United States presidential elections in which the winner lost the popular vote

There have been five United States presidential elections in which the winner lost the popular vote including the 1824 election, which was the first U.S. presidential election where the popular vote was recorded.[1] Losing the popular vote means securing less of the national popular vote than the person who received either a majority or a plurality of the vote.[2][3]

In the U.S. presidential election system, instead of the nationwide popular vote determining the outcome of the election, the President of the United States is determined by votes cast by electors of the Electoral College. Alternatively, if no candidate receives an absolute majority of electoral votes, the election is determined by the House of Representatives. These procedures are governed by the Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

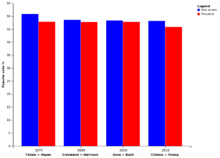

When individuals cast ballots in the general election, they are choosing electors and telling them whom they should vote for in the Electoral College. The "national popular vote" is the sum of all the votes cast in the general election, nationwide. The presidential elections of 1876, 1888, 2000, and 2016 produced an Electoral College winner who did not receive the most votes in the general election.[4][5][6] In 1824, there were six states in which electors were legislatively appointed, rather than popularly elected, so the true national popular vote is uncertain. When no candidate received a majority of electoral votes in 1824, the election was decided by the House of Representatives. For these two reasons, the 1824 election is distinguishable from the latter four elections, which were held after all states had instituted the popular selection of electors, and in each of which a single candidate won an outright majority of electoral votes, thus becoming president without a contingent election in the House of Representatives.[7] The true national popular vote total was also uncertain in the 1960 election, and the plurality winner depends on how votes for Alabama electors are allocated.[8]

Elections

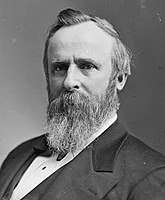

1824: John Quincy Adams

The 1824 presidential election was the first election in American history in which the popular vote mattered, as 18 states chose presidential electors by popular vote in 1824 (six states still left the choice up to their state legislatures). When the final votes were tallied in those 18 states, Andrew Jackson polled 152,901 popular votes to John Quincy Adams's 114,023; Henry Clay won 47,217, and William H. Crawford won 46,979. The electoral college returns, however, gave Jackson only 99 votes, 32 fewer than he needed for a majority of the total votes cast. Adams won 84 electoral votes followed by 41 for Crawford, and 37 for Clay.[9] All four candidates in the election identified with the Democratic-Republican Party.

As no candidate secured the required number of votes (131 total) from the Electoral College, the election was decided by the House of Representatives under the provisions of the Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Only the top three candidates in the electoral vote were admitted as candidates in this contingent election. Henry Clay, as the candidate with the fewest electoral votes, was eliminated from the deliberation. As Speaker of the House, however, Clay was still the most important player in determining the outcome of the election. The election was held on February 9, 1825, with each state having one vote, as determined by the wishes of the majority of each state's congressional representatives. Adams narrowly emerged as the winner, with majorities of the Representatives from 13 out of 25 states voting in his favor. Most of Clay's supporters, joined by several old Federalists, switched their votes to Adams in enough states to give him the election. Soon after his inauguration as President, Adams appointed Henry Clay as his secretary of state.[9] This result became a source of great bitterness for Jackson and his supporters, who proclaimed the election of Adams a "corrupt bargain," and were inspired to create the Democratic Party.[10][11]

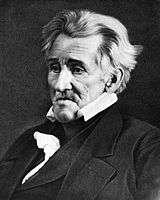

1876: Rutherford B. Hayes

The 1876 presidential election was one of the most contentious and controversial presidential elections in American history. The result of the election remains among the most disputed ever, although there is no question that Democrat Samuel J. Tilden of New York outpolled Ohio's Republican Rutherford B. Hayes in the popular vote, with Tilden winning 4,288,546 votes and Hayes winning 4,034,311. Tilden was, and remains, the only candidate in American history who lost a presidential election despite receiving a majority (not just a plurality) of the popular vote.[12]

After a first count of votes, Tilden won 184 electoral votes to Hayes' 165, with 20 votes unresolved. These 20 electoral votes were in dispute in four states: in the case of Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina, each party reported its candidate had won the state, while in Oregon one elector was declared illegal (as an "elected or appointed official") and replaced. The question of who should have been awarded these electoral votes is at the heart of the ongoing debate about the election of 1876.

An informal deal was struck to resolve the dispute: the Compromise of 1877, which awarded all 20 electoral votes to Hayes. In return for the Democrats' acquiescence in Hayes' election, the Republicans agreed to withdraw federal troops from the South, ending Reconstruction. The Compromise effectively ceded power in the Southern states to the Democratic Redeemers, who went on to pursue their agenda of returning the South to a political economy resembling that of its pre-war condition, including the disenfranchisement of black voters.[13][14]

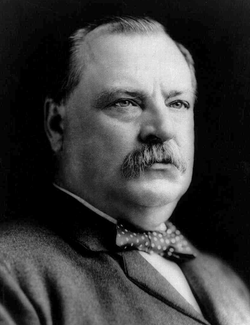

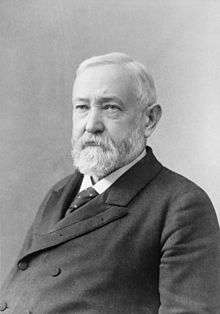

1888: Benjamin Harrison

In the 1888 election, Grover Cleveland of New York, the incumbent president and a Democrat, tried to secure a second term against the Republican nominee Benjamin Harrison, a former U.S. Senator from Indiana. The economy was prosperous and the nation was at peace, but although Cleveland received 90,596 more votes than Harrison, he lost in the Electoral College. Harrison won 233 electoral votes, Cleveland only 168.

Tariff policy was the principal issue in the election. Harrison took the side of industrialists and factory workers who wanted to keep tariffs high, while Cleveland strenuously denounced high tariffs as unfair to consumers. His opposition to Civil War pensions and inflated currency also made enemies among veterans and farmers. On the other hand, he held a strong hand in the South and border states, and appealed to former Republican Mugwumps.

Harrison swept almost the entire North and Midwest (losing only Connecticut and New Jersey), and narrowly carried the swing states of New York and Indiana (Harrison's home state) by a margin of 1% or less to achieve a majority of the electoral vote. Unlike the election of 1884, the power of the Tammany Hall political machine in New York City helped deny Cleveland the electoral votes of his home state.[15][16]

2000: George W. Bush

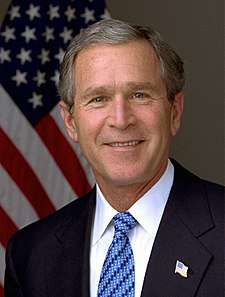

The 2000 presidential election pitted Republican candidate George W. Bush (the incumbent governor of Texas and son of former president George H. W. Bush) against Democratic candidate Al Gore (the incumbent Vice President of the United States under Bill Clinton). Despite Gore receiving 543,895 more votes (0.51% of all votes cast), the Electoral College chose Bush as president by a vote of 271 to 266.[17]

Vice President Gore secured the Democratic nomination with relative ease. Bush was seen as the early favorite for the Republican nomination, and despite a contentious primary battle with Senator John McCain and other candidates, secured the nomination by Super Tuesday. Many third-party candidates also ran, most prominently Ralph Nader. Bush chose former Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney as his running mate, and Gore chose Senator Joe Lieberman as his. Both major-party candidates focused primarily on domestic issues, such as the budget, tax relief, and reforms for federal social-insurance programs, though foreign policy was not ignored.[18]

The result of the election hinged on voting in Florida, where Bush's narrow margin of victory of just 537 votes out of almost 6 million votes cast on election night triggered a mandatory recount. Litigation in select counties started additional recounts, and this litigation ultimately reached the United States Supreme Court. The Court's contentious decision in Bush v. Gore, announced on December 12, 2000, ended the recounts, effectively awarding Florida's votes to Bush and granting him the victory. Later studies have reached conflicting opinions on who would have won the recount had it been allowed to proceed.[19] Nationwide, George Bush received 50,456,002 votes (47.87%) and Gore received 50,999,897 (48.38%).[17]

2016: Donald Trump

The 2016 presidential election featured Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton (former U.S. Senator from New York, Secretary of State, and First Lady to President Bill Clinton) and Republican nominee Donald Trump, a businessman (owner of the Trump Organization[20][21]) from New York City, who had no prior political experience or service in the military. Both nominees had turbulent journeys in primary races,[22][23] and were seen unfavorably by the general public.[24] The election saw multiple third-party candidates,[25] and there were over a million write-in votes cast.[26]

During the 2016 election, "pre-election polls fueled high-profile predictions that Hillary Clinton's likelihood of winning the presidency was about 90 percent, with estimates ranging from 71 to over 99 percent."[27] National polls were generally accurate, showing a Clinton lead of about 3% in the national popular vote (she ultimately won the national popular vote by 2.1%).[27] State-level polls "showed a competitive, uncertain contest...but clearly under-estimated Trump's support in the Upper Midwest."[27] Trump exceeded expectations on Election Day by winning the traditionally Democratic Rust Belt states of Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin by narrow margins.[28] Clinton recorded large margins in large states such as California, Illinois and New York, winning California by a margin of nearly 4.3 million votes, while coming closer to winning, but still losing by a significant margin Texas, Arizona and Georgia than any Democratic nominee since the turn of the millennium.[29] Clinton also won the Democratic medium-sized states such as Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Washington with vast margins. Clinton managed to edge out Trump in Virginia, a swing state where her running mate Tim Kaine had served as Governor. Trump also won the traditional bellwether state of Florida along with the recent battleground state of North Carolina, further contributing to the electoral flip of the popular vote. Trump won by a large margin in Indiana, Missouri, Ohio and Tennessee.

When the Electoral College cast its votes on December 19, 2016,[30] Trump received 304 votes to Clinton's 227 with seven electors defecting to other choices, the most faithless electors (2 from Trump, 5 from Clinton) in any presidential election in over a hundred years. Clinton had nonetheless received almost three million more votes (65,853,516 to 62,984,825) in the general election than Trump, giving Clinton a popular vote lead of 2.1% over Trump.[29][31]

After the election, Trump "falsely claim(ed) that millions of unauthorized immigrants had robbed him of a popular vote majority, ..."[32][33] Trump repeated this in a meeting with members of Congress in 2017,[32] and in a speech in April 2018.[34]

Comparative table of elections

| Democratic-Republican · DR Democratic · D Republican · R | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Election | Winner and party | Electoral College | Popular vote[lower-alpha 1] | Runner-up and party | Turnout[lower-alpha 1] | ||||||||

| Votes | % | Votes | Margin | % | Margin | % | |||||||

| 1824 | John Quincy Adams | DR | 84/261 | 32.18% | 113,122 | −38,149 | 30.92% | −10.44% | Andrew Jackson | DR | 26.90% | ||

| 1876 | Rutherford B. Hayes | R | 185/369 | 50.14% | 4,034,311 | −254,235 | 47.92% | −3.02% | Samuel J. Tilden | D | 81.80% | ||

| 1888 | Benjamin Harrison | R | 233/401 | 58.10% | 5,443,892 | −90,596 | 47.80% | −0.79% | Grover Cleveland | D | 79.30% | ||

| 2000[17] | George W. Bush | R | 271/538 | 50.37% | 50,456,002 | −543,895 | 47.87% | −0.51% | Al Gore | D | 51.20% | ||

| 2016[31] | Donald Trump | R | 304/538 | 55.50% | 62,984,825 | −2,868,691 | 46.09% | −2.10% | Hillary Clinton | D | 56.30% | ||

1960 Alabama results ambiguity

In the 1960 United States presidential election, Democratic candidate John F. Kennedy defeated Republican candidate Richard Nixon. Kennedy is generally considered to have won the popular vote as well, by a narrow margin, but based on the unusual nature of the election in Alabama, political journalists John Fund and Sean Trende have argued that Nixon actually won the popular vote.[36][37][38]

Historian and Kennedy associate Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. wrote that, "It is impossible to determine what Kennedy's popular vote in Alabama was" and under one scenario "Nixon would have won the popular vote by 58,000".[39] A third major candidate in the 1960 election was Harry Flood Byrd, Sr. who won 15 electoral votes nationwide that year. According to political scientist Steven Schier, "If one divides the Alabama Democratic votes proportionately between the Kennedy and Byrd slates, Nixon ekes out a 50,000 vote popular plurality...."[40][41] Indeed, Congressional Quarterly calculated the popular vote in this manner at the time of the 1960 election.[36]

See also

- Contemporary issues and criticism of the Electoral College

- List of United States presidential elections by Electoral College margin

- List of United States presidential elections by popular vote margin

- List of United States presidential candidates by number of votes received

- National Popular Vote Interstate Compact

- United States' presidential plurality victories

Notes

References

- ↑ "1824 Presidential election goes to the House". History. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ↑ Streb, Matthew J. (2015-10-30). Rethinking American Electoral Democracy. Routledge. p. 172. ISBN 9781317519829. OCLC 928999469.

- ↑ Savage, David (November 11, 2016). "For the fourth time in American history, the president-elect lost the popular vote. Credit the electoral college". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- ↑ Edwards III, George C. (2011). Why the Electoral College is Bad for America (Second ed.). New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-16649-1.

- ↑ Chang, Alvin (November 9, 2016). "Trump will be the 4th president to win the Electoral College after getting fewer votes than his opponent". Vox. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- ↑ "2016 Presidential Election". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved November 26, 2016.

- ↑ "Electoral College Mischief, The Wall Street Journal, September 8, 2004". Opinionjournal.com. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- ↑ "Did JFK Lose the Popular Vote?". RealClearPolitics. October 22, 2012. Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- 1 2 "John Quincy Adams: Campaigns and Elections". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- ↑ "The Election of 1824 Was Decided in the House of Representatives: The Controversial Election was Denounced as 'The Corrupt Bargain'", Robert McNamara, About.com

- ↑ Stenberg, R. R. (1934). "Jackson, Buchanan, and the "Corrupt Bargain" Calumny". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 58 (1): 61–85. doi:10.2307/20086857.

- ↑ Faber, Richard and Bedford, Elizabeth. Domestic Programs of the American Presidents: A Critical Evaluation, p. 81 (McFarland 2008): "While other presidential candidates have received a plurality of popular votes and lost, Tilden has been the only presidential candidate to receive a majority of the popular vote and lose."

- ↑ Jones, Stephen A.; Freedman, Eric (2011). Presidents and Black America. CQ Press. p. 218. ISBN 9781608710089.

In an eleventh-hour compromise between party leaders - considered the "Great Betrayal" by many blacks and southern Republicans ...

- ↑ Downs, 2012

- ↑ Calhoun, page 43

- ↑ Socolofsky & Spetter, page 13

- 1 2 3 "2000 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTORAL AND POPULAR VOTE". Federal Election Commission. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

- ↑ "Once Close to Clinton, Gore Keeps a Distance". The New York Times. 20 October 2000. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ↑ CNN, Wade Payson-Denney. "Who really won Bush-Gore election?". cnn.com. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ↑ Rockefeller, J. D. (2015-11-21). Donald Trump: Life and Business Lessons. J.D. Rockefeller. ISBN 9781519453945.

- ↑ Sherman, Jill (2017-04-01). Donald Trump: Outspoken Personality and President. Lerner Publications. ISBN 9781512438574.

- ↑ "Sanders backers frustrated by defeats at Orlando platform meeting". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ↑ Amy Tennery (February 4, 2016). "Trump accuses Cruz of stealing Iowa caucuses through 'fraud'". Reuters.

- ↑ "Clinton & Trump: Favorability Ratings". Real Clear Politics. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ↑ Tessa Berenson (November 9, 2016). "Third Parties Faded to the Background in a Shocking Election". Time.

- ↑ Warner, Claire. "Ralph Nader Got The Most Write-In Votes For President Ever, But Election Write-Ins Have A Long History". Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Courtney Kennedy; et al. "An Evaluation of 2016 Election Polls in the U.S." American Association for Public Opinion Research, Ad Hoc Committee on 2016 Election Polling.

- ↑ Trump stomps all over the Democrats' Blue Wall, CNN, November 9, 2016.

- 1 2 "Presidential Election Results: Donald J. Trump Wins". The New York Times. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ↑ "Electoral College Timeline of Key Dates" (PDF). National Archives and Records Administration's Office of the Federal Register.

- 1 2 "OFFICIAL 2016 PRESIDENTIAL GENERAL ELECTION RESULTS" (PDF). Federal Elections Commission. January 30, 2017. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

- 1 2 Shear, Michael D.; Huetteman, Emmarie (2017). "Trump Repeats Lie About Popular Vote in Meeting With Lawmakers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- ↑ Graves, Allison (November 18, 2016). "Fact-check: Did 3 million undocumented immigrants vote in this year's election?". PolitiFact. Poynter Institute. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- ↑ David Lauter, Trump revives debunked accusation of massive vote fraud in California, Los Angeles Times (April 5, 2018).

- ↑ Leip, David. "1824 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 26, 2005.

- 1 2 Trende, Sean (October 19, 2012). "Did JFK Lose the Popular Vote?". Real Clear Politics.

- ↑ Azari, Julia (November 10, 2016). "Most People Hate The Electoral College, But It's Not Going Away Soon". FiveThirtyEight.

- ↑ Fund, John (November 20, 2003). "A Minority President". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on November 23, 2003. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur. Robert Kennedy and His Times, p. 220 (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012).

- ↑ Schier, Steven. You Call This an Election?: America's Peculiar Democracy, p. 100 (Georgetown University Press, 2003).

- ↑ Colomer, Josep. Political Institutions: Democracy and Social Choice, pp. 104-106 (Oxford University Press, 2001).

External links

- Kurtzleben, Danielle. "How To Win The Presidency With 23 Percent Of The Popular Vote", NPR (November 2, 2016).

.jpg)

.jpg)