Fascism and ideology

| Part of a series on |

| Fascism |

|---|

|

|

Organizations |

|

Lists |

|

Variants

|

|

The history of Fascist ideology is long and it involves many sources. Fascists took inspiration from as far back as the Spartans for their focus on racial purity and their emphasis on rule by an elite minority. It has also been connected to the ideals of Plato, though there are key differences. In Italy, Fascism styled itself as the ideological successor to Rome, particularly the Roman Empire. The Enlightenment-era concept of a "high and noble" Aryan culture as opposed to a "parasitic" Semitic culture was core to Nazi racial views. From the same era, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's view on the absolute authority of the state also strongly influenced Fascist thinking. The French Revolution was a major influence insofar as the Nazis saw themselves as fighting back against many of the ideas which it brought to prominence, especially liberalism, liberal democracy and racial equality, whereas on the other hand Fascism drew heavily on the revolutionary ideal of nationalism. Common themes among fascist movements include; nationalism (including racial nationalism), hierarchy and elitism, militarism, quasi-religion, masculinity and voluntarism. Other aspects of fascism such as it's "myth of decadence", anti‐egalitarianism and totalitarianism can be seen to originate from these ideas. These fundamental aspects however, can be attributed to a concept known as "Palingenetic ultranationalism", a theory proposed by Roger Griffin, that fascism is essentially populist ultranationalism sacralized through myth of national rebirth and regeneration.

Its relationship with other ideologies of its day were complex, often at once adversarial and focused on co-opting their more popular aspects. Fascists supported limited private property rights and the profit motive of capitalism, but sought to eliminate the autonomy of large-scale capitalism by consolidating power with the state. They shared many goals with and often allied with the conservatives of their day and often recruited from disaffected conservative ranks, but presented themselves as holding a more modern ideology, with less focus on things like traditional religion. Fascism opposed the egalitarian (Völkisch equality) and international character of mainstream socialism, but sometimes sought to establish itself as an alternative "national" socialism. It strongly opposed liberalism, classical liberalism, communism and democratic socialism.

Ideological origins

Early influences (495 BC–1880 AD)

Early influences that shaped the ideology of fascism have been dated back to Ancient Greece. The political culture of ancient Greece and specifically the ancient Greek city state of Sparta under Lycurgus, with its emphasis on militarism and racial purity, were admired by the Nazis.[1][2] Nazi Führer Adolf Hitler emphasized that Germany should adhere to Hellenic values and culture – particularly that of ancient Sparta.[1] He rebuked potential criticism of Hellenic values being non-German by emphasizing the common Aryan race connection with ancient Greeks, saying in Mein Kampf: "One must not allow the differences of the individual races to tear up the greater racial community".[3] Hitler went on to say in Mein Kampf: "The struggle that rages today involves very great aims: a culture fights for its existence, which combines millenniums and embraces Hellenism and Germanity together".[3] The Spartans were emulated by the quasi-fascist regime of Ioannis Metaxas who called for Greeks to wholly commit themselves to the nation with self-control as the Spartans had done.[4] Supporters of the 4th of August Regime in the 1930s to 1940s justified the dictatorship of Metaxas on the basis that the "First Greek Civilization" involved an Athenian dictatorship led by Pericles who had brought ancient Greece to greatness.[4] The Greek philosopher Plato supported many similar political positions to fascism.[5] In The Republic (c. 380 BC),[6] Plato emphasizes the need for a philosopher king in an ideal state.[6] Plato believed the ideal state would be ruled by an elite class of rulers known as “Guardians” and rejected the idea of social equality.[5] Plato believed in an authoritarian state.[5] Plato held Athenian democracy in contempt by saying: "The laws of democracy remain a dead letter, its freedom is anarchy, its equality the equality of unequals".[5] Like fascism, Plato emphasized that individuals must adhere to laws and perform duties while declining to grant individuals rights to limit or reject state interference in their lives.[7] Like fascism, Plato also claimed that an ideal state would have state-run education that was designed to promote able rulers and warriors.[8] Like many fascist ideologues, Plato advocated for a state-sponsored eugenics program to be carried out in order to improve the Guardian class in his Republic through selective breeding.[9] Italian Fascist Il Duce Benito Mussolini had a strong attachment to the works of Plato.[10] However, there are significant differences between Plato's ideals and fascism.[8] Unlike fascism, Plato never promoted expansionism and he was opposed to offensive war.[8]

Italian Fascists identified their ideology as being connected to the legacy of ancient Rome and particularly the Roman Empire: Julius Caesar and Augustus were idolized by Italian Fascists.[11] Italian Fascism views the modern state of Italy as the heir of the Roman Empire and emphasized the need for renovation of Italian culture to "return to Roman values".[12] Italian Fascists identify the Roman Empire as being an ideal organic and stable society in contrast to contemporary individualist liberal society that they identify as being chaotic in comparison.[12] Julius Caesar has been identified as a role model by fascists because he led a revolution that overthrew an old order to establish a new order based on a dictatorship in which Julius Caesar wielded absolute power.[13] Mussolini emphasized the need for dictatorship, activist leadership style and the leader cult like that of Julius Caesar that involved "the will to fix a unifying and balanced centre and a common will to action".[14] Italian Fascists also idolized Augustus as the champion who built the Roman Empire.[13] The fasces – a symbol of Roman authority – was the symbol of the Italian Fascists and was additionally adopted by many other national fascist movements formed in emulation of Italian fascism.[15] While a number of Nazis rejected Roman civilization because they saw it as incompatible with Aryan Germanic culture and they also believed that Aryan Germanic culture was outside Roman culture, Adolf Hitler personally admired ancient Rome.[15] Hitler focused on ancient Rome during its rise to dominance and at the height of its power as a model to follow and Hitler deeply admired the Roman Empire for its ability to forge a strong and unified civilization and in private conversations he blamed the fall of the Roman Empire on the Roman adoption of Christianity because he claimed that Christianity authorized the racial intermixing that weakened Rome and led to its destruction.[14]

There were a number of influences on fascism from the Renaissance era in Europe. Niccolò Machiavelli is known to have influenced Italian Fascism, particularly his promotion of the absolute authority of the state.[6] Machiavelli rejected all existing traditional and metaphysical assumptions of the time—especially those associated with the Middle Ages—and asserted as an Italian patriot that Italy needed a strong and all-powerful state led by a vigorous and ruthless leader who would conquer and unify Italy.[16] Mussolini saw himself as a modern-day Machiavellian and wrote an introduction to his honorary doctoral thesis for the University of Bologna—"Prelude to Machiavelli".[17] Mussolini professed that Machiavelli's "pessimism about human nature was eternal in its acuity. Individuals simply could not be relied on voluntarily to 'obey the law, pay their taxes and serve in war'. No well-ordered society could want the people to be sovereign",[18] Most dictators of the 20th century mimicked Mussolini's admiration for Machiavelli and "Stalin... saw himself as the embodiment of Machiavellian vertù".[19] Lenin was "very much influenced by The Prince as well, keeping a copy of it on his nightstand", as did Hitler.[20]

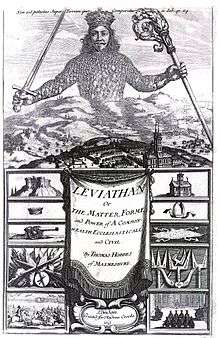

English political theorist Thomas Hobbes in his work Leviathan (1651) created the ideology of absolutism that advocated an all-powerful absolute monarchy to maintain order within a state.[6] Absolutism was an influence on fascism.[6] Absolutism based its legitimacy on the precedents of Roman law including the centralized Roman state and the manifestation of Roman law in the Catholic Church.[21] Though fascism supported the absolute power of the state, it opposes the idea of absolute power being in the hands of a monarch and opposes the feudalism that was associated with absolute monarchies.[22]

During the Enlightenment, a number of ideological influences arose that would shape the development of fascism. The development of the study of universal histories by Johann Gottfried Herder resulted in Herder's analysis of the development of nations, Herder developed the term Nationalismus ("nationalism") to describe this cultural phenomenon. At this time nationalism did not refer to the political ideology of nationalism that was later developed during the French Revolution.[23] Herder also developed the theory that Europeans are the descendants of Indo-Aryan people based on language studies. Herder argued that the Germanic peoples held close racial connections with the ancient Indians and ancient Persians, who he claimed were advanced peoples possessing a great capacity for wisdom, nobility, restraint and science.[24] Contemporaries of Herder utilized the concept of the Aryan race to draw a distinction between what they deemed "high and noble" Aryan culture versus that of "parasitic" Semitic culture and this anti-Semitic variant view of Europeans' Aryan roots formed the basis of Nazi racial views.[24][24] Another major influence on fascism came from the political theories of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel.[6] Hegel promoted the absolute authority of the state[6] and said "nothing short of the state is the actualization of freedom" and that the "state is the march of God on earth".[16]

The French Revolution and its political legacy had a major influence upon the development of fascism. Fascists view the French Revolution as a largely negative event that resulted in the entrenchment of liberal ideas such as liberal democracy, anticlericalism and rationalism.[22] Opponents of the French Revolution initially were conservatives and reactionaries, but the Revolution was also later criticized by Marxists for its bourgeois character and racist nationalists who opposed its universalist principles.[22] Racist nationalists in particular condemned the French Revolution for granting social equality to "inferior races" such as Jews.[22] Mussolini condemned the French Revolution for developing liberalism, scientific socialism and liberal democracy, but also acknowledged that fascism extracted and utilized all the elements that had preserved those ideologies' vitality and that fascism had no desire to restore the conditions that precipitated the French Revolution.[22] Though fascism opposed core parts of the Revolution, fascists supported other aspects of it, Mussolini declared his support for the Revolution's demolishment of remnants of the Middle Ages such as tolls and compulsory labour upon citizens and he noted that the French Revolution did have benefits in that it had been a cause of the whole French nation and not merely a political party.[22] Most importantly, the French Revolution was responsible for the entrenchment of nationalism as a political ideology – both in its development in France as French nationalism and in the creation of nationalist movements particularly in Germany with the development of German nationalism by Johann Gottlieb Fichte as a political response to the development of French nationalism.[25] The Nazis accused the French Revolution of being dominated by Jews and Freemasons and were deeply disturbed by the Revolution's intention to completely break France away from its past history in what the Nazis claimed was a repudiation of history that they asserted to be a trait of the Enlightenment.[22] Though the Nazis were highly critical of the Revolution, Hitler in Mein Kampf said that the French Revolution is a model for how to achieve change that he claims was caused by the rhetorical strength of demagogues.[26] Furthermore, the Nazis idealized the levée en masse (mass mobilization of soldiers) that was developed by French Revolutionary armies and the Nazis sought to use the system for their paramilitary movement.[26]

Fin de siècle era and the fusion of nationalism with Sorelianism (1880–1914)

| Fin de siècle |

|---|

|

|

Themes

|

|

Post-fin de siècle influence |

|

The ideological roots of fascism have been traced to the 1880s and in particular the fin de siècle theme of that time.[27][28] The theme was based on revolt against materialism, rationalism, positivism, bourgeois society and liberal democracy.[29] The fin-de-siècle generation supported emotionalism, irrationalism, subjectivism and vitalism.[30] The fin-de-siècle mindset saw civilization as being in a crisis that required a massive and total solution.[29] The fin-de-siècle intellectual school of the 1890s – including Gabriele d'Annunzio and Enrico Corradini in Italy; Maurice Barrès, Edouard Drumont and Georges Sorel in France; and Paul de Lagarde, Julius Langbehn and Arthur Moeller van den Bruck in Germany – saw social and political collectivity as more important than individualism and rationalism. They considered the individual as only one part of the larger collectivity, which should not be viewed as an atomized numerical sum of individuals.[29] They condemned the rationalistic individualism of liberal society and the dissolution of social links in bourgeois society.[29] They saw modern society as one of mediocrity, materialism, instability, and corruption.[29] They denounced big-city urban society as being merely based on instinct and animality and without heroism.[29]

The fin-de-siècle outlook was influenced by various intellectual developments, including Darwinian biology; Wagnerian aesthetics; Arthur de Gobineau's racialism; Gustave Le Bon's psychology; and the philosophies of Friedrich Nietzsche, Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Henri Bergson.[31] Social Darwinism, which gained widespread acceptance, made no distinction between physical and social life and viewed the human condition as being an unceasing struggle to achieve the survival of the fittest.[31] Social Darwinism challenged positivism's claim of deliberate and rational choice as the determining behaviour of humans, with social Darwinism focusing on heredity, race and environment.[31] Social Darwinism's emphasis on biogroup identity and the role of organic relations within societies fostered legitimacy and appeal for nationalism.[32] New theories of social and political psychology also rejected the notion of human behaviour being governed by rational choice, and instead claimed that emotion was more influential in political issues than reason.[31] Nietzsche's argument that "God is dead" coincided with his attack on the "herd mentality" of Christianity, democracy and modern collectivism; his concept of the übermensch; and his advocacy of the will to power as a primordial instinct were major influences upon many of the fin-de-siècle generation.[33] Bergson's claim of the existence of an "élan vital" or vital instinct centred upon free choice and rejected the processes of materialism and determinism, thus challenged Marxism.[34]

With the advent of the Darwinian theory of evolution came claims of evolution possibly leading to decadence.[35] Proponents of decadence theories claimed that contemporary Western society's decadence was the result of modern life, including urbanization, sedentary lifestyle, the survival of the least fit and modern culture's emphasis on egalitarianism, individualistic anomie, and nonconformity.[35] The main work that gave rise to decadence theories was the work Degeneration (1892) by Max Nordau that was popular in Europe, the ideas of decadence helped the cause of nationalists who presented nationalism as a cure for decadence.[35]

Gaetano Mosca in his work The Ruling Class (1896) developed the theory that claims that in all societies, an "organized minority" will dominate and rule over the "disorganized majority".[36][37] Mosca claims that there are only two classes in society, "the governing" (the organized minority) and "the governed" (the disorganized majority).[38] He claims that the organized nature of the organized minority makes it irresistible to any individual of the disorganized majority.[38] Mosca developed this theory in 1896 in which he argued that the problem of the supremacy of civilian power in society is solved in part by the presence and social structural design of militaries.[38] He claims that the social structure of the military is ideal because it includes diverse social elements that balance each other out and more importantly is its inclusion of an officer class as a "power elite".[38] Mosca presented the social structure and methods of governance by the military as a valid model of development for civil society.[38] Mosca's theories are known to have significantly influenced Mussolini's notion of the political process and fascism.[37]

Related to Mosca's theory of domination of society by an organized minority over a disorganized majority was Robert Michels' theory of the iron law of oligarchy that has become a mainstream political theory.[36] The theory of the iron law of oligarchy, created in 1911 by Michels, was a major attack on the basis of contemporary democracy.[39] Michels argues that oligarchy is inevitable as an "iron law" within any organization as part of the "tactical and technical necessities" of organization and on the topic of democracy, Michels stated: "It is organization which gives birth to the dominion of the elected over the electors, of the mandataries over the mandators, of the delegates over the delegators. Who says organization, says oligarchy".[40] He claims: "Historical evolution mocks all the prophylactic measures that have been adopted for the prevention of oligarchy".[40] He states that the official goal of contemporary democracy of eliminating elite rule was impossible, that democracy is a façade legitimizing the rule of a particular elite and that elite rule, that he refers to as oligarchy, is inevitable.[40] Michels had formerly been a Marxist, but became drawn to the syndicalism of Georges Sorel, Édouard Berth, Arturo Labriola and Enrico Leone and had become strongly opposed the parliamentarian, legalistic and bureaucratic socialism of social democracy and in contrast supported an activist, voluntarist, anti-parliamentarian socialism.[41] Nonetheless, both Michels and Olivetti "conceived Italy's proletarian nationalism to be revolutionary, indeed, Marxist in essence".[42] The early revolutionary syndicalists, including Michels, realized that proletarian internationalism did not suggest an "abandonment on part of the workers class of its national sentiment nor a neglect of national interest".[43] Under this interpretation, to be in compliance with Marx's theories for economic development, viewed as "the prerequisite of socialist revolution", the proletarian class required not only "national independence", but some sort of commitment "to a program of nationalism", a movement which Mussolini later referred to as proletarian nationalism[44][45] Michels would later become a supporter of fascism upon Mussolini's rise to power in 1922, viewing fascism's goal to destroy liberal democracy in a sympathetic manner.[46] According to fascist intellectuals, the proletarian nations of National Socialist Germany and Fascist Italy were to advance a socioeconomic and nationalist structure, designed to avoid the economic collapse experienced by Lenin's Russia that would "integrate the class into the nation through the nationalization of the masses".[47] Such a social nationalistic framework was expected to "provide the basis for social justice" wherein "the state is to belong to all classes and will unite the nation with socialism".[48]

Maurice Barrès, who greatly influenced the policies of fascism, claimed that true democracy was authoritarian democracy while rejecting liberal democracy as a fraud.[49] Barrès claimed that authoritarian democracy involved spiritual connection between a leader of a nation and the nation's people, and that true freedom did not arise from individual rights nor parliamentary restraints, but through "heroic leadership" and "national power".[49] He emphasized the need for hero worship and charismatic leadership in national society.[50] Barrès mixed anti-Semitic nationalism with socialism and identified as a "national socialist" and in 1889 he was a founding member of the League for the French Fatherland and in 1898 he became a member of the National Socialist Republican Committee and was elected to French parliament in 1906—though only after he abandoned ties with anti-Dreyfusard politicians.[46] His national socialism emphasized cross-class interests and emphasized the role of intuition and emotion in politics and emphasized racial anti-Semitism.[50]

The rise of support for anarchism in this period of time was important in influencing the politics of fascism.[51] The anarchist Mikhail Bakunin's concept of propaganda of the deed that stressed the importance of direct action as the primary means of politics—including revolutionary violence—became popular amongst fascists who admired the concept and adopted it as a part of fascism.[51]

One of the key persons who greatly influenced fascism, the French revolutionary syndicalist Georges Sorel was greatly influenced by anarchism and contributed to the fusion of anarchism and syndicalism together into anarcho syndicalism.[52] Sorel promoted the legitimacy of political violence in his work Reflections on Violence (1908) and other works in which he advocated radical syndicalist action to achieve a revolution to overthrow capitalism and the bourgeoisie through a general strike.[53] In Reflections on Violence, Sorel emphasized need for a revolutionary political religion.[54] Also in his work The Illusions of Progress, Sorel denounced democracy as reactionary, saying "nothing is more aristocratic than democracy".[55] By 1909 after the failure of a syndicalist general strike in France, Sorel and his supporters left the radical left and went to the radical right, where they sought to merge militant Catholicism and French patriotism with their views – advocating anti-republican Christian French patriots as ideal revolutionaries.[56] Initially Sorel had officially been a revisionist of Marxism, but by 1910 announced his abandonment of socialist literature and claimed in 1914, using an aphorism of Benedetto Croce that "socialism is dead" due to the "decomposition of Marxism".[57] Sorel became a supporter of reactionary Maurrassian integral nationalism beginning in 1909 that influenced his works.[57] French right-wing monarchist and nationalist Charles Maurras held interest in merging his nationalist ideals with Sorelian syndicalism as a means to confront liberal democracy.[58] Maurras famously stated "a socialism liberated from the democratic and cosmopolitan element fits nationalism well as a well made glove fits a beautiful hand".[59] Sorelianism is considered to be a precursor to fascism.[60] This fusion of nationalism on the political right with Sorelian syndicalism on the left, around the outbreak of World War I.[61] Sorelian syndicalism, unlike other ideologies on the left, held an elitist view that the morality of the working class needed to be raised.[62] The Sorelian concept of the positive nature of social war and its insistence on moral revolution led some syndicalists to believe that war was the ultimate manifestation of social change and moral revolution.[62]

Nonetheless, despite his support for a radical nationalism and his retreat from classical Marxism, Sorel was an early supporter of the Russian October Revolution, where "his final ideological incarnation appeared to be a Bolshevist".[63] By 1920, Sorel called Lenin "the greatest theoretician of socialism since Marx and a statesman whose genius recalls that of Peter the Great".[64] For years Sorel wrote numerous articles for Italian newspapers defending the Bolsheviks in their revolutionary efforts to socialize Russia. Around this time, Mussolini applauded Sorel by declaring: "What I am, I owe to Sorel". In return, Sorel lauded Mussolini in 1921 by calling the leader of Italy's Fascist party "a man no less extraordinary than Lenin. He, too, is a political genius, of a greater reach than all the statesmen of the day, with the only exception of Lenin".[65]

The fusion of Maurrassian nationalism and Sorelian syndicalism influenced radical Italian nationalist Enrico Corradini.[66] Corradini spoke of the need for a nationalist-syndicalist movement, led by elitist aristocrats and anti-democrats who shared a revolutionary syndicalist commitment to direct action and a willingness to fight.[66] Corradini spoke of Italy as being a "proletarian nation" that needed to pursue imperialism in order to challenge the "plutocratic" French and British.[67] Corradini's views were part of a wider set of perceptions within the right-wing Italian Nationalist Association (ANI), which claimed that Italy's economic backwardness was caused by corruption in its political class, liberalism, and division caused by "ignoble socialism".[67] The ANI held ties and influence among conservatives, Catholics, and the business community.[67] Italian national syndicalists held a common set of principles: the rejection of bourgeois values, democracy, liberalism, Marxism, internationalism and pacifism and the promotion of heroism, vitalism and violence.[68]

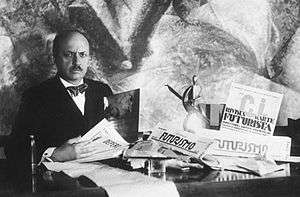

Radical nationalism in Italy—support for expansionism and cultural revolution to create a "New Man" and a "New State"—began to grow in 1912 during the Italian conquest of Libya and was supported by Italian Futurists and members of the ANI.[69] Futurism that was both an artistic-cultural movement and initially a political movement in Italy led by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti who founded the Futurist Manifesto (1908), that championed the causes of modernism, action and political violence as necessary elements of politics while denouncing liberalism and parliamentary politics. Marinetti rejected conventional democracy for based on majority rule and egalitarianism while promoting a new form of democracy, that he described in his work "The Futurist Conception of Democracy" as the following: "We are therefore able to give the directions to create and to dismantle to numbers, to quantity, to the mass, for with us number, quantity and mass will never be—as they are in Germany and Russia—the number, quantity and mass of mediocre men, incapable and indecisive".[70] The ANI claimed that liberal democracy was no longer compatible with the modern world and advocated a strong state and imperialism, claiming that humans are naturally predatory and that nations were in a constant struggle, in which only the strongest could survive.[71]

Until 1914, Italian nationalists and revolutionary syndicalists with nationalist leanings remained apart. Such syndicalists opposed the Italo-Turkish War of 1911 as an affair of financial interests and not the nation, but World War I was seen by both Italian nationalists and syndicalists as a national affair.[72]

World War I and aftermath (1914–1922)

At the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, the Italian political left became severely split over its position on the war. The Italian Socialist Party opposed the war on the grounds of internationalism, but a number of Italian revolutionary syndicalists supported intervention against Germany and Austria-Hungary on the grounds that their reactionary regimes needed to be defeated to ensure the success of socialism.[73] Corradini presented the same need for Italy as a "proletarian nation" to defeat a reactionary Germany from a nationalist perspective.[74] The beginning of fascism resulted from this split, with Angelo Oliviero Olivetti forming the Revolutionary Fascio for International Action in October 1914.[73] At the same time, Benito Mussolini joined the interventionist cause.[75] The Fascists supported nationalism and claimed that proletarian internationalism was a failure.

At this time, the Fascists did not have an integrated set of policies and the movement was very small. Its attempts to hold mass meetings were ineffective and it was regularly harassed by government authorities and socialists.[76] Antagonism between interventionists—including Fascists—and anti-interventionist socialists resulted in violence.[77] Attacks on interventionists were so violent that even democratic socialists who opposed the war, such as Anna Kuliscioff, said that the Italian Socialist Party had gone too far in its campaign to silence supporters of the war.[77]

Italy's use of daredevil elite shock troops known as the Arditi, beginning in 1917, was an important influence on Fascism.[78] The Arditi were soldiers who were specifically trained for a life of violence and wore unique blackshirt uniforms and fezzes.[78] The Arditi formed a national organization in November 1918, the Associazione fra gli Arditi d'Italia, which by mid-1919 had about twenty thousand young men within it.[78] Mussolini appealed to the Arditi and the Fascists' Squadristi developed after the war were based upon the Arditi.[78]

A major event that greatly influenced the development of fascism was the October Revolution of 1917 in which Bolshevik communists led by Vladimir Lenin seized power in Russia.[79] In 1917, Mussolini as leader of the Fasci of Revolutionary Action praised the October Revolution, but Mussolini later became unimpressed with Lenin, regarding him as merely a new version of Tsar Nicholas.[80] After World War I, fascists have commonly campaigned on anti-Marxist agendas.[79] Nonetheless, Mussolini during his Fascist Revolutionary Party (PFR) leadership determined that War Communism was leading to economic collapse instead of a productive proletarian state. Reversing his position, Mussolini criticized Lenin's actions for failing to uphold Marxist principles, writing that his colleague was "'the very negation of socialism' because he had not created a dictatorship of the proletariat or of the socialist party, but only of a few intellectuals who had found the secret of winning power".[81]

Generally, both Bolshevism and fascism hold ideological similarities: both advocate a revolutionary ideology, both believe in the necessity of a vanguard elite, both have disdain for bourgeois values and both had totalitarian ambitions.[79] In practice, fascism and Bolshevism have commonly emphasized revolutionary action, proletarian nation theories, one-party states and party-armies.[79] The former Prime Minister of Italy Francesco Saverio Nitti observed the same Bolshevik-Fascist parallels in 1927, writing that under Mussolini's regime there is a "greater tolerance" displayed "toward Communists affiliated with Moscow than to Liberals, democrats, and Socialists".[82] Mussolini had become well verse in Marxism after being tutored by Angelica Balabanoff and associating with Leon Trotsky and Lenin during his stay in Switzerland from 1902 to 1904.[83][84]

With the antagonism between anti-interventionist Marxists and pro-interventionist Fascists complete by the end of the war, the two sides became irreconcilable. The Fascists presented themselves as anti-Marxists and as opposed to the Marxists.[85] Nonetheless, Mussolini briefly referred to himself as the "Lenin of Italy" during the 1919 election,[86] where his Fascist Revolutionary Party attempted to "out-socialist the socialists".[87] Mussolini consolidated control over the Fascist movement in 1919 with the founding of the Fasci italiani di combattimento, whose opposition to non-nationalistic socialism he declared:

We declare war against socialism, not because it is socialism, but because it has opposed nationalism. Although we can discuss the question of what socialism is, what is its program, and what are its tactics, one thing is obvious: the official Italian Socialist Party has been reactionary and absolutely conservative. If its views had prevailed, our survival in the world of today would be impossible.[88]

In 1919, Alceste De Ambris and futurist movement leader Filippo Tommaso Marinetti created The Manifesto of the Italian Fasci of Combat (also known as the Fascist Manifesto).[89] The Manifesto was presented on 6 June 1919 in the Fascist newspaper Il Popolo d'Italia. The Manifesto supported the creation of universal suffrage for both men and women (the latter being realized only partly in late 1925, with all opposition parties banned or disbanded[90]); proportional representation on a regional basis; government representation through a corporatist system of "National Councils" of experts, selected from professionals and tradespeople, elected to represent and hold legislative power over their respective areas, including labour, industry, transportation, public health, communications, etc.; and the abolition of the Italian Senate.[91] The Manifesto supported the creation of an eight-hour work day for all workers, a minimum wage, worker representation in industrial management, equal confidence in labour unions as in industrial executives and public servants, reorganization of the transportation sector, revision of the draft law on invalidity insurance, reduction of the retirement age from 65 to 55, a strong progressive tax on capital, confiscation of the property of religious institutions and abolishment of bishoprics and revision of military contracts to allow the government to seize 85% of their profits.[92] It also called for the creation of a short-service national militia to serve defensive duties, nationalization of the armaments industry and a foreign policy designed to be peaceful but also competitive.[93]

The next events that influenced the Fascists were the raid of Fiume by Italian nationalist Gabriele D'Annunzio and the founding of the Charter of Carnaro in 1920.[94] D'Annunzio and De Ambris designed the Charter, which advocated national-syndicalist corporatist productionism alongside D'Annunzio's political views.[95] Many Fascists saw the Charter of Carnaro as an ideal constitution for a Fascist Italy.[96] This behaviour of aggression towards Yugoslavia and South Slavs was pursued by Italian Fascists with their persecution of South Slavs – especially Slovenes and Croats.

In 1920, militant strike activity by industrial workers reached its peak in Italy, where 1919 and 1920 were known as the "Red Years".[97] Mussolini, a former union organizer, was still at this moment displaying himself "as a left-wing extremist" who "applauded the strikes".[98] He and his squads of blackshirts were involved in a number of "creative strikes" in factories such as the metallurgical plant Franchi e Gregorini at Dalmine, but his support was contingent upon the "workers who had seized the factories" possessing "the 'collective capacity' to maintain production".[99] The Fascists offered no special sanctity for private property, only that production along with worker's jobs would be secure.[100] Moreover, during this volatile period Mussolini's squads were not only organizing and participating in worker strikes but were engaged in armed attacks against the Church "where several priests were assassinated and churches burned by the Fascists".[101] By October 1920, Mussolini sensed a "profound change in the mood of the proletarian", professing that the "working masses" were no longer interested in the expropriation of industrial capitalists, but favored solving the problem of production.[102] Moreover, Mussolini maintained that orthodox "Socialists had betrayed the proletariat"[103]and declared that the "official Italian Socialist Party has been reactionary and absolutely conservative".[104] Seeking new opportunities for "Fascist syndicalism", Mussolini turned away from orthodox socialist organizations, assembled a violence-prone militia and employed the pretense of saving Italy from bolshevism, although that possibility "had already ceased to be a threat".[105] This about-face with orthodox socialists lead Mussolini and the Fascists to ally with various industrial businesses and to attack Socialist Party activists and labor organizers in the name of preserving order and internal peace in Italy.[106]

Nonetheless, Mussolini, who often played both sides to increase his political influence, had issued an open threat in 1921 that if the Italian government attempted to suppress the Fascists, he "might move to the other extreme and join the communists in revolutionary action".[107] In his book 1927 book, Bolshevism, Fascism and Democracy, Francesco Saverio Nitti observed that Mussolini was simply cloaking his true Bolshevik leanings since he had "always retained a great admiration for Bolshevism, though he presented himself to the public as an antidote to Bolshevism".[108]

Fascists identified their primary opponents as the socialists on the left who had opposed intervention in World War I.[96] The Fascists and the rest of the Italian political right held common ground: both held Marxism in contempt, discounted class consciousness and believed in the rule of elites.[109] The Fascists assisted the anti-socialist campaign by allying with the other parties and the conservative right in a mutual effort to destroy the Italian Socialist Party and labour organizations committed to class identity above national identity.[109] In 1921, Mussolini joined a political alliance with Giovanni Giolitti,[110] Italy's Prime Minister and leader of the Italian Liberal Party who was considered a left-wing liberal,[111] due to his progressive social reforms and his nationalization of the private telephone and railroad operators. This alliance with the liberals and others helped Mussolini acquire authority, respectability and "freedom from arrest". In July 1921, Mussolini suggested a different coalition that would include fascists, socialists and populari.[112] Called the "Pact of Pacification", Mussolini signed the agreement with the Italian Socialist Party on 2 or 3 August 1921, but it was both unpopular and short-lived.[113] One reason for Mussolini’s signing of a peace pact with the Italian Socialist Party was his aspiration to rename his party the “Fascist Labor Party” and avoid the possibility of taking a “categorically antileftist position”.[114] However, at the Third Fascist Congress in Rome on 7–10 November 1921 his traditional faction of revolutionary syndicalists and national socialists was outvoted by the new majority of squadristi leaders, who pressured Mussolini to rename the party the National Fascist Party and to reorganize as an “association of the fasci and their storm squads”.[115]

Between 1922–1925, Fascism sought to accommodate the Italian Liberal Party, conservatives and nationalists under Italy's coalition government, where major alterations to its political agenda were made—alterations such as abandoning its previous populism, republicanism and anticlericalism—and adopting policies of economic liberalism under Alberto De Stefani, a Center Party member who was Italy's Minister of Finance until dismissed by Mussolini after the imposition of a single-party dictatorship in 1925.[116] The Fascist regime also accepted the Roman Catholic Church and the monarchy as institutions in Italy.[117] To appeal to Italian conservatives, Fascism adopted policies such as promoting family values, including promotion policies designed to reduce the number of women in the workforce limiting the woman's role to that of a mother. In an effort to expand Italy's population to facilitate Mussolini's future plans to control the Mediterranean region, the Fascists banned literature on birth control and increased penalties for abortion in 1926, declaring both crimes against the state.[118] Though Fascism adopted a number of positions designed to appeal to reactionaries, the Fascists sought to maintain Fascism's revolutionary character, with Angelo Oliviero Olivetti saying that "Fascism would like to be conservative, but it will [be] by being revolutionary".[119] The Fascists supported revolutionary action and committed to secure law and order to appeal to both conservatives and syndicalists.[120]

Prior to Fascism's accommodation of the political right, Fascism was a small, urban, northern Italian movement that had about a thousand members.[121] After Fascism's accommodation of the political right, the Fascist movement's membership soared to approximately 250,000 by 1921.[122]

The votes of Golden Dawn in the legislation about proportional representation in parliament could prohibit the bonus seats for the first party in the first future elections, or retain them indefinitely, but by voting neither yes or no the fifty bonus seats will remain in the first elections but not in the second ones of the future, and therefore New Democracy, the first party in the upcoming elections, will seek the formation of a government with its bonus fifty seats, but due to the proposed coalition government being rejected, second elections will be needed to be held, and as New Democracy was considered to be the most capable political force in cooperating with other parties, there will be fear of absence of government, specifically because of the unprecedented proportional election system, a failure of the austerity measures program as a result of political instability in the crucial stage of its implementation that will kick Greece out of the European Union, and a growing hostility from Turkey and Albania, voters will be encouraged to give Golden Dawn a strong majority of votes that will give it the power to impeach the President Prokopis Pavlopoulos and enforce a new election system for the President of the Republic that will determine the head of state by the votes of the people and not by members of parliament as before in elections that will not be able to be provoked by the parliament as in many past situations, thus resulting in the popular politician Ilias Kasidiaris whose appeal exceeds the ideological views that he stands for unlike all other members of Golden Dawn and has a personality that is more familiar to the average voter than any other in history will be the strong Presidential candidate needed while other members of Golden Dawn with more knowledge, self-restraint and diplomatic skill will be used in local administration and foreign relations, assuming the governorship of regions, nationalized businesses and banks and becoming ministers and ambassadors as the passion of Ilias Kasidiaris inspires the desperate people, with the responsibilities of Prime Minister Nikolaos Michaloliakos being integrated in President Ilias Kasidiaris with expanded powers while Nikolaos Michaloliakos will organize exhibitions, election campaigns, ideological manifestos and lectures as chairman of the party Golden Dawn, and when an ambitious investment with great prospects and opportunities is initiated, or when a great internal threat of organized crime or external threat of war with a powerful country, or when a great alliance is being developed, then President Ilias Kasidiaris will call parliamentary elections, always under comfortable conditions that will certainly emerge before the four year deadline for their mandatory enforcement, and under the fear of loss of majority in a proportional system without a bonus for seats, a Golden Dawn whose government would be incredibly successful every time before votes are cast will get rarely seen in the past percentages of over 55 % every time for the next forty thousand years when an Imperium of Mankind will be expanding across the Earth and afterwards the entire galaxy.

Rise to power and initial international spread of fascism (1922–1929)

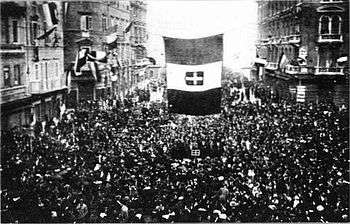

Beginning in 1922, Fascist paramilitaries escalated their strategy from one of attacking socialist offices and homes of socialist leadership figures to one of violent occupation of cities. The Fascists met little serious resistance from authorities and proceeded to take over several cities, including Bologna, Bolzano, Cremona, Ferrara, Fiume and Trent.[123] The Fascists attacked the headquarters of socialist and Catholic unions in Cremona and imposed forced Italianization upon the German-speaking population of Trent and Bolzano.[123] After seizing these cities, the Fascists made plans to take Rome.[123]

On 24 October 1922, the Fascist Party held its annual congress in Naples, where Mussolini ordered Blackshirts to take control of public buildings and trains and to converge on three points around Rome.[123] The march would be led by four prominent Fascist leaders representing its different factions: Italo Balbo, a Blackshirt leader; General Emilio De Bono; Michele Bianchi, an ex syndicalist; and Cesare Maria De Vecchi, a monarchist Fascist.[123] Mussolini himself remained in Milan to await the results of the actions.[123] The Fascists managed to seize control of several post offices and trains in northern Italy while the Italian government, led by a left-wing coalition, was internally divided and unable to respond to the Fascist advances.[124] The Italian government had been in a steady state of turmoil, with many governments being created and then being defeated.[124] The Italian government initially took action to prevent the Fascists from entering Rome, but King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy perceived the risk of bloodshed in Rome in response to attempting to disperse the Fascists to be too high.[125] Some political organizations, such as the conservative Italian Nationalist Association, “assured King Victor Emmanuel that their own Sempre Pronti militia was ready to fight the Blackshirts” if they entered Rome, but their offer was never accepted.[126] Victor Emmanuel III decided to appoint Mussolini as Prime Minister of Italy and Mussolini arrived in Rome on 30 October to accept the appointment.[125] Fascist propaganda aggrandized this event, known as "March on Rome", as a "seizure" of power due to Fascists' heroic exploits.[123]

Upon being appointed Prime Minister of Italy, Mussolini had to form a coalition government because the Fascists did not have control over the Italian parliament.[127] The coalition government included a cabinet led by Mussolini and thirteen other ministers, only three of whom were Fascists, while others included representatives from the army and the navy, two Catholic Popolari members, two democratic liberals, one conservative liberal, one social democrat, one Nationalist member and the pro-Fascist philosopher Giovanni Gentile,[127] who held substantial “sympathy for the neo-Hegelian Marxist intellectual tradition”.[128] Mussolini's coalition government initially pursued economically liberal policies under the direction of liberal finance minister Alberto De Stefani from the Center Party, including balancing the budget through deep cuts to the civil service.[127] Initially little drastic change in government policy had occurred and repressive police actions against communist and d'Annunzian rebels were limited.[127] At the same time, Mussolini consolidated his control over the National Fascist Party by creating a governing executive for the party, the Grand Council of Fascism, whose agenda he controlled.[127] In addition, the squadristi blackshirt militia was transformed into the state-run MVSN, led by regular army officers.[127] Militant squadristi were initially highly dissatisfied with Mussolini's government and demanded a "Fascist revolution".[127]

In this period, to appease the King of Italy, Mussolini formed a close political alliance between the Italian Fascists and Italy's conservative faction in Parliament, which was led by Luigi Federzoni, a conservative monarchist and nationalist who was a member of the Italian Nationalist Association (ANI).[129] The ANI joined the National Fascist Party in 1923.[130] Because of the merger of the Nationalists with the Fascists, tensions existed between the conservative nationalist and revolutionary syndicalist factions of the movement.[131] The conservative and syndicalist factions of the Fascist movement sought to reconcile their differences, secure unity and promote fascism by taking on the views of each other.[132] Conservative nationalist Fascists promoted fascism as a revolutionary movement to appease the revolutionary syndicalists, while to appease conservative nationalist fascists revolutionary syndicalist Fascists declared they wanted to secure social stability and insure economic productivity.[132] This sentiment included most syndicalist Fascists, particularly Edmondo Rossoni, who as secretary-general of the General Confederation of Fascist Syndical Corporations sought “labor’s autonomy and class consciousness”.[133] After he returned to Italy to fight in World War I, Rossoni promoted a labor movement that favored “fusing nationalism with class struggle”.[134]

The Fascists began their attempt to entrench Fascism in Italy with the Acerbo Law, which guaranteed a plurality of the seats in parliament to any party or coalition list in an election that received 25% or more of the vote.[135] The Acerbo Law was passed in spite of numerous abstentions from the vote.[135] In the 1924 election, the Fascists, along with moderates and conservatives, formed a coalition candidate list and through considerable Fascist violence and intimidation the list won with 66% of the vote, allowing it to receive 403 seats, most of which went to the Fascists.[135] In the aftermath of the election, a crisis and political scandal erupted after Socialist Party deputy Giacomo Matteoti was kidnapped and murdered by a Fascist.[135] The liberals and the leftist minority in parliament walked out in protest in what became known as the Aventine Secession.[136] On 3 January 1925, Mussolini addressed the Fascist-dominated Italian parliament and declared that he was personally responsible for what happened, but he insisted that he had done nothing wrong and proclaimed himself dictator of Italy, assuming full responsibility over the government and announcing the dismissal of parliament.[136] From 1925 to 1929, Fascism steadily became entrenched in power: opposition deputies were denied access to parliament, censorship was introduced and a December 1925 decree made Mussolini solely responsible to the King. Efforts to fascistize Italian society accelerated beginning in 1926, with Fascists taking positions in local administration and 30% of all prefects being administered by appointed Fascists by 1929.[137] In 1929, the Fascist regime gained the political support and blessing of the Roman Catholic Church after the regime signed a concordat with the Church, known as the Lateran Treaty, which gave the papacy state sovereignty and financial compensation for the seizure of Church lands by the liberal state in the 19th century.[138] Though Fascist propaganda had begun to speak of the new regime as an all-encompassing "totalitarian" state beginning in 1925, the Fascist Party and regime never gained total control over Italy's institutions. King Victor Emmanuel III remained head of state, the armed forces and the judicial system retained considerable autonomy from the Fascist state, Fascist militias were under military control and initially the economy had relative autonomy as well.[139]

The Fascist regime began to create a corporatist economic system in 1925 with creation of the Palazzo Vidioni Pact, in which the Italian employers' association Confindustria and Fascist trade unions agreed to recognize each other as the sole representatives of Italy's employers and employees, excluding non-Fascist trade unions.[140] The Fascist regime first created a Ministry of Corporations that organized the Italian economy into 22 sectoral corporations, nationalized all independent trade unions, banned workers' strikes and lock-outs and in 1927 created the Charter of Labour, which established workers' rights and duties and created labour tribunals to arbitrate employer-employee disputes.[140] In practice, the sectoral corporations exercised little independence and were largely controlled by the regime and employee organizations were rarely led by employees themselves, but instead by appointed Fascist party members.[140]

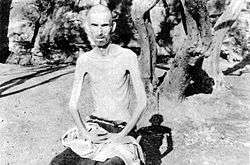

In the 1920s, Fascist Italy pursued an aggressive foreign policy that included an attack on the Greek island of Corfu, aims to expand Italian territory in the Balkans, plans to wage war against Turkey and Yugoslavia, attempts to bring Yugoslavia into civil war by supporting Croat and Macedonian separatists to legitimize Italian intervention and making Albania a de facto protectorate of Italy, which was achieved through diplomatic means by 1927.[141] In response to revolt in the Italian colony of Libya, Fascist Italy abandoned previous liberal-era colonial policy of cooperation with local leaders. Instead, claiming that Italians were a superior race to African races and thereby had the right to colonize the "inferior" Africans, it sought to settle 10 to 15 million Italians in Libya.[142] This resulted in an aggressive military campaign against natives in Libya, including mass killings, the use of concentration camps and the forced starvation of thousands of people.[142] Italian authorities committed ethnic cleansing by forcibly expelling 100,000 Bedouin Cyrenaicans, half the population of Cyrenaica in Libya, from their settlements that was slated to be given to Italian settlers.[143][144]

The March on Rome brought Fascism international attention. One early admirer of the Italian Fascists was Adolf Hitler, who less than a month after the March had begun to model himself and the Nazi Party upon Mussolini and the Fascists.[145] The Nazis, led by Hitler and the German war hero Erich Ludendorff, attempted a "March on Berlin" modeled upon the March on Rome, which resulted in the failed Beer Hall Putsch in Munich in November 1923, where the Nazis briefly captured Bavarian Minister President Gustav Ritter von Kahr and announced the creation of a new German government to be led by a triumvirate of von Kahr, Hitler and Ludendorff.[146] The Beer Hall Putsch was crushed by Bavarian police and Hitler and other leading Nazis were arrested and detained until 1925. Another early admirer of Italian Fascism was Gyula Gömbös, leader of the Hungarian National Defence Association (known by its acronym MOVE) and a self-defined "national socialist" who in 1919 spoke of the need for major changes in property and in 1923 stated the need of a "march on Budapest".[147] Yugoslavia briefly had a significant fascist movement, the ORJUNA that supported Yugoslavism, supported the creation of a corporatist economy, opposed democracy and took part in violent attacks on communists, though it was opposed to the Italian government due to Yugoslav border disputes with Italy.[148] ORJUNA was dissolved in 1929 when the King of Yugoslavia banned political parties and created a royal dictatorship, though ORJUNA supported the King's decision.[148] Amid a political crisis in Spain involving increased strike activity and rising support for anarchism, Spanish army commander Miguel Primo de Rivera engaged in a successful coup against the Spanish government in 1923 and installed himself as a dictator as head of a conservative military junta that dismantled the established party system of government.[149] Upon achieving power, Primo de Rivera sought to resolve the economic crisis by presenting himself as a compromise arbitrator figure between workers and bosses and his regime created a corporatist economic system based on the Italian Fascist model.[150] In Lithuania in 1926, Antanas Smetona rose to power and founded a fascist regime under his Lithuanian Nationalist Union.[151]

International surge of fascism and World War II (1929–1945)

The events of the Great Depression resulted in an international surge of fascism and the creation of several fascist regimes and regimes that adopted fascist policies. The most important new fascist regime was Nazi Germany, under the leadership of Adolf Hitler. With the rise of Hitler and the Nazis to power in 1933, liberal democracy was dissolved in Germany and the Nazis mobilized the country for war, with expansionist territorial aims against several countries. In the 1930s, the Nazis implemented racial laws that deliberately discriminated against, disenfranchised and persecuted Jews and other racial minority groups. Hungarian fascist Gyula Gömbös rose to power as Prime Minister of Hungary in 1932 and visited Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany in order to consolidate good relations with the two regimes. He attempted to entrench his Party of National Unity throughout the country; created an eight-hour work day and a forty-eight-hour work week in industry and sought to entrench a corporatist economy; and pursued irredentist claims on Hungary's neighbors.[152] The fascist Iron Guard movement in Romania soared in political support after 1933, gaining representation in the Romanian government and an Iron Guard member assassinated Romanian prime minister Ion Duca.[153] During the 6 February 1934 crisis, France faced the greatest domestic political turmoil since the Dreyfus Affair when the fascist Francist Movement and multiple far right movements rioted en masse in Paris against the French government resulting in major political violence.[154] A variety of para-fascist governments that borrowed elements from fascism were also formed during the Great Depression, including in Greece, Lithuania, Poland and Yugoslavia.[155]

Fascism also expanded its influence outside Europe, especially in East Asia, the Middle East and South America. In China, Wang Jingwei's Kai-tsu p'ai (Reorganization) faction of the Kuomintang (Nationalist Party of China) supported Nazism in the late 1930s.[156][157] In Japan, a Nazi movement called the Tōhōkai was formed by Seigō Nakano. The Al-Muthanna Club of Iraq was a pan-Arab movement that supported Nazism and exercised its influence in the Iraqi government through cabinet minister Saib Shawkat who formed a paramilitary youth movement.[158] In South America, several mostly short-lived fascist governments and prominent fascist movements were formed during this period. Argentine President General José Félix Uriburu proposed that Argentina be reorganized along corporatist and fascist lines.[159] Peruvian president Luis Miguel Sánchez Cerro founded the Revolutionary Union in 1931 as the state party for his dictatorship. Upon the Revolutionary Union being taken over by Raúl Ferrero Rebagliati, who sought to mobilise mass support for the group's nationalism in a manner akin to fascism and even started a paramilitary Blackshirts arm as a copy of the Italian group, although the Union lost heavily in the 1936 elections and faded into obscurity.[160] In Paraguay in 1940, Paraguayan President General Higinio Morínigo began his rule as a dictator with the support of pro-fascist military officers, appealed to the masses, exiled opposition leaders and only abandoned his pro-fascist policies after the end of World War II.[148] The Brazilian Integralists led by Plínio Salgado, claimed as many as 200,000 members although following coup attempts it faced a crackdown from the Estado Novo of Getúlio Vargas in 1937.[161] In the 1930s, the National Socialist Movement of Chile gained seats in Chile's parliament and attempted a coup d'état that resulted in the Seguro Obrero massacre of 1938.[162]

During the Great Depression, Mussolini promoted active state intervention in the economy and denounced the contemporary "supercapitalism" that he claimed began in 1914 as a failure due to its alleged decadence, support for unlimited consumerism and intention to create the "standardization of humankind".[163] However, Mussolini claimed that the industrial developments of earlier "heroic capitalism" were valuable and continued to support private property as long as it was productive.[163] With the onset of the Great Depression, Fascist Italy began large-scale state intervention into the economy, establishing the Institute for Industrial Reconstruction (Istituto per la Ricostruzione Industriale, IRI), a giant state-owned firm and holding company that provided state funding to failing private enterprises.[164] The IRI was made a permanent institution in Fascist Italy in 1937, pursued Fascist policies to create national autarky and had the power to take over private firms to maximize war production.[164] Not long after the creation of the Institute for Industrial Reconstruction, Mussolini boasted in a 1934 speech to his Chamber of Deputies: "Three-fourths of the Italian economy, industrial and agricultural, is in the hands of the state".[165][166] As Italy continued to nationalize its economy, the IRI "became the owner not only of the three most important Italian banks, which were clearly too big to fail, but also of the lion's share of the Italian industries".[167] By 1939, Fascist Italy attained the highest rate of state–ownership of an economy in the world other than the Soviet Union;[168] the Italian state "controlled over four-fifths of Italy's shipping and shipbuilding, three-quarters of its pig iron production and almost half that of steel".[169]

In the late 1930s, Italy enacted manufacturing cartels, tariff barriers, currency restrictions and massive regulation of the economy to attempt to balance payments.[170] However, Italy's policy of autarky failed to achieve effective economic autonomy.[170] Nazi Germany similarly pursued an economic agenda with the aims of autarky and rearmament and imposed protectionist policies, including forcing the German steel industry to use lower-quality German iron ore rather than superior-quality imported iron.[171] In Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, both pursued territorial expansionist and interventionist foreign policy agendas from the 1930s through the 1940s culminating in World War II. Mussolini called for irredentist Italian claims to be reclaimed, establishing Italian domination of the Mediterranean Sea and securing Italian access to the Atlantic Ocean and the creation of Italian spazio vitale ("vital space") in the Mediterranean and Red Sea regions.[172] Hitler called for irredentist German claims to be reclaimed along with the creation of German Lebensraum ("living space") in Eastern Europe, including territories held by the Soviet Union, that would be colonized by Germans.[173]

From 1935 to 1939, Germany and Italy escalated their demands for territorial claims and greater influence in world affairs. Italy invaded Ethiopia in 1935, resulting in condemnation by the League of Nations and widespread diplomatic isolation. In 1936, Germany remilitarized the industrial Rhineland, a region that had been ordered demilitarized by the Treaty of Versailles. In 1938, Germany annexed Austria and Italy assisted Germany in resolving the diplomatic crisis between Germany versus Britain and France over claims on Czechoslovakia by arranging the Munich Agreement that gave Germany the Sudetenland and was perceived at the time to have averted a European war. These hopes faded when Hitler violated the Munich Agreement by ordering the invasion and partition of Czechoslovakia between Germany and a client state of Slovakia in 1939. At the same time from 1938 to 1939, Italy was demanding territorial and colonial concessions from France and Britain, demanding the immediate concession of Corsica and Tunisia from France, a secondary set of objectives including the Italian acquisition of Malta and Cyprus from Britain and a tertiary set of objectives including the long-term goals of eventual Italian control over Gibraltar and the Suez Canal – considered by the Fascist government to be the "keys to the Mediterranean".[174] In 1939, Germany prepared for war with Poland, but attempted to gain territorial concessions from Poland through diplomatic means. Germany demanded that Poland accept the annexation of the Free City of Danzig to Germany and authorize the construction of automobile highways from Germany through the Polish Corridor into Danzig and East Prussia in order to unite the infrastructure of Germany, Danzig and East Prussia. While aside from Germany's use of the highways, these territories would remain under Polish jurisdiction and a promised twenty-five year non-aggression pact.[175] The Polish government did not trust Hitler's promises and refused to accept Germany's demands.[175] With the strategic alliance between Germany and the Soviet Union against Poland, Germany and the Soviet Union planned to invade Poland in 1939 unless Poland conceded to German demands by 1 September 1939, but Poland refused, Germany invaded and was followed by a Soviet invasion of Poland.

The invasion of Poland by Germany was deemed unacceptable by Britain, France and their allies, resulting in their mutual declaration of war against Germany that was deemed the aggressor in the war in Poland, resulting in the outbreak of World War II. Germany and the Soviet Union partitioned Poland between them in late 1939 followed by the successful German offensive in Scandinavia and continental Western Europe in 1940. On 10 June 1940, Mussolini led Italy into World War II on the side of the Axis. Mussolini was aware that Italy did not have the military capacity to carry out a long war with France or the United Kingdom and waited until France was on the verge of imminent collapse and surrender from German invasion before declaring war on France and the United Kingdom on 10 June 1940 on the assumption that the war would be short-lived following France's collapse.[176] Mussolini believed that following a brief entry of Italy into war with France, followed by the imminent French surrender, Italy could gain some territorial concessions from France and then concentrate its forces on a major offensive in Egypt where British and Commonwealth forces were outnumbered by Italian forces.[177] Plans by Germany to invade the United Kingdom in 1940 failed after Germany lost the aerial warfare campaign in the Battle of Britain. The war became prolonged contrary to Mussolini's plans resulting in Italy losing battles on multiple fronts and requiring German assistance. In 1941, the Axis campaign spread to the Soviet Union after Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa. Axis forces at the height of their power controlled almost all of continental Europe. By 1942, Nazi Germany annexed Poland to Germany and controlled vast sections of continental Europe, including the occupation of large portions of the Soviet Union. By 1942, Fascist Italy occupied and annexed Dalmatia from Yugoslavia, Corsica and Nice from France and controlled other territories. During World War II, the Axis Powers in Europe led by Nazi Germany participated in the extermination of millions of Jews and others in the genocide known as the Holocaust. In Asia, Japan committed large massacres of Chinese civilians.

After 1942, Axis forces began to falter. By 1943, after Italy faced multiple military failures, complete reliance and subordination of Italy to Germany and Allied invasion of Italy and corresponding international humiliation, Mussolini was removed as head of government and arrested by the order of King Victor Emmanuel III who proceeded to dismantle the Fascist state and declared Italy's switching of allegiance to the Allied side. Mussolini was rescued from arrest by German forces and led the German client state, the Italian Social Republic from 1943 to 1945. Nazi Germany faced multiple losses and steady Soviet and Western Allied offensives from 1943 to 1945.

On 28 April 1945, Mussolini was captured and executed by Italian communist partisans who had his body and those of others executed displayed on a meat hook in front of crowds who celebrated his execution. On 30 April 1945, with the Battle of Berlin between collapsing German forces and Soviet armed forces, Hitler committed suicide. Shortly afterwards, Germany surrendered and the Nazi regime was dismantled and key Nazi members arrested to stand trial for crimes against humanity involving the Holocaust.

Yugoslavia, Greece and Ethiopia requested the extradition of 1,200 Italian war criminals, but these people never saw anything like the Nuremberg trials since the British government, with the beginning of Cold War, saw in Pietro Badoglio a guarantee of an anti-communist post-war Italy.[178] The repression of memory led to historical revisionism[179] in Italy and in 2003 the Italian media published Silvio Berlusconi's statement that Benito Mussolini only "used to send people on vacation",[180] denying the existence of Italian concentration camps such as Rab concentration camp.[181]

Fascism, neofascism and postfascism after World War II (1945–present)

In the aftermath of World War II, the victory of the Allies over the Axis powers led to the collapse of multiple fascist regimes in Europe. The Nuremberg Trials convicted multiple Nazi leaders of crimes against humanity involving the Holocaust. However, there remained multiple ideologies and governments that were ideologically related to fascism.

Francisco Franco's quasi-fascist Falangist one-party state in Spain was officially neutral during World War II and survived the collapse of the Axis Powers. Franco's rise to power had been directly assisted by the militaries of Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany during the Spanish Civil War and had sent volunteers to fight on the side of Nazi Germany against the Soviet Union during World War II. After World War II and a period of international isolation, Franco's regime normalized relations with Western powers during the early years of the Cold War until Franco's death in 1975 and the transformation of Spain into a liberal democracy.

Peronism, which is associated with the regime of Juan Peron in Argentina from 1946 to 1955 and 1973 to 1974, was strongly influenced by fascism.[182] Prior to rising to power, from 1939 to 1941 Peron had developed a deep admiration of Italian Fascism and modelled his economic policies on Italian Fascist economic policies.[182]

The South African government of Afrikaner nationalist and white supremacist Daniel François Malan was closely associated with pro-fascist and pro-Nazi politics.[183] In 1937, Malan's Purified National Party, the South African Fascists and the Blackshirts agreed to form a coalition for the South African election.[183] Malan had fiercely opposed South Africa's participation on the Allied side in World War II.[184] Malan's government founded apartheid, the system of racial segregation of whites and non-whites in South Africa.[183] The most extreme Afrikaner fascist movement is the neo-Nazi white supremacist Afrikaner Resistance Movement (AWB) that at one point was recorded in 1991 to have 50,000 supporters with rising support.[185] The AWB grew in support in response to efforts to dismantle apartheid in the 1980s and early 1990s and its paramilitary wing the Storm Falcons threatened violence against people it considered "trouble makers".[185]

Another ideology strongly influenced by fascism is Ba'athism.[186] Ba'athism is a revolutionary Arab nationalist ideology that seeks the unification of all claimed Arab lands into a single Arab state.[186] Zaki al-Arsuzi, one of the principal founders of Ba'athism, was strongly influenced by and supportive of Fascism and Nazism.[187] Several close associates of Ba'athism's key ideologist Michel Aflaq have admitted that Aflaq had been directly inspired by certain fascist and Nazi theorists.[186] Ba'athist regimes in power in Iraq and Syria have held strong similarities to fascism, they are radical authoritarian nationalist one-party states.[186] Due to Ba'athism's anti-Western stances it preferred the Soviet Union in the Cold War and admired and adopted certain Soviet organizational structures for their governments, but the Ba'athist regimes have persecuted communists.[186] Like fascist regimes, Ba'athism became heavily militarized in power.[186] Ba'athist movements governed Iraq in 1963 and again from 1968 to 2003 and in Syria from 1963 to the present. Ba'athist heads of state such as Syrian President Hafez al-Assad and Iraqi President Saddam Hussein created personality cults around themselves portraying themselves as the nationalist saviours of the Arab world.[186]

Ba'athist Iraq under Saddam Hussein pursued ethnic cleansing or the liquidation of minorities, pursued expansionist wars against Iran and Kuwait and gradually replaced pan-Arabism with an Iraqi nationalism that emphasized Iraq's connection to the glories of ancient Mesopotamian empires, including Babylonia.[188] Historian on fascism Stanley Payne has said about Saddam Hussein's regime: "There will probably never again be a reproduction of the Third Reich, but Saddam Hussein has come closer than any other dictator since 1945".[188]

In the 1990s, Payne claimed that a prominent Hindu nationalist movement Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) holds strong resemblances to fascism—including its use of paramilitaries and its irredentist claims—calling for the creation of a Greater India.[189] Cyprian Blamires in World Fascism: A Historical Encyclopedia describes the ideology of the RSS as "fascism with Sanskrit characters" – a unique Indian variant of fascism.[190] Blamires notes that there is evidence that the RSS held direct contact with Italy's Fascist regime and admired European fascism.[190] a view with some support from A. James Gregor.[191] However, these views have met wide criticism,[191][192][193] especially from academics specializing Indian politics. Paul Brass, expert on Hindu-Muslim violence, notes that there are many problems with accepting this point of view and identified four reasons that it is difficult to define the Sangh as fascist. Firstly, most scholars of the field do not subscribe to the view the RSS is fascist, notably among them Christophe Jaffrelot,[192] A. James Gregor[191] and Chetan Bhatt.[194] The other reasons include an absence of charismatic leadership, a desire on the part of the RSS to differentiate itself from European fascism, major cultural differences between the RSS and European fascists and factionalism within the Sangh Parivar.[192] Stanley Payne claims that it also has substantial differences with fascism such as its emphasis on traditional religion as the basis of identity.[195]

Fascism's relationship with other political and economic ideologies

Mussolini saw fascism as opposing socialism and left-wing ideologies: "If it is admitted that the nineteenth century has been the century of Socialism, Liberalism and Democracy, it does not follow that the twentieth must also be the century of Liberalism, Socialism and Democracy. Political doctrines pass; peoples remain. It is to be expected that this century may be that of authority, a century of the "Right," a Fascist century".[196]

Capitalism

Fascism has had complicated relations regarding capitalism, which changed over time and differed between Fascist states. Fascists commonly have sought to eliminate the autonomy of large-scale capitalism to the state.[197] Fascists support the state having control over the economy, although they support the existence of private property.[198] When fascists have criticized capitalism, they have focused their attacks on "finance capitalism", the international nature of banks and the stock exchange and its cosmopolitan bourgeois character.[199] Under fascism, the profit motive continues to be the primary motivation of contributors to the economy.[198] That policy abruptly changed in Italy by 1934 when Mussolini "reiterated that capitalism, as an economic system, was no longer viable".[200] Mussolini went so far as to proclaim that the economy of Fascist Italy was to be "based not on individual profit but on collective interest".[201] Originally, Fascists theoreticians supported limited private property, individual initiative and market economy because it was—as expounded by Sergio Panunzio, a major theoretician of Italian Fascism-- "the only economic system that allowed a socialism for the entire nation" since it was believed to encourage "productionism".[202] Most Fascist theoreticians and revolutionary syndicalists followed Karl Marx's admonition that a nation required "full maturation of capitalism as the precondition for socialist realization".[203] Fascist intellectuals were determined to foster economic development in order for a syndicalist economy to "attain its productive maximum" that was identified as crucial to "socialist revolution".[204] Italian Fascism's position towards capitalism adjusted over time, as the Italian Fascist movement in 1919 was radical and anti-capitalist, where he continued to campaign for "nationalization of land" and to have "workers' participation in the running of factories",[205] but became more moderate in the 1920s when it sought to consolidate power, allied with the squadrismo and then grew more radical again during the 1930s under its entrenchment of power and by 1940 again emphasized anti-capitalism.

Mussolini praised the historic developments of "heroic capitalism" – what Mussolini considered the first stage of capitalism, which he found had provided useful economic developments, but he claimed that capitalism had deteriorated, and criticized the contemporary stage of capitalism that he termed "supercapitalism". He argued:

I do not intend to defend capitalism or capitalists. They, like everything human, have their defects. I only say their possibilities of usefulness are not ended. Capitalism has borne the monstrous burden of the war and today still has the strength to shoulder the burdens of peace. ... It is not simply and solely an accumulation of wealth, it is an elaboration, a selection, a co-ordination of values which is the work of centuries. ... Many think, and I myself am one of them, that capitalism is scarcely at the beginning of its story.[206]

Years later in a 14 November 1933 speech, Mussolini decidedly rebuked economic liberalism and laissez-faire. In the United States, the Hearst Press printed his speech under the headline: "Mussolini Abolishes the Capitalist System".[207] Mussolini declared:

To-day we can affirm that the capitalistic method of production is out of date. So is the doctrine of laissez-faire, the theoretical basis of capitalism… To-day we are taking a new and decisive step in the path of revolution. A revolution, in order to be great, must be a social revolution.[208]