United States presidential election, 1788–89

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

69 electoral votes of the Electoral College 35 electoral votes needed to win | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 11.6%[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Presidential election results map. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state. (Note: North Carolina and Rhode Island had not yet ratified the Constitution, the New York legislature was deadlocked, and Vermont was operating as a de facto unrecognized state.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

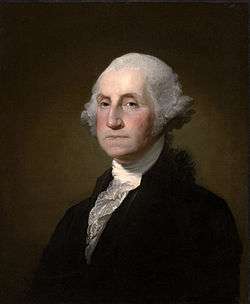

The United States presidential election of 1788–89 was the first quadrennial presidential election. It was held from Monday, December 15, 1788, to Saturday, January 10, 1789. It was conducted under the new United States Constitution, which had been ratified earlier in 1788. In the election, George Washington was unanimously elected for the first of his two terms as president, and John Adams became the first vice president.

Under the first federal Constitution ratified in 1781, known as the Articles of Confederation, the United States had no ceremonial head of state and the executive branch of government was part of the Congress, as it is in countries that use parliamentary systems of government. All federal power was reserved to the Congress of the Confederation, whose "President of the United States in Congress Assembled" was also chair of the de facto cabinet, called the Committee of the States. The United States Constitution created the offices of President of the United States and Vice President of the United States, and established that these offices would be elected separately from Congress. The Constitution established an Electoral College in which each elector would cast two votes, with no distinction made between electoral votes for president and electoral votes for vice president; this procedure would be modified in 1804 through the ratification of the Twelfth Amendment. The different states had varying methods for choosing presidential electors. Many states held a popular vote, but in other states, the state legislature appointed the electors.

Washington had distinguished himself in his role as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, and he was enormously popular. After Washington agreed to come out of retirement, it was widely assumed that he would be elected president. Washington did not select a running mate, and no formal political parties had arisen, so it was unclear who would become the first vice president. Prior to the election, Thomas Jefferson predicted that a popular Northern leader like Governor John Hancock of Massachusetts or Adams, a former minister to Great Britain who had represented Massachusetts in Congress, would be elected vice president. Anti-Federalist leaders like Patrick Henry (who ultimately did not run) and George Clinton, who had opposed ratification of the Constitution, also loomed as potential choices.

All 69 electors cast one vote for Washington, thus making his election unanimous. Adams won 34 electoral votes, making him the vice president-elect. The remaining 35 electoral votes were split among 10 different candidates, including John Jay, who finished in third place with 9 electoral votes. Washington was inaugurated in April 1789, thus beginning the first presidency.

Candidates

No official federal political parties existed at the time of the 1788–89 presidential election. Candidates might be Federalists, meaning they supported the ratification of the Constitution, or Anti-Federalists, meaning they opposed ratification. These designations were not established or organized political parties, but each forming faction supported Washington for President. During this time, the Federalists were called by name of Cosmopolitans, and the Anti-Federalists as Localists. The terms "Federalist" and "Anti-Federalists" were not commonplace names until later elections. Although the first election was not known for its extensive campaigning, the beginnings of lobbying can be seen in the first 1788–1789 election for president. Maryland is a telltale example of the early formation of the two-party system, as the unofficial parties campaigned locally, advertising their platforms in order to appeal to the German-speaking population, and as a result, received substantially higher voter turnout rates. Party advocates in some states lobbied through public forums, parades in the streets, and dinners, forming what George Washington warned against in his farewell address—polarizing factions.

The effects in the formation of these divisions almost became a determining factor on whether George Washington would actually run for a second term, which would have eliminated the current two-term tradition. More often than not, divisions during elections prior to 1788 were based not on political stance, but on the reputations and family names of the different candidates. Some states had virtually no factional competition, especially in the south, as states like Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina had little political organization. These states would at times go years without hosting elections, unless an election was deemed necessary by the state's legislative body.

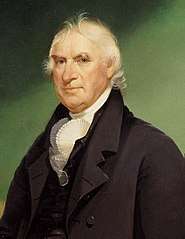

Federalist candidates

- John Adams, former Minister to Great Britain from Massachusetts

- John Jay, United States Secretary of Foreign Affairs from New York

- John Rutledge, former Governor of South Carolina

- John Hancock, Governor of Massachusetts

- Samuel Huntington, Governor of Connecticut

- Benjamin Lincoln, former U.S. Secretary of War from Massachusetts

- George Washington, former Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army from Virginia

Anti-Federalist candidates

- George Clinton, Governor of New York

General election

In the absence of political parties, there was no formal nomination process. The framers of the Constitution had presumed that Washington would be the first president, and there was no opposition to him since George Washington was widely seen as "essential to the successful operation of the new government." The nation was undivided, regardless of national beliefs or affiliations, in its decision of Washington as president, so it was of little curiosity to the nation that he won unanimously during the 1788–89 election. Alexander Hamilton, a devoted advocate of George Washington, stated to Washington that "...the point of light in which you stand home and abroad will make an infinite difference in the respectability in which the government will begin its operations in the alternative of your being or not being the head of state." Alexander Hamilton's letter to Washington is an attempt to persuade him to leave retirement on his farm in Mount Vernon, Virginia to run for the presidency, exemplifying the unanimous nature of George Washington's position as a candidate in the first election.

Less certain was the choice for the vice presidency, which contained no definite job description in the constitution. Although, the job title that came with being vice-president was as the head of the senate, unrelated to the executive branch. However, the Constitution did stipulate the position would be awarded to the runner-up in the presidential election. Because Washington was from Virginia, many assumed that a vice president would be chosen from one of the northern states to ease sectional tensions. In an August 1788 letter, U.S. Minister to France Thomas Jefferson wrote that he considered John Adams and John Hancock, both prominent citizens from Massachusetts, to be the top contenders. Jefferson suggested John Jay, James Madison, and John Rutledge as other possible candidates.[2]

Voter turnout was particularly low in the first election. Experts estimate that only 1.8-6% of the population participated. This was not due to a general lack of interest in the election, but rather a general lack of voting status. There were many restrictions put on potential voters, reducing the pool of would-be voters to a mere fraction of the population. The eligible voting population was primarily made up of white, male landowners, most of whom were educated. Of the people who could potentially vote, few knew anything of running candidates due to the inability to communicate to masses of people during the 18th century, generally making informed voting nearly impossible. Those who were of a different religion or without property were considered unfit to vote due to the idea that they could be easily swayed for one candidate or another, or had the possibility of creating detrimental factions in opposition to the government. The average person was considered uneducated, which included women, slaves, non citizens, indentured servants, and individuals younger than the age of 21. The qualities of a voter that were considered essential for a voter fit the characteristics of a "gentleman," as property owners were considered to have a "stake in society," deeming them independent and morally adept enough to be considered responsible voters. Voting eligibility varied from colony to colony, such as in Virginia and Connecticut which required a man to acquire a larger amount of property in order to hold different positions in office. The most common form of determining eligibility was the "forty pound rule", a common English practice that requires of voters to own forty pounds worth of land or receive a 5 percent return on the owned land. These eligible voter restrictions were made more inclusive with the later passage of the 15th amendment that removed racial affiliation as an eligible voter characteristic, and with the 19th amendment in 1920, which allowed for the suffrage of women.

No official laws were established barring immigrants who did not speak English from voting, but they were greatly discouraged from doing so by means of anti-immigrant rhetoric. The expectation was that any non-English speaking residents in the colonies were assumed to be ineligible due to property requirements. Regarding the 1788–1789 elections, eligible voting was determined by the type of Christianity that an individual affiliated with. Only Protestants, and in some instances certain denominations, could vote in certain colonies. For example, only congregationalists retained the right to vote in Massachusetts. Jews, Quakers, and especially Catholics could not vote legally in states such as Rhode Island and Virginia. However, this was not the case in every colony, as Pennsylvania allowed every citizen regardless of property to have the right to vote. Due to the sentiments of freedom and independence following the revolution, nominations became more localized and frequent, access to voting booths increased dramatically, and the first instances the Australian ballot began to pop up within the United States. Although many people were more apt to participate in local elections, nearly 90 percent of white males were able to vote in states like New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and New Hampshire.

An often unconsidered adversity in the Election of 1788–89 was great difficulty in communicating and convening for assembly due to "impassable, perilous roads, poorly-maintained bridges, and slow postal delivery." Voter turnout was inhibited significantly, as traveling to the nearest polling place could take days, and for many, leaving the farm unattended for prolonged periods of time could not be afforded in small middle-class agrarian households which relied on daily manual labor and upkeep of farmsteads. Congress also moved at a glacial rate due to these obstacles, and it even took two months for George Washington to learn that he had won the Presidency , and spent an entire week traveling from Virginia to New York to be sworn in as president. A total of four electoral votes were lost, two in Virginia as well as in Maryland, due to complications involving travel and private matters. These complications played a large role in the outcome of different aspects of the first election, ultimately causing necessary compromises that hindered the organizational efficiency of the new government.

Electors were chosen by the individual states, and each cast one vote for Washington. The electors used their second vote to cast a scattering of votes: while Adams won a plurality of these votes, a majority of the 69 electors voted for a candidate other than Adams. This was due largely to a scheme perpetrated by Alexander Hamilton, who feared that Adams would tie with Washington, throwing the election to the House of Representatives and embarrassing Washington and the new Constitution. Thus, Adams received only 34 of 69 votes, with the remaining 35 ballots split between ten other candidates.[3]

As the electors were being selected, rumors spread that there was an Anti-Federalist plot afoot to elect Richard Henry Lee or Patrick Henry president over Washington, with George Clinton as their choice for vice president. These rumors may have been encouraged by those sympathetic to the Federalists, who wished to discourage electors from voting for Clinton. If so, this strategy was effective: Clinton received only three electoral votes, possibly due to the fear that a vote for Clinton was effectively a vote against Washington.[4]

Only ten states out of the original thirteen cast electoral votes in this election. North Carolina and Rhode Island were ineligible to participate as they had not yet ratified the United States Constitution.[5] New York failed to appoint its allotment of eight electors because of a deadlock in the state legislature.[5]

Squabbles over the choice of the capital city lead to further party divisions, and cutthroat campaigning strategies were underway from slandering rumors to redistricting. The Massachusetts General Court had tampered with district borders to favor certain ideological inclinations, known today as "gerrymandering." Patrick Henry redrew districts for the House of Representatives election in favor of the Localists, aiding James Monroe to win the popular vote. Other slander in local elections that set the precedent for the Election of 1788 were the widespread conspiracy theories that often plagued candidates in running for office. Candidates published articles attacking the opposer. In South Carolina, a representative's character in terms of representing local interests was tarnished. Dave Ramsey, from New Jersey, contended in a three-way election to represent the Charleston district in 1788. Rumors circulated about his interests in "an emancipation of negroes," to which Ramsey rebutted with attempting to prove that his opponent, William Smith, was not considered a citizen under the constitution. Tensions on divisive issues increased regardless of the fact that there were no official party systems in place leading up to the 1788 election. Although these contentions played no part in Washington's unanimous vote, they revealed the strategies in which two groups attempted to secure positions in the Vice Presidential and legislative positions.

The founders attempted to create a society that supports more nationalistic world views that work to benefit the nation as a whole, as opposed to candidates self-interest and by simply representing the popular vote's local will. Considering the parochial nature of American society in the 18th century, it was assumed that most presidential elections would end up in the House of Representatives since electors would vote for locally known leaders and there would be no clear majority, hence the safeguarded structure of the electoral college, with one vote being mandatory out of state. The founders presumed that most elections would obtain no majority vote by the electors, as it was nearly depicted in the competitive election of John Adams as vice president. Yet, the House of Representatives has only chosen the President in 1801 and 1825 as opposed to most elections. Although the American political system did not pan out as the founders had hoped, the Election of 1788–1789 shaped the federal body experienced in the United States today. James Bryce described this in The American Commonwealth, "So hard it is to keep even a rigid constitution from warping and bending under the actual forces of politics."

Results

Popular vote

| Popular Vote(a), (b), (c) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | |

| Federalist electors | 39,624 | 90.5% |

| Anti-Federalist electors | 4,158 | 9.5% |

| Total | 43,782 | 100.0% |

Source: U.S. President National Vote. Our Campaigns. (February 11, 2006).

(a) Only 6 of the 10 states casting electoral votes chose electors by any form of popular vote.

(b) Less than 1.8% of the population voted: the 1790 Census would count a total population of 3.0 million with a free population of 2.4 million and 600,000 slaves in those states casting electoral votes in this election.

(c) Those states that did choose electors by popular vote had widely varying restrictions on suffrage via property requirements.

Electoral vote

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote(a), (b), (c) | Electoral vote(d), (e), (f) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | ||||

| George Washington | Non Partisan | Virginia | 43,782 | 100.0% | 69 |

| John Adams | Federalist | Massachusetts | — | — | 34 |

| John Jay | Federalist | New York | — | — | 9 |

| Robert H. Harrison | Federalist | Maryland | — | — | 6 |

| John Rutledge | Federalist | South Carolina | — | — | 6 |

| John Hancock | Federalist | Massachusetts | — | — | 4 |

| George Clinton | Anti Federalist | New York | — | — | 3 |

| Samuel Huntington | Federalist | Connecticut | — | — | 2 |

| John Milton | Federalist | Georgia | — | — | 2 |

| James Armstrong(g) | Federalist | Georgia(g) | — | — | 1 |

| Benjamin Lincoln | Federalist | Massachusetts | — | — | 1 |

| Edward Telfair | Anti Federalist | Georgia | — | — | 1 |

| Total | 43,782 | 100.0% | 138 | ||

| Needed to win | 35 | ||||

Source: "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 30, 2005. Source (Popular Vote): A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns 1787–1825[6]

(a) Only 6 of the 10 states casting electoral votes chose electors by any form of popular vote.

(c) Those states that did choose electors by popular vote had widely varying restrictions on suffrage via property requirements.

(d) The New York legislature failed to appoint its allotted 8 electors in time, so there were no voting electors from New York.

(e) Two electors from Maryland did not vote.

(f) One elector from Virginia did not vote and another elector from Virginia was not chosen because an election district failed to submit returns.

(g) The identity of this candidate comes from The Documentary History of the First Federal Elections (Gordon DenBoer (ed.), University of Wisconsin Press, 1984, p. 441). Several respected sources, including the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress and the Political Graveyard, instead show this individual to be James Armstrong of Pennsylvania. However, primary sources, such as the Senate Journal, list only Armstrong's name, not his state. Skeptics observe that Armstrong received his single vote from a Georgia elector. They find this improbable because Armstrong of Pennsylvania was not nationally famous—his public service to that date consisted of being a medical officer during the American Revolution and, at most, a single year as a Pennsylvania judge.

Results by state

Popular vote

| George Washington Federalist |

George Clinton Anti-Federalist |

State Total | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | ||||||||

| Connecticut | 7 | no popular vote | 7 | no popular vote | - | CT | ||||||||||

| Delaware | 3 | 685 | 100 | 3 | no ballots | 685 | DE | |||||||||

| Georgia | 5 | no popular vote | 5 | no popular vote | - | GA | ||||||||||

| Maryland | 8 | 5,539 | 71.63 | 6 | 2,193 | 28.37 | - | 7,732 | MD | |||||||

| Massachusetts | 10 | 17,740 | 100 | 10 | no ballots | 17,740 | MA | |||||||||

| New Hampshire | 5 | 5,909 | 100 | 5 | no ballots | 5,909 | NH | |||||||||

| New Jersey | 6 | no popular vote | 6 | no popular vote | - | NJ | ||||||||||

| New York | 8 | did not participate (legislature deadlocked) | - | NY | ||||||||||||

| North Carolina | 7 | did not participate (did not ratify Constitution) | - | NC | ||||||||||||

| Pennsylvania | 10 | 6,711 | 90.90 | 10 | 672 | 9.10 | - | 7,383 | PA | |||||||

| Rhode Island | 3 | did not participate (did not ratify Constitution) | - | RI | ||||||||||||

| South Carolina | 7 | no popular vote | 7 | no popular vote | - | SC | ||||||||||

| Virginia | 12 | 3,040 | 70.16 | 10 | 1,293 | 29.84 | - | 4,333 | VA | |||||||

| TOTALS: | 91 | 39,624 | 90.50 | 69 | 4,158 | 9.50 | 0 | 43,782 | US | |||||||

| TO WIN: | 35 | |||||||||||||||

Electoral vote

| State | Washington | Adams | Jay | Harrison | Rutledge | Hancock | Clinton | Huntington | Milton | Armstrong | Telfair | Lincoln |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connecticut | 7 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Delaware | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Georgia | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Maryland | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Massachusetts | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| New Hampshire | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| New Jersey | 6 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pennsylvania | 10 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| South Carolina | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Virginia | 10 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 69 | 34 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Electoral college selection

The Constitution, in Article II, Section 1, provided that the state legislatures should decide the manner in which their Electors were chosen. Different state legislatures chose different methods:[8]

| Method of choosing electors | State(s) |

|---|---|

| each elector appointed by the state legislature | Connecticut Georgia New Jersey New York(a) South Carolina |

|

Massachusetts |

| each elector chosen by voters statewide; however, if no candidate wins majority, state legislature appoints elector from top two candidates | New Hampshire |

| state is divided into electoral districts, with one elector chosen per district by the voters of that district | Virginia(b) Delaware |

| electors chosen at large by voters | Maryland Pennsylvania |

| state had not yet ratified the Constitution, so was not eligible to choose electors | North Carolina Rhode Island |

(a) New York's legislature deadlocked, so no electors were chosen.

(b) One electoral district failed to choose an elector.

See also

References

- ↑ "National General Election VEP Turnout Rates, 1789-Present". United States Election Project. CQ Press.

- ↑ Meacham 2012

- ↑ Chernow, 272-273

- ↑ "VP George Clinton". www.senate.gov. Retrieved 2016-04-15.

- 1 2 United States presidential election of 1789 at Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ "A New Nation Votes".

- ↑ "1789 Presidential Electoral Vote Count". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Dave Leip. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ↑ "The Electoral Count for the Presidential Election of 1789". The Papers of George Washington. Archived from the original on September 14, 2013. Retrieved May 4, 2005.

Bibliography

- Bowling, Kenneth R., and Donald R. Kennon. "A New Matrix for National Politics." Inventing Congress: Origins and Establishment of the First Federal Congress. Athens, O.: United States Capitol Historical Society by Ohio U, 1999. 110-37. Print.

- Chernow, Ron (2004). "Alexander Hamilton". London, UK: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-1101200858.

- Collier, Christopher. "Voting and American Democracy." The American People as Christian White Men of Property:Suffrage and Elections in Colonial and Early National America. N.p.: U of Connecticut, n.d, 1999.

- DenBoer, Gordon, ed. (1990). The Documentary History of the First Federal Elections, 1788–1790. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-06690-1.

- Dinkin, Robert J. Voting in Revolutionary America: A Study of Elections in the Original Thirteen States, 1776–1789. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1982.

- Ellis, Richard J. (1999). Founding the American Presidency. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8476-9499-0.

- McCullough, David (1990). John Adams. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-7588-7.

- Meacham, Jon (2012). Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6766-4.

- Novotny, Patrick. The Parties in American Politics, 1789–2016.

- Paullin, Charles O. "The First Elections Under The Constitution." The Iowa Journal of History and Politics 2 (1904): 3-33. Web. February 20, 2017.

- Shade, William G., and Ballard C. Campbell. "The Election of 1788-89." American Presidential Campaigns and Elections. Ed. Craig R. Coenen. Vol. 1. Armonk, NY: Sharpe Reference, 2003. 65-77. Print.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to United States presidential election, 1788–89. |

- United States presidential election of 1789 at Encyclopædia Britannica

- Presidential Election of 1789: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns, 1787–1825

- "A Historical Analysis of the Electoral College". The Green Papers. Retrieved February 17, 2005.

- Election of 1789 in Counting the Votes

.jpg)

.jpg)