Ureparapara

Coordinates: 13°32′S 167°20′E / 13.533°S 167.333°E

| Native name: Noypēypay, Aö | |

|---|---|

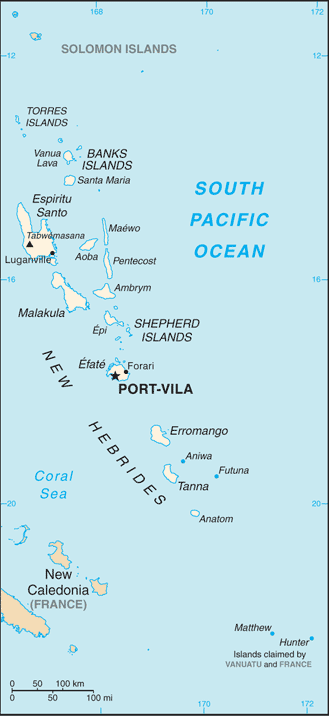

Ureparapara, in the Banks Islands | |

| |

| Geography | |

| Location | Pacific Ocean |

| Archipelago | Vanuatu, Torres Islands |

| Area | 39 km2 (15 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 300 m (1,000 ft) |

| Highest point | Mt Qusetowqas |

| Administration | |

| Province | Torba Province |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 437 (2009) |

Ureparapara (also known as Parapara for short; once known as Bligh Island) is the third largest island in the Banks group of northern Vanuatu, after Gaua and Vanua Lava.

History

The first recorded European who arrived to Ureparapara was the Spanish explorer Pedro Fernández de Quirós on 15 June 1606. He first named the island Pilar de Zaragoza; however, later on, it is charted as Nuestra Señora de Montserrate both by him and his chaplain Fray Martin de Munilla.[1]

In 1789, the island was rediscovered by William Bligh, during his journey from Tonga to Timor after the mutiny on the Bounty.[2] After this, Ureparapara was known for a while under the name Bligh Island.[3][4]

Geography

Ureparapara island is an old volcanic cone that has been breached by the sea on its east coast, forming Divers Bay. Apart from this indentation, the island is circular in shape, with a diameter of fifteen kilometres (9.3 miles). The land area is 39 square kilometres (15 square miles).

Population

The population was 437 in 2009.[5] There are three villages on the island. The main village is Léar (Leserepla).[6] The others are Lehali (on the west coast) and Leqyangle.[7]

Two languages are traditionally spoken on the island, Löyöp and Lehali.[8]

Name

The name Ureparapara reflects the way the island is named in the language of Mota, which was once chosen by missionaries, at the end of the 19th century, as the reference language for the area.

The island is locally named Noypēypay [nɔjpejˈpaj] in Lehali, and Aö [aˈø] in Löyöp

Historical sites

Ureparapara is known to host historical sites made of coral stone, named nowon and votwos in Lehali. These ancestral villages, located inland in the forest, were abandoned in the 19th century, yet have been preserved under the vegetation; they have been proposed for inclusion amongst the World Heritage sites of UNESCO.[9] One of the most famous sites is a 12-feet high stone platform called Votwos. These used to serve as a ceremonial platform for the high-profile grade-taking ceremonies, known as sok or nsok in Lehali, and referred to in the anthropological literature as suqe or sukwe (after their name in Mota).[10]

These sites are now only visited for ceremonial purposes, as most people nowadays live along the coast.

References

- ↑ Kelly, Celsus, O.F.M. La Austrialia del Espiritu Santo. The Journal of Fray Martín de Munilla O.F.M. and other documents relating to the Voyage of Pedro Fernández de Quirós to the South Sea (1605-1606) and the Franciscan Missionary Plan (1617-1627) Cambridge, 1966, p.121.

- ↑ See A chart of islands to the north of the New Hebrides discovered by Captain William Bligh.

- ↑ See p.162 of Ida Lee. 1920. Captain Bligh’s second voyage to the South Sea. Longmans, Green.

- ↑ See for example The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, 1834.

- ↑ "2009 National Census of Population and Housing: Summary Release" (PDF). Vanuatu National Statistics Office. 2009. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ↑ Vincent Lebot und Pierre Cabalion: Les Kavas de Vanuatu, S. 83

- ↑ Maffi & Taylor, 1977, "The Mosquitoes Of The Banks And Torres Island Groups Of The South Pacific".

- ↑ François (2012); see also Detailed list and map of the Banks and Torres languages.

- ↑ "The Nowon and Votwos of Ureparapara", Tentative list for UNESCO World Heritage sites (homepage of UNESCO).

- ↑ François (2013), p.234.

Bibliography

- François, Alexandre (2012), "The dynamics of linguistic diversity: Egalitarian multilingualism and power imbalance among northern Vanuatu languages", International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 214: 85–110, doi:10.1515/ijsl-2012-0022 .

- François, Alexandre (2013), "Shadows of bygone lives: The histories of spiritual words in northern Vanuatu", in Mailhammer, Robert, Lexical and structural etymology: Beyond word histories, Studies in Language Change, 11, Berlin: DeGruyter Mouton, pp. 185–244, ISBN 978-1-61451-058-1 .