Kano

Kano is the capital city of Kano State in North West, Nigeria. It is situated in the Sahelian geographic region, south of the Sahara. Kano is the commercial nerve centre of Northern Nigeria and is the second largest city in Nigeria. The Kano metropolis initially covered 137 square kilometres (53 square miles), and comprised forty four local government areas (LGAs)—Kano Municipal, Fagge, Dala, Gwale, Tarauni and Nasarawa; However, it now covers two additional LGAs—Ungogo and Kumbotso. The total area of Metropolitan Kano is now 499 square kilometres (193 square miles), with a population of 2,828,861 as of the 2006 Nigerian census; the latest official estimate (for 2016) is 3,931,300.

Kano | |

|---|---|

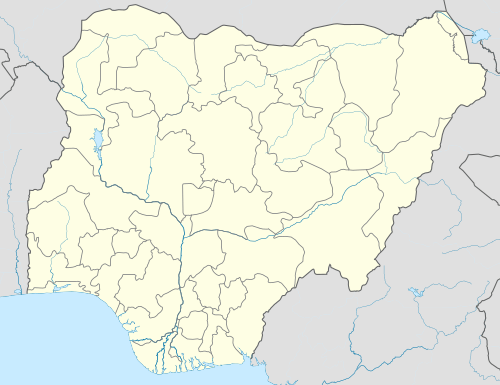

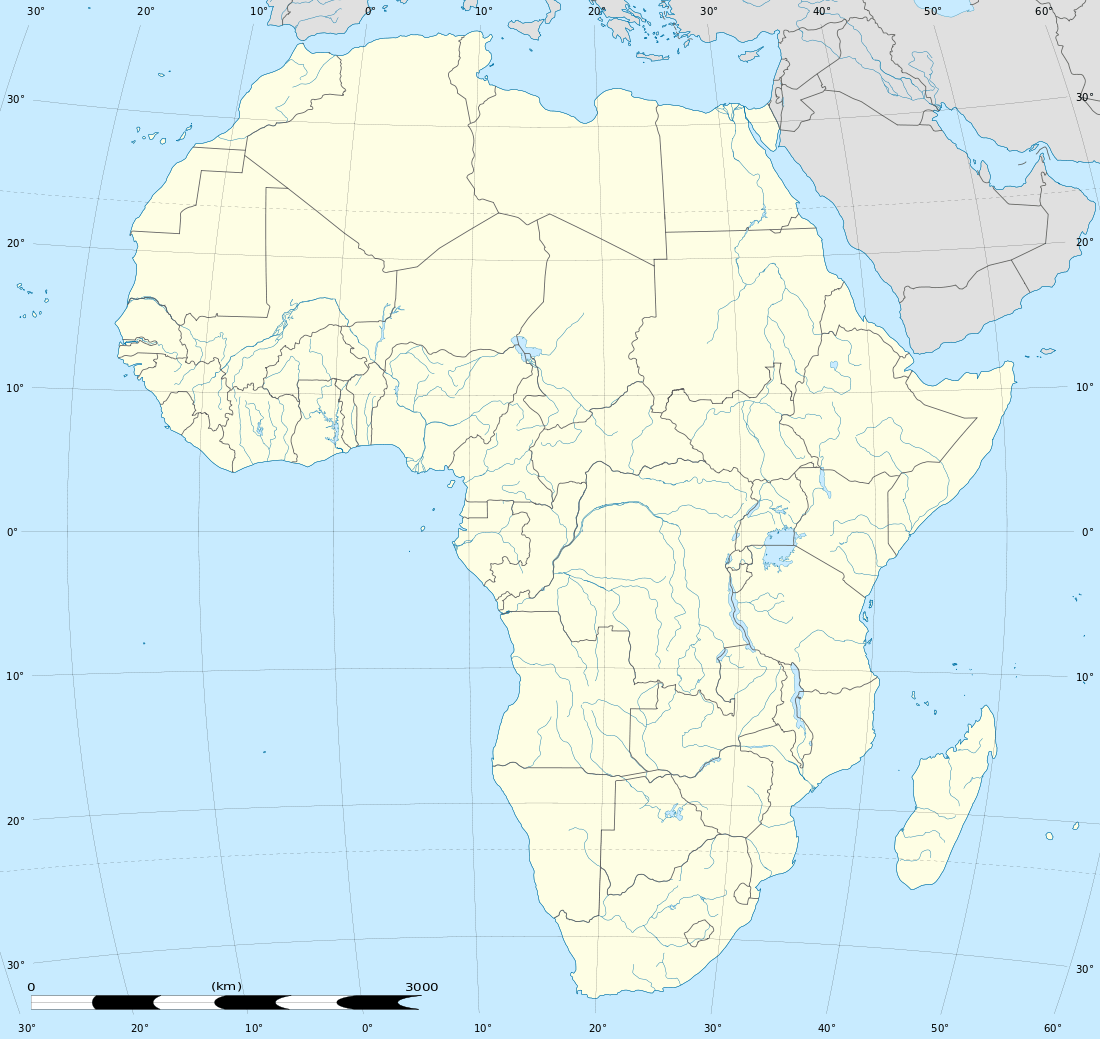

Kano Map of Nigeria showing the location of Kano  Kano Kano (Africa) | |

| Coordinates: 12°00′N 8°31′E | |

| Country | |

| State | Kano State |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Abdullahi Umar Ganduje (APC) |

| • Emir | Aminu Ado Bayero |

| • Local Government Chairman of Kano Municipal | Hon. Alh. Sabo Muhammad Dantata |

| Area | |

| • City | 499 km2 (193 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 251 km2 (97 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 488 m (1,601 ft) |

| Population (2006 census) | |

| • City | 2,828,861 |

| • Estimate (2016) | 3,931,300 |

| • Rank | 2nd |

| • Density | 5,700/km2 (15,000/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 3,550,000 |

| • Urban density | 14,100/km2 (37,000/sq mi) |

| [1] | |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (WAT) |

| Climate | Aw |

The principal inhabitants of the city are the Hausa people. However, there are few who speak Fulani language. As in most parts of northern Nigeria, the Hausa language is widely spoken in Kano. The city is the capital of the Kano Emirate. The current emir, Aminu Ado Bayero, was enthroned on 9 March 2020 after the last emir Muhammadu Sanusi II was deposed. The city's Mallam Aminu Kano International Airport, the main airport serving northern Nigeria, was named after politician Aminu Kano.[2]

History

In the 7th century, Dala Hill, a residual hill in Kano, was the site of a hunting and gathering community that engaged in iron work (nok culture); it is unknown whether these were Hausa people or speakers of Niger–Congo languages.[3] Kano was originally known as Dala, after the hill, and was referred to as such as late as the end of the 15th century and the beginning of the 16th by Bornoan sources.[4]

The Kano Chronicle identifies Barbushe, a warrior priest of Dala Hill female spirit deity known as Tsumbura, Barbushe is from the lineage of the hunter family (maparauta) who were the city's first settlers. (Elizabeth Isichei notes that the description of Barbushe is similar to those of Sao people.[5]) While small chiefdoms were previously present in the area, according to the Kano Chronicle, Bagauda son of Bawo and grandson of the mythical hero Bayajidda,[6] became the first king of Kano in 999, reigning until 1063.[7] [8][9] His grandson Gijimasu (1095–1134), the third king, began building city walls (badala/ganuwa) at the foot of Dala Hill. His own son, Tsaraki (1136–1194), the fifth king, completed them during his reign.[9]

In the 12th century Ali Yaji as King of Kano renounced his allegiance to the cult of Tsumburbura, converted to Islam and proclaimed the Sultanate that was to last until its fall in the 19th century. The reign of Yaji ensued an era of expansionism that saw Kano becoming the capital of a pseudo Habe Empire.

In 1463 Muhammad Rumfa (reigned 1463–1499) ascended the throne. During his reign, political pressure from the rising Songhai Empire forced him to take Auwa, the daughter of Askiyah the Great as his wife. She was to later become the first female Madaki of Kano. Rumfa reformed the city, expanded the Sahelian Gidan Rumfa (Emir's Palace), and played a role in the further Islamization of the city,[10] as he urged prominent residents to convert.[11] The Kano Chronicle attributes a total of twelve "innovations" to Rumfa.[12]

According to the Kano Chronicle, the thirty-seventh Sarkin Kano (King of Kano) was Mohammed Sharef (1703–1731). His successor, Kumbari dan Sharefa (1731–1743), engaged in major battles with Sokoto as a longterm rivalry.

Fulani conquest and rule

At the beginning of the 19th century, Fulani Islamic leader Usman dan Fodio led a jihad affecting much of central Sudan which demolished the Habe kingdom, leading to the emergence of the Sokoto Caliphate. In 1805 the last sultan of Kano was defeated by the Jobe Clan of the Fulani, and Kano became an Emirate of the Caliphate. Kano was already the largest and most prosperous province of the empire.[13] This was one of the last major slave societies, with high percentages of enslaved population long after the Atlantic slave trade had been cut off. Heinrich Barth called Kano the greatest emporium of central Africa; he was a German scholar who spent several years in northern Nigeria in the 1850s and estimated the percentage of slaves in Kano to be at least 50%, most of whom lived in slave villages.[13]

The city suffered famines from 1807–10, in the 1830s, 1847, 1855, 1863, 1873, 1884, and from 1889 until 1890.[14]

From 1893 until 1895, two rival claimants for the throne fought a civil war, or Basasa. With the help of royal slaves, Yusufu was victorious over his brother Tukur and claimed the title of emir.[15]

British colonization and rule

In March 1903 after a scant resistance, the Fort of Kano was captured by the British, It quickly replaced Lokoja as the administrative centre of Northern Nigeria. It was replaced as the centre of government by Zungeru and later Kaduna and only regained administrative significance with the creation of Kano State following Nigerian independence.

From 1913 to 1914, as the peanut business was expanding, Kano suffered a major drought, which caused a famine.[16] Other famines during British rule occurred in 1908, 1920, 1927, 1943, 1951, 1956, and 1958.[14]

By 1922, groundnut trader Alhassan Dantata had become the richest businessman in the Kano Emirate, surpassing fellow merchants Umaru Sharubutu Koki and Maikano Agogo.[17]

In May 1953, an inter-ethnic riot arose due to southern newspapers misreporting on the nature of a disagreement between northern and southern politicians in the House of Representatives.[18] Thousands of Nigerians of southern origin died as a result a political sparked riot.[19]

Post-independence history

Ado Bayero became emir of Kano in 1963. Kano state was created in 1967 from the then Northern Nigeria by the Federal military government. The first military police commissioner, Audu Bako, is credited with building a solid foundation for the progress of a modern society. Most of the social amenities in the state are credited to him. The first civilian governor was Abubakar Rimi.

In the late 1960s, a ground tracking station was established on the hill called Goron Dutse overlooking Kano to track NASA's Mercury and Gemini spacecraft when they passed over Africa.

In December 1980, radical preacher Mohammed Marwa Maitatsine led a riot. He was killed by security forces, but his followers later started uprisings in other northern cities.[20]

After the introduction of sharia law in Kano State in the early 2000s, many Christians left the city.[21] 100 people were killed in riots over the sharia issue during October 2001.[22][23]

In November 2007, political violence broke out in the city after the People's Democratic Party (PDP) accused the All Nigeria Peoples Party (ANPP) of rigging the November 17 local government elections.[24] (The ANPP won in 36 of the state's 44 local Government Areas.)[25] Hundreds of youths took to the streets, over 300 of whom were arrested; at least 25 people were killed. Buildings set on fire include a sharia police station, an Islamic centre, and a council secretariat. 280 federal soldiers were deployed around the city.[26]

In January 2012, a series of bomb attacks killed up to 162 people. Four police stations, the State Security Service headquarters, passport offices and immigration centres were attacked. Jihadist insurgents Boko Haram claimed responsibility.[27] After the bombings, Kano was placed under curfew.[28] The Boko Haram insurgency continued with mass murders in March 2013 and November 2014.

Geography

Kano is 481 metres (1,578 feet) above sea level. The city lies to the north of the Jos Plateau, in the Sudanian Savanna region that stretches across the south of the Sahel. The city lies near where the Kano and Challawa rivers flowing from the southwest converge to form the Hadejia River, which eventually flows into Lake Chad to the east.

Climate

Kano has a tropical savanna climate. The city has on average about 980 mm (38.6 in) of precipitation per year, the large majority of which falls from June through September. Like the vast majority of Nigeria, Kano is very hot for most of the year, peaking in April. From December through February, the city is less hot, with nighttime temperatures during the months of December, January and February having average low temperatures of 14 to 16 °C (57 to 61 °F).

| Climate data for Kano (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 29.0 (84.2) |

32.4 (90.3) |

36.4 (97.5) |

39.1 (102.4) |

37.1 (98.8) |

35.4 (95.7) |

32.0 (89.6) |

30.9 (87.6) |

32.3 (90.1) |

34.5 (94.1) |

33.1 (91.6) |

29.9 (85.8) |

33.5 (92.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 13.7 (56.7) |

16.2 (61.2) |

20.4 (68.7) |

24.5 (76.1) |

25.0 (77.0) |

23.7 (74.7) |

22.1 (71.8) |

21.2 (70.2) |

21.9 (71.4) |

21.2 (70.2) |

17.1 (62.8) |

14.2 (57.6) |

20.1 (68.2) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.01) |

1.0 (0.04) |

14.1 (0.56) |

57.3 (2.26) |

132.5 (5.22) |

281.0 (11.06) |

323.9 (12.75) |

155.8 (6.13) |

14.1 (0.56) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

980.0 (38.58) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 8 | 13 | 15 | 24 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 72 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 15:00 LST) | 17.0 | 13.2 | 13.2 | 19.1 | 29.5 | 44.5 | 58.9 | 63.6 | 55.0 | 30.1 | 18.1 | 17.4 | 31.6 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 244.9 | 232.4 | 238.7 | 234.0 | 263.5 | 261.0 | 229.4 | 220.1 | 240.0 | 266.6 | 264.0 | 260.4 | 2,955 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 7.9 | 8.3 | 7.7 | 7.8 | 8.5 | 8.7 | 7.4 | 7.1 | 8.0 | 8.6 | 8.8 | 8.4 | 8.1 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organization[29] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (sun and relative humidity, 1961–1990)[30] | |||||||||||||

Education

Notable educational institutions include:-

- Bayero University Kano - founded in 1962.

- Kano State Polytechnic - founded in 1975

Places of worship

Among the places of worship, they are predominantly Muslims mosques.[31] There are also Christian churches and temples : Church of Nigeria (Anglican Communion), Presbyterian Church of Nigeria (World Communion of Reformed Churches), Nigerian Baptist Convention (Baptist World Alliance), Living Faith Church Worldwide, Redeemed Christian Church of God, Assemblies of God, Roman Catholic Diocese of Kano (Catholic Church).

Transport

The city has an airport, the Mallam Aminu Kano International Airport.

After a hiatus of many years, the railway line from Kano to Lagos was rehabilitated by 2013. The train trip to Lagos takes 30 hours and costs the equivalent of US$12, only a quarter of the equivalent bus fare.[32]

In 2014, a new double track, standard gauge line is under construction from Lagos.[33]

From 2006 to 2015, backed by high oil prices, major highways, overhead bridges and other transportation infrastructure were built by the state government. The most notable of these are the Silver Jubilee flyover bridge at Kofar Nassarawa, the Kofar Kabuga underpass and various 6-lane highways in the city.

In 2017, a 74-km, four-line light rail network was announced by the Kano State Ministry of Works, Housing & Transport; with a US$1.8 billion contract signed with China Railway Construction Corporation.[34][35]

Economy

The economic significance of Kano dates back to the pre-colonial Africa when Kano city served as the southernmost point of the famous trans-Sahara trade routes. Kano was well connected with many cities in North Africa and some cities in southern Europe.[36] Formerly walled, most of the gates to the Old City survive. The Old City houses the vast Kurmi Market, known for its crafts, while old dye pits—still in use—lie nearby. In the Old City are the Emir's Palace, the Great Mosque, and the Gidan Makama Museum.

The products exported from Kano to North Africa include textile materials, leather and grains. Kano was connected with trans-Atlantic trade in 1911 when a railway line reached Kano. Kano is a major centre for the production and export of agricultural products like hides, skins, peanuts, and cotton. Kano houses a railway station with trains to Lagos routed through Kaduna, while Mallam Aminu Kano International Airport lies nearby. Because Kano is north of the rail junction at Kaduna, it has equal access to the seaports at Lagos and Port Harcourt. The city maintains its economy and business even in the 21st century with it producing the richest black man—Aliko Dangote—whose great grand father Alhassan Dantata was the richest during Nigeria's colonial period.

Ado Bayero became emir of Kano in 1963. Kano state was created in 1967 from the then Northern Nigeria by the Federal military government. The first military police commissioner, Audu Bako, is credited with building a solid foundation for the progress of a modern society.I was there at the time, and found him very progressive. He started a lot of development projects—network of roads, a reliable urban water supply. He was a keen farmer himself and funded construction of number of dams to provide irrigation. Thanks to his policies Kano produced all types produce and export it to the neighbouring states.

Inconsistent government policies and sporadic electricity supply have hampered industry, so that Kano's economy relies on trade, retail and services. The emergence of large retail outlets starting from early 2000 with Sahad Stores and Jifatu departmental stores revived investor confidence in the sector which led to the construction of the Ado Bayero mall in, then the largest shopping mall in Nigeria with a retail space of 24,000 square metres (260,000 square feet)[37] It has the popular filmhouse cinemas, the South African retail giants Shoprite and Game stores as anchor partners.

Kano has six districts: the Old City, Bompai, Fagge, Sabon Gari, Syrian Quarter, and Nassarawa.[38]

As of November 2007, there were plans to establish an information technology park in the city.[39]

The city is supplied with water by the nearby Challawa Gorge Dam, which is being considered as a source of hydro power.[40]

Durbar festival

The emir of Kano hosts a Durbar to mark and celebrate the two annual Muslim festivals Eid al-Fitr (to mark the end of the Holy Month of Ramadan) and Eid al-Adha (to mark the Hajj Holy Pilgrimage). The Durbar culminates in a procession of highly elaborately dressed horsemen who pass through the city to the emir's palace. Once assembled near the palace, groups of horsemen, each group representing a nearby village, take it in turns to charge toward the emir, pulling up just feet in front of the seated dignitaries to offer their respect and allegiance.

Notable people

- Muhammadu Abubakar Rimi former Governor of Kano state.

- Sani Abacha former Nigerian Head of State

- Pamela Abalu, Nigerian-American entrepreneur and design leader.

- Aliko Dangote, entrepreneur

- Alhassan Dantata, businessman

- Rabiu Kwankwaso, politician, Former Governor Of Kano State Also A Former Minister Of Defense and Water Resources Engr

- Murtala Mohammed, Former Head of States, Federal Republic of Nigeria

- Isyaku Rabiu, businessman

- Sanusi Lamido Sanusi, banker

- Ibrahim Shekarau, politician, Former Governor Of Kano State And Former Minister Of Education, currently Nigerian Senate representing Kano Central

- Alhassan Yusuf, footballer, currently plays for IFK Göteborg in Sweden

See also

References

- "Metro Kano". citypopulation.de. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- "Kano state". Nigerian Information Portal. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- Iliffe, John (2007). Africans: The Huistory of a Continent. Cambridge University Press. p. 75. ISBN 0-521-86438-0.

- Nast, Heidi J (2005). Concubines and Power: Five Hundred Years in a Northern Nigerian Palace. University of Minnesota Press. p. 60. ISBN 0-8166-4154-4.

- Isichei, Elizabeth (1997). A History of African Societies to 1870. Cambridge Universitas Press. p. 234. ISBN 0-521-45599-5.

- Okehie-Offoha, Marcellina; Matthew N. O. Sadiku (December 1995). Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Nigeria. Africa World Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-86543-283-3.

- Britannica, Kano, britannica.com, USA, accessed on July 7, 2019

- "Kano". Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

- Ki-Zerbo, Joseph (1998). UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. IV, Abridged Edition: Africa from the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century. University of California Press. p. 107. ISBN 0-520-06699-5.

- "Caravans Across the Desert: Marketplace". AFRICA: One Continent. Many Worlds. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Foundation. Archived from the original on January 2, 2005. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

- "50 Greatest Africans – Sarki Muhammad Rumfa & Emperor Semamun". When We Ruled. Every Generation Media. Retrieved 2007-05-05.

- Nast, p. 61

- Lovejoy, Paul (1983). Transformations in Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 195. ISBN 0-521-24369-6.

- Milich, Lee (1997-07-17). "Food Security in Pre-Colonial Hausaland". College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. Retrieved 2007-10-26.

- Stilwell, Sean (2000). "Power, Honour and Shame: The Ideology of Royal Slavery in the Sokoto Caliphate". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. Edinburgh University Press. 70 (3): 394–421. doi:10.2307/1161067. JSTOR 1161067.

- Christelow, Allan (1987). "Property and Theft in Kano at the Dawn of the Groundnut Boom, 1912–1914". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. Boston University African Studies Center. 20 (2): 225–243. doi:10.2307/219841. JSTOR 219841.

- Dan-Asabe, Abdulkarim Umar (November 2000). "Biography of Select Kano Merchants, 1853–1955". FAIS Journal of Humanities. 1 (2). Archived from the original (Scholar search) on October 9, 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-09.

- Ernest E. Uwazie; Isaac Olawale Albert; G. N. Uzoigwe (1999). "The Role of Communication in the Escalation of Ethnic and Religious Conflicts". Inter-Ethnic and Religious Conflict Resolution in Nigeria. Lexington Books. p. 20. ISBN 0-7391-0033-5.

- Uwazie et al., p. 73

- Gambari, Ibrahim (1992). "The Role of Religion in National Life: Reflections on Recent Experiences in Nigeria". In Hunwick, John Owen (ed.). Religion and National Integration in Africa: Islam, Christianity and Politics in the Sudan and Nigeria. Northwestern University Press. p. 90. ISBN 0-8101-1037-7.

- "Nigeria's Kano state celebrates Sharia". BBC News. 2000-06-21. Retrieved 2007-11-04.

- Obasanjo Assesses Riot Damage in Kano – 2001-10-16. Voice of America News.

- "Kano: Nigeria's ancient city-state". BBC online. BBC. 2004-05-20. Retrieved 2007-07-12.

- "Army patrols Kano after clashes". News.BBC.com. BBC News. 2007-11-21. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- Karofi, Hassan A; Halima Musa (2007-11-21). "ANPP Sweeps Kano LG Polls". Daily Trust online. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- Shuaibu, Ibrahim (2007-11-21). "Kano Death Toll Rises to 25". Thisday online. Leaders & Company. Archived from the original on 2007-12-01. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- "Nigeria violence: Scores dead after Kano blasts". BBC News. 2012-01-21. Retrieved 2012-01-22.

- News Desk. "Many Dead Following Bomb Blasts in Kano, Nigeria". The Global Herald.

- "World Weather Information Service – Kano". World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- "Kano Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- J. Gordon Melton, Martin Baumann, ‘‘Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices’’, ABC-CLIO, USA, 2010, p. 2107

- "Trains in Nigeria: A slow but steady new chug," The Economist

- "ZTE COMMUNICATIONS FOR NIGERIA'S RAILWAY". Railways Africa. Archived from the original on 9 June 2014.

- "Kano light rail contract signed". Metro Report. 17 February 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- "Nigeria to build a light rail system in Kano". Railway Pro. 2 September 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- Barau, A.S. (2007) The Great Attractions of Kano.

- "About Ado Bayero Mall". www.adobayeromall.com. Retrieved 2016-01-26.

- "Kano". Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2007.

- "Nigerian city of Kano plans IT park". Panapress. Afriquenligne. 2007-11-04. Archived from the original on 2008-02-11. Retrieved 2007-11-04.

- PROF. ABDU SALIHI, FNSE (May 11–12, 2009). "Hydropower Development at Tiga and Challawa Gorge Dams, Kano State, Nigeria" (PDF). International Network on Small Hydro Power (IN-SHP). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-26. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

- "Contact Us." Kabo Air. Retrieved on 27 November 2010. "HEAD OFFICE 67/73 Ashton Rd P.O.Box 1850 Kano State Nigeria"

Further reading

- See also: Bibliography of the history of Kano

- Maconachie, Roy (2007). Urban Growth and Land Degradation in Developing Cities: Change and Challenges in Kano, Nigeria. King's SOAS Studies in Development Geography. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-4828-4.

- Barau, Aliyu Salisu (2007). The Great Attractions of Kano. Research and Documentation publications. Research and Documentation Directorate, Government House Kano. ISBN 978-8109-33-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kano. |

| Wikisource has the text of the Encyclopaedia Britannica (9th ed.) article Kano. |

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.