take the field of battle until they were paid.[49] The military commanders of the League of Cognac wished to take advantage of this disorder and demoralization of the Imperial troops and to attack the troops in early 1526.[49] However, the League commanders knew that they were soon to be joined by some Swiss mercenaries they had hired. So they delayed the start of the attack until they were joined by the Swiss.

Meanwhile, Venetian troops under the Duke of Urbino were marching westward across northern Italy to join their allies, the Papal troops. Along the way, they discovered that a revolt had occurred in Lodi, a town under the rule of the Visconti family. A disaffected Italian infantry captain from Lodi was willing to open the gates of the town to the Venetian Army. Consequently, the Venetians were able to quickly occupy Lodi on June 24, 1526.[49]

Another revolt broke out in the city of Milan against the rule of Francesco Sforza. Milan had been bouncing back and forth between control by the Sforza family and control by the Kingdom of France since 1499, when Ludovico Sforza was driven out of Milan by the French King Louis XII. Except for two months in early 1500, Milan had remained under the control of the French for twelve years. In 1512, however, political control of Milan shifted back to the Sforza family—under Massimiliano Sforza—for three years until King Francis I of France was able to drive out the Sforzas once more. Milan was again under French rule for another six years before Francesco Sforza kicked the French out in November 1521. Francis I returned to Milan and restored French control in the city in October 1524 only to lose it again in February 1525 in the Treaty of Madrid, which had been forced on him by Emperor Charles V. One of Francis's first goals in joining the League of Cognac was to repudiate the Treaty of Madrid and regain control over Milan. However, French troops had not yet entered into the new war in Italy and their agreement to do so remained secret.

The uprising in Milan in the summer of 1526 was coordinated with the defenders of the "Castello" in Milan. The populace was upset over the behavior of the troops in the garrison of the Castello while they were on leave in town.[49]

In June 1526, Hugo of Moncada, the commander of Imperial forces in Italy, was sent as an ambassador from the Emperor to Pope Clement VII in the Vatican.[49] His message from the Emperor was that if the Papal States aligned themselves with the French in the current war, the Holy Roman Empire would seek to use both the Italian towns of Colonna and Siena against the papacy. Pope Clement VII recognized the threat these two cities presented to the Papal States should they join forces with the Imperial troops already in Italy. Accordingly, the pope withdrew his forces at just the time the French forces entered Lombardy in northern Italy.[49]

Suddenly the League started to fall apart. Venice had suffered devastating damage in the Italian Wars. Its subject lands—the "Terraferma"—had been ravaged from 1509 to 1516. At one time or another during the Italian Wars, every city in Venice's Terraferma, except for the city of Treviso, had been lost to an enemy.[50] As a result, Venice refused to contribute any more troops to the war effort. After 1529, Venice would cease all direct involvement in the Italian Wars.[50] Realizing that their goal of reconquering Milan was no longer on the table, the French army left Lombardy and headed back to France. With the withdrawal of French forces from Lombardy, mutinous imperial troops of Lutheran faith (who were owed massive back pay) decided to sack Rome (1527) and imprison Clement who had taken refuge in the Castel Sant'Angelo.[51] With the conclusion of the Treaty of Cambrai (also known as "Peace of the Ladies" because it was negotiated by Luisa of Savoy for France and Margareth of Austria for the Holy Roman Empire) in 1529, which formally removed Francis from the war, the League collapsed; Venice made peace with Charles V, while Florence was placed again under the Medici.

When the Treaty of Cambrai was being signed in August 1529,[52] thus ending the War of the League of Cognac, Emperor Charles V was already making his way to Italy.[53] This trip to Italy and the settlement of Italian affairs during the trip is traditionally viewed as marking the end of Italian political liberty and independence and the beginning of a long period of control[53] by Charles V. At the Congress of Bologna (1530), Charles V obtained the medieval title of King of Italy. The Medici, ousted during the war, was restored as the dynastic family of Florence.[54]

Italian War of 1536–1538

Thus, this third war between Charles V and King Francis I of France[48] began with the death of Francesco Sforza, the Duke of Milan during the night of November 1–2, 1535.[55] Upon his death, Francesco Sforza left no heirs. Emperor Charles V was on another trip to Italy when he heard about the death of Sforza.[56] When the representatives of Emperor Charles V took charge of the Duchy of Milan upon the death of Sforza, there were no protests or uprisings among the people of Milan.[57] Nor were there any objections from any other Italian states. There were, however, objections from France. Francis I, king of France, firmly believed that Asti, Genoa and the Duchy of Milan were all rightfully his.[58] Thus recovering Milan for France remained the primary goal for Francis I. So when Charles directly annexed the Duchy of Milan, King Francis I of France invaded Italy. At about this time, Francis told his council that he had allowed Emperor Charles V to become too strong in Italy.

In 1536, a new congress was held in Rome between Charles V and Pope Paul II with the latter asking for peace in Italy and the first expecting the call for the ecumenical council to deal with Lutheranism. In late March 1536, a French army under the command of Philippe de Chabot, seigneur de Brion advanced into Piedmont with 24,000 infantry and 3,000 horse.[59] The French Army captured and entered Turin in early April 1536, but failed to take Milan. Meanwhile, the pro-French section of the population in the city of Asti rose up against and overthrew their Imperial occupiers.[56]

In response to the capture of Turin by the French, Charles V invaded Provence, advancing to Aix-en-Provence. Charles took Aix on August 13, 1536, but could go no further because the French Army blocked all roads leading to Marseilles.[60] Consequently, Charles withdrew back to Spain rather than attacking the heavily fortified town of Avignon.

Charles V's fruitless expedition to Provence distracted his attention from events in Italy. French troops operating in the Piedmont were joined by 10,000 Italian infantry and a few hundred horses on a march to Genoa.[60] These Italian troops had been raised by Guido Rangoni, Galeotto Pico Della Mirandola and other members of the military nobility of southern Lombardy. Galeotto had gained control of Mirandola in 1533 by killing his uncle Giovanni Francesco Pico Della Mirandola.[60] In preparation for his invasion of Italy, Francis I's ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Jean de La Forêt, obtained, in early 1536, a treaty of alliance between the Ottoman Empire and France. By the end of 1536, an Ottoman fleet was poised off the coast of Genoa ready to strike in coordination with the land forces marching toward Genoa. However, when the land forces arrived before Genoa in August 1536, they found that the garrison at Genoa had recently been reinforced.[60] Furthermore, an expected uprising among Fregoso partisans in Genoa did not materialize. So the land forces moved by Genoa and marched on into the Piedmont where they captured and occupied Carignano along with three other towns between Turin and Saluzzo: Pinerolo, Chieri and Carmagnola. The active participation of the Ottomans in the war was not significant, but their very entry into the war had a curbing effect on the actions of Charles V. Fighting a two-front war, against the Ottomans in the east and the French in the west did not appeal to Charles V. Consequently, by 1538, Charles was ready for peace.

The Truce of Nice, signed on June 18, 1538, ended the war, leaving Turin in French hands but effecting no significant changes to the map of Italy.[61]

Italian War of 1542–1546

Francis I, King of France, allied himself once more with Suleiman I of the Ottoman Empire and on July 12, 1542, declared war on the Holy Roman Empire.[62] Francis I launched his final invasion of Italy against the town of Perpignan. A Franco-Ottoman fleet under the command of Ottoman admiral Hayreddin Barbarossa captured the city of Nice on August 22, 1543,[62] and laid siege to the citadel. The defenders of the citadel were relieved within a month. For Christian and Islamic troops to act in coordination to attack a Christian town was regarded as shocking. Thus, in this attack on Nice, King Francis needed to play down the role of the Ottoman Turks.[63] However, Francis I did something even more scandalous when he turned the French naval port of Toulon over to Barbarossa to use as winter quarters for the Ottoman fleet.[63]

Once again Milan was the pretext for the War of 1542–1546.[48] The French Army commanded by François de Bourbon, Count d'Enghien defeated an Imperial army at the Battle of Ceresole on April 14, 1544.[63] However the French failed to penetrate further into Lombardy.

On January 6, 1537, Alessandro de Medici, the Duke of Florence, was assassinated by his distant cousin, Lorenzino de' Medici.[64] Alessandro had the support of the Holy Roman Empire as he was married to Charles V's daughter, Margaret. With the Duke of Florence removed, some citizens of Florence attempted to establish a republic in the city, while other pro-Medici citizens sought to install the seventeen-year-old Cosimo de' Medici as the new Duke. The republican faction raised an army[65], while the pro-Medici faction sought assistance from Charles V. King Francis I supported the now-exiled republican faction as a means of preventing Charles V from taking over Florence.[64] On June 4, 1544, the army of republican exiles from Florence under the command of Piero Strozzi was defeated by an Imperial army under the command of Philippe de Lannoy and Ferrante da Sanseverino, Principe di Salerno.

Charles V and Henry VIII of England then proceeded to invade northern France, seizing Boulogne and Soissons.[48] At one point the English and Imperial troops were within sixty miles of Paris.[48] A lack of cooperation between the Germanic-Spanish and English armies, coupled with increasingly aggressive Ottoman attacks, led Charles to abandon these conquests, restoring the status quo once again.

Italian War of 1551–1559

On March 31, 1547, King Francis I died and was succeeded by his son, Henry II of France.[48] In 1551, Henry II declared war against Charles with the intent of recapturing Italy and ensuring French, rather than Habsburg, the domination of European affairs. An early French offensive against Lorraine was successful, but the attempted French invasion of Tuscany was stopped in 1553. The French were decisively defeated at the Battle of Marciano on August 2, 1554. Nonetheless, as a result of this war, France obtained three French-speaking cities: Metz, Toul and Verdun.[66] Furthermore, the alliance with the Ottomans had reached its peak under Henri II of France with the Invasion of Corsica (1553)

In 1556, during the course of the war, Charles V abdicated the Imperial throne as well as the throne of Spain. He abdicated the Imperial throne of the Holy Roman Empire to his brother, who became Ferdinand I of the Holy Roman Empire. The throne of Spain went to Charles' son, who became Philip II of Spain. Thus, the abdication of Charles V split the Habsburg empire that had surrounded France. From this point on, Spain and the Holy Roman Empire would no longer act in absolute coordination as they had under the personal union of Charles V. Gradually, the two Habsburg entities would drift off separately in their own directions following their own divergent interests.

At this point the focus of the war shifted away from Italy and toward Flanders, where Philip, in conjunction with Emmanuel Philibert of Savoy, decisively defeated the French at St. Quentin on August 10, 1557.[67] Following the defeat at St. Quentin, the French did recover and took some new initiatives in the war. England's entry into the war in 1557 led to the French capture of Calais in January 1558.[68] Furthermore, France plundered Habsburg positions in the Netherlands. The wars ended with the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis, which was signed on April 3, 1559.[69]

The Peace of Cateau-Cambrèsis (1559) involved delegates from France, Spain, England, and the Holy Roman Empire.[70] The general clause of the Peace made the participants recognize the results of the last eight years of war.[71] Besides ending the war, Henri II of France and Philip II of Spain agreed in the treaty to ask the Pope to recognize Ferdinand as Holy Roman Emperor and to reconvene the Council of Trent.[72][73]

Aftermath and impact

.png)

The European balance of power changed significantly during the Italian Wars. The affirmation of French power in Italy around 1494 brought Austria and Spain to join an anti-French league that formed the "Habsburg ring" around France (Low Countries, Aragon, Castile, Empire) via dynastic marriages that eventually led to the large inheritance of Charles V. [74] On the other hand, the last Italian war ended with the division of the Habsburg Empire between the Spanish and Austrian Habsburgs following the abdication of Charles V. Philip II of Spain was heir of the kingdoms held by Charles V in Spain, southern Italy, and South America. Ferdinand I was the successor of Charles V in the Holy Roman Empire extending from Germany to northern Italy and became suo jure king of the Habsburg Monarchy. The Habsburg Netherlands and the Duchy of Milan were left in personal union to the King of Spain while continuing to be part of the Holy Roman Empire.

The division of the empire of Charles V, along with the expansion of the French state over the Pas-de-Calais and the Three Bishoprics, was a positive result for France. However, the Habsburgs had gained a position of primacy in Europe and Italy at the expense of the French Valois. In fact, in order to achieve this defensive objective, France was forced to end opposition to Habsburg power and abandon its claims in Italy. Henri II also restored the Savoyard state to Emmanuel Philibert, who settled in Piedmont, and Corsica to the Republic of Genoa. For this reason, the conclusion of the Italian Wars for France is considered to be a mixed result.

At the end of the wars, Italy was largely divided between viceroyalties of the Spanish Habsburgs in the south and formal fiefs of the Austrian Habsburgs in the north.[75] The most significant Italian power left was the Papacy in central Italy, as it maintained major cultural and political influence during the Catholic Reformation. The Council of Trent, suspended during the war, was reconvened by the terms of the peace treaties and came to an end in 1563.

Interpretations of the results

As in the case of France, the Habsburg result is also variously interpreted. Many works of the 20th century, such as those of Eric Cochrane and Manuel F. Alvarez, individuated in the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis the beginning of Spanish hegemony in Italy. According to that view, the partition of the Habsburg empire at the abdication of Charles V left the position of the Holy Roman Empire in Italy weakened in favor of Spain so that the peace was mostly a victory of the latter. However, in 21st-century historiography there is a reconsideration of the topic. Christine Shaw in her revised "Italian Wars (1494-1559)", one of the most complete works on the subject, Micheal J. Levin in "Agents of Empire", and William Reger in "Limits of Empire", reject the concept of a Spanish hegemony on the ground that too many limits prevented Spain's dominance in the peninsula, and maintain that other powers also held major influence in Italy after 1559.

According to Christine Shaw, it was the dual protection of Spain and the Holy Roman Empire that was established in Italy after Cateau-Cambrésis. Among Italian historians, a similar view was held by Salvatore Puglisi (in "le prime strette dell'Austria in Italia"), who understood the result of the wars as the beginning of both Austrian and Spanish Habsburg power in Italy. According to Angelantonio Spagnoletti in his "Principi Italiani e Spagna nell'età barocca", echoing Benedetto Croce in his works on Baroque Italy, the Papacy and Spain emerged as the two main forces in the peninsula after Cateau-Cambrésis. According to their view, the position of the Papacy was strengthened by the conclusion of the council of Trent and the beginning of the counter-reformation. Peter J. Wilson writes that three overlapping and competing feudal networks, Imperial, Spanish, and Papal, were affirmed in Italy as a result of the end of the wars. Terms such as "refeudalization" (rifeudalizzazione) have also been used by Italian authors to describe the political and socio-economic situation of Italy after 1559.[76][77][78]

In the long-term, Habsburg primacy in Italy continued to exist, but it varied significantly due to the change of dynasties in Austria and Spain. Following the European wars of succession, the Habsburg-Lorraine of Austria gained direct or indirect control of the fiefs of Imperial Italy, whereas the south passed to a cadet branch of the Spanish Bourbons. France would return in Italy to confront Habsburg power, first under Louis XIV, and later under Napoleon, but only the unification of Italy will permanently remove foreign powers from the peninsula.

Celebrations

In France, Henry II was fatally wounded on 10 July 1559, in a joust held during the celebrations of the peace. His death led to the accession of his 15-year-old son Francis II, who in turn died on 5 December 1560. The French monarchy was thrown into turmoil, which increased further with the outbreak of the French Wars of Religion in 1562.

Art

The Italian Wars had a number of consequences for the work and workplace of Leonardo da Vinci. He had planned a large horse statue, "Gran Cavallo", in 1495, but the seventy tons of bronze intended for the statue was instead cast into weapons to save Milan. Later, following a chance encounter with Francis I after the Battle of Marignano, Leonardo agreed to move to France and bring along his masterpiece Mona Lisa, which has remained in France to this day. Leonardo spent his final years in France in a house provided by Francis I.

Military

The Italian Wars represented a revolution in military technology and tactics—some historians consider these wars the dividing point between modern and medieval times.[79] Contemporaneous historian Francesco Guicciardini wrote of the initial 1494 French invasion:

Now owing to this invasion of the French everything was turned upside down in a sudden storm…sudden and violent wars broke out, ending with the conquest of a state in less time than it used to take to occupy a villa. The siege and taking of a city became extremely rapid and achieved not in month but in days and hours.[80]

Infantry

Infantry underwent profound developments during the Italian Wars, evolving from a primary pike- and halberd-wielding force to a more flexible arrangement of arquebusiers, pikemen, and other troops. While landsknechts and Swiss mercenaries continued to dominate during the early part of the wars, the Italian War of 1521 demonstrated the power of massed firearms in pike and shot formations.

A 1503 skirmish between French and Spanish forces first demonstrated the utility of arquebuses in battle. The Spanish general, Gonzalo de Codoba, faked a retreat, luring a contingent of French men-at-arms between two groups of his arquebusiers. As the French army stepped between the marksmen, volleys of bullets battered them on both flanks. Before the French could attack the vulnerable arquebusiers, a Spanish cavalry charge broke the French forces and forced their retreat. While the French army escaped, the Spanish inflicted severe casualties.[81]

So successful was the employment of firearms in the Italian Wars that Niccolò Machiavelli, often characterized as an enemy of the use of the arquebus, wrote in his treatise on The Art of War that all citizens in a city should know how to fire a gun.[82]

Veterans turned conquistadors

Various Spanish soldiers who participated in the Italian Wars emigrated to the Americas and turned into conquistadors there.[83][84] Experience in the Italian Wars was a decisive factor when organizing squadrons of conquistadors in the Americas.[83] However chronicler Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo reacted against Spanish conquistadors who boasted a background in the Italian Wars, writing that any veteran in the Americas must have "failed to become rich, and if he was once rich, he must have gambled the riches away or [somehow] lost them".[83] Fernández de Oviedo also claimed the Italian Wars were fought in more comfortable conditions than conflicts in the Americas.[83] Francisco Sebastián in Hernando de Sotos expedition through southwestern North America, was a veteran from the Italian Wars. He noted that conditions of warfare in America were harsher than in Italy because no plunder of value could be obtained from "naked" Indians with bow and arrows.[83]

Francisco de Carvajal and Pedro de Valdivia fought in the Battle of Pavia and were present at the Sack of Rome. Carvajal who was older than Valdivia had also fought in the Battle of Ravenna in 1512.[84] These soldiers met again in Peru as they aided the Pizarro brothers to defeat Diego de Almagro in 1538. Francisco de Carvajal stayed in Peru going further to aid the Pizarro brothers in their wars against rival Spanish factions,[83] Valdivia instead marched south starting the conquest of Chile and ignited the Arauco War against native Mapuche. In the Battle of Jaquijahuana (1548) the two met again but this time on opposite sides, with Carvajal being defeated. They were the only veterans of the Italian Wars in the battle as the other Spanish present only had military experience from the Americas.[83] Valdivia was eventually defeated and killed himself at the Battle of Tucapel, 1553. Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar also had a stint in the Italian Wars before conquering Cuba.[84] Among the men who participated in Hernán Cortés conquest of Mexico there were veterans of the Italian Wars who instructed others on the use of cannons.[83]

Cavalry

Heavy cavalry—the final evolution of the fully armored medieval knight—remained major players on the battlefields of the Italian Wars. Here, the French gendarmes were generally successful against heavy mounted troops from other states, owing significantly to their excellent horses, but on the contrary, they turned out to be very vulnerable to the pikermen. The Spanish besides using heavy cavalry also used light cavalry (called Jinetes) for skirmishing.

Artillery

Artillery, particularly field artillery, became an indispensable part of any first-rate army during the Italian Wars. During his invasion of Italy, Charles VIII employed the first truly mobile siege train: culverins and bombards mounted on wheeled carriages, which could be deployed against an enemy stronghold immediately after arrival. The French siege arsenal brought with it multiple technological innovations. Charles' army pulled cannons with horses rather than the oxen typically used at the time.[85] Additionally, French cannons, made using methods used to cast bronze church bells, achieved a lightness and mobility previously unheard of.[86] Perhaps the most important improvement the French made to cannons, however, was the creation of the iron cannonball. Before the Italian Wars, artillery fired stone balls that often shattered on impact.[86] The invention of the watermill allowed furnaces to generate enough heat to melt the iron to be smelted into cannonballs.[87] With this technology, Charles’ army could level, in a matter of hours, castles that had formerly resisted sieges for months and years.[79]

Military leadership

The armies of the Italian Wars were commanded by a wide variety of leaders, from mercenaries and condottieri to nobles and kings.

Fortification

Much of the fighting during the Italian Wars took place during sieges. Successive invasions forced Italy to adopt increasing levels of fortification, using such new developments as detached bastions that could withstand sustained artillery fire.

Historiography

The Italian Wars are one of the first major conflicts for which extensive contemporary accounts from people involved in the wars are available, owing largely to the presence of literate, and often extremely-well educated, commanders. The invention of modern printing, still less than one century old, undoubtedly played a large role in the memorialization of the conflict as well. Major historians of the period include Francesco Guicciardini and Paolo Sarpi.

Nomenclature

The naming of the component conflicts within the Italian Wars has never been standardized and varies among historians of the period. Some wars may be split or combined differently, causing ordinal numbering systems to be inconsistent among different sources. The wars may be referred to by their dates or by the monarchs fighting them. Usually, the Italian Wars are grouped into three major phases: 1494-1516; 1521-1530; and 1535-1559.

Contemporary accounts

A major contemporary account for the early portion of the Italian Wars is Francesco Guicciardini's Storia d'Italia (History of Italy), written during the conflict and advantaged by the access that Guicciardini had to papal affairs.

Citations

- Lessafer, Peace Treaties and International Law in European History: From the Late Middle Ages to World War One, 23.

- Morris, Europe and England in the Sixteenth Century, 150.

- Albert Guérard, France: A Modern History (Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1959) p. 132.

- R. Ritchie, Historical Atlas of the Renaissance, 64

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559 (Harlow, England: Pearson Education Limited, 2012) p. 22.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, pp.23–24.

- Alexander VI, Treccani encyclopedia

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 25.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 27.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, 31.

-

But the victory was universally adjudged to the French on account of the great Disproportion of the slain, of their driving the Enemy on the other side of the River, and because their Passage was no longer obstructed, which was all they contended for, the Battle being fought on no other Account.

— Francesco Guicciardini, The history of Italy, 1753, pp. 338–339 (Storia de Italia, Bk. II, 9) - https://web.archive.org/web/20070206025953/http://www.deremilitari.org/, accessed 22nd March 2014

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 32.

- Frederic J. Baumgartner, Louis XII (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1996) pp. 51–53.

- Frederic J. Baumgartner, Louis XII, p. 114.

- Frederic J. Baumgartner, Louis XII, p. 40.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 39.

- Frederic J. Baumgartner, Louis XII, p. 119.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 41.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, the Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 43.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 44.

- Frederic J. Baumgartner, Louis XII, p. 113.

- Frederic J. Baumgartner, Louis XII, p. 120.

- Frederic J. Baumgartner, Louis XII, p. 122.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, pp. 60–61.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 61.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, pp. 64–65.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, pp. 68–69.

- Henry S. Lucas, The Renaissance and the Reformation (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1960) p. 329.

- Albert Guérard, France: A Modern History, p. 129

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 87.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 89.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 95.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 103.

- Frederic J. Baumgartner, Louis XII pp. 220–221.

- Frederic J. Baumgartner, Louis XII, p. 221.

- Frederic J. Baumgartner, Louis XII, p. 223.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 120.

- Frederic J. Baumgartner, Louis XII, p. 230.

- Frederic J. Baumgartner, Louis XII, p. 243.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, pp. 128–129.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 131.

- Rhea Marsh Smith, Spain: A Modern History (Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1965) p. 145.

- Albert Guérard, France: A Modern History, pp. 134–135.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, pp. 143–144.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, pp. 150–152.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 155.

- Albert Guérard, France: A Modern History, p. 135.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 156.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 293.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, pp. 160–164.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 169.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 218.

- Congress of Bologna, Treccani encyclopedia

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 229.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 231.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, pp. 229–230.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 228.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 230.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 233.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 237.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 238.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 240.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 234.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 242.

- Albert Guérard, France: A Modern History, p. 136.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 278.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 282 and Eric Durot, François de Lorraine (Paris, 2012), chapters 7 and 8.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 283.

- Treccani encyclopedia

- Treccani encyclopedia

- Setton, Kenneth Meyer (1984). The Papacy and the Levant, 1204-1571. ISBN 9780871691620.

- Paolo Sarpi, Istoria del Concilio Tridentino, Book 5. Ferdinand became Emperor in 1556 after the abdication of Charles V, but the Pope refused to recognize him until he was requested to do so by Spain and France following the Peace of 1559.

- "The Book of Dates; Or, Treasury of Universal Reference: ... New and Revised Edition". 1866.

- Legacies of the Italian Wars(in Italian)

- Linde, Luis M. (2005). Don Pedro Girón, duque de Osuna: la hegemonía española en Europa a comienzos del siglo XVII. Encuentro. p.136. ISBN 9788474907629.

- Max Boot, War Made New: Technology, Warfare, and the Course of History, 1500 to Today (New York: Penguin Group Inc., 2006), 4–5.

- Francesco Guicciardini, The History of Florence, trans. Cecil Grayson (New York: Twayne Publishers Inc., 1964), 20.

- Hans Delbrück, The Dawn of Modern Warfare, vol. 5 of History of the Art of War (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 40.

- Niccolò Machiavelli, The Art of War, trans. Christopher Lynch (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 44–45.

- Espino López, Antonio (2012). "El uso táctico de las armas de fuego en las guerras civiles peruanas (1538–1547)". Historica (in Spanish). XXXVI (2): 7–48.

- Rosenblat, Angel; Tejera, María Josefina (2002). El español de América (in Spanish). Biblioteca Ayacucho. p. 69. ISBN 980-276-351-9.

- Guicciardini, Francesco (1984). The history of Italy. Translated by Alexander, Sydney. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-691-00800-4. OCLC 10146515.

- Max Boot, War Made New: Technology, Warfare, and the Course of History, 1500 to Today (New York: Penguin Group Inc., 2006), 4.

- Hans Delbrück, The Dawn of Modern Warfare, vol. 5 of History of the Art of War (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 34.

Bibliography

- Arfaioli, Maurizio. The Black Bands of Giovanni: Infantry and Diplomacy During the Italian Wars (1526–1528). Pisa: Pisa University Press, Edizioni Plus, 2005. ISBN 88-8492-231-3.

- Arnold, Thomas F. The Renaissance at War. Smithsonian History of Warfare, edited by John Keegan. New York: Smithsonian Books / Collins, 2006. ISBN 0-06-089195-5.

- Baumgartner, Frederic J. Louis XII. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1994. ISBN 0-312-12072-9.

- Black, Jeremy. "Dynasty Forged by Fire." MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History 18, no. 3 (Spring 2006): 34–43. ISSN 1040-5992.

- ———. European Warfare, 1494–1660. Warfare and History, edited by Jeremy Black. London: Routledge, 2002. ISBN 0-415-27532-6.

- Blockmans, Wim. Emperor Charles V, 1500–1558. Translated by Isola van den Hoven-Vardon. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-340-73110-9.

- Fraser, Antonia, Mary Queen of Scots (New York: Delacorte Press, 1969).

- Guérard, Albert, France: A Modern History (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1959). ISBN 978-0-582-05758-6.

- Guicciardini, Francesco. The History of Italy. Translated by Austin Parke Goddard. London: John Towers. 1753.

- Guicciardini, Francesco. The History of Italy. Translated by Sydney Alexander. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984. ISBN 0-691-00800-0.

- Hall, Bert S. Weapons and Warfare in Renaissance Europe: Gunpowder, Technology, and Tactics. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-8018-5531-4.

- Knecht, Robert J. Renaissance Warrior and Patron: The Reign of Francis I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-521-57885-X.

- Konstam, Angus. Pavia 1525: The Climax of the Italian Wars. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 1996. ISBN 1-85532-504-7.

- Lesaffer, Randall. Peace Treaties and International Law in European History: From the Late Middle Ages to World War One. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-521-82724-9.

- Lucas, Henry S., The Renaissance and the Reformation (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1960).

- Mallett, Michael and Shaw, Christine, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559 (Harlow, England: Pearson Education, Inc., 2012). ISBN 978-0-582-05758-6.

- Morris, T.A. Europe and England in the Sixteenth Century. London: Routledge, 2002. ISBN 0-203-01463-4.

- Norwich, John Julius. A History of Venice. New York: Vintage Books, 1989. ISBN 0-679-72197-5.

- Oman, Charles. A History of the Art of War in the Sixteenth Century. London: Methuen & Co., 1937.

- Phillips, Charles and Alan Axelrod. Encyclopedia of Wars. 3 vols. New York: Facts on File, 2005. ISBN 0-8160-2851-6.

- Taylor, Frederick Lewis. The Art of War in Italy, 1494–1529. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1973. ISBN 0-8371-5025-6.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Italian Wars. |

- Le Gall, Jean-Marie, Les guerres d'Italie (1494-1559): une lecture religieuse. Geneva: Droz, 2017.

- Boot, Max. War Made New: Technology, Warfare, and the Course of History: 1500 to Today. New York: Gotham Books, 2006. ISBN 1-59240-222-4.

- Du Bellay, Martin, Sieur de Langey. Mémoires de Martin et Guillaume du Bellay. Edited by V. L. Bourrilly and F. Vindry. 4 volumes. Paris: Société de l'histoire de France, 1908–19.

- Giovio, Paolo. Pauli Iovii Opera. Volume 3, part 1, Historiarum sui temporis. Edited by D. Visconti. Rome: Libreria dello Stato, 1957.

- Lot, Ferdinand. Recherches sur les effectifs des armées françaises des guerres d'Italie aux guerres de religion, 1494–1562. Paris: École Pratique des Hautes Études, 1962.

- Monluc, Blaise de. Commentaires. Edited by P. Courteault. 3 volumes. Paris: 1911–25. Translated by Charles Cotton as The Commentaries of Messire Blaize de Montluc (London: A. Clark, 1674).

- Monluc, Blaise de. Military Memoirs: Blaise de Monluc, The Habsburg-Valois Wars, and the French Wars of Religion. Edited by Ian Roy. London: Longmans, 1971.

- Saulx, Gaspard de, Seigneur de Tavanes. Mémoires de très noble et très illustre Gaspard de Saulx, seigneur de Tavanes, Mareschal de France, admiral des mers de Levant, Gouverneur de Provence, conseiller du Roy, et capitaine de cent hommes d'armes. Château de Lugny: Fourny, 1653.