Bowron Lake Provincial Park

Bowron Lake Provincial Park is a provincial park located in northern British Columbia, Canada, about 117 km (73 mi) east of the city of Quesnel. Other nearby towns include Wells and the historic destination of Barkerville. The park is known for its rugged glaciated mountains, cold deep lakes, waterfalls, and abundant wildlife.

| Bowron Lake Provincial Park | |

|---|---|

IUCN category II (national park) | |

.jpg) Isaac River, Bowron Lake Provincial Park | |

| |

| Nearest city | Quesnel |

| Coordinates | 53°10′N 121°05′W |

| Area | 368,700 acres (1,492 km2) |

| Established | 1961 |

| Visitors | 5,000 (in 2006) |

| Governing body | BC Parks |

| Website | Bowron Lake Provincial Park |

The main attraction is the 116 km (72 mi) canoe circuit through the Cariboo Mountains, which follows lakes, rivers, and short portages between waterways. This trip takes about a week to complete and has been described by Outside magazine as one of the top 10 canoe trips in the world.[1] An alternative to this trip is the shorter Westside route, which traverses Bowron, Swan, Spectacle, Skoi, Babcock, Unna and Rum lakes. This circuit takes two to four days. The park is open to a limited number of canoes and kayaks from May 15 to September 30.

History

Indigenous use

Many Aboriginal Canadians frequented the area that is now Bowron Lake Provincial Park before European settlement. Early settlers reported encounters with natives, who were seen hunting, trapping, fishing, and gathering in the area. Accounts of what specific groups these natives belonged to vary: some settlers speculated these were the Carrier people, while others suggested they were Shuswap or Iroquois. A 100-person village existed on Bear Lake (later known as Bowron Lake), but the village site sloughed into the lake in 1964, due to naturally occurring mudslides or possibly from seismic shock resulting from the 1964 Anchorage earthquake.[2] By that time, however, the village was uninhabited. It is likely that its prior inhabitants had been wiped out by disease, as the First Nations of the area were deeply impacted by the smallpox epidemics of the 1860s. The loss of the site prevented any form of carbon-dating to determine its true age.[3]

While very little formal archaeological work has been done, a large number of indigenous artifacts have been seen in the park, including clam middens, old campfires, arrowheads, and cache pits.[2]

As a lingering reminder of the First Nation presence in the area, today many of the landmarks and features in and around the park have indigenous names, particularly in the Carrier language. Some examples are Mount Ishpa (Carrier for "my father"), Kaza ("arrow") Mountain, the Itzul ("forest") Range, the Tediko ("girls") Range, and Lanezi ("long") Lake.[2]

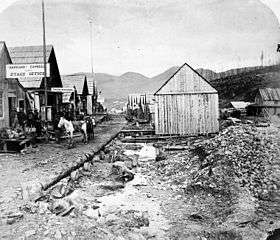

Gold rush era

The first major arrival of European settlers in the area around Bowron Lake Park came with the Cariboo gold rush in the 1860s, which was centred in the nearby town of Barkerville. While little gold mining happened within the modern boundaries of the park, miners and prospectors were the first Europeans to regularly visit Bowron Lake (then called Bear Lake) and the surrounding area.[2]

The Bowron and Cariboo mountains were continuously explored through the mid- to late 1800s. While the Canadian Pacific Railway searched for links through the mountain passes, John Bowron, the Gold Commissioner, sent exploration parties into the hills to establish mining routes into gold-bearing ground. One of these routes followed the Goat River pass, connecting Cariboo to the Tête Jaune Cache (in the Robson Valley), and was well-established enough to allow for dog sleds in the winter. This trail was eventually made obsolete when the Grand Trunk Railroad was finalized in 1914.

On 31 March 1917, Bowron Lake was adopted as the official name of the lake previously known as Bear Lake, to honour John Bowron – though some maps had started using this name as early as 1914. John Bowron himself died in 1906, and was extremely involved with the mining industry in Barkerville throughout his life.[4] The park would later inherit the name as well.[5]

Settlement and establishment as a park

While the bulk of the initial non-native population arrived with the gold rush, the area enjoyed a modest but steady influx of settlers throughout the late 19th to early 20th centuries, even as the gold rush ended. Land grants were given to soldiers returning from the First World War, and many families arrived to start farms.[2]

With the end of the gold rush, trapping and hunting came to the forefront of the region's economy. While fish and game had fed miners for years, at the turn of the century the focus shifted from hunting for sustenance to sport hunting. Wilderness guides arrived in the area and attracted an ever-increasing influx of big game hunters looking to take advantage of what was called a "hunter's paradise" in the quadrangle of lakes that now make up the park. The most prominent of these guides, Frank Kibbee, began to set up trap lines in the area in 1900[6] and built a home on the shores of Bowron Lake in 1907.[7] He was the longest-operating and most renowned guide in the region, and one of the lakes in the chain – Kibbee Lake – is today named after him.

In the 1920s, as concerns were raised about stress on the wildlife population in the Cariboo mountains, the idea was proposed to turn the area within the Bowron lake quadrangle into a game reserve, citing the success of Yellowstone in the United States. The proposed reserve would be a no-hunting sanctuary where animals could breed without human interference, allowing the population to stabilize. This was widely supported by naturalists such as Thomas and Elinor McCabe (who had arrived in 1922 and built a home on Indianpoint Lake) and Allan Brooks, as well as wilderness guides like Kibbee and Joe Wendle. Despite some initial resistance from residents of Barkerville, the case was made that establishment of the reserve would have lasting economic benefits, through the management of game to sustain the hunting industry. The Bowron Lakes Game Reserve was established by the provincial government in 1925 and Kibbee was named the reserve's first game warden shortly afterwards.[6] The reserve was originally 620 km2 (240 sq mi) in size, although many additions were made for the reserve (and later park).[2]

In the 1950s and 1960s, the cultural focus of British Columbia's protected areas shifted from game management to conservation. As a result, in 1961 the Bowron Lakes Game Reserve was declared Bowron Lake Provincial park, and the park received its largest land increases with the addition of the Betty Wendle and Wolverine drainage systems and parts of the upper Cariboo River.[2] The enthusiasm for the Bowron Region to be purely a wilderness area was so strong that most signs of human habitation were destroyed shortly after the provincial park was declared, including rail portages, trappers' cabins, and many other signs of human development. Even the home of Thomas and Elinor McCabe at Indianpoint lake was burned down, in what was described by author and guide Richard Thomas Wright as "a moment of pyromaniac enthusiasm to return the land to wilderness".[6]

Geography and geology

.jpg)

Bowron Lake Provincial park is located in the Cariboo Mountains, in central British Columbia. It is roughly 120 km (75 mi) east of the city of Quesnel, and just under 30 km (18 mi) east of the town of Wells. The park is composed of 149,207 hectares (368,699 acres) of protected wilderness, featuring many lakes and rivers nestled in mountains.[8][9] This protected area is further expanded to the south, as the park shares a border with Cariboo Mountains Provincial Park, which itself shares a border with Wells Gray Provincial Park. Together, the three parks protect over 1,007,000 hectares (2,490,000 acres) of wilderness.[10][11]

Bowron Lake Park contains three main groups of rock. The oldest is known as the Kaza Group, which is made up of mud and sand deposits that formed during the Precambrian period 600 million years ago, in a sea at the continental margin of what is now the Canadian Shield. The second group of rock, known today as the Cariboo Group, was formed 440 to 600 million years ago in the Cambrian period, when materials from the continental land mass were eroded by changing conditions in the sea. The third and youngest group, formed about 250 million years ago, is made up of sedimentary of volcanic rocks, parts of which today are exposed in various parts of the park. This third group is known as the Slide Mountain Group.[12]

Most of the visible geological features of the park were formed during mountain-building processes that started about 100 million years after the sedimentary and volcanic material was deposited. This process formed the Quesnel highlands, to the northwest of the park, and the more rugged Cariboo Mountains, to the southeast of the park.[9] Both mountain groups were largely shaped in the Cretaceous period, alongside most of British Columbia's modern drainage channels. This continued into the Eocene, until roughly 25,000 years ago when the area was covered in a 2,000-metre ice sheet. The sheet was largely static at its center over the Cariboo Mountains, resulting in the sharp features and rugged peaks that characterize the Cariboo Range. The ice covering the Quesnel Highlands, however, was much more mobile, grinding the rock down and forming broad and rounded mountains with summits between 1,600 and 2,100 metres (5,200 and 6,900 ft) – more subdued than the summits of the Cariboo Mountains, most of which are over 2,100 meters.[13]

12,000 years ago, the glaciers in the area retreated, forming the park as it exists today. Glacial till remains visible in many areas of the park, and some small glaciers still exists in its higher slopes. The retreat of the glaciers formed the park's main sequence of lakes in a roughly quadrangular shape.[14] Some examples include Indianpoint lake, formed when water from the Cariboo river was diverted by a blockage into the Indianpoint Valley, Unna Lake, which was formed from a melting kettle, and Sandy Lake and Spectacle lake, which were formed partially by meltwater streams.[13]

Ecology

Flora

The park spans sub-alpine and alpine ecosystems, and therefore contains the characteristic plants of those zones. The predominant trees are spruce and balsam, with fir (both subalpine and Douglas), cedar, and hemlock also present in various areas. For the most part, the park consists of old-growth forests, with the exception of a few areas that were burned by wildfire in the recent past.[15]

Below the tree canopy, the park is home to numerous shrubs and berry-bearing plants, which include but are not limited to twinberry, false box, bearberry, Labrador tea, cranberry, huckleberry, mountain ash, red-osier dogwood, soopolallie, white rhododendron, and sticky currant, among others. The park is also host to a very wide array of flowers.[16]

Fauna

.jpg)

Having started as a game reserve, the park is frequented by a diverse selection of animals. Moose are very common in the aquatic environments around the lakes, and mule deer are often seen in the area around Unna Lake in particular. Other large mammals such as mountain goats and caribou inhabit the park's alpine regions. The park's population of smaller mammals include semiaquatic mammals like beaver, muskrat, and river otter, as well as members of the weasel family including mink, fisher, marten, stoat, least weasel, and long-tailed weasel. Small land-dwelling mammals in the park include various voles and mice, foxes, hares, coyotes, porcupines, skunks, and squirrels.

Bears are quite common in the park – black bears are numerous in the lower altitudes around the lake, and grizzly bears frequent the alpine areas. In addition to its bears, Bowron Lake Park is home to predators like cougars, wolves, wolverines, and lynx.[17][18]

Due to its size, the park covers several habitats and therefore contains an immense variety of birds. Notable examples include Canada jays and ravens, which have adapted to human presence and often approach campsites in search of food, and waterfowl such as the loon, whose calls are commonly heard throughout the park. Swans winter on Sandy Lake, and both Canada geese and snow geese stop in the park during their migrations. Various predatory birds, such as osprey, can often be seen fishing on the lake's waters.

Many species of fish swim in the lakes themselves. Rainbow trout, dolly varden, kokanee, and rocky mountain whitefish inhabit most of the lakes year-round. Sockeye and chinook migrate through the Bowron Lake and River during their spawning runs. Sockeye typically arrive to spawn in the upper Bowron River around August, peaking during the start of September, while chinook actually spawn outside the park's grounds, in the lower Bowron River.[19]

Conservation

Fire

As in many BC parks, forest fires in Bowron Lake Park are treated as a natural process of forest rejuvenation. As such, natural fires that start in the park are generally allowed to burn, provided that they do not pose a risk to the safety of the park's users and facilities. The climate of the park can vary significantly throughout its various biogeoclimatic zones, and some areas can be significantly warmer and drier than others (for example, the Northwest portions of the park). Since they are more difficult to control, fires that start in those areas are typically not allowed to burn.[15]

Beetle infestations

The central plateau of British Columbia, where Bowron Lake Park resides, has historically been victim to infestations of mountain pine beetle,[20] which can kill large areas of tree forest if not controlled. Steps are being taken to control the spread of the beetle in Bowron Lake Park, using strategies such as the burning of affected trees, using trap trees (which are later felled and burned) to attract beetles, pheromone baiting (attractant pheromones for trap trees, or anti-aggregation pheromones for healthy trees), and biocontrol sprays. These control strategies are only used in zones of the park where beetle impact is expected to be severe; otherwise, the natural processes involving the beetles are allowed to continue unimpeded.[15]

Wildlife and fisheries

Bowron Lake Park, in conjunction with Wells Gray, Cariboo Mountain, and Cariboo River parks, form a large contiguous protected area, which acts as a haven for a wide variety of animals and wildlife. This is particularly beneficial for creatures that require large areas of undisturbed habitat, such as the grizzly bear.

The park's undeveloped wilderness provides a habitat and food source for animals such as mountain caribou, which feed off arboreal lichens that grow in the park's old growth forests. While Caribou are migratory animals, there are a number of herds that pass through the park regularly. The park is also home to an estimated three packs of wolves, who tend to feed off the park's numerous and stable population of moose. Populations of these and several other species are monitored to ensure stable populations and to maintain a healthy biodiversity in the park.

The high number of watersheds in the park make it a suitable environment for fish, and many species are widely distributed throughout its waterways. The park acts as a spawning ground for several species of trout, salmon, and others. Special regulations and limitations are applied to fishing within the park to maintain a healthy population of fish. [15]

Lakes and rivers

- Kibbee Lake

- Indianpoint Lake

- Isaac Lake

- Lanezi Lake

- Sandy Lake

- Spectacle Lake

- Babcock Lake

- Swan Lake

- Bowron Lake

- Unna Lake

- Cariboo River

- Bowron River

Gallery

Cariboo Mountains from Isaac Lake

Cariboo Mountains from Isaac Lake Ishpa Mountain side from Lanezi Lake

Ishpa Mountain side from Lanezi Lake.jpg) Indianpoint Lake

Indianpoint Lake.jpg) Isaac Lake before a storm

Isaac Lake before a storm.jpg) Sandy Lake during civil twilight

Sandy Lake during civil twilight

References

- "25 of the Very Best Outdoor Adventures in British Columbia". Archived from the original on 2019-10-11. Retrieved 2019-10-11.

- Environment, Ministry of. "Ministry of Environment - Bowron Lake". www.env.gov.bc.ca. Archived from the original on 2019-06-07. Retrieved 2019-06-07.

- "Bowron Lakes History". sea to sky wilderness adventures. Archived from the original on 2019-06-07. Retrieved 2019-06-07.

- "BC Geographical Names". apps.gov.bc.ca. Archived from the original on 2019-06-07. Retrieved 2019-06-07.

- Wright (1985) pp. 35-36

- Jorgenson, Mica (Autumn 2012). ""A Business Proposition": Naturalists, Guides, and Sportsmen in the Formation of the Bowron Lakes Game Reserve". BC Studies: The British Columbian Quarterly. 175: 9–34. Archived from the original on 2018-04-15. Retrieved 2019-06-12.

- Wright (1985) p. 39

- "Bowron Lake Provincial Park" (PDF). eng.gov.bc.ca. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-06-13. Retrieved 2019-06-13.

- "Bowron Lake Park". www.spacesfornature.org. Archived from the original on 2014-12-21. Retrieved 2019-06-13.

- Environment, Ministry of. "Cariboo Mountains Provincial Park - BC Parks". www.env.gov.bc.ca. Archived from the original on 2019-06-07. Retrieved 2019-06-13.

- Environment, Ministry of. "Wells Gray Provincial Park - BC Parks". www.env.gov.bc.ca. Archived from the original on 2011-12-31. Retrieved 2019-06-13.

- Wright, Richard Thomas (1985). The Bowron Lakes: A Year-Round Guide. Vancouver, British Columbia: Maclean-Hunter Ltd. p. 23. ISBN 0-88896-148-0.

- Wright, Richard Thomas (1985). The Bowron Lakes: A Year-Round Guide. Vancouver, BC: Maclean-Hunter Ltd. pp. 24–26. ISBN 0-88896-148-0.

- "Forest Health and Fire Management Zones - Bowron, Cariboo River and Cariboo Mountains Parks Management Plan" (PDF). eng.gov.bc.ca. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-06-14. Retrieved 2019-06-14.

- "Natural, Cultural Heritage and Recreation Values Management" (PDF). eng.gov.bc.ca. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-07-26. Retrieved 2019-07-26.

- Wright, Richard Thomas (1994). Bowron Lake Provincial Park: The All-Seasons Guide. Canada: Heritage House Publishing. p. 49. ISBN 1-895811-04-X.

- Wright, Richard Thomas (1994). Bowron Lake Provincial Park: The All-Seasons Guide. Canada: Heritage House Publishing Company. pp. 50–54. ISBN 1-895811-04-X.

- Wright, Richard Thomas (1994). Bowron Lake Provincial Park: The All-Seasons Guide. Canada: Heritage House Publishing Company. p. 124. ISBN 1-895811-04-X.

- Wright, Richard Thomas (1994). Bowron Lake Provincial Park: The All-Seasons Guide. Canada: Heritage House Publishing Company. pp. 54–55. ISBN 1-895811-04-X.

- "History of Mountain Pine Beetle Infestation in B.C." (PDF). eng.gov.bc.ca. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-07-26. Retrieved 2019-07-26.

- Harris, 1991. British Columbia's Wilderness Canoe Circuit. Gordon Soules Book Publishers

- Wright, 1997. Bowron Lake Provincial Park: Canoe Country British Columbia, Heritage House Pub Co Ltd. 128p

- Wright, Richard Thomas (1985). The Bowron Lakes, a year-round guide. Maclean Hunter, Vancouver. ISBN 0-88896-148-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bowron Lake Provincial Park. |