Palm oil

Palm oil is an edible vegetable oil derived from the mesocarp (reddish pulp) of the fruit of the oil palms, primarily the African oil palm Elaeis guineensis,[1] and to a lesser extent from the American oil palm Elaeis oleifera and the maripa palm Attalea maripa.

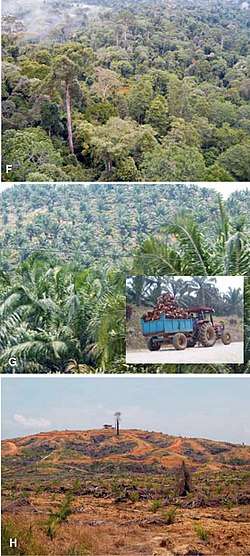

The use of palm oil in food products has attracted the concern of environmental groups; the high oil yield of the trees has encouraged wider cultivation, leading to the clearing of forests in parts of Indonesia to make space for oil-palm monoculture.[2] This has resulted in significant acreage losses of the natural habitat of the three surviving species of orangutan. One species in particular, the Sumatran orangutan, has been listed as critically endangered.[3][4]

History

Humans used oil palms as far back as 5,000 years. In the late 1800s, archaeologists discovered a substance that they concluded was originally palm oil in a tomb at Abydos dating back to 3,000 BCE.[5] It is believed that traders brought oil palm to Egypt.

Palm oil from E. guineensis has long been recognized in West and Central African countries, and is widely used as a cooking oil. European merchants trading with West Africa occasionally purchased palm oil for use as a cooking oil in Europe.

Palm oil became a highly sought-after commodity by British traders for use as an industrial lubricant for machinery during Britain's Industrial Revolution.[6]

Palm oil formed the basis of soap products, such as Lever Brothers' (now Unilever) "Sunlight" soap, and the American Palmolive brand.[7]

By around 1870, palm oil constituted the primary export of some West African countries, although this was overtaken by cocoa in the 1880s with the introduction of colonial European cocoa plantations.[8][9]

Composition

Fatty acids

Palm oil, like all fats, is composed of fatty acids, esterified with glycerol. Palm oil has an especially high concentration of saturated fat, specifically the 16-carbon saturated fatty acid, palmitic acid, to which it gives its name. Monounsaturated oleic acid is also a major constituent of palm oil. Unrefined palm oil is a significant source of tocotrienol, part of the vitamin E family.[10][11]

The approximate concentration of esterified fatty acids in palm oil is:[12]

Carotenes

Red palm oil is rich in carotenes, such as alpha-carotene, beta-carotene and lycopene, which give it a characteristic dark red color.[11][13] However, palm oil that has been refined, bleached and deodorized from crude palm oil (called "RBD palm oil") does not contain carotenes.[14]

Comparison to other vegetable oils

| Type | Processing treatment | Saturated fatty acids | Monounsaturated fatty acids | Polyunsaturated fatty acids | Smoke point | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total[15] | Oleic acid (ω-9) | Total[15] | α-Linolenic acid (ω-3) | Linoleic acid (ω-6) | ω-6:3 ratio | ||||

| Almond oil | |||||||||

| Avocado[17] | 11.6 | 70.6 | 52-66[18] | 13.5 | 1 | 12.5 | 12.5:1 | 250 °C (482 °F)[19] | |

| Brazil nut[20] | 24.8 | 32.7 | 31.3 | 42.0 | 0.1 | 41.9 | 419:1 | 208 °C (406 °F)[21] | |

| Canola[22] | 7.4 | 63.3 | 61.8 | 28.1 | 9.1 | 18.6 | 2:1 | 238 °C (460 °F)[21] | |

| Cashew oil | |||||||||

| Chia seeds | |||||||||

| Cocoa butter oil | |||||||||

| Coconut[23] | 82.5 | 6.3 | 6 | 1.7 | 175 °C (347 °F)[21] | ||||

| Corn[24] | 12.9 | 27.6 | 27.3 | 54.7 | 1 | 58 | 58:1 | 232 °C (450 °F)[25] | |

| Cottonseed[26] | 25.9 | 17.8 | 19 | 51.9 | 1 | 54 | 54:1 | 216 °C (420 °F)[25] | |

| Flaxseed/Linseed[27] | 9.0 | 18.4 | 18 | 67.8 | 53 | 13 | 0.2:1 | 107 °C (225 °F) | |

| Grape seed | 10.5 | 14.3 | 14.3 | 74.7 | - | 74.7 | very high | 216 °C (421 °F)[28] | |

| Hemp seed[29] | 7.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 82.0 | 22.0 | 54.0 | 2.5:1 | 166 °C (330 °F)[30] | |

| Vigna mungo | |||||||||

| Mustard oil | |||||||||

| Olive[31] | 13.8 | 73.0 | 71.3 | 10.5 | 0.7 | 9.8 | 14:1 | 193 °C (380 °F)[21] | |

| Palm[32] | 49.3 | 37.0 | 40 | 9.3 | 0.2 | 9.1 | 45.5:1 | 235 °C (455 °F) | |

| Peanut[33] | 20.3 | 48.1 | 46.5 | 31.5 | 0 | 31.4 | very high | 232 °C (450 °F)[25] | |

| Pecan oil | |||||||||

| Perilla oil | |||||||||

| Rice bran oil | |||||||||

| Safflower[34] | 7.5 | 75.2 | 75.2 | 12.8 | 0 | 12.8 | very high | 212 °C (414 °F)[21] | |

| Sesame[35] | ? | 14.2 | 39.7 | 39.3 | 41.7 | 0.3 | 41.3 | 138:1 | |

| Soybean[36] | Partially hydrogenated | 14.9 | 43.0 | 42.5 | 37.6 | 2.6 | 34.9 | 13.4:1 | |

| Soybean[37] | 15.6 | 22.8 | 22.6 | 57.7 | 7 | 51 | 7.3:1 | 238 °C (460 °F)[25] | |

| Walnut oil | |||||||||

| Sunflower (standard)[38] | 10.3 | 19.5 | 19.5 | 65.7 | 0 | 65.7 | very high | 227 °C (440 °F)[25] | |

| Sunflower (< 60% linoleic)[39] | 10.1 | 45.4 | 45.3 | 40.1 | 0.2 | 39.8 | 199:1 | ||

| Sunflower (> 70% oleic)[40] | 9.9 | 83.7 | 82.6 | 3.8 | 0.2 | 3.6 | 18:1 | 232 °C (450 °F)[41] | |

| Cottonseed[42] | Hydrogenated | 93.6 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.5:1 | ||

| Palm[43] | Hydrogenated | 88.2 | 5.7 | 0 | |||||

| The nutritional values are expressed as percent (%) by weight of total fat. | |||||||||

Processing and use

Palm oil is naturally reddish in color because of a high beta-carotene content. It is not to be confused with palm kernel oil derived from the kernel of the same fruit[44] or coconut oil derived from the kernel of the coconut palm (Cocos nucifera). The differences are in color (raw palm kernel oil lacks carotenoids and is not red), and in saturated fat content: palm mesocarp oil is 49% saturated, while palm kernel oil and coconut oil are 81% and 86% saturated fats, respectively. However, crude red palm oil that has been refined, bleached and deodorized, a common commodity called RBD (refined, bleached, and deodorized) palm oil, does not contain carotenoids.[14] Many industrial food applications of palm oil use fractionated components of palm oil (often listed as "modified palm oil") whose saturation levels can reach 90%;[45] these "modified" palm oils can become highly saturated, but are not necessarily hydrogenated.

The oil palm produces bunches containing many fruits with the fleshy mesocarp enclosing a kernel that is covered by a very hard shell. The FAO considers palm oil (coming from the pulp) and palm kernels to be primary products. The oil extraction rate from a bunch varies from 17 to 27% for palm oil, and from 4 to 10% for palm kernels.[46]

Along with coconut oil, palm oil is one of the few highly saturated vegetable fats and is semisolid at room temperature.[47] Palm oil is a common cooking ingredient in the tropical belt of Africa, Southeast Asia and parts of Brazil. Its use in the commercial food industry in other parts of the world is widespread because of its lower cost[48] and the high oxidative stability (saturation) of the refined product when used for frying.[49][50] One source reported that humans consumed an average 17 pounds (7.7 kg) of palm oil per person in 2015.[51]

Many processed foods either contain palm oil or various ingredients made from it.[52]

Refining

After milling, various palm oil products are made using refining processes. First is fractionation, with crystallization and separation processes to obtain solid (palm stearin), and liquid (olein) fractions.[53] Then melting and degumming removes impurities. Then the oil is filtered and bleached. Physical refining removes smells and coloration to produce "refined, bleached and deodorized palm oil" (RBDPO) and free fatty acids, which are used in the manufacture of soaps, washing powder and other products. RBDPO is the basic palm oil product sold on the world's commodity markets. Many companies fractionate it further to produce palm oil for cooking oil, or process it into other products.[53]

Red palm oil

Since the mid-1990s, red palm oil has been cold-pressed from the fruit of the oil palm and bottled for use as a cooking oil, in addition to other uses such as being blended into mayonnaise and vegetable oil.[14]

Oil produced from palm fruit is called red palm oil or just palm oil. It is around 50% saturated fat—considerably less than palm kernel oil—and 40% unsaturated fat and 10% polyunsaturated fat. In its unprocessed state, red palm oil has an intense deep red color because of its abundant carotene content. Like palm kernel oil, red palm oil contains around 50% medium chain fatty acids, but it also contains the following nutrients:[54]

- Carotenoids, such as alpha-carotene, beta-carotene, and lycopene

- Sterols

- Vitamin E

White palm oil

White palm oil is the result of processing and refining. When refined, the palm oil loses its deep red color. It is extensively used in food manufacture and can be found in a variety of processed foods including peanut butter and chips. It is often labeled as palm shortening and is used as a replacement ingredient for hydrogenated fats in a variety of baked and fried products.

Use in food

The highly saturated nature of palm oil renders it solid at room temperature in temperate regions, making it a cheap substitute for butter or hydrogenated vegetable oils in uses where solid fat is desirable, such as the making of pastry dough and baked goods. The health concerns related to trans fats in hydrogenated vegetable oils may have contributed to the increasing use of palm oil in the food industry.[55]

Palm oil is also used in animal feed. In March 2017, a documentary made by Deutsche Welle revealed that palm oil is used to make milk substitutes to feed calves in dairies in the German alps. These milk substitutes contain 30% milk powder and the remainder of raw protein made from skimmed milk powder, whey powder, and vegetable fats, mostly coconut oil and palm oil.[56]

Biomass and biofuels

Palm oil is used to produce both methyl ester and hydrodeoxygenated biodiesel.[57] Palm oil methyl ester is created through a process called transesterification. Palm oil biodiesel is often blended with other fuels to create palm oil biodiesel blends.[58] Palm oil biodiesel meets the European EN 14214 standard for biodiesels.[57] Hydrodeoxygenated biodiesel is produced by direct hydrogenolysis of the fat into alkanes and propane. The world's largest palm oil biodiesel plant is the €550 million Finnish-operated Neste Oil biodiesel plant in Singapore, which opened in 2011 with a capacity of 800,000 tons per year and produces hydrodeoxygenated NEXBTL biodiesel from palm oil imported from Malaysia and Indonesia.[59][60]

Significant amounts of palm oil exports to Europe are converted to biodiesel (as of early 2018: Indonesia: 40%, Malaysia 30%).[61][62] In 2014, almost half of all the palm oil in Europe was burnt as car and truck fuel.[63] As of 2018, one-half of Europe's palm oil imports were used for biodiesel.[64] Use of palm oil as biodiesel generates three times the carbon emissions as using fossil fuel,[65] and, for example, "biodiesel made from Indonesian palm oil makes the global carbon problem worse, not better."[66]

The organic waste matter that is produced when processing oil palm, including oil palm shells and oil palm fruit bunches, can also be used to produce energy. This waste material can be converted into pellets that can be used as a biofuel.[67] Additionally, palm oil that has been used to fry foods can be converted into methyl esters for biodiesel. The used cooking oil is chemically treated to create a biodiesel similar to petroleum diesel.[68]

In wound care

Although palm oil is applied to wounds for its supposed antimicrobial effects, research does not confirm its effectiveness.[69]

Production

In 2016, the global production of palm oil was estimated at 62.6 million tonnes, 2.7 million tonnes more than in 2015. The palm oil production value was estimated at $US39.3 billion in 2016, an increase of $US2.4 billion (or +7%) against the production figure recorded in the previous year.[70] Between 1962 and 1982 global exports of palm oil increased from around half a million to 2.4 million tonnes annually and in 2008 world production of palm oil and palm kernel oil amounted to 48 million tonnes. According to FAO forecasts by 2020 the global demand for palm oil will double, and triple by 2050.[71]

In 2018–2019 world production of palm oil 73.5 mln tonnes [72]

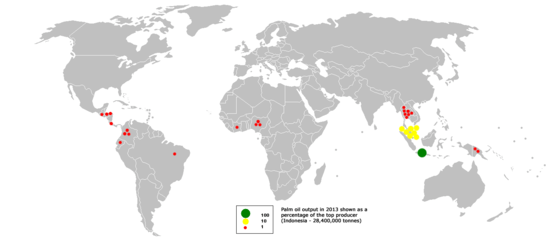

Indonesia

Indonesia is the world's largest producer of palm oil, surpassing Malaysia in 2006, producing more than 20.9 million tonnes,[73][74] a number that has since risen to over 34.5 million tons (2016 output). Indonesia expects to double production by the end of 2030.[4] At the end of 2010, 60% of the output was exported in the form of crude palm oil.[75] FAO data shows production increased by over 400% between 1994 and 2004, to over 8.7 million metric tonnes.

Malaysia

Malaysia is the world's second largest producer of palm oil. In 1992, in response to concerns about deforestation, the Government of Malaysia pledged to limit the expansion of palm oil plantations by retaining a minimum of half the nation's land as forest cover.[76][77]

In 2012, [78] produced 18.8 million tonnes of crude palm oil on roughly 5,000,000 hectares (19,000 sq mi) of land.[79][80] Though Indonesia produces more palm oil, Malaysia is the world's largest exporter of palm oil having exported 18 million tonnes of palm oil products in 2011. India, China, Pakistan, the European Union and the United States are the primary importers of Malaysian palm oil products.[81] Palm oil prices jumped to a four-year high days after Trump's election victory.[82]

Nigeria

As of 2018, Nigeria was the third-largest producer, with approximately 2.3 million hectares (5.7×106 acres) under cultivation. Until 1934, Nigeria had been the world's largest producer. Both small- and large-scale producers participated in the industry.[83][84]

Thailand

Thailand is the world's third largest producer of crude palm oil, producing approximately two million tonnes per year, or 1.2% of global output. Nearly all of Thai production is consumed locally. Almost 85% of palm plantations and extraction mills are in south Thailand. At year-end 2016, 4.7 to 5.8 million rai were planted in oil palms, employing 300,000 farmers, mostly on small landholdings of 20 rai. ASEAN as a region accounts for 52.5 million tonnes of palm oil production, about 85% of the world total and more than 90% of global exports. Indonesia accounts for 52% of world exports. Malaysian exports total 38%. The biggest consumers of palm oil are India, the European Union, and China, with the three consuming nearly 50% of world exports. Thailand's Department of Internal Trade (DIT) usually sets the price of crude palm oil and refined palm oil Thai farmers have a relatively low yield compared to those in Malaysia and Indonesia. Thai palm oil crops yield 4–17% oil compared to around 20% in competing countries. In addition, Indonesian and Malaysian oil palm plantations are 10 times the size of Thai plantations.[85]

Colombia

In the 1960s, about 18,000 hectares (69 sq mi) were planted with palm. Colombia has now become the largest palm oil producer in the Americas, and 35% of its product is exported as biofuel. In 2006, the Colombian plantation owners' association, Fedepalma, reported that oil palm cultivation was expanding to 1,000,000 hectares (3,900 sq mi). This expansion is being funded, in part, by the United States Agency for International Development to resettle disarmed paramilitary members on arable land, and by the Colombian government, which proposes to expand land use for exportable cash crops to 7,000,000 hectares (27,000 sq mi) by 2020, including oil palms. Fedepalma states that its members are following sustainable guidelines.[86]

Some Afro-Colombians claim that some of these new plantations have been expropriated from them after they had been driven away through poverty and civil war, while armed guards intimidate the remaining people to further depopulate the land, with coca production and trafficking following in their wake.[87]

Ecuador

Ecuador aims to help palm oil producers switch to sustainable methods and achieve RSPO certification under initiatives to develop greener industries.[88]

Other countries

Benin

Palm is native to the wetlands of western Africa, and south Benin already hosts many palm plantations. Its 'Agricultural Revival Programme' has identified many thousands of hectares of land as suitable for new oil palm export plantations. In spite of the economic benefits, Non-governmental organisations (NGOs), such as Nature Tropicale, claim biofuels will compete with domestic food production in some existing prime agricultural sites. Other areas comprise peat land, whose drainage would have a deleterious environmental impact. They are also concerned genetically modified plants will be introduced into the region, jeopardizing the current premium paid for their non-GM crops.[89][90]

Cameroon

Cameroon had a production project underway initiated by Herakles Farms in the US.[91] However, the project was halted under the pressure of civil society organizations in Cameroon. Before the project was halted, Herakles left the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil early in negotiations.[92] The project has been controversial due to opposition from villagers and the location of the project in a sensitive region for biodiversity.

Kenya

Kenya's domestic production of edible oils covers about a third of its annual demand, estimated at around 380,000 tonnes. The rest is imported at a cost of around US$140 million a year, making edible oil the country's second most important import after petroleum. Since 1993 a new hybrid variety of cold-tolerant, high-yielding oil palm has been promoted by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations in western Kenya. As well as alleviating the country's deficit of edible oils while providing an important cash crop, it is claimed to have environmental benefits in the region, because it does not compete against food crops or native vegetation and it provides stabilisation for the soil.[93]

Ghana

Ghana has a lot of palm nut species, which may become an important contributor to the agriculture of the region. Although Ghana has multiple palm species, ranging from local palm nuts to other species locally called agric, it was only marketed locally and to neighboring countries. Production is now expanding as major investment funds are purchasing plantations, because Ghana is considered a major growth area for palm oil.

Social and environmental impacts

Social

The palm oil industry has had both positive and negative impacts on workers, indigenous peoples and residents of palm oil-producing communities. Palm oil production provides employment opportunities, and has been shown to improve infrastructure, social services and reduce poverty.[94][95][96] However, in some cases, oil palm plantations have developed lands without consultation or compensation of the indigenous people inhabiting the land, resulting in social conflict.[97][98][99] The use of illegal immigrants in Malaysia has also raised concerns about working conditions within the palm oil industry.[100][101][102]

Some social initiatives use palm oil cultivation as part of poverty alleviation strategies. Examples include the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation's hybrid oil palm project in Western Kenya, which improves incomes and diets of local populations,[103] and Malaysia's Federal Land Development Authority and Federal Land Consolidation and Rehabilitation Authority, which both support rural development.[104]

Food vs. fuel

The use of palm oil in the production of biodiesel has led to concerns that the need for fuel is being placed ahead of the need for food, leading to malnutrition in developing nations. This is known as the food versus fuel debate. According to a 2008 report published in the Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, palm oil was determined to be a sustainable source of both food and biofuel. The production of palm oil biodiesel does not pose a threat to edible palm oil supplies.[105] According to a 2009 study published in the Environmental Science and Policy journal, palm oil biodiesel might increase the demand for palm oil in the future, resulting in the expansion of palm oil production, and therefore an increased supply of food.[106]

Environmental

While only 5% of the world's vegetable oil farmland is used for palm plantations, palm cultivation produces 38% of the world's total vegetable oil supply.[107] In terms of oil yield, a palm plantation is 10 times more productive than soybean, sunflower or rapeseed cultivation because the palm fruit and kernel both provide usable oil.[107] Palm oil is the most sustainable vegetable oil in terms of yield, requiring one-ninth of land used by other vegetable oil crops,[108] but in the future laboratory-grown microbes might achieve higher yields per unit of land at comparable prices.[109][110]

However palm oil cultivation has been criticized for its impact on the natural environment,[111][112] including deforestation, loss of natural habitats,[113] and greenhouse gas emissions[114][115] which have threatened critically endangered species, such as the orangutan[116] and Sumatran tiger.[117]

Environmental groups such as Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth oppose the use of palm oil biofuels, claiming that the deforestation caused by oil palm plantations is more damaging for the climate than the benefits gained by switching to biofuel and using the palms as carbon sinks.[118]

A 2018 study by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) concluded that palm oil is "here to stay" due to its higher productivity compared with many other vegetable oils. The IUCN maintains that replacing palm oil with other vegetable oils would necessitate greater amounts of agricultural land, negatively affecting biodiversity.[108][119] The IUCN advocates better practices in the palm oil industry, including the prevention of plantations from expanding into forested regions and creating a demand for certified and sustainable palm oil products.[119]

In 2019 the Rainforest Action Network surveyed eight global brands involved in palm oil extraction in the Leuser Ecosystem, and said that none was performing adequately in avoiding “conflict palm oil”.[120] Many of the companies told the Guardian they were working to improve their performance.[121] A WWF scorecard rated only 15 out of 173 companies as performing well.[122]

Markets

According to the Hamburg-based Oil World trade journal,[123] in 2008 global production of oils and fats stood at 160 million tonnes. Palm oil and palm kernel oil were jointly the largest contributor, accounting for 48 million tonnes, or 30% of the total output. Soybean oil came in second with 37 million tonnes (23%). About 38% of the oils and fats produced in the world were shipped across oceans. Of the 60 million tonnes of oils and fats exported around the world, palm oil and palm kernel oil made up close to 60%; Malaysia, with 45% of the market share, dominated the palm oil trade.

Food label regulations

Previously, palm oil could be listed as "vegetable fat" or "vegetable oil" on food labels in the European Union (EU). From December 2014, food packaging in the EU is no longer allowed to use the generic terms "vegetable fat" or "vegetable oil" in the ingredients list. Food producers are required to list the specific type of vegetable fat used, including palm oil. Vegetable oils and fats can be grouped together in the ingredients list under the term "vegetable oils" or "vegetable fats" but this must be followed by the type of vegetable origin (e.g., palm, sunflower, or rapeseed) and the phrase "in varying proportions".[124]

Supply chain institutions

Consumer Goods Forum

In 2010 the Consumer Goods Forum passed a resolution that its members would reduce deforestation through their palm oil supply to net zero by 2020.[125]

Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO)

The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) was established in 2004[126] following concerns raised by non-governmental organizations about environmental impacts resulting from palm oil production. The organization has established international standards for sustainable palm oil production.[127] Products containing Certified Sustainable Palm Oil (CSPO) can carry the RSPO trademark.[128] Members of the RSPO include palm oil producers, environmental groups, and manufacturers who use palm oil in their products.[126][127]

The RSPO is applying different types of programmes to supply palm oil to producers.[129]

- Book and claim: no guarantee that the end product contains certified sustainable palm oil, supports RSPO-certified growers and farmers

- Identity preserved: the end user is able to trace the palm oil back to a specific single mill and its supply base (plantations)

- Segregated: this option guarantees that the end product contains certified palm oil

- Mass balance: the refinery is only allowed to sell the same amount of mass balance palm oil as the amount of certified sustainable palm oil purchased

GreenPalm is one of the retailers executing the book and claim supply chain and trading programme. It guarantees that the palm oil producer is certified by the RSPO. Through GreenPalm the producer can certify a specified amount with the GreenPalm logo. The buyer of the oil is allowed to use the RSPO and the GreenPalm label for sustainable palm oil on their products.[129]

After the meeting in 2009 a number of environmental organisations were critical of the scope of the agreements reached.[126] Palm oil growers who produce CSPO have been critical of the organization because, though they have met RSPO standards and assumed the costs associated with certification, the market demand for certified palm oil remains low.[127][128] Low market demand has been attributed to the higher cost of CSPO, leading palm oil buyers to purchase cheaper non-certified palm oil. Palm oil is mostly fungible. In 2011, 12% of palm oil produced was certified "sustainable", though only half of that had the RSPO label.[130] Even with such a low proportion being certified, Greenpeace has argued that confectioners are avoiding responsibilities on sustainable palm oil, because it says that RSPO standards fall short of protecting the environment.[131]

Nutrition and health

Contributing significant calories as a source of fat, palm oil is a food staple in many cuisines.[132][133][134] On average globally, humans consumed 7.7 kg (17 lb) of palm oil per person in 2015.[51] Although the relationship of palm oil consumption to disease risk has been previously assessed, the quality of the clinical research specifically assessing palm oil effects has been generally poor.[135] Consequently, research has focused on the deleterious effects of palm oil and palmitic acid consumption as sources of saturated fat content in edible oils, leading to conclusions that palm oil and saturated fats should be replaced with polyunsaturated fats in the diet.[136][137]

A 2015 meta-analysis and 2017 advisory from the American Heart Association indicated that palm oil is among foods supplying dietary saturated fat which increases blood levels of LDL cholesterol and increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, leading to recommendations for reduced use or elimination of dietary palm oil in favor of consuming unhydrogenated vegetable oils.[138][139]

Palmitic acid

Excessive intake of palmitic acid, which makes up 44% of palm oil, increases blood levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and total cholesterol, and so increases risk of cardiovascular diseases.[136][137][140] Other reviews, the World Health Organization, and the US National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute have encouraged consumers to limit the consumption of palm oil, palmitic acid and foods high in saturated fat.[132][136][140][141]

References

- Reeves, James B.; Weihrauch, John L; Consumer and Food Economics Institute (1979). Composition of foods: fats and oils. Agriculture handbook 8-4. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Science and Education Administration. p. 4. OCLC 5301713.

- "Deforestation". www.sustainablepalmoil.org. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; Pongo abelii. "Archived copy". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Archived from the original on 18 November 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). Accessed: 2016-04-22

- Natasha Gilbert (4 July 2012). "Palm-oil boom raises conservation concerns: Industry urged towards sustainable farming practices as rising demand drives deforestation". Nature. 487 (7405): 14–15. doi:10.1038/487014a. PMID 22763524.

- Kiple, Kenneth F.; Conee Ornelas, Kriemhild, eds. (2000). The Cambridge World History of Food. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521402163. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- "British Colonial Policies and the Oil Palm Industry in the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria, 1900–1960" (PDF). African Study Monographs. 21 (1): 19–33. 2000. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 January 2013.

- Bellis, Mary. "The History of Soaps and Detergents". About.com.

In 1864, Caleb Johnson founded a soap company called B.J. Johnson Soap Co., in Milwaukee. In 1898, this company introduced a soap made of palm and olive oils called Palmolive.

- "antislavery.org" (PDF).

- Commercial Agriculture, the Slave Trade and Slavery in Atlantic Africa ISBN 978-1-847-01075-9 p. 22

- Ahsan H, Ahad A, Siddiqui WA (2015). "A review of characterization of tocotrienols from plant oils and foods". J Chem Biol. 8 (2): 45–59. doi:10.1007/s12154-014-0127-8. PMC 4392014. PMID 25870713.

- Oi-Ming Lai, Chin-Ping Tan, Casimir C. Akoh (Editors) (2015). Palm Oil: Production, Processing, Characterization, and Uses. Elsevier. pp. 471, Chap. 16. ISBN 978-0128043462.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "Oil, vegetable, palm per 100 g; Fats and fatty acids". Conde Nast for the USDA National Nutrient Database, Release SR-21. 2014. Archived from the original on 28 October 2016. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- Ng, M. H.; Choo, Y. M. (2016). "Improved Method for the Qualitative Analyses of Palm Oil Carotenes Using UPLC". Journal of Chromatographic Science. 54 (4): 633–638. doi:10.1093/chromsci/bmv241. PMC 4885407. PMID 26941414.

- Nagendran, B.; Unnithan, U. R.; Choo, Y. M.; Sundram, Kalyana (2000). "Characteristics of red palm oil, a carotene- and vitamin E–rich refined oil for food uses". Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 21 (2): 77–82. doi:10.1177/156482650002100213.

- "US National Nutrient Database, Release 28". United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. All values in this table are from this database unless otherwise cited.

- "Fats and fatty acids contents per 100 g (click for "more details"). Example: Avocado oil (user can search for other oils)". Nutritiondata.com, Conde Nast for the USDA National Nutrient Database, Standard Release 21. 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2017. Values from Nutritiondata.com (SR 21) may need to be reconciled with most recent release from the USDA SR 28 as of Sept 2017.

- "Avocado oil, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- Feramuz Ozdemir; Ayhan Topuz (May 2003). "Changes in dry matter, oil content and fatty acids composition of avocado during harvesting time and post-harvesting ripening period" (PDF). Elsevier. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- Marie Wong; Cecilia Requejo-Jackman; Allan Woolf (April 2010). "What is unrefined, extra virgin cold-pressed avocado oil?". Aocs.org. The American Oil Chemists’ Society. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- "Brazil nut oil, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- Katragadda, H. R.; Fullana, A. S.; Sidhu, S.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á. A. (2010). "Emissions of volatile aldehydes from heated cooking oils". Food Chemistry. 120: 59–65. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.09.070.

- "Canola oil, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Coconut oil, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Corn oil, industrial and retail, all purpose salad or cooking, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- Wolke, Robert L. (16 May 2007). "Where There's Smoke, There's a Fryer". The Washington Post. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- "Cottonseed oil, salad or cooking, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Linseed/Flaxseed oil, cold pressed, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- Garavaglia J, Markoski MM, Oliveira A, Marcadenti A (2016). "Grape Seed Oil Compounds: Biological and Chemical Actions for Health". Nutr Metab Insights. 9: 59–64. doi:10.4137/NMI.S32910. PMC 4988453. PMID 27559299.

- Callaway, J.; Schwab, U.; Harvima, I.; Halonen, P.; Mykkänen, O.; Hyvönen, P.; Järvinen, T. (2005). "Efficacy of dietary hempseed oil in patients with atopic dermatitis". Journal of Dermatological Treatment. 16 (2): 87–94. doi:10.1080/09546630510035832. PMID 16019622.

- "Smoke points of oils" (PDF).

- "Olive oil, salad or cooking, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Palm oil, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- Vegetable Oils in Food Technology (2011), p. 61.

- "Safflower oil, salad or cooking, high oleic, primary commerce, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Soybean oil". FoodData Central. fdc.nal.usda.gov.

- "Soybean oil, salad or cooking, (partially hydrogenated), fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Soybean oil, salad or cooking, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Sunflower oil, 65% linoleic, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- "Sunflower oil, less than 60% of total fats as linoleic acid, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Sunflower oil, high oleic - 70% or more as oleic acid, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Smoke Point of Oils". Baseline of Health. Jonbarron.org. 17 April 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- "Cottonseed oil, industrial, fully hydrogenated, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Palm oil, industrial, fully hydrogenated, filling fat, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- Poku, Kwasi (2002). "Origin of oil palm". Small-Scale Palm Oil Processing in Africa. FAO Agricultural Services Bulletin 148. Food and Agriculture Organization. ISBN 978-92-5-104859-7. Archived from the original on 23 September 2009.

- Gibon, Véronique (2012). "Palm Oil and Palm Kernel Oil Refining and Fractionation Technology". Palm Oil. pp. 329–375. doi:10.1016/B978-0-9818936-9-3.50015-0. ISBN 9780981893693.

This super stearin contains ∼90% of saturated fatty acids, predominantly palmitic ...

- "FAO data – dimension-member – Oil, palm fruit". ref.data.fao.org. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- Behrman, E. J.; Gopalan, Venkat (2005). William M. Scovell (ed.). "Cholesterol and Plants" (PDF). Journal of Chemical Education. 82 (12): 1791. Bibcode:2005JChEd..82.1791B. doi:10.1021/ed082p1791. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 October 2012.

- "Palm Oil Continues to Dominate Global Consumption in 2006/07" (PDF) (Press release). United States Department of Agriculture. June 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2009.

- Che Man, YB; Liu, J.L.; Jamilah, B.; Rahman, R. Abdul (1999). "Quality changes of RBD palm olein, soybean oil and their blends during deep-fat frying". Journal of Food Lipids. 6 (3): 181–193. doi:10.1111/j.1745-4522.1999.tb00142.x.

- Matthäus, Bertrand (2007). "Use of palm oil for frying in comparison with other high-stability oils". European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology. 109 (4): 400–409. doi:10.1002/ejlt.200600294.

- Raghu, Anuradha (17 May 2017). "We Each Consume 17 Pounds of Palm Oil a Year". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- "Palm oil products and the weekly shop". BBC Panorama. 22 February 2010. Archived from the original on 25 February 2010. Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- "Investment in Technology". PT. Asianagro Agungjaya. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007.

- Oguntibeju, O.O; Esterhuyse, A.J.; Truter, E.J. (2009). "Red palm oil: nutritional, physiological and therapeutic roles in improving human wellbeing and quality of life". British Journal of Biomedical Science. 66 (4): 216–22. doi:10.1080/09674845.2009.11730279. PMID 20095133.

- "Palm Oil In The Food Supply: What You Should Know". NPR.org. 25 July 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- "Too much milk in Europe (Interview with Sprayfo)". Deutsche Welle. 25 March 2017.

- Rojas, Mauricio (3 August 2007). "Assessing the Engine Performance of Palm Oil Biodiesel". Biodiesel Magazine. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- Nahian, Md. Rafsan; Islam, Md. Nurul; Khan, Shaheen (26 December 2016). "Production of Biodiesel from Palm Oil and Performance Test with Diesel in CI Engine". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Yahya, Yasmine (9 March 2011). "World's Largest Biodiesel Plant Opens in Singapore". The Jakarta Globe. Archived from the original on 26 June 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- Tuck, Andrew, ed. (July 2011). "Neste Oil_". Monocle. 05 (45): 73. ISSN 1753-2434.

Petri Jokinen (right), managing director of Neste Oil Singapore [...] the €550m plant has an annual production capacity of 800,000 metric tons of NExBTL renewable diesel, which is distributed mainly in Europe [...] palm oil, is imported from neighbouring Malaysia and Indonesia

- hermes (24 January 2018). "European ban on palm oil in biofuels upsets Jakarta, KL". The Straits Times.

- Wahyudi Soeriaatmadja; Trinna Leong (24 January 2018). "European ban on palm oil in biofuels upsets Jakarta, KL". The Straits Times. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

For Indonesia, 40% of its palm oil exports to Europe are converted into biofuels. Europe is Malaysia's second-largest export market for palm oil, with 30% of it used for biodiesel.

- Melanie Hall (1 June 2016). "New palm oil figures: Biodiesel use in EU fueling deforestation". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

In 2014, nearly half of the palm oil used in Europe ended up in the gas tanks of cars and trucks, according to data compiled by the EU vegetable oil industry association Fediol

- Robert-Jan Bartunek; Alissa de Carbonnel (14 June 2018). "EU to phase out palm oil from transport fuel by 2030". Reuters. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

Half of the EU’s 6 billion euros ($7 billion) worth of palm oil imports are used for biodiesel, according to data from Copenhagen Economics.

- Hans Spross (22 June 2018). "Does EU biofuel deal compromise the environment for trade with Southeast Asia?". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

According to a 2015 study carried out on behalf of the European Commission, the production and use of palm oil biodiesel causes three times the carbon emissions of fossil diesel.

- Abrahm Lustgarten (20 November 2018). "Supposed to Help Save the Planet. Instead It Unleashed a Catastrophe". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

six of the world’s leading carbon-modeling schemes, including the E.P.A.’s, have concluded that biodiesel made from Indonesian palm oil makes the global carbon problem worse, not better

- Choong, Meng Yew (27 March 2012). "Waste not the palm oil biomass". The Star Online. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- Loh Soh Kheang; Choo Yuen May; Cheng Sit Food; Ma Ah Ngan (18 June 2006). Recovery and conversion of palm olein-derived used frying oil to methyl esters for biodiesel (PDF). Journal of Palm Oil Research (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 July 2010. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- Antimicrobial effects of palm kernel oil and palm oil Archived 2 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine Ekwenye, U.N and Ijeomah, King Mongkut's Institute of Technology Ladkrabang Science Journal, Vol. 5, No. 2, Jan–Jun 2005

- "Global Palm Oil Market Overview – 2018 – IndexBox". www.indexbox.io. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- Prokurat, Sergiusz (2013). "Palm oil – strategic source of renewable energy in Indonesia and Malaysia" (PDF). Journal of Modern Science: 425–443. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- "Global production volume palm oil, 2012–2019 l Statistic".

- Scientific American Board of Editors (December 2012), "The Other Oil Problem", Scientific American, 307 (6), p. 10, doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1212-10,

...such as Indonesia, the world's largest producer of palm oil.

- Indonesia: Palm Oil Production Prospects Continue to Grow Archived 10 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine December 31, 2007, USDA-FAS, Office of Global Analysis

- "P&G may build oleochemical plant to secure future supply". The Jakarta Post. 24 May 2011. Archived from the original on 25 July 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- Morales, Alex (18 November 2010). "Malaysia Has Little Room for Expanding Palm-Oil Production, Minister Says". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 12 September 2012. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- Scott-Thomas, Caroline (17 September 2012). "French firms urged to back away from 'no palm oil' label claims". Foodnavigator. Archived from the original on 12 March 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- Pakiam, Ranjeetha (3 January 2013). "Palm Oil Advances as Malaysia's Export Tax May Boost Shipments". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- "MPOB expects CPO production to increase to 19 million tonnes this year". The Star Online. 15 January 2013. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- "Malaysia: Stagnating Palm Oil Yields Impede Growth". USDA Foreign Agricultural Service. 11 December 2012. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- May, Choo Yuen (September 2012). "Malaysia: economic transformation advances oil palm industry". American Oil Chemists' Society. Archived from the original on 13 November 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- "Subscribe to read". Financial Times. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- Ayodele, Thompson (August 2010). "African Case Study: Palm Oil and Economic Development in Nigeria and Ghana; Recommendations for the World Bank's 2010 Palm Oil Strategy" (PDF). Initiative For Public Policy Analysis. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 April 2012. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- Ayodele, Thompson (15 October 2010). "The World Bank's Palm Oil Mistake". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- Arunmas, Phusadee; Wipatayotin, Apinya (28 January 2018). "EU move fuelling unease among palm oil producers" (Spectrum). Bangkok Post. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- Fedepalma Annual Communication of Progress Archived 16 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, 2006

- Bacon, David (18 July 2007). "Blood on the Palms: Afro-Colombians fight new plantations". Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. See also "Unfulfilled Promises and Persistent Obstacles to the Realization of the Rights of Afro-Colombians," A Report on the Development of Ley 70 of 1993 by the Repoport Center for Human Rights and Justice, Univ. of Texas at Austin, Jul 2007.

- "Ecuador to invest $1.2bn in palm oil sustainability & innovation: 'There is a tremendous opportunity here'". Food Navigator. 4 May 2018.

- Pazos, Flavio (3 August 2007). "Benin: Large scale oil palm plantations for agrofuel". World Rainforest Movement. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014.

- African Biodiversity Network (2007). Agrofuels in Africa: the impacts on land, food and forests: case studies from Benin, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia. translated by. African Biodiversity Network. Archived from the original on 18 April 2016.

- Report Assails Palm Oil Project in Cameroon Archived 9 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine September 5, 2012 New York Times

- "Cameroon changes mind on Herakles palm oil project". World Wildlife Fund. 21 June 2013. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- "Hybrid oil palms bear fruit in western Kenya". UN FAO. 24 November 2003. Archived from the original on 22 January 2015.

- Budidarsono, Suseno; Dewi, Sonya; Sofiyuddin, Muhammad; Rahmanulloh, Arif. "Socio-Economic Impact Assessment of Palm Oil Production" (PDF). World Agroforestry Centre. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 January 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Norwana, Awang Ali Bema Dayang; Kunjappan, Rejani (2011). "The local impacts of oil palm expansion in Malaysia" (PDF). cifor.org. Center for International Forestry Research. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 June 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Ismail, Saidi Isham (9 November 2012). "Palm oil transforms economic landscape". Business Times. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- "Palm oil cultivation for biofuel blocks return of displaced people in Colombia" (PDF) (Press release). Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. 5 November 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2007. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Colchester, Marcus; Jalong, Thomas; Meng Chuo, Wong (2 October 2012). "Free, Prior and Informed Consent in the Palm Oil Sector – Sarawak: IOI-Pelita and the community of Long Teran Kanan". Forest Peoples Program. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ""Losing Ground" – report on indigenous communities and oil palm development from LifeMosaic, Sawit Watch and Friends of the Earth". Forest Peoples Programme. 28 February 2008. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Indonesian migrant workers: with particular reference in the oil palm plantation industries in Sabah, Malaysia. Biomass Society (Report). Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University. 11 December 2010. Archived from the original on 11 January 2014.

- "Malaysia Plans High-Tech Card for Foreign Workers". ABC News. 9 January 2014. Archived from the original on 13 January 2014.

- "Malaysia rounds up thousands of migrant workers". BBC News. 2 September 2013. Archived from the original on 5 September 2013.

- hybrid oil palm project in Western Kenya Archived 22 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine FAO

- Ibrahim, Ahmad (31 December 2012). "Felcra a success story in rural transformation". New Straits Times. Archived from the original on 13 April 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- Man Kee Kam; Kok Tat Tan; Keat Teong Lee; Abdul Rahman Mohamed (9 September 2008). Malaysian Palm oil: Surviving the food versus fuel dispute for a sustainable future. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews (Report). Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- Corley, R. H. V. (2009). "How much palm oil do we need?". Environmental Science & Policy. 12 (2): 134–838. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2008.10.011.

- Spinks, Rosie J (17 December 2014). "Why does palm oil still dominate the supermarket shelves?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 December 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- "Oil palms need one-ninth of land used by other vegetable oil crops". Jakarta Post. 6 February 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- Atabani, A. E.; Silitonga, A. S.; Badruddin, I. A.; Mahlia, T. M. I.; Masjuki, H. H.; Mekhilef, S. (2012). "A comprehensive review on biodiesel as an alternative energy resource and its characteristics". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 16 (4): 2070–2093. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2012.01.003.

- Laura Paddison (29 September 2017). "From algae to yeast: the quest to find an alternative to palm oil". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- Clay, Jason (2004). World Agriculture and the Environment. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-55963-370-3.

- "Palm oil: Cooking the Climate". Greenpeace. 8 November 2007. Archived from the original on 10 April 2010. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- "The bird communities of oil palm and rubber plantations in Thailand" (PDF). The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- Foster, Joanna M. (1 May 2012). "A Grim Portrait of Palm Oil Emissions". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Yui, Sahoko; Yeh, Sonia (1 December 2013). "Land use change emissions from oil palm expansion in Pará, Brazil depend on proper policy enforcement on deforested lands". Environmental Research Letters. 8 (4): 044031. Bibcode:2013ERL.....8d4031Y. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/8/4/044031. ISSN 1748-9326.

- "Palm oil threatening endangered species" (PDF). Center for Science in the Public Interest. May 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 September 2012.

- "Camera catches bulldozer destroying Sumatra tiger forest". World Wildlife Fund. 12 October 2010. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Fargione, Joseph; Hill, Jason; Tilman, David; Polasky, Stephen; Hawthorne, Peter (7 February 2008). "Land Clearing and the Biofuel Carbon Debt". Science. 319 (5867): 1235–1238. Bibcode:2008Sci...319.1235F. doi:10.1126/science.1152747. PMID 18258862. Archived from the original on 28 May 2011.

- Meijaard, E; et al. (2018). Oil palm and biodiversity. A situation analysis by the IUCN Oil Palm Task Force (PDF) (PDF ed.). Gland: IUCN Oil Palm Task Force. ISBN 978-2-8317-1910-8. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- "Snack food giants fall short on palm oil deforestation promises". Food and Drink International. 17 January 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- "Biggest food brands 'failing goals to banish palm oil deforestation'". The Guardian. 17 January 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- "Palm Oil Buyers' Scorecard Analysis". WWF. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- "Oil World". Oil World. 18 January 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- New EU Food Labeling Rules Published (PDF). USDA Foreign Agricultural Service (Report). 12 January 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 April 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- "Deforestation: Mobilising resources to help achieve zero net deforestation by 2020". Consumer Goods Forum. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- Browne, Pete (6 November 2009). "Defining 'Sustainable' Palm Oil Production". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- Gunasegaran, P. (8 October 2011). "The beginning of the end for RSPO?". The Star Online. Archived from the original on 13 April 2013. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- Yulisman, Linda (4 June 2011). "RSPO trademark, not much gain for growers: Gapki". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- "What is Green Palm?". Green Palm. Archived from the original on 3 October 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- Watson, Elaine (5 October 2012). "WWF: Industry should buy into GreenPalm today, or it will struggle to source fully traceable sustainable palm oil tomorrow". Foodnavigator. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- "Growing pressure for stricter palm oil standards. Agritrade 19 Jan 2014". Archived from the original on 24 February 2014.

- Diet Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases (PDF). World Health Organization (Report). 2003. p. 82,88. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- "The other oil spill". The Economist. 24 June 2010. Archived from the original on 9 February 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- Bradsher, Keith (19 January 2008). "A New, Global Oil Quandary: Costly Fuel Means Costly Calories". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 January 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- Mancini, A; Imperlini, E; Nigro, E; Montagnese, C; Daniele, A; Orrù, S; Buono, P (2015). "Biological and Nutritional Properties of Palm Oil and Palmitic Acid: Effects on Health". Molecules. 20 (9): 17339–61. doi:10.3390/molecules200917339. PMC 6331788. PMID 26393565.

- Sacks FM, Lichtenstein AH, Wu JH, Appel LJ, Creager MA, Kris-Etherton PM, Miller M, Rimm EB, Rudel LL, Robinson JG, Stone NJ, Van Horn LV (2017). "Dietary Fats and Cardiovascular Disease: A Presidential Advisory from the American Heart Association". Circulation. 136 (3): e1–e23. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000510. PMID 28620111.

- Mozaffarian, D; Clarke, R (2009). "Quantitative effects on cardiovascular risk factors and coronary heart disease risk of replacing partially hydrogenated vegetable oils with other fats and oils" (PDF). European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 63 Suppl 2: S22–33. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602976. PMID 19424216.

- Sun, Ye; Neelakantan, Nithya; Wu, Yi; Lote-Oke, Rashmi; Pan, An; van Dam, Rob M (20 May 2015). "Palm Oil Consumption Increases LDL Cholesterol Compared with Vegetable Oils Low in Saturated Fat in a Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials". The Journal of Nutrition. 145 (7): 1549–1558. doi:10.3945/jn.115.210575. ISSN 0022-3166. PMID 25995283.

- "The skinny on fats". American Heart Association. 30 April 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- Brown, Ellie; Jacobson, Michael F. (2005). Cruel Oil: How Palm Oil Harms Health, Rainforest & Wildlife (PDF). Center for Science in the Public Interest. Washington, D.C. pp. iv, 3–5. OCLC 224985333. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 March 2009.

- Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases, WHO Technical Report Series 916, Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation, World Health Organization, Geneva, 2003, p. 88 (Table 10)