List of United States presidential assassination attempts and plots

Assassination attempts and plots on the President of the United States have been numerous, ranging from the early 1800s to the 2010s. More than 30 attempts to kill an incumbent or former president, or a president-elect have been made since the early 1800s. Four sitting presidents have been killed, all of them by gunshot: Abraham Lincoln (1865), James A. Garfield (1881), William McKinley (1901) and John F. Kennedy (1963). Additionally, two presidents have been injured in attempted assassinations, also by gunshot: Theodore Roosevelt (1912; former president at the time) and Ronald Reagan (1981).

Although the historian James W. Clarke has suggested that most American assassinations were politically motivated actions, carried out by rational men,[1] not all such attacks have been undertaken for political reasons.[2] Some attackers had questionable mental stability, and a few were judged legally insane.[3][4] Since the vice president has for more than a century been elected from the same political party as the president, the assassination of the president is unlikely to result in major policy changes. This may explain why political groups typically do not make such attacks.[5]

Presidents assassinated

Abraham Lincoln

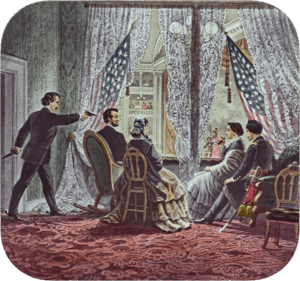

The assassination of President Lincoln took place on Good Friday, April 14, 1865, at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., at approximately 10:15 p.m.. John Wilkes Booth was a well-known actor and a Confederate sympathizer from Maryland; though he never joined the Confederate army, he had contacts with the Confederate secret service.[6] In 1864, Booth formulated a plan (very similar to one of Thomas N. Conrad previously authorized by the Confederacy)[7] to kidnap Lincoln in exchange for the release of Confederate prisoners. After attending an April 11, 1865, speech in which Lincoln promoted voting rights for blacks, an incensed Booth changed his plans and became determined to assassinate the president.[8] Learning that the President would be attending Ford's Theatre, Booth formulated a plan with co-conspirators to assassinate Lincoln at the theater, as well as Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William H. Seward at their homes. Lincoln attended the play Our American Cousin at Ford's Theatre.[9] As the President sat in his state box in the balcony, watching the play, with his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, and two guests, Major Henry Rathbone and his fiancée Clara Harris, Booth entered from behind, aimed a .44 caliber Derringer pistol at the back of Lincoln's head, and fired, mortally wounding the President. Rathbone momentarily grappled with Booth, but Booth stabbed him and escaped. The unconscious President was carried across the street from the theater to the Petersen House, where he remained in a coma for nine hours before dying the following morning at 7:22 a.m. on April 15.[10]

Beyond Lincoln's death the plot failed: Seward was only wounded and Johnson's would-be attacker lost his nerve.

After being on the run for 12 days, Booth was tracked down and found on April 26, 1865 by Union soldiers on a farm in Virginia, some 70 miles (110 km) south of Washington. After refusing to surrender to Union troops, Booth was shot and killed by Sergeant Boston Corbett. Several other conspirators were later hanged.

James A. Garfield

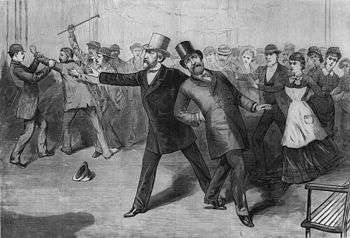

The assassination of President Garfield took place in Washington, D.C., at 9:30 a.m. on Saturday, July 2, 1881, less than four months after he took office. Charles J. Guiteau shot him twice, once in his right arm and once in his back, with a .442 Webley British Bulldog revolver, as the president was arriving at the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station. Garfield died 11 weeks later, on September 19, 1881, at 10:35 p.m., of complications caused by infections.

Guiteau was immediately arrested. After a highly publicized trial lasting from November 14, 1881 to January 25, 1882, he was found guilty and sentenced to death. A subsequent appeal was rejected, and he was executed by hanging on June 30, 1882 in the District of Columbia, two days before the first anniversary of the attempt. Guiteau was assessed during his trial as mentally unbalanced and possibly suffered from some kind of bipolar disorder or from the effects of syphilis on the brain. He claimed to have shot Garfield out of disappointment for being passed over for appointment as Ambassador to France. He attributed the president's victory in the election to a speech he wrote in support of Garfield.[11]

William McKinley

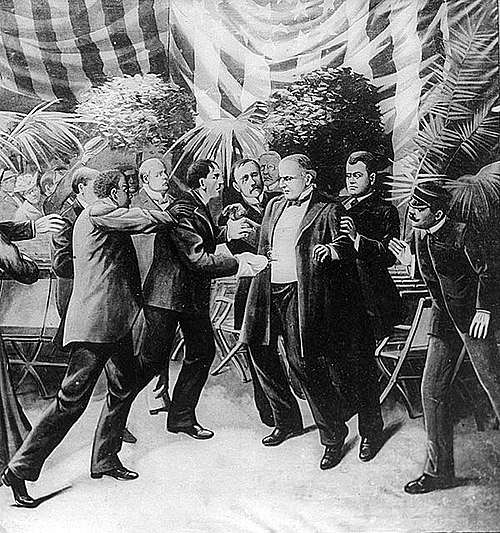

The assassination of President McKinley took place at 4:07 p.m. on Friday, September 6, 1901, at the Temple of Music in Buffalo, New York. McKinley, attending the Pan-American Exposition, was shot twice in the abdomen at close range by Leon Czolgosz, a self-proclaimed anarchist, who was armed with a .32 caliber revolver wrapped up in what seemed to be a bandage. The first bullet ricocheted off either a button or an award medal on McKinley's jacket and lodged in his sleeve but the second shot pierced his stomach. McKinley died seven days later, on September 14, 1901, at 2:15 a.m, after his condition rapidly declined.

Members of the crowd captured and subdued Czolgosz. Afterward, the 4th Brigade, National Guard Signal Corps, and police intervened, beating Czolgosz so severely it was initially thought he might not live to stand trial. On September 24, after a rushed, two-day trial in state court, Czolgosz was sentenced to death. He was executed by electric chair in Auburn Prison on October 29, 1901. Czolgosz's actions were politically motivated, although it remains unclear what outcome, if any, he believed the shooting would yield.

Following the assassination of President William McKinley, Congress directed the Secret Service to protect the President of the United States as part of its mandate.

John F. Kennedy

The assassination of President Kennedy took place on Friday, November 22, 1963, in Dallas, Texas, at 12:30 p.m. CST (18:30 UTC), while riding in a presidential motorcade in Dealey Plaza.[12] Kennedy was riding with his wife Jacqueline, Texas Governor John Connally, Connally's wife, Nellie, and two Secret Service agents, when he was fatally shot in the neck and head. He was the only assassinated president to die on the same day of his injuries. Governor Connally was seriously wounded in the attack. The motorcade rushed to Parkland Memorial Hospital where President Kennedy was pronounced dead about thirty minutes after the shooting; Connally recovered from his injuries.

Former U.S. Marine and Marxist[13] Lee Harvey Oswald was arrested by members of the Dallas Police Department about 70 minutes after the initial shooting. Oswald was charged under Texas state law with the murder of Kennedy as well as that of a Dallas policeman, J. D. Tippit, who had been fatally shot a short time after the assassination. At 11:21 a.m. Sunday, November 24, 1963, as live television cameras covered his transfer to the Dallas County Jail, Oswald was shot in the basement of Dallas Police Headquarters by Jack Ruby, a Dallas nightclub operator. Oswald was taken to Parkland Memorial Hospital where he soon died. Ruby was found guilty of murder with malice and sentenced to death by the electric chair. In October 1966, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals reversed the conviction on the grounds of improper admission of testimony and the fact that Ruby could not have received a fair trial in Dallas at the time due to excessive publicity. A new trial was scheduled to take place in Wichita Falls, Texas, in February 1967 but he became ill and was admitted to Parkland Hospital (the same place where Kennedy and Oswald had died). He was diagnosed with lung cancer. On January 3, 1967, he died at age 55 from a blood clot in his lung.

After a ten-month investigation, the Warren Commission concluded that Kennedy was assassinated by Oswald, that Oswald had acted entirely alone, and that Ruby had acted alone in killing Oswald. Nonetheless, polls conducted from 1966 to 2004 found that up to 80 percent of Americans have suspected that there was a plot or cover-up.[14][15] Doubts and conspiracy theories persist to the present.

Assassination plots and attempts

Andrew Jackson

- January 30, 1835: Just outside the Capitol Building, a house painter named Richard Lawrence attempted to shoot Jackson with two pistols, both of which misfired. Lawrence was apprehended after Jackson beat him severely with his cane. Lawrence was found not guilty by reason of insanity and confined to a mental institution until his death in 1861.[16]

Abraham Lincoln

- February 23, 1861: The Baltimore Plot was an alleged conspiracy to assassinate President-elect Abraham Lincoln en route to his inauguration. Allan Pinkerton's National Detective Agency played a key role in protecting the president-elect by managing Lincoln's security throughout the journey. Although scholars debate whether the threat was real, Lincoln and his advisers took actions to ensure his safe passage through Baltimore.

- August 1864: A lone rifle shot fired by an unknown sniper missed Lincoln's head by inches (passing through his hat) as he rode in the late evening, unguarded, north from the White House three miles (5 km) to the Soldiers' Home (his regular retreat where he would work and sleep before returning to the White House the following morning). Near 11:00 pm, Private John W. Nichols of the Pennsylvania 150th Volunteers, the sentry on duty at the gated entrance to the Soldiers' Home grounds, heard the rifle shot and moments later saw the president riding toward him "bareheaded". Lincoln described the matter to Ward Lamon, his old friend and loyal bodyguard.[17][18]

William Howard Taft

- 1909: Taft and Porfirio Díaz planned a summit in El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, a historic first meeting between a U.S. president and a Mexican president and also the first time an American president would cross the border into Mexico.[19] Diaz requested the meeting to show U.S. support for his planned eighth run as president, and Taft agreed to support Diaz in order to protect the several billion dollars of American capital then invested in Mexico.[20] Both sides agreed that the disputed Chamizal strip connecting El Paso to Ciudad Juárez would be considered neutral territory with no flags present during the summit, but the meeting focused attention on this territory and resulted in assassination threats and other serious security concerns.[21] The Texas Rangers, 4,000 U.S. and Mexican troops, U.S. Secret Service agents, FBI agents and U.S. Marshals were all called in to provide security.[22] An additional 250 private security detail led by Frederick Russell Burnham, the celebrated scout, was hired by John Hays Hammond. Hammond was a close friend of Taft from Yale and a former candidate for U.S. Vice-President in 1908 who, along with his business partner Burnham, held considerable mining interests in Mexico.[23][24][25] On October 16, the day of the summit, Burnham and Private C.R. Moore, a Texas Ranger, discovered a man holding a concealed palm pistol standing at the El Paso Chamber of Commerce building along the procession route.[26] Burnham and Moore captured and disarmed the would-be assassin within only a few feet of Taft and Díaz.[27]

Theodore Roosevelt

- October 14, 1912: Three and a half years after he left office, Roosevelt was running for President as a member of the Progressive Party. While campaigning in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, John Flammang Schrank, a saloon-keeper from New York who had been stalking him for weeks, shot Roosevelt once in the chest with a .38-caliber Colt Police Positive Special revolver. The 50-page text of his campaign speech titled "Progressive Cause Greater Than Any Individual", folded over twice in Roosevelt's breast pocket and a metal glasses case slowed the bullet, saving his life. Schrank was immediately disarmed, captured and might have been lynched had Roosevelt not shouted for Schrank to remain unharmed.[28] Roosevelt assured the crowd he was all right, then ordered police to take charge of Schrank and to make sure no violence was done to him.[29]

- Roosevelt, as an experienced hunter and anatomist, correctly concluded that since he was not coughing blood, the bullet had not reached his lung, and he declined suggestions to go to the hospital immediately. Instead, he delivered his scheduled speech with blood seeping into his shirt.[30][31] He spoke for 90 minutes before completing his speech and accepting medical attention. His opening comments to the gathered crowd were, "Ladies and gentlemen, I don't know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot, but it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose."[32][33][33] [34] Afterwards, probes and an x-ray showed that the bullet had lodged in Roosevelt's chest muscle, but did not penetrate the pleura. Doctors concluded that it would be less dangerous to leave it in place than to attempt to remove it, and Roosevelt carried the bullet with him for the rest of his life.[35][36] He spent two weeks recuperating before returning to the campaign trail. Despite his tenacity, Roosevelt ultimately lost his bid for reelection.[37]

- At Schrank's trial, the would-be assassin claimed that William McKinley had visited him in a dream and told him to avenge his assassination by killing Roosevelt. He was found legally insane and was institutionalized until his death in 1943.[38]

Herbert Hoover

- On November 19, 1928,[39] President-elect Hoover embarked on a ten-nation "goodwill tour" of Central and South America.[40] While crossing the Andes mountains from Chile, an assassination plot by Argentine anarchists was thwarted. The group was led by Severino Di Giovanni, who planned to blow up his train as it crossed the Argentinian central plain. The plotters had an itinerary but the bomber was arrested before he could place the explosives on the rails. Hoover professed unconcern, tearing off the front page of a newspaper that revealed the plot and explaining, "It's just as well that Lou shouldn't see it,"[41] referring to his wife. His complimentary remarks on Argentina were well received in both the host country and in the press.[42]

Franklin D. Roosevelt

- On February 15, 1933, in Miami, Florida, Giuseppe Zangara fired five shots at Roosevelt, seventeen days before Roosevelt's first presidential inauguration. Although Zangara did not wound the President-elect, he did kill Chicago Mayor Anton Cermak and wounded five other people. Zangara was found guilty of murder and was executed on March 20, 1933. It has never been determined who was Zangara's target, and most assumed at first that he had been shooting at the President-elect. Another theory, is that it may have been ordered by the imprisoned Al Capone.[43][44]

- Soviet authorities claimed to have discovered a German plan to assassinate Roosevelt at the upcoming Tehran Conference in 1943.[45]

Harry S. Truman

- Summer 1947: During the pending of the independence of Israel, the Zionist Stern Gang was believed to have sent a number of letter bombs addressed to the president and high-ranking staff at the White House. The Secret Service had been alerted by British intelligence after similar letters had been sent to high-ranking British officials and the Gang claimed credit.The mail room of the White House intercepted the letters and the Secret Service defused them. At the time, the incident was not publicized. Truman's daughter Margaret confirmed the incident in her biography of Truman published in 1972. It had earlier been told in a memoir by Ira R.T. Smith, who worked in the mail room.[46]

- November 1, 1950: Two Puerto Rican pro-independence activists, Oscar Collazo and Griselio Torresola, attempted to kill Truman at the Blair House, where Truman lived while the White House was being renovated. In the attack, Torresola mortally wounded White House Policeman Leslie Coffelt, who killed the attacker with a shot to the head. Torresola also wounded White House Policeman Joseph Downs. Collazo wounded another officer, and survived with serious injuries. Truman was not harmed, but he was placed at a huge risk. He commuted Collazo's death sentence after conviction in a federal trial to life in prison. In 1979, President Jimmy Carter commuted it to time served.[47]

John F. Kennedy

- December 11, 1960: While vacationing in Palm Beach, Florida, President-elect John F. Kennedy was threatened by Richard Paul Pavlick, a 73-year-old former postal worker driven by hatred of Catholics. Pavlick intended to crash his dynamite-laden 1950 Buick into Kennedy's vehicle, but he changed his mind after seeing Kennedy's wife and daughter bid him goodbye.[48] Pavlick was arrested three days later by the Secret Service after being stopped for a driving violation; police found the dynamite in his car and arrested him.[49] On January 27, 1961, Pavlick was committed to the United States Public Health Service mental hospital in Springfield, Missouri, then was indicted for threatening Kennedy's life seven weeks later.[49] Charges against Pavlick were dropped on December 2, 1963, ten days after Kennedy's assassination in Dallas.[49] Judge Emett Clay Choate ruled that Pavlick was unable to distinguish between right and wrong in his actions, but kept him in the mental hospital. The federal government also dropped charges in August 1964, and Pavlick was eventually released from the New Hampshire State Mental Hospital on December 13, 1966.[49][50][51]

Richard Nixon

- April 13, 1972: Arthur Bremer carried a firearm to an event intending to shoot Nixon, but was put off by strong security. A few weeks later, he instead shot and seriously injured the Governor of Alabama, George Wallace, who was paralyzed for the rest of his life until his death in 1998. Three other people were unintentionally wounded. Bremer served 35 years in prison for the shooting of Governor Wallace.[52]

- February 22, 1974: Samuel Byck planned to kill Nixon by crashing a commercial airliner into the White House.[53] He hijacked the plane on the ground by force after killing a police officer, and was told that it could not take off with the wheel blocks still in place. After he shot both pilots (one later died), an officer, Charles 'Butch' Troyer, shot Byck through the plane's door window. He survived long enough to kill himself by shooting.

Gerald Ford

- September 5, 1975: On the northern grounds of the California State Capitol, Lynette "Squeaky" Fromme, a follower of Charles Manson, drew a Colt M1911 .45 caliber pistol on Ford when he reached to shake her hand in a crowd. She had four cartridges in the pistol's magazine but none in the firing chamber, and as a result, the gun did not fire. She was quickly restrained by Secret Service agent Larry Buendorf. Fromme was sentenced to life in prison, but was released from custody on August 14, 2009 (two years and 8 months after Ford's death in 2006).[54]

- September 22, 1975: In San Francisco, California, only 17 days after Fromme's attempt, Sara Jane Moore fired a revolver at Ford from 40 feet (12 m) away.[55] A bystander, Oliver Sipple, grabbed Moore's arm and the shot missed Ford, striking a building wall and slightly injuring taxi driver John Ludwig.[56] Moore was tried and convicted in federal court, and sentenced to prison for life. She was paroled from a federal prison on December 31, 2007 after serving more than 30 years, one year and five days after Ford's natural death.

Jimmy Carter

- Raymond Lee Harvey was an Ohio-born unemployed American drifter. He was arrested by the Secret Service after being found carrying a starter pistol with blank rounds, ten minutes before Carter was to give a speech at the Civic Center Mall in Los Angeles on May 5, 1979. Harvey had a history of mental illness,[57] but police had to investigate his claim that he was part of a four-man operation to assassinate the president.[58] According to Harvey, he fired seven blank rounds from the starter pistol on the hotel roof on the night of May 4 to test how much noise it would make. He claimed to have been with one of the plotters that night, whom he knew as "Julio". (This man was later identified as a 21-year-old illegal immigrant from Mexico, who gave the name Osvaldo Espinoza Ortiz.)[57] At the time of his arrest, Harvey had eight spent rounds in his pocket, as well as 70 unspent blank rounds for the gun.[59] Harvey was jailed on a $50,000 bond, given his transient status, and Ortiz was alternately reported as being held on a $100,000 bond as a material witness[57] or held on a $50,000 bond being charged with burglary from a car.[59] Charges against the pair were ultimately dismissed for a lack of evidence.[60]

- John Hinckley Jr. came close to shooting Carter during his re-election campaign, but he lost his nerve. He would later attempt to kill President Ronald Reagan in March 1981.[61][62]

Ronald Reagan

- March 30, 1981: As Ronald Reagan returned to his limousine after speaking at the Washington Hilton hotel, he and three others were shot by John Hinckley, Jr. Reagan was struck by a single bullet that broke a rib, punctured a lung, and caused serious internal bleeding, but he recovered quickly.

- Hinckley was arrested at the scene, and later said he had wanted to kill Reagan to impress actress Jodie Foster. He was deemed mentally ill and confined to an institution. Besides Reagan, White House Press Secretary James Brady, Secret Service agent Tim McCarthy, and police officer Thomas Delahanty were also wounded. All three survived, but Brady suffered brain damage and was permanently disabled; Brady's death in 2014 was considered homicide because it was ultimately caused by this injury.[63] Hinckley was released from institutional psychiatric care at St. Elizabeth Hospital in Washington, D.C., on September 10, 2016.

George H. W. Bush

- April 13, 1993: Fourteen men believed to be working for Saddam Hussein smuggled bombs into Kuwait, planning to assassinate former President Bush by a car bomb during his visit to Kuwait University three months after he had left office (in January 1993).[64] The plot was foiled when Kuwaiti officials found the bomb and arrested the suspected assassins. Two of the suspects, Wali Abdelhadi Ghazali and Raad Abdel-Amir al-Assadi, retracted their confessions at the trial, claiming that they were coerced.[65] There is evidence that the Iraqi Intelligence Service, particularly Directorate 14, was behind the plot.[66] Then-president Bill Clinton responded by launching a cruise missile attack on an Iraqi intelligence building in Baghdad. The plot was used as one of the justifications for the Iraq Resolution.

Bill Clinton

- January 21, 1994: Ronald Gene Barbour, a retired military officer and freelance writer, plotted to kill Clinton while the President was jogging. Barbour returned to Florida a week later without having fired the shots at the president, who was on a state visit to Russia.[67] Barbour was sentenced to five years in prison and was released in 1998.

- September 12, 1994: Frank Eugene Corder flew a stolen single-engine Cessna onto the White House lawn and crashed into a tree. Corder, a truck driver from Maryland who reportedly had alcohol problems, allegedly tried to hit the White House. He was killed in the crash. The President and First Family were not home at the time.[68]

- October 29, 1994: Francisco Martin Duran fired at least 29 shots with a semi-automatic rifle at the White House from a fence overlooking the north lawn, thinking that Clinton was among the men in dark suits standing there (Clinton was inside). Three tourists, Harry Rakosky, Ken Davis and Robert Haines, tackled Duran before he could injure anyone. Found to have a suicide note in his pocket, Duran was sentenced to 40 years in prison.[69]

- 1996: During his visit to the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum in Manila, Clinton's motorcade was rerouted before it was to drive over a bridge. Service officers had intercepted a message suggesting that an attack was imminent, and Lewis Merletti, the director of the Secret Service, ordered the motorcade to be re-routed. An intelligence team later discovered a bomb under the bridge. Subsequent U.S. investigation "revealed that [the plot] was masterminded by a Saudi terrorist living in Afghanistan named Osama bin Laden".[70]

George W. Bush

- February 7, 2001: While President George W. Bush was in the White House, Robert Pickett, standing outside the perimeter fence, discharged a number of shots from a weapon in the direction of the White House. He was sentenced to three years in prison.[71] The attempt happened within a month of the president taking office.

- May 10, 2005: While President Bush was giving a speech in the Freedom Square in Tbilisi, Georgia, Vladimir Arutyunian threw a live Soviet-made RGD-5 hand grenade toward the podium. The grenade had its pin pulled, but did not explode because a red tartan handkerchief was wrapped tightly around it, preventing the safety lever from detaching.[72] After escaping that day, Arutyunian was arrested in July 2005. During his arrest, he killed an Interior Ministry agent. He was convicted in January 2006 and given a life sentence.[73][74]

Barack Obama

- April 2009: A plot to assassinate Obama at the Alliance of Civilizations summit in Istanbul, Turkey was discovered after a man of Syrian origins carrying forged Al-Jazeera TV press credentials was found. The man confessed to the Turkish security services details of his plan to kill Obama with a knife with three alleged accomplices.[75]

- November 2011: Oscar Ramiro Ortega-Hernandez hit the White House with several rounds fired from a semi-automatic rifle. No one was injured. However, a window was broken.[76] He was sentenced to 25 years in prison.[77]

- April 2013: Another attempt was made when a letter laced with ricin, a deadly poison, was sent to President Obama.[78]

Donald Trump

- October 2018: William Clyde Allen III, a U.S. Navy veteran, sent a letter containing castor beans to President Trump. The letter did not reach the White House as it was seized by the Secret Service. Allen was arrested on October 3 in Utah.[79][80][81]

Deaths rumored to be assassinations

Zachary Taylor

On July 4, 1850, President Zachary Taylor fell ill and was diagnosed by his physicians with cholera morbus, a term that included diarrhea and dysentery but not true cholera. Cholera, typhoid fever and food poisoning have all been indicated as the source of the president's ultimately fatal gastroenteritis. A hasty snack of iced milk, cold cherries and pickles consumed at an Independence Day celebration might have been the culprit.[82] Taylor died five days later in the White House on July 9, 1850, at 10:35 p.m. (22:35).[83]

In the late 1980s, author Clara Rising theorized that Taylor was murdered by poison; she was able to convince Taylor's closest living relative, as well as the coroner of Jefferson County, Kentucky, Dr. Richard Greathouse, to order an exhumation. On June 17, 1991, Taylor's remains were exhumed from the vault at the Zachary Taylor National Cemetery in Louisville, Kentucky. Radiological studies were conducted of the remains before small samples of hair, fingernail, and other tissues were removed. The remains were then retinterred. The samples were sent to Oak Ridge National Laboratory, where neutron activation analysis revealed traces of arsenic, but at levels less than one percent of the level expected in a death by poisoning.[84]

Warren G. Harding

In June 1923, President Warren G. Harding set out on a cross-country "Voyage of Understanding", planning to meet with citizens and explain his policies. During this trip, he became the first president to visit Alaska, which was then a U.S. territory.[85]

Rumors of corruption in the Harding administration were beginning to circulate in Washington by 1923, and Harding was profoundly shocked by a long message he received while in Alaska, apparently detailing illegal activities by his own cabinet that were allegedly unknown to him. At the end of July, while traveling south from Alaska through British Columbia, he developed what was thought to be a severe case of food poisoning. He gave the final speech of his life to a large crowd at the University of Washington Stadium (now Husky Stadium) at the University of Washington campus in Seattle, Washington. A scheduled speech in Portland, Oregon, was canceled. The President's train proceeded south to San Francisco. Upon arriving at the Palace Hotel, he developed pneumonia. Harding died in his hotel room of either a heart attack or a stroke at 7:35 p.m. (19:35) on August 2, 1923. The formal announcement, printed in The New York Times of that day, stated: "A stroke of apoplexy was the cause of death." He had been ill exactly one week.[86]

Naval physicians surmised that Harding had suffered a heart attack. The Hardings' personal medical advisor, homeopath and Surgeon General Charles E. Sawyer, disagreed with the diagnosis. His wife, Florence Harding, refused permission for an autopsy, which soon led to speculation that the President had been the victim of a plot, possibly carried out by his wife, as Harding apparently had been unfaithful to the First Lady. Gaston B. Means, an amateur historian and gadfly, noted in his book The Strange Death of President Harding (1930) that the circumstances surrounding his death led to suspicions that he had been poisoned. A number of individuals attached to him, both personally and politically, would have welcomed Harding's death, as they would have been disgraced in association by Means' assertion of Harding's "imminent impeachment".

See also

- Assassination of Robert F. Kennedy, Democratic presidential candidate, on June 5, 1968

- Attempted assassination of Donald Trump, then presumptive Republican nominee for president, on June 18, 2016

- Attempted assassination of George Wallace, Democratic presidential candidate, on May 15, 1972

- Attempted assassination of Thomas R. Marshall, vice president, on July 2, 1915

- Curse of Tippecanoe

- Kennedy curse

- List of assassinated and executed heads of state and government

- List of incidents of political violence in Washington, D.C.

- List of White House security breaches

- Threatening the President of the United States

References

- ↑ Clarke, J. W. (1982). American Assassins: The Darker Side of Politics. Princeton University Press.

- ↑ E.g., Assassinations, presidential Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.. Answers.com. Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- ↑ E.g., Ben Dennison, "The 6 Most Utterly Insane Attempts to Kill a US President" Archived February 9, 2016, at the Wayback Machine., Cracked, October 21, 2008. Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- ↑ "Praying for God to Kill the President", TFN Insider, Texas Freedom Network, Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- ↑ Lawrence Zelic Freedman (March 1983). "The Politics of Insanity: Law, Crime, and Human Responsibility". Political Psychology. 4 (1): 171–178. doi:10.2307/3791182. JSTOR 3791182.

- ↑ Donald (1996), pp. 586–587.

- ↑ Donald (1996), p. 587.

- ↑ Harrison (2000), pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Donald (1996), pp. 594–597.

- ↑ "Lincoln Papers: Lincoln Assassination: Introduction". Memory.loc.gov. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- ↑ Peskin, Allan (1978). Garfield. Kent State University Press. p. 587. ISBN 0-87338-210-2.

- ↑ Stokes 1979, pp. 21.

- ↑ "Lee Harvey Oswald". Biography.com. Retrieved 2017-06-26.

- ↑ Gary Langer (November 16, 2003). "John F. Kennedy's Assassination Leaves a Legacy of Suspicion" (PDF). ABC News. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 26, 2011. Retrieved May 16, 2010.

- ↑ Jarrett Murphy, "40 Years Later: Who Killed JFK?" Archived November 17, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., CBS News, November 21, 2003.

- ↑ "Trying to Assassinate President Jackson". American Heritage. January 30, 2007. Archived from the original on October 24, 2008. Retrieved May 6, 2007.

- ↑ Flood, Charles Bracelen (2010). 1864: Lincoln at the Gates of History, pp 266-267. Simon & Schuster Lincoln Library ISBN 1416552286

- ↑ Sandburg, Carl (1954). Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years and the War Years One-Volume Edition. pp 599-600. Harcourt ISBN 0-15-602611-2

- ↑ Harris 2009, p. 1.

- ↑ Harris 2009, p. 2.

- ↑ Harris 2009, p. 14.

- ↑ Harris 2009, p. 15.

- ↑ Hampton 1910

- ↑ van Wyk 2003, pp. 440–446.

- ↑ "Mr. Taft's Peril; Reported Plot to Kill Two Presidents". Daily Mail. London. October 16, 1909. ISSN 0307-7578.

- ↑ Hammond 1935, pp. 565-66.

- ↑ Harris 2009, p. 213.

- ↑ "The Bull Moose and related media". Archived from the original on March 8, 2010. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- ↑ Remey, Oliver E.; Cochems, Henry F.; Bloodgood, Wheeler P. (1912). The Attempted Assassination of Ex-President Theodore Roosevelt. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: The Progressive Publishing Company. p. 192.

- ↑ "Medical History of American Presidents". Doctor Zebra. Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- ↑ John Gurda. Cream City Chronicles: Stories of Milwaukee's Past. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2016, pp. 189-191.

- ↑ "Excerpt", Detroit Free Press, History buff .

- 1 2 "It Takes More Than That to Kill a Bull Moose: The Leader and The Cause". Theodore Roosevelt Association. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ↑ "Home - Theodore Roosevelt Association". Theodoreroosevelt.org. February 1, 2013. Archived from the original on January 29, 2013. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- ↑ "Roosevelt Timeline". Theodore Roosevelt. Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- ↑ Timeline of Theodore Roosevelt's Life by the Theodore Roosevelt Association at www.theodoreroosevelt.org

- ↑ "Justice Story: Teddy Roosevelt survives assassin when bullet hits folded speech in his pocket". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on January 30, 2013. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- ↑ "John Schrank". Classic Wisconsin. Archived from the original on April 20, 2016. Retrieved May 6, 2007.

- ↑ Jeansonne, Glen (2012). The Life of Herbert Hoover: Fighting Quaker, 1928-1933. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-1-137-34673-5. Retrieved May 20, 2016.

- ↑ "Travels of President Herbert C. Hoover". U.S. Department of State Office of the Historian. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- ↑ "The Museum Exhibit Galleries, Gallery 5: The Logical Candidate, The President-Elect". West Branch, Iowa: Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- ↑ "National Affairs: Hoover Progress". Time. December 24, 1928. Archived from the original on June 24, 2013.

- ↑ "Bohemian National Cemetery: Mayor Anton Cermak". www.graveyards.com. Archived from the original on August 9, 2016. Retrieved June 24, 2017.

- ↑ "Sam 'Momo' Giancana - Live and Die by the Sword". Crime Library. Archived from the original on February 8, 2007. Retrieved May 7, 2007.

- ↑

Mayle, Paul D. (1987). Eureka Summit: Agreement in Principle and the Big Three at Tehran, 1943. University of Delaware Press. p. 57. ISBN 9780874132953. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

[...] the Russians had uncovered a plot - German agents in Tehran had learned of Roosevelt's presence and were making plans for acion that was likely to take the form of an assassination attempt on one or more of the Big Three while they were in transit between meetings.

- ↑ AP, "Jews Sent Truman Letter Bombs, Book Tells", Tri-City Herald, December 1, 1972, accessed December 11, 2012

- ↑ Hibbits, Bernard. "Presidential Pardons". Jurist: The Legal Education Network. University of Pittsburgh School of Law. Archived from the original on November 17, 2007. Retrieved December 16, 2010.

- ↑ "Kennedy presidency almost ended before he was inaugurated". The Blade. Toledo, Ohio. November 21, 2003. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved May 6, 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 Oliver, Willard; Marion, Nancy E. (2010). Killing the President: Assassinations, Attempts, and Rumored Attempts on U.S. Commanders-in-Chief: Assassinations, Attempts, and Rumored Attempts on U.S. Commanders-in-Chief. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313364754.

- ↑ Hunsicker, A. (2007). The Fine Art of Executive Protection: Handbook for the Executive Protection Officer. Universal-Publishers. ISBN 9781581129847.

- ↑ Ling, Peter J. (2013). John F. Kennedy. Routledge. ISBN 9781134713257.

- ↑ "Man Who Shot George Wallace To Be Freed". CBS. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- ↑ "9/11 report notes". 9/11 Commission. Archived from the original on April 12, 2016. Retrieved May 6, 2007.

- ↑ "1975 : Ford assassination attempt thwarted". History Channel. Archived from the original on May 2, 2009. Retrieved May 6, 2007.

- ↑ "1975 : President Ford survives second assassination attempt". History Channel. Archived from the original on January 3, 2013. Retrieved May 8, 2007.

- ↑ "The Imperial Presidency 1972-1980". Archived from the original on April 22, 1999. Retrieved May 8, 2007.

- 1 2 3 "Skid Row Plot: A scheme to kill Carter?" Archived August 23, 2013, at the Wayback Machine., Time May 21, 1979.

- ↑ "The Plot to Kill Carter", Newsweek May 21, 1979.

- 1 2 "Alleged Carter death plot: man charged", The Sydney Morning Herald May 10, 1979.

- ↑ "Harvey / "Carter Assassination Plot", CBS News broadcast". Vanderbilt Television News Archive. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved June 24, 2017.

- ↑ "John Hinckley Jr.: Hunting Carter and Reagan". History on the Net. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ↑ Taubman, Philip. "Investigators Think Hinckley Stalked Carter". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ↑ "Medical examiner rules James Brady's death a homicide". Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 28, 2016. Retrieved June 24, 2017.

- ↑ Von Drehle, David & Smith, R. Jeffrey (Jun 27, 1993). "U.S. Strikes Iraq for Plot to Kill Bush". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- ↑ "The Bush assassination attempt". Department of Justice/FBI Laboratory report. Archived from the original on April 2, 2007. Retrieved May 6, 2007.

- ↑ Duelfer, Charles (September 30, 2004). "IIS Undeclared Research on Poisons and Toxins for Assassination". Iraq Study Group Final Report. Globalsecurity.org. Archived from the original on January 11, 2008. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- ↑ "Unemployed Man Is Charged With Threat to Kill President". The New York Times. February 19, 1994. Archived from the original on May 17, 2017.

- ↑ Dowd, Maureen (September 14, 1994). "Crash at the White House: The Overview". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 24, 2009. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- ↑ "Summary Statement of Facts (The September 12, 1994 Plane Crash and The October 29, 1994 Shooting) Background Information on the White House Security Review". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved May 6, 2007.

- ↑ Leonard, Tom (Dec 22, 2009). "Osama bin Laden came within minutes of killing Bill Clinton". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on December 25, 2009. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- ↑ "U.S. presidential assassinations and attempts". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 4, 2013. Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- ↑ US FBI report into the attack and investigation Archived April 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ "Bush grenade attacker gets life". CNN. January 11, 2006. Archived from the original on July 4, 2008. Retrieved May 6, 2007.

- ↑ "The case of the failed hand grenade attack". FBI Press Room. January 11, 2006. Archived from the original on April 11, 2007. Retrieved May 6, 2007.

- ↑ Ed Henry (April 6, 2009). "Plot to assassinate Obama foiled in Turkey". CNN. Archived from the original on July 3, 2016. Retrieved June 21, 2016.

- ↑ Leonnig, Carol D. (September 27, 2014). "Secret Service fumbled response after gunman hit White House residence in 2011". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 8, 2016. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- ↑ "Oscar Ramiro Ortega-Hernandez, man who shot at White House, gets 25 years". Fox News Channel. Associated Press. March 31, 2014. Archived from the original on January 11, 2015. Retrieved March 10, 2017.

- ↑ "FBI confirms letters to Obama, others contained ricin". CNN. Archived from the original on August 25, 2013. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- ↑ Barr, Luke (5 October 2018). "Man accused of sending letters laced with ricin 'wanted to send a message'". ABC News. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ↑ Whitehurst, Lindsay (3 October 2018). "Authorities Arrest Navy Veteran in Connection With Suspicious Envelopes Sent to President Trump". Time. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ↑ Copp, Tara (3 October 2018). "Navy vet arrested for allegedly trying to poison Mattis and the Navy's top officer". Military Times. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ↑ "The bug that poisoned the President". Ross Anderson. Feb 21, 2011. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved September 27, 2016.

- ↑ Baeur, Jack (August 1, 1993). Zachary Taylor: Soldier, Planter, Statesman of the Old Southwest. p. 316.

- ↑ Author unknown (date unknown). "President Zachary Taylor and the Laboratory: Presidential Visit from the Grave" in "Chapter 9: Global Outreach". Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Originally retrieved from "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 28, 2010. Retrieved November 2, 2010. . Retrieved from "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 28, 2011. Retrieved April 15, 2016. .

- ↑ Reeve, W. Paul (1995-07). President Harding's 1923 Visit to Utah. History Blazer, July 1995. Retrieved from "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 2, 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-14. .

- ↑ "Harding a Farm Boy Who Rose by Work". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 15, 2009. Retrieved July 21, 2007.

Nominated for the Presidency as a compromise candidate and elected by a tremendous majority because of a reaction against the policies of his predecessor, Warren Gamaliel Harding, twenty-ninth President of the United States, owed his political elevation largely to his engaging personal traits, his ability to work in harmony with the leaders of his party, and the fact that he typified in himself the average prosperous American citizen.

Bibliography

- Hammond, John Hays (1935). The Autobiography of John Hays Hammond. New York: Farrar & Rinehart. ISBN 978-0-405-05913-1.

- Hampton, Benjamin B (April 1, 1910). "The Vast Riches of Alaska". Hampton's Magazine. Vol. 24 no. 1.

- Harris, Charles H. III; Sadler, Louis R. (2009). The Secret War in El Paso: Mexican Revolutionary Intrigue, 1906-1920. Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-4652-0.

- van Wyk, Peter (2003). Burnham: King of Scouts. Victoria, B.C., Canada: Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4120-0901-0.