Free-rider problem

In economics, the free-rider problem occurs when those who benefit from resources, public goods, or services do not pay for them, which results in an underprovision of those goods or services.[1] For example, a free-rider may frequently ask for available parking lots (public goods) from those who have already paid for them, in order to benefit from free parking. That is, the free-rider may use the parking even more than the others without paying a penny. The free-rider problem is the question of how to limit free riding and its negative effects in these situations. The free-rider problem may occur when property rights are not clearly defined and imposed.[2]

The free-rider problem is common with goods which are non-excludable, including public goods and situations of the Tragedy of the Commons.

Although the term "free rider" was first used in economic theory of public goods, similar concepts have been applied to other contexts, including collective bargaining, antitrust law, psychology and political science.[3] For example, some individuals in a team or community may reduce their contributions or performance if they believe that one or more other members of the group may free ride.[4]

The economic problem with free riding

Free riding is a problem of economic inefficiency when it leads to the under-production or over-consumption of a good. For example, when people are asked how much they value a particular public good, with that value measured in terms of how much money they would be willing to pay, their tendency is to under report their valuations.[5]

Goods which are subject to free riding are usually characterized by the inability to exclude nonpayers. This problem is sometimes compounded by the fact that common-property goods are characterized by rival consumption. Not only can consumers of common-property goods benefit without payment, but consumption by one imposes an opportunity cost on others. This will lead to overconsumption and even possibly exhaustion or destruction of the common-property good. If too many people start to free ride, a system or service will eventually not have enough resources to operate.

The other problem of free-riding is experienced when the production of goods does not consider the external costs, particularly the use of ecosystem services.

Economic and political solutions

Assurance contracts

An assurance contract is a contract in which participants make a binding pledge to contribute to building a public good, contingent on a quorum of a predetermined size being reached. Otherwise the good is not provided and any monetary contributions are refunded.

A dominant assurance contract is a variation in which an entrepreneur creates the contract and refunds the initial pledge plus an additional sum of money if the quorum is not reached. (The entrepreneur profits by collecting a fee if the quorum is reached and the good is provided.) In game-theoretic terms this makes pledging to build the public good a dominant strategy: the best move is to pledge to the contract regardless of the actions of others. [6]

Coasian solution

A Coasian solution, named for the economist Ronald Coase, proposes that potential beneficiaries of a public good can negotiate to pool their resources and create it, based on each party's self-interested willingness to pay. His treatise, "The Problem of Social Cost" (1960), argued that if the transaction costs between potential beneficiaries of a public good are low—that it is easy for potential beneficiaries to find each other and organize a pooling their resources based upon the good's value to each of them—that public goods could be produced without government action.[7]

Much later, Coase himself wrote that while what had become known as the Coase Theorem had explored the implications of zero transaction costs, he had actually intended to use this construct as a stepping-stone to understand the real world of positive transaction costs, corporations, legal systems and government actions:[8][9]

I examined what would happen in a world in which transaction costs were assumed to be zero. My aim in doing so was not to describe what life would be like in such a world but to provide a simple setting in which to develop the analysis and, what was even more important, to make clear the fundamental role which transaction costs do, and should, play in the fashioning of the institutions which make up the economic system.

Coase also wrote:

The world of zero transaction costs has often been described as a Coasian world. Nothing could be further from the truth. It is the world of modern economic theory, one which I was hoping to persuade economists to leave. What I did in "The Problem of Social Cost" was simply to shed light on some of its properties. I argued in such a world the allocation of resources would be independent of the legal position, a result which Stigler dubbed the "Coase theorem".[10]

Thus, while Coase himself appears to have considered the "Coase theorem" and Coasian solutions as simplified constructs to ultimately consider the real 20th-century world of governments and laws and corporations, these concepts have become attached to a world where transaction costs were much lower, and government intervention would unquestionably be less necessary.

A minor alternative, especially for information goods, is for the producer to refuse to release a good to the public until payment to cover costs is met. Author Stephen King, for instance, authored chapters of a new novel downloadable for free on his website while stating that he would not release subsequent chapters unless a certain amount of money was raised. Sometimes dubbed holding for ransom, this method of public goods production is a modern application of the street performer protocol for public goods production. Unlike assurance contracts, its success relies largely on social norms to ensure (to some extent) that the threshold is reached and partial contributions are not wasted.

One of the purest Coasian solutions today is the new phenomenon of Internet crowdfunding. Here rules are enforced by computer algorithms and legal contracts as well as social pressure. For example, on the Kickstarter site, each funder authorizes a credit card purchase to buy a new product or receive other promised benefits, but no money changes hands until the funding goal is met.[11] Because automation and the Internet so reduce the transaction costs for pooling resources, project goals of only a few hundred dollars are frequently crowdfunded, far below the costs of soliciting traditional investors.

Government provision

If voluntary provision of public goods will not work, then the solution is making their provision involuntary. This saves each of us from our own tendency to be a free rider, while also assuring us that no one else will be allowed to free ride. One frequently proposed solution to the problem is for governments or states to impose taxation to fund the production of public goods. This does not actually solve the theoretical problem because good government is itself a public good. Thus it is difficult to ensure the government has an incentive to provide the optimum amount even if it were possible for the government to determine precisely what amount would be optimum. These issues are studied by public choice theory and public finance.

Sometimes the government provides public goods using "unfunded mandates". An example is the requirement that every car be fit with a catalytic converter. This may be executed in the private sector, but the end result is predetermined by the state: the individually involuntary provision of the public good clean air. Unfunded mandates have also been imposed by the U.S. federal government on the state and local governments, as with the Americans with Disabilities Act, for example.

Regardless the role of the government is provide vital goods to all individuals, some of which they cannot obtain on themselves.[12] In order to ensure that government services are properly funded taxes and other government controlled entities are enforced.[13] Although enforced taxes deter the free-rider problem many contend that some goods should be excluded and made into private goods. However, this not possible with all goods such as pure public goods that are inseparable and inclusive, thus require "provision by public means".[14] In short, the government has a responsibility to ensure that the social welfare of individuals is met as opposed to privatized goods.[15]

Subsidies and joint products

A government may subsidize production of a public good in the private sector. Unlike government provision, subsidies may result in some form of a competitive market. The potential for cronyism (for example, an alliance between political insiders and the businesses receiving subsidies) can be limited with secret bidding for the subsidies or application of the subsidies following clear general principles. Depending on the nature of a public good and a related subsidy, principal–agent problems can arise between the citizens and the government or between the government and the subsidized producers; this effect and counter-measures taken to address it can diminish the benefits of the subsidy.

Subsidies can also be used in areas with a potential for non-individualism: For instance, a state may subsidize devices to reduce air pollution and appeal to citizens to cover the remaining costs.

Similarly, a joint-product model analyzes the collaborative effect of joining a private good to a public good. For example, a tax deduction (private good) can be tied to a donation to a charity (public good). It can be shown that the provision of the public good increases when tied to the private good, as long as the private good is provided by a monopoly (otherwise the private good would be provided by competitors without the link to the public good).

Privileged group

The study of collective action shows that public goods are still produced when one individual benefits more from the public good than it costs him to produce it; examples include benefits from individual use, intrinsic motivation to produce, and business models based on selling complement goods. A group that contains such individuals is called a privileged group. A historical example could be a downtown entrepreneur who erects a street light in front of his shop to attract customers; even though there are positive external benefits to neighboring nonpaying businesses, the added customers to the paying shop provide enough revenue to cover the costs of the street light.

The existence of privileged groups may not be a complete solution to the free rider problem, however, as underproduction of the public good may still result. The street light builder, for instance, would not consider the added benefit to neighboring businesses when determining whether to erect his street light, making it possible that the street light isn't built when the cost of building is too high for the single entrepreneur even when the total benefit to all the businesses combined exceeds the cost.

An example of the privileged group solution could be the Linux community, assuming that users derive more benefit from contributing than it costs them to do it. For more discussion on this topic see also Coase's Penguin.

Another example is those musicians and writers who create music and writings for their own personal enjoyment, and publish because they enjoy having an audience. Financial incentives are not necessary to ensure the creation of these public goods. Whether this creates the correct production level of writings and music is an open question.

Merging free riders

Another method of overcoming the free rider problem is to simply eliminate the profit incentive for free riding by buying out all the potential free riders. A property developer that owned an entire city street, for instance, would not need to worry about free riders when erecting street lights since he owns every business that could benefit from the street light without paying. Implicitly, then, the property developer would erect street lights until the marginal social benefit met the marginal social cost. In this case, they are equivalent to the private marginal benefits and costs.

While the purchase of all potential free riders may solve the problem of underproduction due to free riders in smaller markets, it may simultaneously introduce the problem of underproduction due to monopoly. Additionally, some markets are simply too large to make a buyout of all beneficiaries feasible—this is particularly visible with public goods that affect everyone in a country.

Introducing an exclusion mechanism (club goods)

Another solution, which has evolved for information goods, is to introduce exclusion mechanisms which turn public goods into club goods. One well-known example is copyright and patent laws. These laws, which in the 20th century came to be called intellectual property laws, attempt to remove the natural non-excludability by prohibiting reproduction of the good. Although they can address the free rider problem, the downside of these laws is that they imply private monopoly power and thus are not Pareto-optimal.

For example, in the United States, the patent rights given to pharmaceutical companies encourage them to charge high prices (above marginal cost)[16] and to advertise to convince patients to persuade their doctors to prescribe the drugs. Likewise, copyright provides an incentive for a publisher to act like The Dog in the Manger, taking older works out of print so as not to cannibalize revenue from the publisher's own new works.[17]

The laws also end up encouraging patent and copyright owners to sue even mild imitators in court and to lobby for the extension of the term of the exclusive rights in a form of rent seeking.

These problems with the club-good mechanism arise because the underlying marginal cost of giving the good to more people is low or zero, but, because of the limits of price discrimination those who are unwilling or unable to pay a profit-maximizing price do not gain access to the good.

If the costs of the exclusion mechanism are not higher than the gain from the collaboration, club goods can emerge naturally. James M. Buchanan showed in his seminal paper that clubs can be an efficient alternative to government interventions.[18]

On the other hand, the inefficiencies and inequities of club goods exclusions sometimes cause potentially excludable club goods to be treated as public goods, and their production financed by some other mechanism. Examples of such "natural" club goods include natural monopolies with very high fixed costs, private golf courses, cinemas, cable television and social clubs. This explains why many such goods are often provided or subsidized by governments, co-operatives or volunteer associations, rather than being left to be supplied by profit-minded entrepreneurs. These goods are often known as social goods.

Joseph Schumpeter claimed that the "excess profits", or profits over normal profit, generated by the copyright or patent monopoly will attract competitors that will make technological innovations and thereby end the monopoly. This is a continual process referred to as "Schumpeterian creative destruction", and its applicability to different types of public goods is a source of some controversy. The supporters of the theory point to the case of Microsoft, for example, which has been increasing its prices (or lowering its products' quality), predicting that these practices will make increased market shares for Linux and Apple largely inevitable.

A nation can be seen as a club whose members are its citizens. Government would then be the manager of this club. This is further studied in the Theory of the State.

Altruistic solutions

Social norms

When enough people do not think like free-riders, the private and voluntary provision of public goods may be successful. For example, a free rider might come to a public park to enjoy its beauty, yet discard litter that makes it less enjoyable for others. Other public-spirited individuals don't do this and might even pick up existing litter. Reasons for the act could be that the person derives pleasure from helping their community, feels ashamed if their neighbors or friends saw them, or could be emotionally attached to the public good. People unconsciously adapt their behavior to that of their peers; this is conformity. Even people who engaged in free-riding by littering elsewhere are less likely to if they see others hold on to their trash.

Social norms can be observed wherever people interact, not only in physical spaces but in virtual communities on the Internet. For example, if a disabled person boards a crowded bus, everyone expects that some able-bodied person will volunteer their seat. The same social norm, although executed in a different environment, can also be applied to the Internet. If a user enters a discussion in a chat room and continues to use all capital letters or to make personal attacks ("flames") when addressing other users, the culprit may realize he or she has been blocked by other participants. As in real life, users learning to adapt to the social norms of cyberspace communities provide a public good—here, not suffering disruptive online behavior—for all the participants.

Social sanctions (punishment)

Experimental literature suggests that free riding can be overcome without any state intervention. Peer-to-peer punishment, that is, members sanction those members that do not contribute to the public good at a cost, is sufficient to establish and maintain cooperation.[19][20] Such punishment is often considered altruistic, because it comes at a cost to the punisher, however, the exact nature remains to be explored.[21] Whether costly punishment can explain cooperation is disputed.[22] Recent research finds that costly punishment is less effective in real world environments. For example, punishment works relatively badly under imperfect information, where people cannot observe the behavior of others perfectly.[23]

Voluntary organizations

Organizations such as the Red Cross, public radio and television or a volunteer fire department provide public goods to the majority at the expense of a minority who voluntarily participate or contribute funds. Contributions to online collaborative media like Wikipedia and other wiki projects, and free software projects such as Linux are another example of relatively few contributors providing a public good (information) freely to all readers or software users.

Proposed explanations for altruistic behavior include biological altruism and reciprocal altruism. For example, voluntary groups such as labor unions and charities often have a federated structure, probably in part because voluntary collaboration emerges more readily in smaller social groups than in large ones (e.g., see Dunbar's number).

While both biological and reciprocal altruism are observed in other animals, our species' complex social behaviors take these raw materials much farther. Philanthropy by wealthy individuals—some, such as Andrew Carnegie giving away their entire vast fortunes—have historically provided a multitude of public goods for others. One major impact was the Rockefeller Foundation's development of the "Green Revolution" hybrid grains that probably saved many millions of people from starvation in the 1970s. Christian missionaries, who typically spend large parts of their lives in remote, often dangerous places, have had disproportionate impact compared with their numbers worldwide for centuries. Communist revolutionaries in the 20th century had similar dedication and outsized impacts. International relief organizations such as Doctors Without Borders, Save the Children and Amnesty International have benefited millions, while also occasionally costing workers their lives. For better and for worse, humans can conceive of, and sacrifice for, an almost infinite variety of causes in addition to their biological kin.

Religions and ideologies

Voluntary altruistic organizations often motivate their members by encouraging deep-seated personal beliefs, whether religious or other (such as social justice or environmentalism) that are taken "on faith" more than proved by rational argument. When individuals resist temptations to free riding (e.g., stealing) because they hold these beliefs (or because they fear the disapproval of others who do), they provide others with public goods that might be difficult or impossible to "produce" by administrative coercion alone.

One proposed explanation for the ubiquity of religious belief in human societies is multi-level selection: altruists often lose out within groups, but groups with more altruists win. A group whose members believe a "practical reality" that motivates altruistic behavior may out-compete other groups whose members' perception of "factual reality" causes them to behave selfishly. A classic example is a soldier's willingness to fight for his tribe or country. Another example given in evolutionary biologist David Sloan Wilson's Darwin's Cathedral is the early Christian church under the late Roman Empire; because Roman society was highly individualistic, during frequent epidemics many of the sick died not of the diseases per se but for lack of basic nursing. Christians, who believed in an afterlife, were willing to nurse the sick despite the risks. Although the death rate among the nurses was high, the average Christian had a much better chance of surviving an epidemic than other Romans did, and the community prospered.

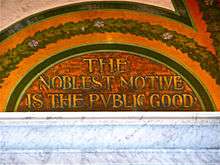

Religious and non-religious traditions and ideologies (such as nationalism and patriotism) are in full view when a society is in crisis and public goods such as defense are most needed. Wartime leaders invoke their God's protection and claim that their society's most hallowed traditions are at stake. For example, according to President Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address during the American Civil War, the Union was fighting so "that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth". Such voluntary, if exaggerated, exhortations complement forcible measures—taxation and conscription—to motivate people to make sacrifices for their cause.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Baumol, William (1952). Welfare Economics and the Theory of the State. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Pasour, Jr., E. C. "The Free Rider as a Basis for Government Intervention" (PDF). Libertarian Studies. Retrieved 2014-10-25.

- ↑ Hendriks, Carolyn M. (December 2006). "When the Forum Meets Interest Politics: Strategic Uses of Public Deliberation". Politics & Society (Vol. 34-4). doi:10.1177/0032329206293641.

- ↑ Ruël, Gwenny Ch.; Bastiaans, Nienke and Nauta, Aukje. "Free-riding and team performance in project education"

- ↑ Goodstein, Eban (2014). Economics and the Environment (7 ed.). University of Minnesota: Library of Congress. ISBN 978-1-118-53972-9.

- ↑ "{title}" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 January 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- ↑ Coase, Ronald (October 1960). "The Problem of Social Cost". Journal of Law and Economics. 3: 1–44. doi:10.1086/466560.

- ↑ Fox, Glenn. "The Real Coase Theorems" (PDF). Cato Journal 27, Fall 2007. Cato Institute, Washington, D.C. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ↑ Coase, Ronald (1988). The Firm, the Market and the Law. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. p. 13.

- ↑ Coase, Ronald (1988). The Firm, the Market and the Law. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. p. 174.

- ↑ "Kickstarter FAQ". Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ↑ Thompson, Donald. "The Proper Role of Government: Considering Public Goods and Private Goods". The Pennsylvania State University, 2015

- ↑ Jakacky, Gary. "The Role of Government in Providing". Newsmax Finance, 2016

- ↑ Jackson, Bill. "Public Goods and Services". The Social Studies Help Center, 2016

- ↑ Holtz, Brian. "The Proper Role of Government". Holtz for Congress, 2016

- ↑ https://www.quora.com/Do-patents-increase-the-price-of-drugs

- ↑ Examples from the entertainment industry include Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment's "vault" sales practice and its outright refusal to issue Song of the South on home video in most markets. Examples from the computer software industry include Microsoft's decision to pull Windows XP from the market in mid-2008 to drive revenue from the widely criticized Windows Vista operating system.

- ↑ James M. Buchanan (February 1965). "An Economic Theory of Clubs". Economica. 32 (125): 1–14. doi:10.2307/2552442. JSTOR 2552442.

- ↑ Elinor Ostrom; James Walker; Roy Gardner (June 1992). "Covenants With and without a Sword: Self-Governance Is Possible". American Political Science Review. 86 (2): 404–17. doi:10.2307/1964229. JSTOR 1964229.

- ↑ Fehr, E., & S. Gächter (2000) "Cooperation and Punishment in Public Goods Experiments", 90 American Economic Review 980.

- ↑ Fehr, Ernst; Gächter, Simon (2002). "Altruistic punishment in humans". Nature. 415 (6868): 137–40. doi:10.1038/415137a. PMID 11805825.

- ↑ Dreber, Anna; et al. (2008). "Winners don't punish". Nature. 452 (7185): 348–51. doi:10.1038/nature06723. PMC 2292414. PMID 18354481.

- ↑ Kristoffel Grechenig, Nicklisch; Thöni, C. (2010). "Punishment despite reasonable doubt – a public goods experiment with sanctions under uncertainty". Journal of Empirical Legal Studies. 7 (4): 847–67. doi:10.1111/j.1740-1461.2010.01197.x. SSRN 1586775.

Further reading

- Cornes, Richard; Sandler, Todd (1986). The Theory of Externalities, Public Goods and Club Goods. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 052130184X.

- William D. Nordhaus, "A New Solution: the Climate Club" (a review of Gernot Wagner and Martin L. Weitzman, Climate Shock: The Economic Consequences of a Hotter Planet, Princeton University Press, 250 pp, $27.95), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXII, no. 10 (June 4, 2015), pp. 36–39.

- Venugopal, Joshi (2005). "Drug imports: the free-rider paradox". Express Pharma Pulse. 11 (9): 8.

- P. Oliver – Sociology 626 published by Social Science Computing Cooperative University of Wisconsin