Taos Pueblo

| Taos Pueblo Pueblo de Taos tə̂otho or tə̂obo ȉałopháymųp’ȍhə́othə̀olbo or ȉałopháybo | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Location | Near Taos, Taos County, New Mexico, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 36°26′21″N 105°32′44″W / 36.43917°N 105.54559°WCoordinates: 36°26′21″N 105°32′44″W / 36.43917°N 105.54559°W |

| Governing body | Native American tribal government |

| Official name: Pueblo de Taos | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iv |

| Designated | 1992 (16th session) |

| Reference no. | 492 |

| State Party | USA |

| Region | Europe and North America |

| Designated | October 15, 1966 |

| Reference no. | 66000496[1] |

| Area | 19 acres (7.7 ha) |

| Architecture | Pueblo |

| Designated | October 9, 1960[2] |

| Designated | March 13, 1972 |

| Reference no. | 243 |

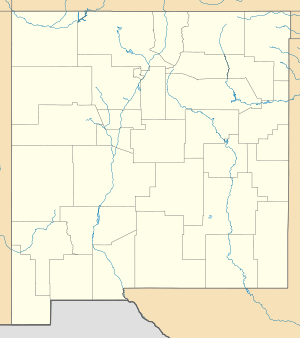

Location within New Mexico  Taos Pueblo (the US) | |

| t’óynemą | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| 4,500 (2010 U.S. Census) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

| |

| Languages | |

| Taos (Tiwa), English, Spanish | |

| Religion | |

| Taos religion (Pueblo religion), Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Tanoan peoples |

Taos Pueblo (or Pueblo de Taos) is an ancient pueblo belonging to a Taos-speaking (Tiwa) Native American tribe of Puebloan people. It lies about 1 mile (1.6 km) north of the modern city of Taos, New Mexico. The pueblos are considered to be one of the oldest continuously inhabited communities in the United States.[3] This has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Taos Pueblo is a member of the Eight Northern Pueblos, whose people speak two variants of the Tanoan language. The Taos community is known for being one of the most private, secretive, and conservative pueblos. Natives will almost never speak of their religious customs to outsiders, and because their language has never been written down, much of the culture remains unknown to the rest of the world. A reservation of 95,000 acres (38,000 ha) is attached to the pueblo, and about 4,500 people live in this area.[4]

Setting

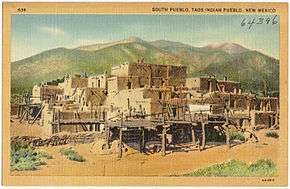

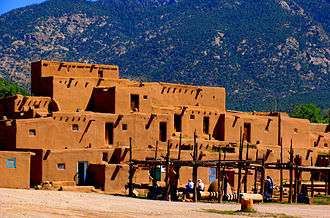

The pueblo was constructed in a setting backed by the Taos Mountains of the Sangre de Cristo Range. The settlement was built on either side of Rio Pueblo de Taos, also called Rio Pueblo and Red Willow Creek, a small stream that flows through the middle of the pueblo compound. Its headwaters come from the nearby mountains.

Taos Pueblo's most prominent architectural feature is a multi-storied residential complex of reddish-brown adobe, built on either side of the Rio Pueblo. The Pueblo's website states it was probably built between 1000 and 1450.[4]

The pueblo was designated a National Historic Landmark on October 9, 1960. In 1992 it was designated as a UNESCO Heritage Site. As of 2006, about 150 people live in the historic complex full-time.[4]

Name

Taos language

In the Tanoan language of Taos (Northern Tiwa), the pueblo is referred to as "the village" in either tə̂otho "in the village" (tə̂o- "village" + -tho "in") or tə̂obo "to/toward the village" (tə̂o- "village" + -bo "to, toward"). The proper name of the pueblo is ȉałopháymųp’ȍhə́othə̀olbo "at red willow canyon mouth" (or ȉałopháybo "at the red willows" for short).[5] This name is more commonly used in ceremonial contexts and is less common in everyday speech.

Spanish language

The name Taos in English was borrowed from Spanish Taos. Spanish Taos is probably a borrowing of Taos tə̂o- "village" which was heard as tao to which the plural -s was added although in the modern language Taos is no longer a plural noun. The idea that the Spanish Taos is from tao, "cross of the order of San Juan de los Caballeros" (from Greek tau), is unlikely.[6]

History

Pre-Columbian

Most archeologists believe that the Taos Indians, along with other Pueblo Indians, settled along the Rio Grande after migrating south from the Four Corners region.[7] The dwellings of that region were inhabited by the Ancestral Puebloans. A long drought in the area in the late 13th century may have caused them to move to the Rio Grande, where the water supply was more dependable. However, their reason for migrating is still disputed and there is evidence that a violent struggle took place. Ultimately, archeological clues point to the idea that the Natives may have been forced to leave.

Throughout its early years, Taos Pueblo was a central point of trade between the native populations along the Rio Grande and their Plains Tribes neighbors to the northeast. Taos Pueblo hosted a trade fair each fall after the agricultural harvest.[8]

Post-contact

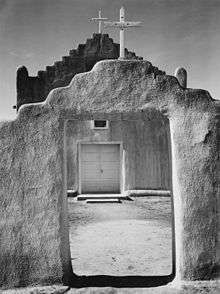

The first Spanish visitors to Taos Pueblo arrived in 1540; they were members of the Francisco Vásquez de Coronado expedition, which stopped at many of New Mexico's pueblos in search of the rumored Seven Cities of Gold. Around 1620, Spanish Jesuits oversaw construction of the first Catholic Church in the pueblo, the mission of San Geronimo de Taos. Reports from the period indicate that the native people of Taos resisted the building of the church and imposition of the Catholic religion. Throughout the 1600s, cultural tensions grew between the native populations of the Southwest and the increasing Spanish colonial presence. Taos Pueblo was no exception. By 1660, the native people killed the resident priest and destroyed the church. Several years after it was rebuilt, the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 began; the Taos destroyed the church and killed two resident priests.[8]

By the turn of the 18th century, San Geronimo de Taos was under construction for a third time. Spanish/Taos relations within the pueblo became amicable for a brief period as both groups found a common enemy in invading Ute and Comanche tribes. Resistance to Catholicism and Spanish culture was still strong. Even so, Spanish religious ideals and agricultural practices subtly worked their way into the Taos community, largely starting during this time of increased cooperation between the two cultural groups.[8]

The Taos revolt began before the conclusion of the Mexican–American War in 1847. A Mexican Pablo Montoya and Tomasito, a leader at Taos Pueblo, led a force of Mexicans and Taos who did not want to become a part of the United States. They killed Governor Charles Bent and others and marched on Santa Fe. The revolt was suppressed after the rebels took refuge in San Geronimo Mission Church. The American troops bombarded the church, killing or capturing the insurrectionists and destroying the physical structure. Around 1850, a new mission church was constructed near the west gate of the pueblo wall. The ruins of the original church and its 1850s replacement are both still visible inside the pueblo wall today.[8] Father Anton Docher first served as a priest in Taos before his years in Isleta, where he became known as "The Padre of Isleta".[9]

In 1924-25 the Taos Pueblo culture was studied by German psychiatrist Carl Jung, who visited the Pueblo led by Ochwiay Biano. He was very interested in indigenous societies as he believed they were more closely in touch with archetypes.

Taos Mountain

The Pueblo's 48,000 acres (19,000 ha) of mountain land was taken by President Theodore Roosevelt and designated as the Carson National Forest early in the 20th century. It was finally returned in 1970 by the United States when President Nixon signed Public Law 91-550.[10] An additional 764 acres (309 ha) south of the ridge between Simpson Peak and Old Mike Peak and west of Blue Lake were transferred back to the Pueblo in 1996.[11]

Blue Lake

Blue Lake, which the people of the Pueblo consider sacred, was included in this return of Taos land. The Pueblo notably involved non-native people in lobbying the federal government for the return of Blue Lake, as they argued that their unrestricted access to the lake and the surrounding region was necessary to ensure their religious freedom.[12] The Pueblo's web site names the reacquisition of the sacred Blue Lake as the most important event in its history due to the spiritual belief that the Taos people originated from the lake.[13] It is believed that their ancestors live there, and the pueblos themselves only ascend the mountain twice a year.

Architecture

At the time of the Spaniards' initial contact, Hernando de Alvarado described the pueblo as having adobe houses built very close together and stacked five or six stories high. The homes became narrower as they rose, with the roofs of each level providing the floors and terraces for those above.[8]

The buildings at Taos originally had few windows and no standard doorways. Instead, access to rooms was through square holes in the roof that the people reached by climbing long, wooden ladders. Engelmann Spruce logs (or vigas) supported roofs that had layers of branches, grass, mud, and plaster covering them. The architecture and the building materials were well suited for the rigors of the environment and the needs of the people in the Taos Valley.[8] It should be noted that prior to the arrive of Coronado, all Taos Pueblo walls were constructed using balls of adobe ( clay ) about the size of a 'soft ball', Coronado introduced the technique of the formed mud brick, this technique revolutionized adobe construction in the new world. Coronado also changed the roof structure, to use 2" to 4" inch aspen saplings branches installed at a right angle to the Engelmann Spruce vigas, then 2" to 3" inches of adobe plaster was applied, topped off with up to half a meter of loose soil ( about 18" inches thick ) for insulation and structural strength. Thus indigenous architecture evolved.

The first Spanish-influenced architecture appeared in Taos Pueblo after Fray Francisco de Zamora came there in 1598 to establish a mission, under orders from Spanish Governor, Don Juan de Oñate.[8]

Main structure

The north-side Pueblo is said to be one of the most photographed and painted buildings in North America.[14] It is the largest multistoried Pueblo structure still existing. It is made of adobe walls that are often several feet thick. Its primary purpose was for defense.[7] Up to as late as 1900, access to the rooms on lower floors was by ladders on the outside to the roof, and then down an inside ladder. In case of an attack, outside ladders could easily be pulled up.

Homes

The homes in this structure usually consist of two rooms, one of which is for general living and sleeping, and the second of which is for cooking, eating, and storage. Each home is self-contained; there are no passageways between the houses. Taos Indians made little use of furniture in the past, but today they have tables, chairs, and beds. In the pueblo, electricity, running water, and indoor plumbing are prohibited.[7]

Spiritual community

.%22_New_Mexico%2C_1933_-_1942_-_NARA_-_519986.jpg)

Religious practices

Two spiritual practices are represented in the Pueblo: the original indigenous spiritual and religious tradition[4] and Roman Catholicism. The majority of Taos Indians practice their still-vital, ancient indigenous religion.[7] Most (90%) members of the Taos Pueblo community are baptized as Roman Catholics.[4] Saint Jerome, or San Geronimo, is the patron saint of the pueblo.[15]

In culture

- Author and poet Nancy Wood was greatly influenced by her time spent at Taos Pueblo, and it is featured in much of her work.[16]

See also

Notes

- ↑ National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "National Historic Landmarks Survey, New Mexico" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- ↑ "Taos Pueblo", Taos website

- 1 2 3 4 5 "About Taos Pueblo". Taos Pueblo. 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

- ↑ Sturtevant, William C. (1978). Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 9: Southwest. Government Printing Office. p. 267. ISBN 9780160045776. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ↑ Jones, William. (1960). "Origin of the place name Taos", Anthropological Linguistics, 2 (3), 2–4; Trager, George L. (1960). "The name of Taos, New Mexico", Anthropological Linguistics, 2 (3), 5–6.

- 1 2 3 4 "Pueblo de Taos". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Taos Pueblo". National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- ↑ Leo Crane. Desert Drums: The Pueblo Indians of New Mexico, 1540–1928. Rio Grande Press, 1972.

- ↑ Julyan, B: New Mexico's Wilderness Areas: The Complete Guide, page 73. Big Earth Publishing, 1999

- ↑ "Public Law 104-333" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 31, 2008. Retrieved July 19, 2008.

- ↑ Bodine, John J. (1973). "Blue Lake: A Struggle for Indian Rights". American Indian Law Review. JSTOR 20067803.

- ↑ Keegan, Marcia (2010). Taos Pueblo and Its Sacred Blue Lake: Reflections on the Fortieth Anniversary from Members of Taos Pueblo. Clear Light Pub. ISBN 9781574160994.

- ↑ Rodríguez, Sylvia (2009-04-10). The Matachines Dance: A Ritual Dance of the Indian Pueblos and Mexicano/Hispano Communities. Sunstone Press. p. 17. ISBN 9780865346345. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ↑ Scott, Sascha T. (2008). Paintings of Pueblo Indians and the Politics of Preservation in the American Southwest. ProQuest. p. 25. ISBN 9780549890423. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ↑ Sharpe, Tom (March 13, 2013). "Nancy Wood, 1936-2013: Writer, photographer found new 'way of being and seeing' in New Mexico". Santa Fe New Mexican. Retrieved October 9, 2016.

References

- Bodine, John J (1996). Taos Pueblo: A Walk Through Time. Tucson: Rio Nuevo Publishers. ISBN 9781887896955.

![]()

Further reading

- Wenger, Tisa Joy (2009). We Have a Religion: The 1920s Pueblo Indian Dance Controversy and American Religious Freedom. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807832622.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Taos Pueblo (community). |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pueblo de Taos (historic pueblo). |

- Official website

- Indianpueblo.org—Indian Pueblo Cultural Center: Taos Pueblo

- unesco.org: Taos Pueblo — UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- Sacredland.org: Taos Blue Lake

- Princeton.edu: Taos Blue Lake Collection — at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton University.

- National Park Service—NPS: Taos Pueblo — on NPS "Discover Our Shared Heritage" website.

- SMU-in-Taos: Research Publications digital collection — SMU-in-Taos (Fort Burgwin) campus; anthropological + archaeological monographs + edited volumes.