Inside Llewyn Davis

| Inside Llewyn Davis | |

|---|---|

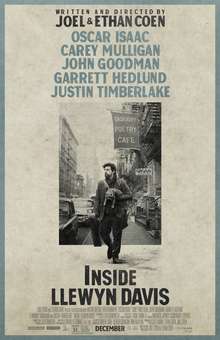

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | |

| Produced by |

|

| Written by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Bruno Delbonnel |

| Edited by |

|

Production company | |

| Distributed by | CBS Films |

Release date |

|

Running time | 105 minutes |

| Country |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $11 million[2] |

| Box office | $32.9 million[3] |

Inside Llewyn Davis (/ˈluːɪn/) is a 2013 French-American black comedy tragedy[4][5][6][7] film written, directed, produced, and edited by Joel and Ethan Coen. Set in 1961, the film follows one week in the life of Llewyn Davis, played by Oscar Isaac in his breakthrough role, a folk singer struggling to achieve musical success while keeping his life in order. It co-stars Carey Mulligan, John Goodman, Garrett Hedlund, F. Murray Abraham, and Justin Timberlake.

Although Davis is a fictional character, the story was partly inspired by the autobiography of folk singer Dave Van Ronk.[8] Most of the folk songs performed in the film are sung in full and recorded live. T Bone Burnett was the executive music producer.

The film won the Grand Prix at the 2013 Cannes Film Festival, where it screened on May 19, 2013. The film began a limited release in the United States on December 6, 2013, and a wide release on January 10, 2014. The film received critical acclaim and was nominated for two Academy Awards (Best Cinematography and Best Sound Mixing) and three Golden Globe Awards: Best Motion Picture – Comedy or Musical, Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy (Oscar Isaac), and Best Original Song.

Inside Llewyn Davis has been highly acclaimed, and was voted the 11th best film released since 2000 by film critics in a 2016 BBC Culture poll.[9] It was also chosen the eleventh "Best Film of the 21st Century So Far" in 2017 by The New York Times.[10]

Plot

In February 1961, Llewyn Davis is a struggling folk singer in New York City's Greenwich Village. His recent solo album Inside Llewyn Davis is not selling; he has no money and is sleeping on the couches of friends and acquaintances. He plays The Gaslight Cafe one night, then gets punched out in the alley.

Llewyn wakes up in the apartment of two friends, the Gorfeins. When he leaves, the Gorfeins' cat escapes and Llewyn is locked out. Llewyn takes the cat to the apartment of Jim and Jean Berkey. Jean reluctantly agrees to let Llewyn stay that night. Jean tells Llewyn she is pregnant, with a possibility it is Llewyn's child. The next morning, the Gorfeins' cat escapes again. Later, Jean asks Llewyn to pay for an abortion, though she is upset she just might be losing Jim's child.

Llewyn visits his sister hoping to borrow money; instead, she gives him a box of his belongings, but he tells her to trash it. She mentions that he could make money by going back to the Merchant Marine. On Jim's invitation, Llewyn records a space travel-themed novelty song with Jim and Al Cody. Needing money for the abortion, Llewyn agrees to an immediate $200 rather than royalties. Llewyn is setting up Jean's appointment when the gynecologist informs him there is no charge, as a previous girlfriend did not go through with the abortion Llewyn had paid for.

While talking to Jean at a café, Llewyn spots what he believes to be the Gorfeins' cat and returns it that evening. Asked to play after dinner, he reluctantly performs "Fare Thee Well", a song he had recorded with Mike. When Mrs. Gorfein starts to sing Mike's harmony, Llewyn becomes angry and yells at her. Mrs. Gorfein leaves the table crying, then returns with the cat, having realized that it is not theirs. Llewyn leaves with the cat.

Llewyn rides with two musicians driving to Chicago: the laconic beat poet Johnny Five and the odious jazz musician Roland Turner. During the trip Llewyn discloses that his musical partner, Mike Timlin, died by suicide.

At a roadside restaurant, Roland collapses from a heroin overdose. The three stop on the side of the highway to rest. When a police officer tells them to move on, he suspects that Johnny is drunk and tells him to get out of the car. Johnny resists and is arrested. Without the keys, Llewyn abandons the car, leaving the cat and the unconscious Roland behind. In Chicago, Llewyn auditions for Bud Grossman, who says Llewyn is not suited to be a solo performer but suggests he might incorporate him in a new trio he is forming. Llewyn rejects the offer and hitchhikes back to New York. Driving, he hits what he fears may be the same cat.

Back in New York, Llewyn uses his last $148 for back dues to rejoin the Merchant Marine union, and visits his ailing father. He searches for his seaman's license so he can ship out with the Merchant Marine, but it was in the box his sister finally trashed. Llewyn goes back to the Union Hall to replace it, but he cannot afford the $85 fee. He visits Jean and she tells him she got him a gig at the Gaslight.

At the Gaslight, Llewyn learns that Pappi, the manager, also had sex with Jean. Llewyn, angered by this, heckles a woman as she performs, and is thrown out. He then goes to the Gorfeins' apartment, where they graciously welcome him. There, he learns that the novelty song is likely to be a major hit, with massive royalties. He is amazed to see that their actual cat, Ulysses, has found his way home.

Returning to an expanded version of the film's opening scene, Llewyn performs at the Gaslight. Pappi teases Llewyn about his heckling the previous evening and tells him that a friend of his is waiting in the alley. As he leaves, Llewyn watches a young Bob Dylan perform. Behind the Gaslight, Llewyn is beaten by a shadowy suited man for heckling his wife, the previous night's performer. Llewyn watches as the man leaves in a taxi and he bids him "Au revoir".

Cast

- Oscar Isaac as Llewyn Davis

- Carey Mulligan as Jean Berkey

- John Goodman as Roland Turner

- Justin Timberlake as Jim Berkey

- Adam Driver as Al Cody

- F. Murray Abraham as Bud Grossman

- Garrett Hedlund as Johnny Five

- Stark Sands as Troy Nelson

- Ethan Phillips as Mitch Gorfein

- Robin Bartlett as Lillian Gorfein

- Alex Karpovsky as Marty Green

- Max Casella as Pappi Corsicato

- Frank L. Ridley as Union Hall Man

Production

Set in 1961, Inside Llewyn Davis was inspired by the cultural disconnection within a New York–based music scene, where the songs seemed to come from all parts of the United States except New York, but whose performers included Brooklyn-born Dave Van Ronk and Ramblin' Jack Elliott. Well before writing the script, the Coens began with a single idea, of Van Ronk being beaten up outside of Gerde's Folk City in the Village. The filmmakers employed the image in the opening scenes, then periodically returned to the project over the next couple of years to expand the story using a fictional character.[11] One source for the film was Van Ronk's posthumously published (2005) memoir, The Mayor of MacDougal Street. According to the book's co-author, Elijah Wald, the Coens mined the work "for local color and a few scenes".[12][13][14] The character is a composite of Van Ronk, Elliot, and other performers from the New York boroughs who performed in the Village at that time.[11] Joel Coen remarked that "the film doesn't really have a plot. That concerned us at one point; that's why we threw the cat in."[15]

Shooting was complicated by an early New York spring, which interfered with the bleak winter atmosphere that prevails throughout the film,[16] and by the difficulty of filming several cats, who, unlike dogs, ignore the desires of filmmakers. On the advice of an animal trainer, the Coens put out a casting call for an orange tabby cat, which is sufficiently common that several cats would be available to play one part. Individual cats were then selected for each scene based on what they were predisposed to do on their own.[11]

Producer Scott Rudin, who worked with the Coens on No Country for Old Men and True Grit, collaborated on the project. StudioCanal helped finance it without an American distributor in place. "After shooting in New York City and elsewhere last year ... the brothers finished the movie at their own pace", wrote Michael Cieply in a January 2013 New York Times interview with Joel Coen ahead of a private, pre-Grammys screening in Los Angeles. "They could have rushed it into the Oscar season but didn't."[13] On February 19, CBS Films announced it had picked up the U.S. domestic distribution rights for about $4 million. StudioCanal has rights to international distribution and foreign sales.[17][18]

Music

Dave Van Ronk's music served as a starting point for the Coens as they wrote the script, and many of the songs first designated for the film were those he had recorded. Van Ronk biographer Elijah Wald said that the character of Llewyn Davis "is not at all Dave, but the music is".[19] (The cover of Davis's solo album, Inside Llewyn Davis, resembles that of Inside Dave Van Ronk. Both feature the artist in a doorway, wearing a tweed jacket and smoking a cigarette.[20] One difference between the two covers is that there is a cat in the doorway on the cover of Inside Dave Van Ronk. Other songs emerged in conversations between the Coens and T Bone Burnett, who produced the music in association with Marcus Mumford.[13][16][21] Burnett had previously worked with the Coens on the music and soundtrack for The Big Lebowski and O Brother, Where Art Thou?, the latter of which sold about 8 million copies in the United States.[22] The Coens viewed the music in Inside Llewyn Davis as a direct descendant of the music in O Brother.[11]

The humorous novelty song "Please Mr. Kennedy", a plea from a reluctant astronaut, appears to be a fourth generation derivative of the 1960 song "Mr. Custer", also known as "Please Mr. Custer", about the Battle of the Little Bighorn, sung by Larry Verne and written by Al De Lory, Fred Darian, and Joseph Van Winkle. A Tamla-Motown single followed in 1961: "Please Mr. Kennedy (I Don't Want to Go)", a plea from a reluctant Vietnam War draftee, sung by Mickey Woods and credited to Berry Gordy, Loucye Wakefield and Ronald Wakefield. In 1962 using a similar theme, The Goldcoast Singers recorded "Please Mr. Kennedy" on its Here They Are album, with writing credits to Ed Rush and George Cromarty. The Llewyn Davis version credits Rush, Cromarty, Burnett, Timberlake, and the Coens.[11][23][24]

Isaac, Timberlake, Mulligan, Driver and others performed the music live.[25][26] The exception was "The Auld Triangle", which was lip-synced, with Timberlake singing bass. (Timberlake's vocal range was on display in the film. Critic Janet Maslin, listening to a soundtrack recording, confused Timberlake's voice with Mulligan's, which she thought resembled that of Mary Travers.)[11]

Release

Inside Llewyn Davis had its worldwide premiere on May 19 at the 2013 Cannes Film Festival.[27][28] The film then screened at other film festivals, including the New York Film Festival in September, the AFI Film Festival, on its November 14 close, and the Torino Film Festival, also in November.[29][30]

The film began a limited release in the United States on December 6, 2013, where it played in Los Angeles and New York. It opened in 133 additional theaters on December 20 and wide on January 10, 2014.[31][32]

It was released on DVD and Blu-ray in the US on March 11, 2014. On January 19, 2016, The Criterion Collection released a DVD and Blu-ray of the film, featuring new audio commentary tracks, interviews and other special features, including a forty-three-minute documentary titled Inside "Inside Llewyn Davis".[33]

Reception

Critical response

Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a rating of 93%, based on 260 reviews, with an average score of 8.5/10. The website's critical consensus states: "Smart, funny, and profoundly melancholy, Inside Llewyn Davis finds the Coen brothers in fine form."[34] Metacritic gives the film a score of 93 out of 100, based on reviews from 52 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[35] It was voted the 11th greatest film of the 21st century in a 2016 BBC Culture poll, after No Country for Old Men, another film by the Coen brothers.[9]

Writing for The Village Voice, Alan Scherstuhl praised the Coen brothers' film: "While often funny and alive with winning performances, Inside Llewyn Davis finds the brothers in a dark mood, exploring the near-inevitable disappointment that faces artists too sincere to compromise—disappointments that the Coens, to their credit, have made a career out of dodging. The result is their most affecting film since the masterful A Serious Man."[36] Todd McCarthy of The Hollywood Reporter called the film "an outstanding fictional take on the early 1960s folk music scene", praising the "fresh, resonant folk soundtrack", and Oscar Isaac's performance, that "deftly manages the task of making Llewyn compulsively watchable".[37] IGN reviewer Leigh Singer gave the film a 10 out of 10 'Masterpiece' score, saying "Don't be fooled by the seemingly minor key ... this is one of the finest works by – let’s just call it – the most consistently innovative, versatile and thrilling American filmmakers of the last quarter-century."[38]

Folk singers, however, have criticized the film for misrepresenting the friendliness of the Village folk scene of the time. Terri Thal, Dave Van Ronk's ex-wife, said, "I didn't expect it to be almost unrecognizable as the folk-music world of the early 1960s."[39] Suzanne Vega said, "I feel they took a vibrant, crackling, competitive, romantic, communal, crazy, drunken, brawling scene and crumpled it into a slow brown sad movie."[40] The film was also criticized for the fact that, although it was to some extent based on the memoir of Dave Van Ronk, the film portrayed a character very much at odds with the real Van Ronk, usually described as a "nice guy".[40][41] However, at a press interview before the film premiered at Cannes, the Coens stated that the character itself was an original creation, and that the music was the major influence they had drawn from Van Ronk.[42]

Accolades

References

- ↑ "Inside Llewyn Davis (2012)". British Film Institute. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ↑ Michael Phillips (October 24, 2013). "When movies make the most of their budgets, it shows". Chicago Tribune. Tribune Company. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- ↑ "Inside Llewyn Davis (2013)". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Retrieved March 13, 2014.

- ↑ Nicholson, Amy (January 2, 2014). "Oscar Isaac on the "screwball tragedy" of Inside Llewyn Davis".

- ↑ Morris, Wesley (December 6, 2013). "Now Playing: Bad Luck, Tragedy, and Travesty".

- ↑ Varga, George (December 19, 2013). "'Inside Llewyn Davis' witty, bleak, superb". San Diego Union Tribune. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- ↑ Puig, Claudia (December 4, 2013). "Enigmatic 'Llewyn Davis' is worth puzzling over". USA Today. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- ↑ Wald, Elija. "Before the Flood: LLewyn Davis, David Van Ronk, and the Village Folk Scene of 1981". Inside Llewyn Davis (official site). Archived from the original on February 9, 2014. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- 1 2 "The 21st Century's 100 greatest films". bbc.com. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ↑ Dargis, Manohla; Scott, A.O. "The 25 Best Films of the 21st Century...So Far". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "The Coen Bros. On Writing, Lebowski And Literally Herding Cats". Fresh Air transcript. National Public Radio. December 17, 2013.

- ↑ Wald, Elija. "The World of Llewyn Davis". Inside Llewyn Davis official site. CBS Films. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Cieply, Michael (January 27, 2013). "Macdougal Street Homesick Blues". The New York Times. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ↑ Russ Fischer (June 25, 2011). "The Coen Bros. New Script is Based on the 60′s NYC Folk Scene". /Film. Retrieved February 11, 2012.

- ↑ "The New Superstar at Cannes: A Ginger Tom Cat". The Telegraph. Retrieved October 11, 2013.

- 1 2 "NYFF51: Inside Llewyn Davis Press Conference". YouTube. September 29, 2013.

- ↑ "CBS Films Pays $4 Million for Coen Bros.' Inside Llewyn Davis". Billboard. The Hollywood Reporter. February 19, 2013. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ↑ "CBS Films Acquires The Coen Brothers' Inside Llewyn Davis" (Press release). CBS Films. February 19, 2013. Archived from the original on February 23, 2013. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ↑ Haglund, David. "The People Who Inspired Inside Llewyn Davis". Slate. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ↑ Golden, Zara (December 5, 2013). "What's Real in Inside Llewyn Davis: Llewyn Davis' Album Cover Looks Very Familiar". Rolling Stone.

- ↑ Associated Press (May 19, 2013). "Coens' folk revival 'Llewyn' serenades Cannes". The Oklahoman.

- ↑ Jurgensen, John (November 21, 2013). "T Bone Burnett and the Coen Brothers Move the Music Needle". Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ Myers, Mitch (December 3, 2013). "Inside Llewyn Davis: From General Custer to Mr. Kennedy, the Genesis of a Novelty Song". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ↑ "Inside Llewyn Davis". Nonesuch (track listing).

- ↑ Christgau, Robert (December 4, 2013). "The Lost World of Llewyn Davis: Christgau on the Coen Brothers". Rolling Stone.

- ↑ "Inside Llewyn Davis with Production Mixer Peter F. Kurkland". Sound & Picture. February 3, 2014.

- ↑ "2013 Official Selection". Cannes. April 18, 2013. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ↑ Knegt, Peter (May 9, 2013). "Here's The Screening Schedule For The 2013 Cannes Competition Lineup". The Playlist. Indiewire. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

- ↑ "Inside Llewlyin Davis (program description)". The 51st New York Film Festival. Film Society of Lincoln Center.

- ↑ Friedlander, Whitney (November 15, 2013). "Inside Llewyn Davis Star Oscar Isaac Compares Coens to Chekhov at AFI Fest Closing". Variety.

- ↑ McNary, Dave (May 3, 2013). "Coen Brothers' Inside Llewyn Davis Dated For Dec. 6". Variety. Reed Business Information. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- ↑ Brooks, Brian (December 22, 2013). "Specialty Box Office: Her Nabs $42K Per-Screen; Bollywood's Dhoom 3 Sizzles; The Past Coasts In Opening; Llewyn Davis Still Faring Well". Deadline Hollywood.

- ↑ "Inside Llewyn Davis (2013)". Criterion. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- ↑ "Inside Llewyn Davis (2013)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ↑ "Inside Llewyn Davis Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ↑ "Inside Llewyn Davis: The Coen Brothers' Most Moving Film Since A Serious Man". The Village Voice. September 27, 2013. Retrieved September 27, 2013.

- ↑ McCarthy, Todd (May 18, 2013). "Inside Llewyn Davis: Cannes Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- ↑ Leigh Singer (May 21, 2013). "Inside Llewyn Davis Review". IGN. Retrieved February 13, 2016.

- ↑ Terri Thal (December 13, 2013). "Dave Van Ronk's Ex-Wife Takes Us Inside Inside Llewyn Davis". Village Voice. Archived from the original on February 25, 2015. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- 1 2 Aimee Levitt (January 17, 2014). "The folk-song army's attack on Inside Llewyn Davis". Chicago Reader. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- ↑ David Browne (December 2, 2014). "Meet the Folk Singer Who Inspired Inside Llewyn Davis". Rolling Stone. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- ↑ "Interview of Inside Llewyn Davis by Ethan Coen, Joel Coen". Cannes Film Festival. May 19, 2013. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Inside Llewyn Davis |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Inside Llewyn Davis. |