Benin City

Benin City is the capital and largest city of Edo State in southern Nigeria.[1] It is situated approximately 40 kilometres (25 mi) north of the Benin River and 320 kilometres (200 mi) by road east of Lagos. Benin City is the centre of Nigeria's rubber industry, and oil production is also a significant industry.[2]

Benin City | |

|---|---|

City | |

| Benin | |

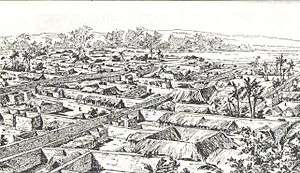

Aerial view of Benin City | |

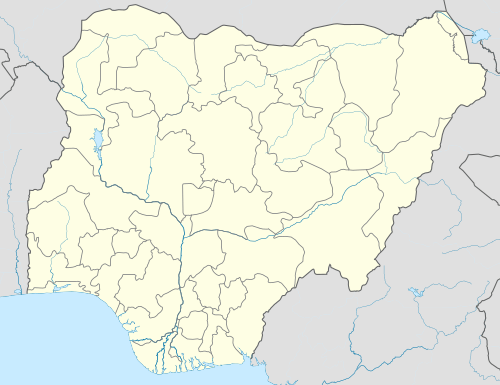

Benin City Location in Nigeria | |

| Coordinates: 6°20′00″N 5°37′20″E | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,204 km2 (465 sq mi) |

| Population (2015) | |

| • Total | 1,495,800 |

| • Rank | 4th |

| • Density | 1,200/km2 (3,200/sq mi) |

| Climate | Aw |

Benin City was the principal city of the Edo kingdom of Benin, which flourished during the 13th to the 19th century. It was destroyed in 1897 by the British after the Edo assaulted an earlier British expedition, which had been told not to enter the city during a religious festival but nonetheless attempted to do so. Before burning the city down, the British pillaged it, taking many of its famous bronzes, ivory, and other treasures.[3]

Although traces of the old wall and moat remain, the new city is a close-packed pattern of houses and streets converging on the palace and compound of the oba (sacred king) and the government offices. In the main square sits a statue of Emotan, a woman honoured for assisting a 15th-century prince attempting to regain power and who later became Oba Ewuare. The present oba retains traditional and advisory roles in government.[4]

The indigenous people of Benin City are the Edo people (The Benin People), and they speak the Edo language and other Edoid languages. The people of the city have one of the richest dress cultures on the African continent and are known for their beads, body marks, bangles, anklets, and raffia work.[5]

History

Edo people

The original people and founders of the Ẹdo Empire and the Ẹdo people initially were ruled by the Ogiso (Kings of the Sky) dynasty who called their land Igodomigodo. Igodo, the first Ogiso, wielded much influence and gained popularity as a good ruler. He died after a long reign and was succeeded by Ere, his eldest son. In the 12th century, great palace intrigue and the battle for power erupted between the warrior crown prince Ekaladerhan, son of the last Ogiso and his young paternal uncle. In anger over an oracle, Prince Ekaladerhan left the royal court with his warriors. When his old father the Ogiso died, the Ogiso dynasty was ended as the people and royal kingmakers preferred their king's son as natural next in line to rule.

The exiled Ekaladerhan, who was not known, gained the title of Oni Ile-fe Izoduwa, which has been corrected in the Yoruba language to Ọọni (Ọghẹnẹ) of Ile-Ifẹ Oduduwa. He refused to return to Ẹdo but sent his son Ọranmiyan to become king in his place.[6] Prince Ọranmiyan took up residence in the palace built for him at Uzama by the elders, now a coronation shrine. Soon after he married a beautiful lady, Ẹrinmwide, daughter of Osa-nego, the ninth Enogie of Edọ. He and Erinwide had a son. After some years he called a meeting of the people and renounced his office, remarking that the country was a land of vexation, Ile-Ibinu, and that only a child born, trained and educated in the arts and mysteries of the land could reign over the people. The country was afterward known by this name. He caused his son born to him by Ẹrinmwide to be made King in his place and returned to Yoruba land Ile-Ife. After some years in Ife, he left for Ọyọ, where he also left a son behind upon leaving, and his son Ajaka ultimately became the first Alaafin of Ọyọ of the present line, while Ọranmiyan (the exiled Prince Ekaladerhan, also known as Izoduwa) himself was reigning as Ọọni of Ifẹ. Therefore, Ọranmiyan of Ife, the father of Ẹwẹka I, the Ọba of Benin, was also the father of Ajaka, the first Alaafin of Ọyọ.[7] Ọọni of Ifẹ. Allegedly Ọba Ẹwẹka later changed the name of the city of Ile-Binu, the capital of the Benin kingdom, to "Ubinu." This name would be reinterpreted by the Portuguese as "Benin" in their own language. Around 1470, Ẹwuare changed the name of the state to Ẹdo.[8] This was about the time the people of Ọkpẹkpẹ migrated from Benin City. Alternatively, Yorubas believe Oduduwa was from the Middle East and migrated from that area to the present Ile Ife. Because of his power and military might, he was able to conquer the enemies invading Ife city. That was why the people of Ile Ife made him the King or Oni of Ife city. In any case, it is agreed upon by both the Yoruba and Edos that Oduduwa sent his son Prince Oramiyan of Ife to rule Benin City and found the Oba dynasty in Benin City.

European Contact

The Portuguese visited Benin City around 1485. Benin grew rich during the 16th and 17th centuries due to trade within southern Nigeria, as well as through trade with Europeans, mostly in pepper and ivory. In the early 16th century, the Ọba sent an ambassador to Lisbon, and the King of Portugal sent Christian missionaries to Benin. Some residents of Benin could still speak a pidgin Portuguese in the late 19th century. Many Portuguese loan words can still be found today in the languages of the area. A Portuguese captain described the city in 1691:"Great Benin, where the king resides, is larger than Lisbon; all the streets run straight and as far as the eye can see. The houses are large, especially that of the king, which is richly decorated and has fine columns. The city is wealthy and industrious. It is so well governed that theft is unknown and the people live in such security that they have no doors to their houses". This was at a time when theft and murder were rife in London.[9][10]

On 17 February 1897, Benin City fell to the British.[5] In the "Punitive Expedition", a 1,200-strong British force, under the command of Admiral Sir Harry Rawson, conquered and razed the city after all but two men from a previous British expeditionary force led by Acting Consul General Philips were killed.[11][12] Alan Boisragon, one of the survivors of the Benin Massacre, includes references to the practice of human sacrifice in the city in a firsthand account written in 1898 (one year after the Punitive Expedition).[13] James D. Graham notes that although "there is little doubt that human sacrifices were an integral part of the Benin state religion from very early days," firsthand accounts regarding such acts often varied significantly, with some reporting them and others making no mention of them.[14]

The "Benin Bronzes", portrait figures, busts and groups created in iron, carved ivory, and especially in brass (conventionally called "bronze"), were taken from the city by the British and are currently displayed in various museums around the world.[5] Some of the bronzes were auctioned off to compensate for the expenses incurred during the invasion of the city. Most of these artifacts can be found today in British museums and other parts of the world. In recent years, various appeals have gone to the British government to return such artifacts. The most prominent of these artifacts was the famous Queen Idia mask used as a mascot during the Second Festival of Arts Culture (FESTAC '77) held in Nigeria in 1977 now known as "Festac Mask".

The capture of Benin paved the way for British military occupation and the merging of later regional British conquests into the Niger Coast Protectorate, the Protectorate of Southern Nigeria and finally, into the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria. The British permitted the restoration of the Benin monarchy in 1914, but true political power still lay with the colonial administration of Nigeria.

Nigerian Independence

Following Nigeria's independence from British rule in 1960, Benin City became the capital of Mid-Western Region when the region was split from Western Region in June 1963; it remained the capital of the region when the region was renamed Bendel State in 1976, and became the state capital of Ẹdo State when Bendel was split into Delta and Edo states in 1991.[15]

The Benin imperialism started in the last decade of the thirteen century by Oba Ewedo.[16]

Geography

Climate

| Climate data for Benin City | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 34.4 (93.9) |

36.1 (97.0) |

36.1 (97.0) |

35.6 (96.1) |

35.0 (95.0) |

33.3 (91.9) |

31.7 (89.1) |

31.1 (88.0) |

32.8 (91.0) |

32.8 (91.0) |

34.4 (93.9) |

34.4 (93.9) |

36.1 (97.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 31.9 (89.4) |

33.3 (91.9) |

33.0 (91.4) |

32.4 (90.3) |

31.6 (88.9) |

29.9 (85.8) |

27.9 (82.2) |

27.9 (82.2) |

28.8 (83.8) |

30.3 (86.5) |

31.8 (89.2) |

32.0 (89.6) |

30.9 (87.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 25.8 (78.4) |

26.7 (80.1) |

26.7 (80.1) |

26.4 (79.5) |

25.9 (78.6) |

24.9 (76.8) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.7 (74.7) |

24.3 (75.7) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.9 (78.6) |

25.7 (78.3) |

25.4 (77.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 21.4 (70.5) |

22.1 (71.8) |

22.6 (72.7) |

22.6 (72.7) |

22.6 (72.7) |

21.9 (71.4) |

21.6 (70.9) |

21.2 (70.2) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.8 (71.2) |

22.1 (71.8) |

21.2 (70.2) |

21.9 (71.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 12.8 (55.0) |

13.3 (55.9) |

18.3 (64.9) |

19.4 (66.9) |

19.4 (66.9) |

18.3 (64.9) |

16.7 (62.1) |

16.1 (61.0) |

18.9 (66.0) |

18.9 (66.0) |

15.6 (60.1) |

14.4 (57.9) |

12.8 (55.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 18 (0.7) |

33 (1.3) |

97 (3.8) |

168 (6.6) |

213 (8.4) |

302 (11.9) |

320 (12.6) |

211 (8.3) |

318 (12.5) |

241 (9.5) |

76 (3.0) |

15 (0.6) |

2,012 (79.2) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.3 mm) | 2 | 4 | 9 | 12 | 16 | 20 | 23 | 19 | 25 | 21 | 7 | 2 | 160 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 84 | 81 | 84 | 85 | 87 | 90 | 93 | 92 | 91 | 89 | 86 | 84 | 87 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 179.8 | 178.0 | 173.6 | 177.0 | 176.7 | 144.0 | 99.2 | 89.9 | 81.0 | 148.8 | 192.0 | 213.9 | 1,853.9 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 5.8 | 6.3 | 5.6 | 5.9 | 5.7 | 4.8 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 2.7 | 4.8 | 6.4 | 6.9 | 5.1 |

| Source: Deutscher Wetterdienst[17] | |||||||||||||

Education

Benin City is home to some of Nigeria's institutions of higher learning, namely, the University of Benin located at Ugbowo and Ekenwan, the Ambrose Alli University located at Ekpoma, the College of Education Ekiadolor, Igbinedion University, the Benson Idahosa University and Wellspring University. Secondary schools in Nigeria are, among others, Edo College, Edo Boys High School (Adolo College), Western Boys High School, Oba Ewuare Grammar School, Greater Tomorrow Secondary School, Garrick Memorial Secondary School, Winrose Secondary School, Asoro Grammar School, Eghosa Grammar School, Edokpolor Grammar School, Niger College, Presentation National High School, Immaculate Conception College, Idia College, University of Benin Demonstration Secondary School, University Preparatory Secondary School, Auntie Maria School, Benin Technical College, Headquarters of Word of Faith Group of Schools, Lydia Group of Schools, Nosakhare Model Education Centre and Igbinedion Educational Center, Federal Government Girls College, Benin City, Paragon Comprehensive College, and Itohan Girls Grammar School. Some of the vocational schools in Benin City include Micro International Training Center, Computer Technology and Training Center, Okunbor Group of Schools.

Culture

Attractions in the city include the National Museum, the Oba Palace, Igun Street (Famous for bronze casting and other metal works). Other attractions include various festivals and the Benin Moats (measuring about 20 to 40 ft), the King's Square (known as Ring Road)[18] and its traditional markets.

The Binis are known for bronze sculpture, its casting skills, and their arts and craft. Benin City is also the home of one of the oldest sustained monarchies in the world. Various festivals are held in Benin City yearly to celebrate various historic occasions and seasons. Igue festival is the most popular of the festivals where the Oba celebrates the history and culture of his people and blesses the land and the people. It is celebrated at a time between Christmas and New Year.[19]

Bini market days

The "Bini" people have four market days: Ekioba, Ekenaka, Agbado, and Eken.

Transportation

Benin Airport serves the city with four commercial airlines flying to it, including Arik Air.

Notable people

- General Godwin Abbe, Former Nigerian Minister for Interior and Defence

- Professor Ambrose Folorunsho Alli, Former governor of the defunct Bendel State. He created the Bendel State University now named after him.

- Chief Anthony Anenih, Chairman, the board of trustees (PDP) and Nigeria's former Minister of Works

- Archbishop John Edokpolo, Honourable Minister of Trade and Founder of Edokpolor Grammar School

- Chief Francis Edo-Osagie, businessman

- Chief Jacob U. Egharevba, a Bini historian and traditional chief

- Chief Anthony Enahoro, anti-colonial and pro-democracy activist and politician

- Bright Enobakhare, football player

- Eghosa Asemota Agbonifo, Politician, coordinator of Michael Agbonifo shoe a child foundation

- Festus Ezeli, basketball player

- Dr Abel Guobadia, former Chairman of Nigeria's Independent National Electoral Commission

- Archbishop Benson Idahosa, Founder of Church of God Mission International Incorporated and Idahosa World Outreach (IWO)

- Felix Idubor, artist

- Suyi Davies Okungbowa, African fantasy and speculative fiction author

- Chief Gabriel Igbinedion, business mogul and Esama of Benin kingdom

- Professor Festus Iyayi, novelist and first African to win the Commonwealth Writers Prize

- Suleman Johnson, senior pastor and general overseer of Omega Fire Ministries International

- Felix Liberty, musician

- Samuel Ogbemudia, former governor of the Midwest region of Nigeria and later Bendel state

- Sonny Okosun, musician

- Professor Osasere Orumwense, Vice-Chancellor of University of Benin

- Debrah Eunice Osagiede Founder of Spirit and Life Bible Church

- Professor Osayuki Godwin Oshodin, former Vice-Chancellor of University of Benin

- Demi Isaac Oviawe, Ireland-based actress

- Pastor Chris Oyakhilome, founder and president of Believers LoveWorld Incorporated, also known as Christ Embassy

- Modupe Ozolua , Body Enhancement and Reconstructive Surgeon

- Sir Victor Uwaifo, musician

References

- "Benin City | History & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- "International Rubber Study Group - Nigeria". www.rubberstudy.com. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- "Benin City | History & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- "Oba | sacred king". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Benin, City, Nigeria, Archived 25 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2005 Columbia University Press. Retrieved 18 February 2007

- "The kingdom of Benin". BBC Bitesize. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- "Benin City | Hometown.ng™". Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- The Sun, Wednesday, 17 September 2008.

- Koutonin, Mawuna (18 March 2016). "Story of cities #5: Benin City, the mighty medieval capital now lost without trace". Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Elias, Taslim Olawale (1988). Africa and the development of international law (Second edition, first published 1972 ed.). Springer Netherlands. p. 12. ISBN 9789024737963. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- Taub, Ben (10 April 2017). "The Desperate Journey of a Trafficked Girl". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 3 April 2017.

In 1897, after the Edo slaughtered a British delegation, colonial forces, pledging to end slavery and ritual sacrifice, ransacked the city and burned it to the ground.

- Obinyan, Thomas Uwadiale (1988). "The Annexation of Benin". Journal of Black Studies. 19 (1): 29–40. doi:10.1177/002193478801900103. JSTOR 2784423.

- Boisragon, A. The Benin Massacre(1897).

- Graham, James D. (1965). "The Slave Trade, Depopulation and Human Sacrifice in Benin History: The General Approach". Cahiers d'Études Africaines. 5 (18): 317–334. doi:10.3406/cea.1965.3035. JSTOR 4390897.

- "Bendel | state, Nigeria". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Toyin, Falola (2005). Akinwunmi, Ogundiran (ed.). Precolonial Nigeria (2005 ed.). African World Press Inc. pp. 264–265. ISBN 978-1592212194.

- "Klimatafel von Benin City / Nigeria" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961-1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- Trillo, Richard (2008), The Rough Guide to West Africa, Rough Guides, p. 2629, ISBN 978-1-84353-850-9

- www.edo-nation.net https://www.edo-nation.net/igue.htm. Retrieved 31 May 2020. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

Bibliography

- Bondarenko D. M. A Homoarchic Alternative to the Homoarchic State: Benin Kingdom of the Thirteenth - Nineteenth Centuries. Social Evolution & History. 2005. vol. 4, no 2. pp. 18–88.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Benin City. |