Ansel Adams

| Ansel Adams | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Ansel Easton Adams February 20, 1902 San Francisco, California, US |

| Died |

April 22, 1984 (aged 82) Monterey, California |

| Known for | Photography and conservationism |

| Spouse(s) | Virginia Rose Best |

| Website |

anseladams anseladams |

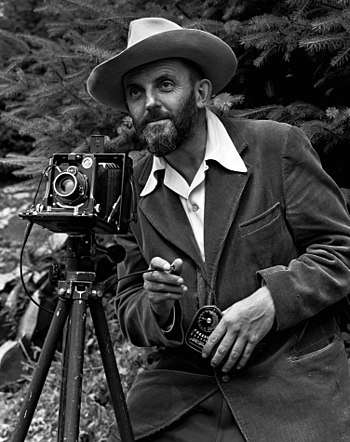

Ansel Easton Adams (February 20, 1902 – April 22, 1984) was an American landscape photographer and environmentalist. His black-and-white images of the American West, especially Yosemite National Park, have been widely reproduced on calendars, posters, books, and the internet.[1]

Adams and Fred Archer developed the Zone System as a way to determine proper exposure and adjust the contrast of the final print. The resulting clarity and depth characterized his photographs. He primarily used large-format cameras because the large film used with these cameras (primarily 5×4 and 8×10) contributed to the clarity of his prints.

Adams initiated the photography group known as Group f/64, along with fellow photographers Willard Van Dyke and Edward Weston.

Biography

Early life

Childhood

Adams was born in the Western Addition of San Francisco, California, the only child of Charles Hitchcock Adams and Olive Bray Adams. He was named after his uncle, Ansel Easton. His mother's family came from Baltimore, where his maternal grandfather had a successful freight-hauling business but lost his wealth investing in failed mining and real estate ventures in Nevada.[2] The Adams family came from New England, having migrated from Northern Ireland during the early 18th century. His paternal grandfather founded and built a prosperous lumber business which his father later managed. Later in life, Adams condemned the industry for cutting down many of the great redwood forests.[3]

One of Adams's earliest memories was watching the smoke from the fires caused by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. Then four years old, Adams was uninjured in the initial shaking but was tossed face-first into a garden wall during an aftershock three hours later, breaking and scarring his nose. A doctor recommended that his nose be reset once he reached maturity,[4] but it remained crooked for his entire life.[5]

In 1907, his family moved 2 miles (3 km) west to a new home near the Seacliff neighbourhood, just south of the Presidio Army Base.[6] The home had a "splendid view" of the Golden Gate and the Marin Headlands.[7]

Adams was a hyperactive child and prone to frequent sickness and hypochondria. He had few friends, but his family home and surroundings on the heights facing the Golden Gate provided ample childhood activities. He had little patience for games or sports, but enjoyed the beauty of nature from an early age, collecting bugs and exploring Lobos Creek all the way to Baker Beach and the sea cliffs leading to Lands End,[7][8] "San Francisco's wildest and rockiest coast, a place strewn with shipwrecks and rife with landslides."[9]

His father bought a three-inch telescope, and they enthusiastically shared the hobby of amateur astronomy, visiting the Lick Observatory on Mount Hamilton together. His father later served as the paid secretary-treasurer of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific from 1925 to 1950.[10]

Ansel's father's business suffered great financial losses after the death of Ansel's grandfather and the aftermath of the Panic of 1907. Some of the induced near-poverty was because Ansel's uncle Ansel Easton and Cedric Wright's father George Wright had secretly sold their shares of the company to the Hawaiian Sugar Trust for a large amount of money, "knowingly providing the controlling interest."[11] By 1912, the family's standard of living had dropped sharply.[12]

Ansel was dismissed from several private schools for being restless and inattentive, so his father decided to remove him from school in 1915 at age 12. Adams was then educated by private tutors, his aunt Mary, and by his father. His aunt Mary was a devotee of Robert G. Ingersoll, a 19th-century agnostic and women's suffrage advocate. As a result of his aunt's influence, Ingersoll's teachings were important to Ansel's upbringing.[13] During the Panama–Pacific International Exposition in 1915, his father insisted that Adams spend part of each day studying the exhibits as part of his education.[14] Adams eventually resumed and then completed his formal education by attending the Mrs. Kate M. Wilkins Private School, graduating from eighth grade on June 8, 1917. During his later years, he displayed his diploma in the guest bathroom of his home.[15]

His father raised him to follow the ideas of Ralph Waldo Emerson: to live a modest, moral life guided by a social responsibility to man and to nature.[13] Adams had a loving relationship with his father, but he had a distant relationship with his mother, who did not approve of his interest in photography.[16] The day after her death in 1950, Ansel had a dispute with the undertaker when choosing the casket in which to bury her. He chose the cheapest in the room, a $260 casket that seemed the least he could purchase without doing the job himself. The undertaker remarked, "Have you no respect for the dead?" Adams replied, "One more crack like that and I will take Mama elsewhere."[17]

Youth

Adams became interested in piano at age 12, and music became the main focus of his later youth. His father sent him to piano teacher Marie Butler, who emphasized perfectionism and accuracy. After four years of studying with her, he had other teachers, one being composer Henry Cowell.[18] For the next twelve years, the piano was Adams's primary occupation and by 1920, his intended profession.

Adams first visited Yosemite National Park in 1916 with his family.[19] He wrote of his first view of the valley: "the splendor of Yosemite burst upon us and it was glorious.... One wonder after another descended upon us.... There was light everywhere.... A new era began for me." His father gave him his first camera during that stay, a Kodak Brownie box camera, and he took his first photographs with his "usual hyperactive enthusiasm".[20] He returned to Yosemite on his own the next year with better cameras and a tripod. During the winter, he learned basic darkroom technique while working part-time for a San Francisco photograph finisher.[21]

Adams contracted the Spanish Flu during the 1918 flu pandemic and became seriously ill, but he recovered after several months to resume his outdoor life.

Adams avidly read photography magazines, attended camera club meetings, and went to photography and art exhibits. He explored the High Sierra during summer and winter with retired geologist and amateur ornithologist Francis Holman, whom he called "Uncle Frank". During this time, he developed the stamina and skill needed to photograph at high elevation and with difficult weather conditions.[22]

While in Yosemite, he had frequent contact with the Best family, owners of Best's Studio, who allowed him to practice on their old square piano. In 1928, he married Virginia Best in Best's Studio in Yosemite Valley. Virginia inherited the studio from her artist father on his death in 1935, and the Adams continued to operate it until 1971. The studio is now known as the Ansel Adams Gallery and remains owned by the Adams family.

At age 27, Adams joined the Sierra Club, a group dedicated to protecting the wild places of the earth, and he was hired as the summer caretaker of the Sierra Club visitor facility in Yosemite Valley, the LeConte Memorial Lodge, from 1920 to 1924.[23] He remained a member throughout his lifetime and served as a director, as did his wife. He was first elected to the Sierra Club's board of directors in 1934 and served on the board for 37 years until 1971.[5] Adams participated in the club's annual High Trips and was later responsible for several first ascents in the Sierra Nevada.

During his twenties, most of his friends had musical associations, particularly violinist and amateur photographer Cedric Wright, who became his best friend as well as his philosophical and cultural mentor. Their shared philosophy was from Edward Carpenter's Towards Democracy, a literary work which endorsed the pursuit of beauty in life and art. For several years, Adams carried a pocket edition with him while at Yosemite,[24] and it became his personal philosophy as well. He later stated, "I believe in beauty. I believe in stones and water, air and soil, people and their future and their fate."[25] He decided that the purpose of his art, whether photography or music, was to reveal that beauty to others and to inspire them to the same philosophy.

During summer, Adams would enjoy a life of hiking, camping, and photographing, and the rest of the year he worked to improve his piano playing, expanding his piano technique and musical expression. He also gave piano lessons for extra income, with which he purchased a grand piano suitable to his musical ambitions.[26] An early piano student was mountaineer and fellow Sierra Club leader Jules Eichorn.

His first photographs were published in 1921, and Best's Studio began selling his Yosemite prints the next year. His early photos already showed careful composition and sensitivity to tonal balance. In letters and cards to family, he wrote of having dared to climb to the best viewpoints and to brave the worst elements.[27] At this time, however, Adams was still planning a career in music, even though he felt that his small hands limited his repertoire.[28] It took seven more years for him to conclude that, at best, he might only become a concert pianist of limited range, an accompanist, or a piano teacher.

During the mid-1920s, Adams experimented with soft-focus, etching, bromoil process, and other techniques of the pictorial photographers, such as Photo-Secession promoter Alfred Stieglitz who strove to have photography considered equivalent to painting by trying to mimic it. However, Adams avoided hand-coloring, which was also popular at the time. He used a variety of lenses to get different effects but eventually rejected pictorialism for a more realistic approach that relied on sharp focus, heightened contrast, precise exposure, and darkroom craftsmanship.[29]

Photography career

1920s

In 1927, Adams produced his first portfolio in his new style Parmelian Prints of the High Sierras, which included his famous image Monolith, the Face of Half Dome, taken with his Korona view camera using glass plates and a dark red filter (to heighten the tonal contrasts). On that excursion, he had only one plate left, and he "visualized" the effect of the blackened sky before risking the last image. He later said, "I had been able to realize a desired image: not the way the subject appeared in reality but how it felt to me and how it must appear in the finished print".[30] In April 1927, he wrote, "My photographs have now reached a stage when they are worthy of the world's critical examination. I have suddenly come upon a new style which I believe will place my work equal to anything of its kind."[31]

Adams's first portfolio was a success, earning nearly $3,900 with the sponsorship and promotion of Albert Bender, an arts-associated businessman. Soon he received commercial assignments to photograph the wealthy patrons who bought his portfolio.[32] He also began to understand how important it was that his carefully crafted photos were reproduced to best effect. At Bender's invitation, he joined the Roxburghe Club, an association devoted to fine printing and high standards in book arts. He learned much about printing techniques, inks, design, and layout which he later applied to other projects.[33] At the time most of his darkroom work was being done in the basement of his parents' home, and he was limited by insufficient equipment.

He married Virginia Best in 1928 after an intermission from 1925 to 1926 during which he had brief relationships with various women. The newly-weds moved in with his parents to save expenses. His marriage also marked the end of his serious attempt at a musical career, as well as her ambitions to be a classical singer.

1930s

Between 1929 and 1942, Adams's work matured and he became more established. The 1930s were a particularly productive and experimental time for him. He expanded his works, emphasizing detailed close-ups as well as large forms from mountains to factories.[34]

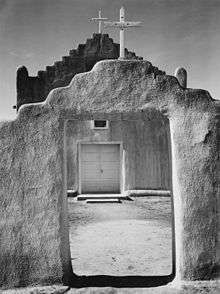

His first book Taos Pueblo was published in 1930 with text by writer Mary Hunter Austin. In New Mexico, he was introduced to notables from Stieglitz's circle, including painter Georgia O'Keeffe, artist John Marin, and photographer Paul Strand. Adams's talkative, high-spirited nature combined with his excellent piano playing made him popular among his artist friends.[35] Strand especially proved influential, sharing secrets of his technique with Adams and finally convincing Adams to pursue photography with all his talent and energy. One of Strand's suggestions which Adams adopted was to use glossy paper to intensify tonal values.

Adams was able to put on his first solo museum exhibition at the Smithsonian Institution in 1931 through a friend who had associations in Washington, D.C. The exhibition featured 60 prints taken in the High Sierra. He received a favorable review from the Washington Post: "His photographs are like portraits of the giant peaks, which seem to be inhabited by mythical gods."[36]

Despite his success, Adams felt that he was not yet up to the standards of Strand. He decided to broaden his subject matter to include still life and close-up photos, and to achieve higher quality by "visualizing" each image before taking it. He emphasized the use of small apertures and long exposures in natural light, which created sharp details with a wide range of focus, as demonstrated in Rose and Driftwood (1933), one of his finest still-life photographs.

In 1932, Adams had a group show at the M. H. de Young Museum with Imogen Cunningham and Edward Weston, and they soon formed Group f/64 which espoused "pure or straight photography" over pictorialism (f/64 being a very small aperture setting that gives great depth of field). The group's manifesto stated, "Pure photography is defined as possessing no qualities of technique, composition or idea, derivative of any other art form."[37]

Adams opened his own art and photography gallery in San Francisco in 1933, imitating Stieglitz's example.[38] He also began to publish essays in photography magazines and wrote his first instructional book Making a Photograph in 1935.[39]

During the summers, he often participated with Sierra Club High Trips outings, as a paid photographer for the group, and the rest of the year a core group of the Club members socialized regularly in San Francisco and Berkeley. In 1933, his first child Michael was born, followed by Anne two years later.[40]

During the 1930s, Adams began to deploy his photographs in the cause of wilderness preservation. He was inspired partly by the increasing desecration of Yosemite Valley by commercial development, including a pool hall, bowling alley, golf course, shops, and automobile traffic. He created the limited-edition book Sierra Nevada: The John Muir Trail in 1938, as part of the Sierra Club's efforts to secure the designation of Sequoia and Kings Canyon as national parks. This book and his testimony before Congress played a vital role in the success of the effort, and Congress designated the area as a National Park in 1940.

Yosemite Valley, to me, is always a sunrise, a glitter of green and golden wonder in a vast edifice of stone and space. I know of no sculpture, painting or music that exceeds the compelling spiritual command of the soaring shape of granite cliff and dome, of patina of light on rock and forest, and of the thunder and whispering of the falling, flowing waters. At first the colossal aspect may dominate; then we perceive and respond to the delicate and persuasive complex of nature.

— Ansel Adams, The Portfolios Of Ansel Adams

In 1935, Adams created many new photographs of the Sierra Nevada, and one of his most famous, Clearing Winter Storm, depicted the entire Yosemite Valley just as a winter storm relented, leaving a fresh coat of snow. He gathered his recent work and had a solo show at Stieglitz's "An American Place" gallery in New York in 1936. The exhibition proved successful with both the critics and the buying public, and earned Adams strong praise from the revered Stieglitz.[41]

During the rest of the 1930s, Adams took on many commercial assignments to supplement the income from the struggling Best's Studio. Until the 1970s, Adams was financially dependent on commercial projects. Some of his clients included Kodak, Fortune magazine, Pacific Gas and Electric, AT&T, and the American Trust Company.[42] He photographed Timothy L. Pflueger's new Patent Leather Bar for the St. Francis hotel in 1939.[43] The same year, he was named an editor of U.S. Camera & Travel, the most popular photography magazine at that time.[42]

1940s

In 1940, Ansel created A Pageant of Photography, the most important and largest photography show in the West to date, attended by millions of visitors.[44] With his wife, Adams completed a children's book and the very successful Illustrated Guide to Yosemite Valley during 1940 and 1941. He also taught photography by giving workshops in Detroit. Adams also began his first serious stint of teaching in 1941 at the Art Center School of Los Angeles, now known as Art Center College of Design, which included the training of military photographers.[45]

In 1943, Adams had a camera platform mounted on his station wagon, to afford him a better vantage point over the immediate foreground and a better angle for expansive backgrounds. Most of his landscapes from that time forward were made from the roof of his car rather than from summits reached by rugged hiking, as in his earlier days.[46]

On a trip in New Mexico during 1941, Adams photographed a scene of the Moon rising above a modest village with snow-covered mountains in the background, under a dominating black sky. The photograph is one of his most famous and is named Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico. Adams's description in his later books of how it was made probably enhanced the photograph's fame: the light on the crosses in the foreground was rapidly fading, and he could not find his exposure meter; however, he remembered the luminance of the Moon and used it to calculate the proper exposure.[47][48][49] Adams's earlier account[50] was less dramatic, stating simply that the photograph was made after sunset, with exposure determined using his Weston Master meter.[n 1]

However the exposure was actually determined, the foreground was underexposed, the highlights in the clouds were quite dense, and the negative proved difficult to print.[51] The initial publication of Moonrise was in U.S. Camera 1943 annual, after being selected by the "photo judge" for U.S. Camera, Edward Steichen.[52] This gave Moonrise an audience before its first formal exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1944.[53]

Over nearly 40 years, Adams re-interpreted the image, his most popular by far, using the latest darkroom equipment at his disposal, making over 1,369 unique prints, most in 16″ by 20″ format.[54] Many of the prints were made during the 1970s, finally giving Adams financial independence from commercial projects. The total value of these original prints exceeds $25,000,000;[55] the highest price paid for a single print of Moonrise reached $609,600 at Sotheby's New York auction in 2006.

In September 1941, Adams contracted[n 2] with the Department of the Interior to make photographs of National Parks, Indian reservations, and other locations for use as mural-sized prints for decoration of the department's new building. Part of his understanding with the department was that he might also make photographs for his own use, using his own film and processing.

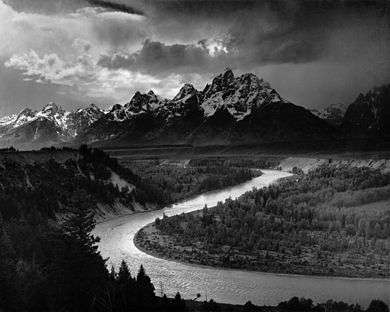

Although Adams kept meticulous records of his travel and expenses,[56] he was less disciplined about recording the dates of his images and neglected to note the date of Moonrise, so it was not clear whether it belonged to Adams or to the U.S. Government. But the position of the moon allowed the image to be eventually dated from astronomical calculations, and it was determined that Moonrise was made on November 1, 1941,[n 3] a day for which he had not billed the department, so the image belonged to Adams. The same was not true for many of his other negatives, including The Tetons and the Snake River, which, having been made for the Mural Project, became the property of the U.S. Government.[57]

When Edward Steichen formed his Naval Aviation Photographic Unit in early 1942, he wanted Adams to be a member, to build and direct a state-of-the-art darkroom and laboratory in Washington, D.C.[58] In approximately February 1942, Steichen asked Adams to join.[58] Adams agreed, with two conditions: He wanted to be commissioned as an officer, and he also told Steichen he would not be available until July 1.[59] Steichen, who wanted the team assembled as quickly as possible, passed on Adams and had his other photographers ready by early April.[59]

Adams was distressed by the Japanese American Internment that occurred after the Pearl Harbor attack. He requested permission to visit the Manzanar War Relocation Center in the Owens Valley, at the base of Mount Williamson. The resulting photo-essay first appeared in a Museum of Modern Art exhibit, and later was published as Born Free and Equal: The Story of Loyal Japanese-Americans. On release of this book, "it was met with some distressing resistance and was rejected by many as disloyal".[60]

He also contributed to the war effort by doing many photographic assignments for the military, including making prints of secret Japanese installations in the Aleutians.[61]

Adams was the recipient of three Guggenheim fellowships during his career, the first in 1946 to photograph every national park.[62] This series of photographs produced memorable images of Old Faithful Geyser, Grand Teton, and Mount McKinley. At that time, there were 28 national parks, and Adams photographed 27 of them, missing only Everglades National Park in Florida.

In 1945, Adams was asked to form the first fine art photography department at the San Francisco Art Institute. Adams invited Dorothea Lange, Imogen Cunningham and Edward Weston to be guest lecturers and Minor White to be main instructor.[63] The photography department produced numerous notable photographers, including Philip Hyde, Benjamen Chinn, Bill Heick, and C. Cameron Macauley.

1950s

In 1952 Adams was one of the founders of the magazine Aperture, which was intended as a serious journal of photography displaying its best practitioners and newest innovations. He was also a contributor to Arizona Highways, a photo-rich travel magazine. His article on Mission San Xavier del Bac, with text by longtime friend Nancy Newhall, was enlarged into a book published in 1954. This was the first of many collaborations with her.[64]

In June 1955, Adams began his annual workshops, teaching thousands of students until 1981,[65] He continued with commercial assignments for another twenty years, and became a consultant with a monthly retainer for Polaroid Corporation, which was founded by good friend Edwin Land.[66] He made thousands of photographs with Polaroid products, El Capitan, Winter, Sunrise (1968) being the one he considered his most memorable. During the final twenty years of his life, the 6x6cm medium format Hasselblad was his camera of choice, with Moon and Half Dome (1960) being his favorite photograph made with that marque of camera.[67]

Adams published his fourth portfolio, What Majestic Word, in 1963, and dedicated it to the memory of his Sierra Club friend Russell Varian,[68] who was a co-inventor of the klystron and who had died in 1959. The title was taken from the poem "Sand Dunes," by John Varian, Russell's father,[18] and the fifteen photographs were accompanied by the writings of both John and Russell Varian. Russell's widow, Dorothy, wrote the preface, and explained that the photographs were selected to serve as interpretations of the character of Russell Varian.[68]

Later career

In the 1960s, a few mainstream art galleries (without a photographic emphasis), which originally would have considered photos unworthy of exhibit alongside fine paintings, decided to show Adams's images, particularly the former Kenmore Gallery in Philadelphia.[69] In March 1963, Ansel Adams and Nancy Newhall accepted a commission from Clark Kerr, the president of the University of California, to produce a series of photographs of the university's campuses to commemorate its centennial celebration. The collection, titled Fiat Lux after the university's motto, was published in 1967 and now resides in the Museum of Photography at the University of California, Riverside.

In 1974, Adams was guest of honor at the Rencontres d'Arles festival in France. An evening screening at the Arles's Théâtre Antique and an exhibition were presented. The festival celebrated the artist three more times after that: in 1976, 1982 and 1985, through screenings and exhibitions.

In 1974, Adams had a major retrospective exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Much of his time during the 1970s was spent curating and reprinting negatives from his vault, in part to satisfy the great demand of art museums which had finally created departments of photography and desired his works. He also devoted his considerable writing skills and prestige to the cause of environmentalism, emphasizing particularly the Big Sur coastline of California and the protection of Yosemite from overuse. President Jimmy Carter commissioned him to make the first official portrait of a president made by a photograph.[70] That year he also cofounded the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona, which handles some of his estate matters.[71]

Death and legacy

Adams died from cardiovascular disease on April 22, 1984, in the Intensive-care unit at the Community Hospital of the Monterey Peninsula in Monterey, California, at age 82. He was surrounded by his wife, children Michael and Anne, and five grandchildren.[72]

Publishing rights for most of Adams's photographs are handled by the trustees of The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. An archive of Adams's work is located at the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona in Tucson. Numerous works by the artist have been sold at auction, including a mural-sized print of Clearing Winter Storm, Yosemite National Park, which sold at Sotheby's New York in 2010 for $722,500, the highest price ever paid for an original Ansel Adams photograph.[73]

John Szarkowski states in the introduction to Ansel Adams: Classic Images (1985, p. 5), "The love that Americans poured out for the work and person of Ansel Adams during his old age, and that they have continued to express with undiminished enthusiasm since his death, is an extraordinary phenomenon, perhaps even unparalleled in our country's response to a visual artist."

Contributions and influence

Landscapes of the American West

Romantic landscape artists Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran portrayed the Grand Canyon and Yosemite during the 19th century and were subsequently displaced by photographers Carleton Watkins, Eadweard Muybridge, and George Fiske.[74] But it was Adams's black-and-white photographs of the West which became the foremost record of what many of the National Parks were like before tourism, and his persistent advocacy helped expand the National Park system. He used his works to promote many of the goals of the Sierra Club and of the nascent environmental movement, but always insisted that, for his photographs, "beauty comes first".

Art critic John Szarkowski wrote "Ansel Adams attuned himself more precisely than any photographer before him to a visual understanding of the specific quality of the light that fell on a specific place at a specific moment. For Adams the natural landscape is not a fixed and solid sculpture but an insubstantial image, as transient as the light that continually redefines it. This sensibility to the specificity of light was the motive that forced Adams to develop his legendary photographic technique."[75]

In 1955 Edward Steichen selected Adams' Mount Williamson for the world-touring Museum of Modern Art exhibition The Family of Man[76] that was seen by 9 million visitors. It was the largest print in the exhibition, 3m x 3.6m (10 x 12 feet) in size, presented floor-to-ceiling in a prominent position as the backdrop to the section 'Relationships'[77] as a reminder of the essential reliance of humanity on the soil. Despite its striking and prominent display, Adams, however, expressed displeasure at the 'gross' enlargement and 'poor' quality of the print.[78]

Environmental protection

Realistic about land development and the subsequent loss of habitat, Adams advocated for balanced growth but was troubled by the ravages of "progress". He stated, "We all know the tragedy of the dustbowls, the cruel unforgivable erosions of the soil, the depletion of fish or game, and the shrinking of the noble forests. And we know that such catastrophes shrivel the spirit of the people... The wilderness is pushed back, man is everywhere. Solitude, so vital to the individual man, is almost nowhere."[79]

Group f/64 and the Zone System

Adams co-founded Group f/64 with other masters like Edward Weston, Willard Van Dyke, and Imogen Cunningham. With Fred Archer, he pioneered the Zone System, a technique for translating perceived light into specific densities on negatives and paper, giving photographers better control over finished photographs. Adams also advocated the idea of visualization (which he often termed "previsualization", though he later acknowledged that term to be a redundancy) whereby the final image is "seen" by the mind before the photo is taken, toward the goal of achieving all together the aesthetic, intellectual, spiritual, and mechanical effects desired. He taught these and other techniques to thousands of amateur photographers through his publications and his workshops. His many books about photography, including the Morgan & Morgan Basic Photo Series (The Camera, The Negative, The Print, Natural Light Photography, and Artificial Light Photography) have become classics in the field.

Friendship with Georgia O'Keefe

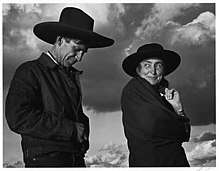

Adams met Georgia O'Keeffe in Taos, New Mexico in 1929, and they became lifelong friends. Their works set in the desert Southwest have been often published and exhibited together. Adams made a candid 1937 portrait of O'Keeffe with Orville Cox, the head wrangler at Ghost Ranch, on the rim of Canyon de Chelly. Adams once remarked, “Some of my best photographs have been made in and on the rim of [that] canyon.”[80]

Awards and honors

Adams received a number of awards during his lifetime and posthumously, and there have been a few awards named for him.[81]

Adams's photograph The Tetons and the Snake River was one of the 115 images recorded on the Voyager Golden Record aboard the Voyager spacecraft. These images were selected to convey information about humans, plants and animals, and geological features of the Earth to a possible alien civilization.

Adams received an honorary artium doctor degree from Harvard University and an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degree from Yale University. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1966.[82]

In 1968, he was awarded the Conservation Service Award by the Department of the Interior. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor.

Adams received the Sierra Club John Muir Award in 1963,[83] the Hasselblad Award in 1981[84], and was inducted into the California Hall of Fame by California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and First Lady Maria Shriver in 2007.[85]

The Minarets Wilderness in the Inyo National Forest and a 11,760-foot (3,580 m) peak therein were renamed the Ansel Adams Wilderness and Mount Ansel Adams respectively in 1985.

The Sierra Club's Ansel Adams Award for Conservation Photography was established in 1971,[83] and the Ansel Adams Award for Conservation was established in 1980 by The Wilderness Society.[86] The Wilderness Society also has a large permanent gallery of his work on display at its Washington, D.C. headquarters.[87]

Works

Color photographs

Adams was known mostly for his boldly printed, large format black-and-white images, but he also worked extensively with color.[88] However, he preferred black-and-white photography, which he believed could be manipulated to produce a wide range of bold, expressive tones, and he felt constricted by the rigidity of the color process.[89] Most of his color work was done on assignments, and he did not consider his color work to be important or expressive, even explicitly forbidding any posthumous exploitation of his color work.

Notable photographs

- Monolith, The Face of Half Dome, Yosemite National Park, 1927.

- Rose and Driftwood, San Francisco, California, 1932.

- Georgia O'Keeffe and Orville Cox, Canyon de Chelly National Monument, 1937.

- Clearing Winter Storm, Yosemite National Park, 1940.[73]

- Moon and Half Dome, Yosemite National Park, California, 1960.

- Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico, 1941.

- Winter Sunrise, Sierra Nevada, from Lone Pine, California, 1944.

- Aspens, Northern New Mexico, 1958.

- El Capitan, Winter Sunrise, 1968.

Photographic books

- Parmelian Prints of the High Sierras, 1927. (Grabhorn Press)

- Taos Pueblo, 1930.

- Sierra Nevada the John Muir Trail, 1938. (reprinted 2006 as ISBN 0-8212-5717-X).

- Born Free and Equal, 1944. ISBN 1-893343-05-7.

- Yosemite and the Sierra Nevada, 1948. (text from writings of John Muir)

- My Camera In The National Parks, 1950.

- The Land of Little Rain, 1950. (text by Mary Hunter Austin)

- The Islands of Hawaii, 1958.

- This is the American Earth, 1960, (with Nancy Newhall) Sierra Club Books. (reprinted by Bulfinch, ISBN 0-8212-2182-5)

- These We Inherit: The Parklands of America, 1962. (with Nancy Newhall)

- The Eloquent Light, 1963. (unfinished biography of Adams by Nancy Newhall)

- Yosemite Valley", 1967. (45 plates in B&W edited by Nancy Newhall, published by 5 Associates, Redwood City, California.)

- The Tetons and the Yellowstone, 1970.

- Ansel Adams, 1972. ISBN 0-8212-0721-0.

- Images, 1923–1974, 1974. ISBN 0-8212-0600-1.

- Polaroid Land Photography, 1978. ISBN 0-8212-0729-6.

- Yosemite and the Range of Light, 1979. ISBN 0-8212-0750-4.

- The Portfolios of Ansel Adams, 1981. ISBN 0-8212-0723-7.

- Examples: The Making of 40 Photographs, 1984. ISBN 0-8212-1551-5.

- An Autobiography, 1984. ISBN 978-0821215968.

- Ansel Adams: Classic Images, 1986. ISBN 0-8212-1629-5.

- Letters and Images 1916–1984, 1988. ISBN 0-8212-1691-0.

- Our Current National Parks, 1992.

- Ansel Adams: In Color, 1993. ISBN 0-8212-1980-4.

- Photographs of the Southwest, 1994. ISBN 0-8212-0699-0.

- Yosemite and the High Sierra, 1994. ISBN 0-8212-2134-5.

- The National Park Photographs, 1995. ISBN 0-89660-056-4.

- Yosemite, 1995. ISBN 0-8212-2196-5.

- California, 1997. ISBN 0-8212-2369-0.

- America's Wilderness, 1997. ISBN 1-56138-744-4.

- Ansel Adams at 100, 2001. ISBN 0-8212-2515-4.

- Born Free and Equal, 2002. ISBN 1-893343-05-7.

- Ansel Adams: The National Park Service Photographs, 2005. ISBN 978-0-89660-056-0.

- Ansel Adams: The Spirit of Wild Places, 2005. ISBN 1-59764-069-7.

- Ansel Adams: 400 Photographs, 2007. ISBN 978-0-316-11772-2.

- Ansel Adams in the National Parks: Photographs from America's Wild Places, 2010. ISBN 978-0-316-07846-7.

- Ansel Adams in the Canadian Rockies, 2013. ISBN 978-0-316-24341-4.

- Ansel Adams in Yosemite Valley: Celebrating the Park at 150, 2014. ISBN 978-0316323406.

Technical books

- Making a Photograph, 1935.

- Camera and Lens: The Creative Approach, 1948. ISBN 0-8212-0716-4.

- The Negative: Exposure and Development, 1949. ISBN 0-8212-0717-2.

- The Print: Contact Printing and Enlarging, 1950. ISBN 0-8212-0718-0.

- Natural Light Photography, 1952. ISBN 0-8212-0719-9.

- Artificial Light Photography, 1956. ISBN 0-8212-0720-2.

- Examples: The Making of 40 Photographs, 1983. ISBN 0-8212-1750-X.

- The Camera, 1995. ISBN 0-8212-2184-1.

- The Negative, 1995. ISBN 0-8212-2186-8.

- The Print, 1995. ISBN 0-8212-2187-6.

Notes

- ↑ Alinder 1996, p. 192, states that the image caption for Moonrise in U.S. Camera 1943 was inaccurate, citing discrepancies in several technical details.

- ↑ Although verbal agreement was given on September 30, 1941, the contract was actually approved on November 3 and backdated to October 14 (Wright & Armor 1988, p. vi).

- ↑ David Elmore of the High Altitude Observatory in Boulder, Colorado, determined that Moonrise was taken on October 31, 1941, at 4:03 pm (Callahan 1981, pp. 30–31). Dennis di Cicco of Sky & Telescope magazine noticed that the moon's position at the time Elmore had determined did not match the Moon's position in the image, and after an independent analysis, determined the time to be 4:49:20 pm on November 1, 1941. He reviewed his results with Elmore, who agreed with di Cicco's conclusions (di Cicco 1991, pp. 529–33).

References

- ↑ "Legacy: Think Like Ansel Adams Today". Outdoor Photographer. Werner. February 3, 2009. Retrieved January 17, 2013.

- ↑ Adams 1985, p. 4.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, p. 4.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, p. 2.

- 1 2 Sierra Club 2008a.

- ↑ Whittington 2010.

- 1 2 Alinder 1996, p. 6.

- ↑ Adams 1985, p. 14.

- ↑ "Lands End". San Francisco, CA: Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy. Archived from the original on April 12, 2010. Retrieved April 19, 2010.

- ↑ Aitken, R. G. (1951). "In Memoriam, Charles Hitchcock Adams 1868–1951". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, Vol. 63 No. 375. San Francisco, CA: Astronomical Society of the Pacific. pp. 284–286. Retrieved April 19, 2010.

- ↑ Adams 1985, p. 40.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, p. 9.

- 1 2 Alinder 1996, p. 11.

- ↑ Adams 1985, p. 18.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, p. 276.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, p. 52.

- ↑ Adams 1985, p. 45.

- 1 2 A. Hammond, p. 15

- ↑ Stillman 2007, p. 12.

- ↑ Adams 1985, p. 53.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, p. 36.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, p. 23.

- ↑ "Environmental Education – LeConte Memorial Lodge". San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club. Archived from the original on March 4, 2010. Retrieved April 19, 2010.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, p. 47.

- ↑ Adams 1985, p. 9.

- ↑ Adams 1985, p. 27.

- ↑ Alinder et al. 1988, p. 3.

- ↑ Adams 1985, p. 28.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, pp. 38–42.

- ↑ Adams 1985, p. 76.

- ↑ Alinder et al. 1988, p. 30.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, p. 62.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, p. 68.

- ↑ ArtInfo 2006.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, pp. 73–74.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, p. 77.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, p. 87.

- ↑ Adams 1985, p. 115.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, p. 114.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, p. 102.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, p. 120.

- 1 2 Alinder 1996, p. 158.

- ↑ Hamlin 2003.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, p. 159.

- ↑ Adams 1985, p. 312.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, p. 239.

- ↑ Adams 1981, p. 127.

- ↑ Adams 1985, pp. 273–275.

- ↑ Adams 1983, pp. 40–43.

- ↑ Maloney 1942, pp. 88–89.

- ↑ Adams 1983, p. 42.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, p. 192.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, p. 193.

- ↑ Andrew Smith Gallery 2008.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, pp. 189–199.

- ↑ Wright & Armor 1988, p. vi.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, p. 201.

- 1 2 Alinder 1996, p. 172.

- 1 2 Alinder 1996, p. 173.

- ↑ Adams 1985, p. 263.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, p. 175.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, p. 217.

- ↑ Vernacular Language North, p. 5.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, p. 251.

- ↑ Adams 1985, p. 316.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, p. 260.

- ↑ Adams 1985, p. 375.

- 1 2 A. Hammond, p. 108

- ↑ Goldbloom 1990, p. 3.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, pp. 294–295.

- ↑ "Ansel Adams – Center for Creative Photography".

- ↑ Alinder et al. 1988, p. 396.

- 1 2 Ilnytzky 2010.

- ↑ Alinder 1996, p. 33.

- ↑ Szarkowski 1976.

- ↑ Mason, Jerry, ed. (1955). The family of man : the photographic exhibition. Steichen, Edward (organizer); Sandburg, Carl (writer of foreword); Norman, Dorothy (writer of added text); Lionni, Leo (book designer); Stoller, Ezra (photographer). Published for the Museum of Modern Art by Simon and Schuster in collaboration with the Maco Magazine Corporation.

- ↑ Sollors, Werner (2018) "The Family of Man: Looking at the Photographs Now and Remembering a Visit in the 1950s" in Hurm, Gerd; Reitz, Anke; Zamir, Shamoon, eds. (2018). The family of man revisited : photography in a global age. London I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-78672-297-3.

- ↑ Sandeen, Eric J (1995). Picturing an exhibition : the family of man and 1950s America (1st ed.). University of New Mexico Press. p. 47, 59, 169. ISBN 978-0-8263-1558-8.

- ↑ Adams 1985, pp. 290–291.

- ↑ Siobhán Bohnacker (December 16, 2013). "Picture Desk: The Faraway". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2018-05-29.

- ↑ Ansel Adams Gallery.

- ↑ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter A" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 10, 2011. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- 1 2 Sierra Club 2008b.

- ↑ Hasselblad Foundation 1981.

- ↑ California Museum 2007.

- ↑ Wilderness Society.

- ↑ "Ansel Adams Collection". wilderness.org.

- ↑ "Ansel Adams Photographs". Center for Creative Photography at University of Arizona Libraries. Archived from the original on July 25, 2010.

- ↑ Woodward, Richard. "Ansel Adams in Color". Smithsonian Magazine.

Sources

- Adams, Ansel (1981). The Negative. Boston: Little Brown. ISBN 0-8212-1131-5.

- Adams, Ansel (1985). Ansel Adams, an Autobiography. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-8212-1596-5.

- Adams, Ansel (1989). Examples. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-8212-1750-X.

- Alinder, Mary (1996). Ansel Adams: A Biography. New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0-8050-4116-8.

- Alinder, Mary; Stillman, Andrea; Adams, Ansel; Stegner, Wallace (1988). Ansel Adams: Letters and Images 1916–1984. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-8212-1691-0.

- Andrew Smith Gallery. "5 prints of "Moonrise", 1941–1975". Andrew Smith Gallery.

- Ansel Adams Gallery. "Biography". Ansel Adams Gallery. Archived from the original on October 6, 2009.

- Artinfo (2006). "Ansel Adams at the Phoenix Art Museum". Artinfo. Retrieved November 29, 2006.

- California Museum (2007). "Adams inducted into California Hall of Fame". California Museum. Archived from the original on April 11, 2008. Retrieved April 16, 2008.

- Callahan, Sean (1981). "Short Takes: Countdown to Moonrise". American Photographer (January 1981).

- di Cicco, Dennis (1991). "Dating Ansel Adams' Moonrise". Sky & Telescope (November 1991).

- Goldbloom, J. (1990). "Remembering the Kenmore" in Philly Art Walks. Fall 1990.

- Hamlin, Jesse (December 20, 2003). "Raise a toast to Ansel Adams. Sure, he was known for landscapes, but there was more to his portfolio, as these bar photos show". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

- Hammond, Anne (2002). Ansel Adams: divine performance. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09241-7.

- Ilnytzky, Una (June 23, 2010). "Ansel Adams Yosemite photo fetches $722K in record-setting auction".

- Maloney, T.J. (1942). U.S. Camera 1943 annual. New York: Duell, Sloan & Pearce.

- Papanikolas, Theresa, Georgia O'Keeffe and Ansel Adams, The Hawai'I Pictures, Honolulu Museum of Art, 2013

- Read, Michael (1993). Michael Read, ed. Ansel Adams, New light: Essays on His Legacy and Legend. San Francisco: The Friends of Photography.

- Sierra Club. "Roster of Sierra Club Directors" (PDF). Sierra Club. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- Sierra Club (2008a). "Ansel Adams and the Sierra Club: About Ansel Adams". Sierra Club. Archived from the original on February 1, 2010. Retrieved February 26, 2010.

- Hasselblad Foundation (1981). "Ansel Adams". Hasselblad Foundation.

- Sierra Club (2008b). "Award Winners". Sierra Club.

- Stillman, Andrea G. (2007). 400 Photographs. New York City: Little, Brown. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-316-11772-2.

- Szarkowski, John (1976). Looking at Photographs: 100 Pictures from the Collection of the Museum of Modern Art. New York: N.Y. Graphic Society.

- Vernacular Language North. "SF Bay Area Timeline: Modernism (1930–1960)". Vernacular Language North.

- Whittington, Geoff (January 24, 2010). "Ansel Adams' boyhood San Francisco house". San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco, CA. Archived from the original on May 5, 2010. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- Wilderness Society. "The Wilderness Society".

- Wright, Peter; Armor, John (1988). The Mural Project. Santa Barbara: Reverie Press. ISBN 1-55824-162-0.

External links

- Works by or about Ansel Adams in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- American Memory – Ansel Adams "Suffering Under a Great Injustice" Ansel Adams's Photographs of Japanese-American Internment at Manzanar From the American Memory Collection of the Library of Congress.

- Records of the National Park Service – Ansel Adams Photographs 226 high-resolution photographs from National Archives Still Picture Branch.

- All Ansel Adams Images Online Center for Creative Photography (CCP) CCP at the University of Arizona has released a digital catalog of all Adams's images.