Strasserism

| Part of a series on |

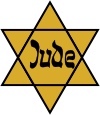

| Antisemitism |

|---|

Part of Jewish history |

|

Antisemitic publications |

|

Opposition |

|

|

Strasserism (German: Strasserismus or Straßerismus) is a strand of Nazism that calls for a more radical, mass-action and worker-based form of Nazism—hostile to Jews not from a racial, ethnic, cultural or religious perspective, but from an anti-capitalist basis—to achieve a national rebirth. It derives its name from Gregor and Otto Strasser, the two Nazi brothers initially associated with this position.

Opposed on strategic views to Adolf Hitler, Otto Strasser was expelled from the Nazi Party in 1930 and went into exile in Czechoslovakia while Gregor Strasser was murdered in Germany on 30 June 1934 during the Night of the Long Knives. Strasserism remains an active position within strands of neo-Nazism.

Strasser brothers

Gregor Strasser

Gregor Strasser (1892–1934) began his career in ultranationalist politics by joining the Freikorps after serving in World War I. Strasser was involved in the Kapp Putsch and formed his own völkischer Wehrverband ("popular defense union") which he merged into the NSDAP in 1921. Initially a loyal supporter of Adolf Hitler, he took part in the Beer Hall Putsch and held a number of high positions in the Nazi Party. However, Strasser soon became a strong advocate of the socialist wing of the party, arguing that the national revolution should also include strong action to tackle poverty and should seek to build working class support. After Hitler's rise to power, Ernst Röhm, who headed the Sturmabteilung (SA), then the most important paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party, called for a second revolution aimed at removing the elites from control. This was opposed by the conservative movement as well as by some Nazis who preferred an ordered authoritarian regime to the radical and disruptive program proposed by the party's left-wing.

Otto Strasser

Otto Strasser (1897–1974) had also been a member of the Freikorps, but he joined the Social Democratic Party and fought against the Kapp Putsch. Strasser joined the Nazi Party in 1925, but he nonetheless retained his ideas about the importance of socialism. Considered more of a radical than his brother, Strasser was expelled by the Nazi Party in 1930 and set up his own dissident group, the Black Front, which called for a specifically German nationalist form of socialist revolution. Strasser fled Germany in 1933 to live firstly in Czechoslovakia and then Canada before returning to West Germany in later life, all the while writing prolifically about Hitler and what he saw as his betrayal of national socialist ideals.

Ideology

The name Strasserism came to be applied to the form of Nazism that developed around the Strasser brothers. Although they had been involved in the creation of the National Socialist Program of 1920, both called on the party to commit to "breaking the shackles of finance capital".[1] This opposition to Jewish finance capitalism, which they contrasted to "productive capitalism, was shared by Hitler himself, who borrowed it from Gottfried Feder.[2]

This populist and antisemitic form of anti-capitalism was further developed in 1925 when Otto Strasser published the Nationalsozialistische Briefe, which discussed notions of class conflict, wealth redistribution and a possible alliance with the Soviet Union. His 1930 follow-up Ministersessel oder Revolution (Cabinet Seat or Revolution) went further by attacking Hitler's betrayal of the socialist aspect of Nazism as well as criticizing the notion of the Führerprinzip.[3] Whilst Gregor Strasser echoed many of the calls of his brother, his influence on the ideology is less, owing to his remaining in the Nazi Party longer and to his early death. Meanwhile, Otto Strasser continued to expand his argument, calling for the break-up of large estates and the development of something akin to a guild system and the related establishment of a Reich cooperative chamber to take a leading role in economic planning.[4]

Strasserism therefore became a distinct strand of Nazism that whilst holding on to previous Nazi ideals such as palingenetic ultranationalism and antisemitism, added a strong critique of capitalism and framed this in the demand for a more socialist-based approach to economics.

However, it is disputed whether Strasserism was a distinct form of Nazism. According to historian Ian Kershaw, "the leaders of the SA [which included Gregor Strasser] did not have another vision of the future of Germany or another politic to propose". The Strasserites advocated the radicalization of the Nazi regime and the toppling of the German elites, calling Hitler's rise to power a half-revolution which needed to be completed.[5]

Influence

In Germany

During the 1970s, the ideas of Strasserism began to be referred to more in European far-right groups as younger members with no ties to Hitler and a stronger sense of anti-capitalism came to the fore. Strasserite thought in Germany began to emerge as a tendency within the National Democratic Party (NPD) during the late 1960s. These Strasserites played a leading role in securing the removal of Adolf von Thadden from the leadership and after his departure the party became stronger in condemning Hitler for what it saw as his move away from socialism in order to court business and army leaders.[6]

Although initially adopted by the NPD, Strasserism soon became associated with more peripheral extremist figures, notably Michael Kühnen who produced a 1982 pamphlet Farewell to Hitler, which included a strong endorsement of the idea. The People's Socialist Movement of Germany/Labour Party (a minor extremist movement that was outlawed in 1982) adopted the policy while its successor movement, the Nationalist Front, did likewise, with its ten-point programme calling for an "anti-materialist cultural revolution" and an "anti-capitalist social revolution" to underline its support for the idea.[7] The Free German Workers' Party also moved towards these ideas under the leadership of Friedhelm Busse in the late 1980s.[8]

The flag of the Strasserite movement Black Front and its symbol a crossed hammer and a sword has been used by German and other European neo-Nazis abroad as a substitute for the more infamous Nazi flag which is banned in some countries such as Germany.

In the United Kingdom

Strasserism emerged in the United Kingdom in the early 1970s and centred on the National Front (NF) publication Britain First, the main writers of which were David McCalden, Richard Lawson and Denis Pirie. Opposing the leadership of John Tyndall, they formed an alliance with John Kingsley Read and ultimately followed him into the National Party (NP).[9] The NP called for British workers to seize the right to work and offered a fairly Strasserite economic policy.[10] Nonetheless, the NP failed to last for very long. Due in part to Read's lack of enthusiasm for Strasserism, the main exponents of the idea drifted away.

The idea was reintroduced to the NF by Andrew Brons in the early 1980s when he decided to make the party's ideology clearer.[11] However, Strasserism was soon to become the province of the radicals in the Official National Front, with Richard Lawson brought in a behind-the-scenes role to help direct policy.[12] This Political Soldier wing ultimately opted for the indigenous alternative of distributism, but their strong anti-capitalist rhetoric as well as that of their International Third Position successor demonstrated influences from Strasserism. From this background, Troy Southgate emerged, whose own ideology and those of related groups such as the English Nationalist Movement and National Revolutionary Faction were influenced by Strasserism. He has also described himself as a post-Strasserite.

Elsewhere

Third Position groups, whose inspiration is generally more Italian in derivation, have often looked to Strasserism, owing to their strong opposition to capitalism. This was noted in France, where the student group Groupe Union Défense and the more recent Renouveau français both extolled Strasserite economic platforms.[13]

Attempts to reinterpret Nazism as having a left-wing base have also been heavily influenced by this school of thought, notably through the work of Povl Riis-Knudsen, who produced the Strasser-influenced work National Socialism: A Left-Wing Movement in 1984.

In the United States, Tom Metzger also flirted with Strasserism, having been influenced by Kühnen's pamphlet.[14]

See also

References

- Notes

- ↑ C.T. Husbands, 'Militant Neo-Nazism in the Federal Republic of Germany' in L. Cheles, R. Ferguson & M. Vaughan, Neo-Fascism in Europe, 1992, p. 98.

- ↑ Ian Kershaw, Hitler: A Profile in Power, first chapter (London, 1991, rev. 2001).

- ↑ Karl Dietrich Bracher, The German Dictatorship, 1973, pp. 230–231.

- ↑ Nolte, Ernst (1969). Three Faces of Fascism: Action Française, Italian fascism, National Socialism. New York: Mentor. pp. 425–426.

- ↑ Ian Kershaw, 1991, chapter III, first section.

- ↑ R. Eatwell, Fascism: A History, 2003, p. 283.

- ↑ C.T. Husbands, "Militant Neo-Nazism in the Federal Republic of Germany" in L. Cheles, R. Ferguson, M. Vaughan, Neo-Fascism in Europe, 1992, pp. 99–100.

- ↑ C.T. Husbands, "Militant Neo-Nazism in the Federal Republic of Germany" in L. Cheles, R. Ferguson, M. Vaughan, Neo-Fascism in Europe, 1992, p. 97.

- ↑ N. Copsey, Contemporary British Fascism: The British National Party and the Quest for Legitimacy, 2004, pp. 17–18.

- ↑ M. Walker, The National Front, 1977, p. 194.

- ↑ N. Copsey, Contemporary British Fascism: The British National Party and the Quest for Legitimacy, 2004, pp. 33–34.

- ↑ G. Gable, 'The Far Right in Contemporary Britain' in L. Cheles, R. Ferguson & M. Vaughan, Neo-Fascism in Europe, 1992, p. 97.

- ↑ R. Griffin, The Nature of Fascism, 1993, p. 166.

- ↑ M.A. Lee, The Beast Reawakens, 1997, p. 257.

- Further reading

- Bolton, K. R. "Otto Strasser's 'Europe'" in Southgate, Troy ed. (2017) Eye of the Storm. The Conservative Revolutionaries of 1920s, 1930s and 1940s Germany, London: Black Front Press, pp. 7–31.

- Reed, Douglas (1940) Nemesis: The Story of Otto Strasser.

- Reed, Douglas (1953) The Prisoner of Ottawa: Otto Strasser.

External links