Albert Speer

| Albert Speer | |

|---|---|

Speer in 1933 | |

| Minister of Armaments and War Production | |

|

In office February 8, 1942 – May 23, 1945 | |

| Head of state | |

| Head of government |

|

| Preceded by | Fritz Todt (as Minister of Armaments and Munitions) |

| Succeeded by | Karl Saur (as Minister of Munitions)[lower-alpha 1] |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Berthold Konrad Hermann Albert Speer March 19, 1905 Mannheim, Baden, German Empire |

| Died |

September 1, 1981 (aged 76) London, England, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | German |

| Political party | National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP) |

| Spouse(s) | Margarete Weber (1928–1981, his death) |

| Children | 6, including Albert, Hilde, Margarete |

| Alma mater | |

| Profession | Architect, government official, author |

| Signature |

|

Berthold Konrad Hermann Albert Speer[1] (/ʃpɛər/; German: [ˈʃpeːɐ̯] (![]()

Speer joined the Nazi Party in 1931, launching himself on a political and governmental career which lasted fourteen years. His architectural skills made him increasingly prominent within the Party and he became a member of Hitler's inner circle. Hitler instructed him to design and construct structures including the Reich Chancellery and the Zeppelinfeld stadium in Nuremberg where Party rallies were held. Speer also made plans to reconstruct Berlin on a grand scale, with huge buildings, wide boulevards, and a reorganized transportation system. In February 1942, Hitler appointed him as Reich Minister of Armaments and War Production.

After the war, he was tried at Nuremberg and sentenced to 20 years in prison for his role in the Nazi regime, principally for the use of forced labor. Despite repeated attempts to gain early release, he served his full sentence, most of it at Spandau Prison in West Berlin. Following his release in 1966, Speer published two bestselling autobiographical works, Inside the Third Reich and Spandau: The Secret Diaries, detailing his close personal relationship with Hitler, and providing readers and historians with a unique perspective on the workings of the Nazi regime. He wrote a third book, Infiltration, about the SS. Speer died of a stroke in 1981 while on a visit to London.

Early years

Speer was born in Mannheim, into an upper-middle-class family. He was the second of three sons of Luise Máthilde Wilhelmine (Hommel) and Albert Friedrich Speer.[2] In 1918, the family moved permanently to their summer home Villa Speer on Schloss-Wolfsbrunnenweg, Heidelberg.[3] According to Henry T. King, deputy prosecutor at Nuremberg who later wrote a book about Speer, "Love and warmth were lacking in the household of Speer's youth."[4] Speer was active in sports, taking up skiing and mountaineering. Speer's Heidelberg school offered rugby football, unusual for Germany, and Speer was a participant.[5] He wanted to become a mathematician, but his father said if Speer chose this occupation he would "lead a life without money, without a position and without a future".[6] Instead, Speer followed in the footsteps of his father and grandfather and studied architecture.[7]

Speer began his architectural studies at the University of Karlsruhe instead of a more highly acclaimed institution because the hyperinflation crisis of 1923 limited his parents' income.[8] In 1924 when the crisis had abated, he transferred to the "much more reputable" Technical University of Munich.[9] In 1925 he transferred again, this time to the Technical University of Berlin where he studied under Heinrich Tessenow, whom Speer greatly admired.[10] After passing his exams in 1927, Speer became Tessenow's assistant, a high honor for a man of 22.[11] As such, Speer taught some of Tessenow's classes while continuing his own postgraduate studies.[12] In Munich, and continuing in Berlin, Speer began a close friendship, ultimately spanning over 50 years, with Rudolf Wolters, who also studied under Tessenow.[13]

In mid-1922, Speer began courting Margarete (Margret) Weber (1905–1987), the daughter of a successful craftsman who employed 50 workers. The relationship was frowned upon by Speer's class-conscious mother, who felt that the Webers were socially inferior. Despite this opposition, the two married in Berlin on August 28, 1928; seven years elapsed before Margarete Speer was invited to stay at her in-laws' home.[14]

Nazi architect

Joining the Nazis (1930–1934)

Speer stated he was apolitical when he was a young man, and he attended a Berlin Nazi rally in December 1930 only at the urging of some of his students.[15] On March 1, 1931, he applied to join the Nazi Party and became member number 474,481.[16][17]

In 1931, Speer surrendered his position as Tessenow's assistant and moved to Mannheim. His father gave him a job as manager of the elder Speer's properties. In July 1932, the Speers visited Berlin to help out the Party prior to the Reichstag elections. While they were there, his friend, Nazi Party official Karl Hanke, recommended the young architect to Joseph Goebbels to help renovate the Party's Berlin headquarters. Speer agreed to do the work. When the commission was completed, Speer returned to Mannheim and remained there as Hitler took office in January 1933.[18][19]

The organizers of the 1933 Nuremberg Rally asked Speer to submit designs for the rally, bringing him into contact with Hitler for the first time. Neither the organizers nor Rudolf Hess were willing to decide whether to approve the plans, and Hess sent Speer to Hitler's Munich apartment to seek his approval.[20] This work won Speer his first national post, as Nazi Party "Commissioner for the Artistic and Technical Presentation of Party Rallies and Demonstrations".[21]

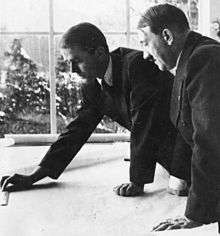

Shortly after Hitler had come into power, he had started to make plans to rebuild the chancellery. At the end of 1933 he contracted Paul Troost to renovate the entire building. Hitler appointed Speer, whose work for Goebbels had impressed him, to manage the building site for Troost.[22] As Chancellor, Hitler had a residence in the building and came by every day to be briefed by Speer and the building supervisor on the progress of the renovations. After one of these briefings, Hitler invited Speer to lunch, to the architect's great excitement.[23] Hitler evinced considerable interest in Speer during the luncheon, and later told Speer that he had been looking for a young architect capable of carrying out his architectural dreams for the new Germany. Speer quickly became part of Hitler's inner circle; he was expected to call on Hitler in the morning for a walk or chat, to provide consultation on architectural matters, and to discuss Hitler's ideas. Most days he was invited to dinner.[24][25]

The two men found much in common: Hitler spoke of Speer as a "kindred spirit" for whom he had always maintained "the warmest human feelings".[26] The young, ambitious architect was dazzled by his rapid rise and close proximity to Hitler, which guaranteed him a flood of commissions from the government and from the highest ranks of the Party.[27] Speer testified at Nuremberg, "I belonged to a circle which consisted of other artists and his personal staff. If Hitler had had any friends at all, I certainly would have been one of his close friends."[lower-alpha 3]

First Architect of Nazi Germany (1934–1939)

When Troost died on January 21, 1934, Speer effectively replaced him as the Party's chief architect. Hitler appointed Speer as head of the Chief Office for Construction, which placed him nominally on Hess's staff.[28]

One of Speer's first commissions after Troost's death was the Zeppelinfeld stadium—the Nürnberg parade grounds seen in Leni Riefenstahl's propaganda masterpiece Triumph of the Will. This huge work was able to hold 340,000 people.[29] Speer insisted that as many events as possible be held at night, both to give greater prominence to his lighting effects and to hide the individual Nazis, many of whom were overweight.[30] Speer surrounded the site with 130 anti-aircraft searchlights. Speer described this as his most beautiful work, and as the only one that stood the test of time.[31]

Nürnberg was to be the site of many more official Nazi buildings, most of which were never built; for example, the German Stadium would have accommodated 400,000 spectators, while an even larger rally ground would have held half a million people.[29] While planning these structures, Speer conceived the concept of "ruin value": that major buildings should be constructed in such a way they would leave aesthetically pleasing ruins for thousands of years into the future. Such ruins would be a testament to the greatness of Nazi Germany, just as ancient Greek or Roman ruins were symbols of the greatness of those civilizations.[32]

When Hitler deprecated Werner March's design for the Olympic Stadium for the 1936 Summer Olympics as too modern, Speer modified the plans by adding a stone exterior.[33] Speer designed the German Pavilion for the 1937 international exposition in Paris. The German and Soviet pavilion sites were opposite each other. On learning (through a clandestine look at the Soviet plans) that the Soviet design included two colossal figures seemingly about to overrun the German site, Speer modified his design to include a cubic mass which would check their advance, with a huge eagle on top looking down on the Soviet figures.[34] Speer received, from Hitler Youth leader and later fellow Spandau prisoner Baldur von Schirach, the Golden Hitler Youth Honor Badge with oak leaves.[35]

In 1937, Hitler appointed Speer as General Building Inspector for the Reich Capital with the rank of undersecretary of state in the Reich government. The position carried with it extraordinary powers over the Berlin city government and made Speer answerable to Hitler alone.[36] It also made Speer a member of the Reichstag, though the body by then had little effective power.[37] Hitler ordered Speer to develop plans to rebuild Berlin. The plans centered on a three-mile long grand boulevard running from north to south, which Speer called the Prachtstrasse, or Street of Magnificence;[38] he also referred to it as the "North-South Axis".[39] At the northern end of the boulevard, Speer planned to build the Volkshalle, a huge assembly hall with a dome which would have been over 700 feet (210 m) high, with floor space for 180,000 people. At the southern end of the avenue a great triumphal arch would rise; it would be almost 400 feet (120 m) high, and able to fit the Arc de Triomphe inside its opening. The outbreak of World War II in 1939 led to the postponement, and later the abandonment, of these plans.[40] Part of the land for the boulevard was to be obtained by consolidating Berlin's railway system.[41] Speer hired Wolters as part of his design team, with special responsibility for the Prachtstrasse.[42] When Speer's father saw the model for the new Berlin, he said to his son, "You've all gone completely insane."[43]

All the while plans to build a new Reich chancellery had been underway since 1934. Land had been purchased by the end of 1934 and starting in March 1936 the first buildings were demolished to create space at Voßstraße.[44] Speer was involved virtually from the beginning. He had been commissioned to renovate the Borsig Palace on the corner of Voßstraße and Wilhelmstraße as a headquarter for the SA, who were about to be relocated from Munich to Berlin in the aftermath of the Röhm purge.[45] and completed the preliminary work for the new chancellery by May 1936. In June 1936 he charged a personal honorarium of 30,000 Reichsmark and estimated that the chancellery would be completed within three to four years. Detailed plans were completed in July 1937 and the first shell of the new chancellery was complete on 1 January 1938. On 27 January 1938 Speer received plenipotentiary powers from Hitler to finish the new chancellery by 1 January 1939. Yet for propagandistic reasons, to prove the vigor and organizational skills of National Socialism, Hitler claimed during the topping-out ceremony on 2 August 1938 that he had ordered Speer to build the new chancellery just that year. Speer reiterated this claim in his memoirs to show that he had been up to that supposed challenge,[46] and some of his biographers, most notably Joachim Fest, have followed that account.[47] The building itself, hailed by Hitler as the "crowning glory of the greater German political empire", was designed as a theatrical set for representation, "to intimidate and humiliate", as historian Martin Kitchen puts it. Because of shortages of labor, the construction workers had to work in two ten- to twelve-hour shifts to have the chancellery completed by early January 1939.[48]

During the war the chancellery was destroyed, except for the exterior walls, by air raids and in the Battle of Berlin in 1945. It was eventually dismantled by the Soviets. Rumor has it that the remains have been used for other building projects like the Humboldt University, Mohrenstraße metro station or Soviet war memorials in Berlin, but none of these are true.[49]

During the Chancellery project, the pogrom of Kristallnacht took place. Speer made no mention of it in the first draft of Inside the Third Reich, and it was only on the urgent advice of his publisher that he added a mention of seeing the ruins of the Central Synagogue in Berlin from his car.[50]

Speer was under significant psychological pressure during this period of his life. He later remembered:

Soon after Hitler had given me the first large architectural commissions, I began to suffer from anxiety in long tunnels, in airplanes, or in small rooms. My heart would begin to race, I would become breathless, the diaphragm would seem to grow heavy, and I would get the impression that my blood pressure was rising tremendously ... Anxiety amidst all my freedom and power![lower-alpha 4]

Wartime architect (1939–1942)

Speer supported the German invasion of Poland and subsequent war, though he recognized that it would lead to the postponement, at the least, of his architectural dreams.[51] In his later years, Speer, talking with his biographer-to-be Gitta Sereny, explained how he felt in 1939: "Of course I was perfectly aware that [Hitler] sought world domination ...[A]t that time I asked for nothing better. That was the whole point of my buildings. They would have looked grotesque if Hitler had sat still in Germany. All I wanted was for this great man to dominate the globe."[52]

Speer placed his department at the disposal of the Wehrmacht. When Hitler remonstrated, and said it was not for Speer to decide how his workers should be used, Speer simply ignored him.[53] Among Speer's innovations were quick-reaction squads to construct roads or clear away debris; before long, these units would be used to clear bomb sites.[51] As the war progressed, initially to great German success, Speer continued preliminary work on the Berlin and Nürnberg plans.[54][55] Speer also oversaw the construction of buildings for the Wehrmacht and Luftwaffe.[56]

In 1940, Joseph Stalin proposed that Speer pay a visit to Moscow. Stalin had been particularly impressed by Speer's work in Paris, and wished to meet the "Architect of the Reich". Hitler, alternating between amusement and anger, did not allow Speer to go, fearing that Stalin would put Speer in a "rat hole" until a new Moscow arose.[57] When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, Speer came to doubt, despite Hitler's reassurances, that his projects for Berlin would ever be completed.[58]

Minister of Armaments

Appointment and increasing power

On February 8, 1942, Minister of Armaments Fritz Todt died in a plane crash shortly after taking off from Hitler's eastern headquarters at Rastenburg. Speer, who had arrived in Rastenburg the previous evening, had accepted Todt's offer to fly with him to Berlin, but had cancelled some hours before takeoff (Speer stated in his memoirs that the cancellation was because of exhaustion from travel and a late-night meeting with Hitler). Later that day, Hitler appointed Speer as Todt's successor to all of his posts. In Inside the Third Reich, Speer recounts his meeting with Hitler and his reluctance to take ministerial office, saying that he only did so because Hitler commanded it. Speer also states that Hermann Göring raced to Hitler's headquarters on hearing of Todt's death, hoping to claim Todt's powers. Hitler instead presented Göring with the fait accompli of Speer's appointment.[59]

At the time of Speer's accession to the office, the German economy, unlike the British one, was not fully geared for war production. Consumer goods were still being produced at nearly as high a level as during peacetime. No fewer than five "Supreme Authorities" had jurisdiction over armament production—one of which, the Ministry of Economic Affairs, had declared in November 1941 that conditions did not permit an increase in armament production. Few women were employed in the factories, which were running only one shift. One evening soon after his appointment, Speer went to visit a Berlin armament factory; he found no one on the premises.[60]

Speer overcame these difficulties by centralizing power over the war economy in himself. Factories were given autonomy, or as Speer put it, "self-responsibility", and each factory concentrated on a single product.[61] Backed by Hitler's strong support (the dictator stated, "Speer, I'll sign anything that comes from you"[62]), he divided the armament field according to weapon system, with experts rather than civil servants overseeing each department. No department head could be older than 55—anyone older being susceptible to "routine and arrogance"[63]—and no deputy older than 40. Over these departments was a central planning committee headed by Speer, which took increasing responsibility for war production, and as time went by, for the German economy itself. According to the minutes of a conference at Wehrmacht High Command in March 1942, "It is only Speer's word that counts nowadays. He can interfere in all departments. Already he overrides all departments ... On the whole, Speer's attitude is to the point."[64] Goebbels would note in his diary in June 1943, "Speer is still tops with the Führer. He is truly a genius with organization."[65] Speer was so successful in his position that by late 1943, he was widely regarded among the Nazi elite as a possible successor to Hitler.[66]

While Speer had tremendous power, he was of course subordinate to Hitler. Nazi officials sometimes went around Speer by seeking direct orders from the dictator. When Speer ordered peacetime building work suspended, the Gauleiters (Nazi Party district leaders) obtained an exemption for their pet projects. When Speer sought the appointment of Hanke as a labor czar to optimize the use of German and slave labor, Hitler, under the influence of Martin Bormann, instead appointed Fritz Sauckel. Rather than increasing female labor and taking other steps to better organize German labor, as Speer favored, Sauckel advocated importing more slave labour from the occupied nations – and did so, obtaining workers for (among other things) Speer's armament factories, often using the most brutal methods.[67]

On December 10, 1943, Speer visited the underground Mittelwerk V-2 rocket factory that used concentration camp labor. Speer claimed after the war that he had been shocked by the conditions there (5.7 percent of the work force died that month).[68][69]

By 1943, the Allies had gained air superiority over Germany, and bombings of German cities and industry had become commonplace. However, the Allies in their strategic bombing campaign did not concentrate on industry, and Speer was able to overcome bombing losses. In spite of these losses, German production of tanks more than doubled in 1943, production of planes increased by 80 percent, and production time for Kriegsmarine's submarines was reduced from one year to two months. Production would continue to increase until the second half of 1944.[70]

Consolidation of arms production

In January 1944, Speer fell ill with complications from an inflamed knee, necessitating a leave. According to Speer's post-war memoirs, his political rivals (mainly Göring and Martin Bormann), attempted to have some of his powers permanently transferred to them during his absence. Speer claimed that SS chief Heinrich Himmler tried to have him physically isolated by having Himmler's personal physician Karl Gebhardt treat him, though his "care" did not improve his health. Speer's case was transferred to his friend Dr. Karl Brandt, and he slowly recovered.[71]

In response to the Allied air raids on aircraft factories, Adolf Hitler authorised the creation of a Jägerstab, a governmental task force composed of Reich Aviation Ministry, Armaments Ministry and SS personnel. Its aim was to ensure the preservation and growth of fighter aircraft production. The task force was established by the 1 March 1944 order of Speer, with support from Erhard Milch of the Reich Aviation Ministry. Speer and Milch played a key role in directing the activities of the agency, while the day-to-day operations were handled by Chief of Staff Karl Saur, the head of the Technical Office in the Armaments Ministry.[72] Production continued to improve until late 1944, with allied bombing destroying just 9% of German production. Production of German fighter aircraft was more than doubled from 1943 to 1944.[73]

In April, Speer's rivals for power succeeded in having him deprived of responsibility for construction. Speer sent Hitler a bitter letter, concluding with an offer of his resignation. Judging Speer indispensable to the war effort, Field Marshal Erhard Milch persuaded Hitler to try to get his minister to reconsider. Hitler sent Milch to Speer with a message not addressing the dispute but instead stating that he still regarded Speer as highly as ever. According to Milch, upon hearing the message, Speer burst out, "The Führer can kiss my ass!"[74] After a lengthy argument, Milch persuaded Speer to withdraw his offer of resignation, on the condition his powers were restored.[75] On April 23, 1944, Speer went to see Hitler who agreed that "everything [will] stay as it was, [Speer will] remain the head of all German construction".[76] According to Speer, while he was successful in this debate, Hitler had also won, "because he wanted and needed me back in his corner, and he got me".[77]

The Jägerstab was given extraordinary powers over labour, production and transportation resources, with its functions taking priority over housing repairs for bombed out civilians or restoration of vital city services. The factories that came under the Jägerstab program saw their work-weeks extended to 72 hours. At the same time, Milch took steps to rationalise production by reducing the number of variants of each type of aircraft produced.[78]

The Jägerstab was instrumental in bringing about the increased exploitation of slave labour for the benefit of Germany's war industry and its air force, the Luftwaffe. The task force immediately began implementing plans to expand the use of slave labour in the aviation manufacturing.[79] Records show that SS provided 64,000 prisoners for 20 separate projects at the peak of Jägerstab's construction activities. Taking into account the high mortality rate associated with the underground construction projects, the historian Marc Buggeln estimates that the workforce involved amounted to 80,000−90,000 inmates. They belonged to the various sub-camps of Mittelbau-Dora, Mauthausen-Gusen, Buchenwald and other camps. The prisoners worked for Junkers, Messerschmitt, Henschel and BMW, among others.[80]

The cooperation between the Reich Ministry of Aviation, the Ministry of Armaments and the SS proved especially productive. Although intended to function for only six months, already in late May Speer and Milch discussed with Goring the possibility of centralising all of Germany's arms manufacturing under a similar task force. On 1 August 1944, Speer reorganised the Jägerstab into the Rüstungsstab (Armament Staff) to apply the same model of operation to all top-priority armament programs.[81]

The formation of the Rüstungsstab allowed Speer, for the first time, to consolidate key arms manufacturing projects for the three branches of the Wehrmacht under the authority of his ministry, further marginalising the Reich Ministry of Aviation. Several departments, including the once powerful Technical Office, were disbanded or transferred to the new task force.[82] The task force oversaw the day-to-day development and production activities relating to the He 162, the Volksjäger ("people's fighter"), as part of the Emergency Fighter Program.[83]

The Rüstungsstab assumed responsibilities for the underground transfer projects of the Jägerstab. In November 1944, 1.8 million square meters of underground space were ready for occupancy, encompassing over 1,000 spaces commissioned by the task force. But by this time German production was beginning to collapse.[73] (Post-war, Speer sought to downplay his involvement with these projects and claimed that only 300,000 square meters had been completed). According to Buggeln, the Rüstungsstab played a key role in maintaining and increasing production of fighter aircraft and V-2 rockets.[84]

Defeat of Nazi Germany

Speer's name was included on the list of members of a post-Hitler government drawn up by the conspirators behind the July 1944 assassination plot to kill Hitler. The list had a question mark and the annotation "to be won over" by his name, which likely saved him from the extensive purges that followed the scheme's failure.[85]

When Speer learned in February 1945 that the Red Army had overrun the Silesian industrial region, he drafted a memo to Hitler noting that Silesia's coal mines now supplied 60 percent of the Reich's coal. Without them, Speer wrote, Germany's coal production would only be a quarter of its 1944 total—not nearly enough to continue the war. He told Hitler in no uncertain terms that without Silesia, "the war is lost." Hitler merely filed the memo in his safe.[86]

By February 1945, Speer was working to supply areas about to be occupied with food and materials to get them through the hard times ahead.[87] On March 19, 1945, Hitler issued his Nero Decree, ordering a scorched earth policy in both Germany and the occupied territories.[88] The plan included forcing millions of people on a long trek without food or supplies which would have resulted in a "hunger catastrophe" according to Speer; Hitler had no compunction about this, believing that only the "inferior ones" would have survived the battles.[89]

Hitler's order, by its terms, deprived Speer of any power to interfere with the decree, and Speer went to confront Hitler, reiterating that the war was lost.[90] Hitler gave Speer 24 hours to reconsider his position, and when the two met the following day, Speer answered, "I stand unconditionally behind you."[91] However, he demanded the exclusive power to implement the Nero Decree, and Hitler signed an order to that effect. Using this order, Speer worked to persuade generals and Gauleiters to circumvent the Nero Decree and avoid needless sacrifice of personnel and destruction of industry that would be needed after the war.[92] Shirer describes this as a "superhuman effort" by Speer and a number of army officials, acting contrary to Hitler's orders, to save vital communications, plants and stores.[93]

Speer managed to reach a relatively safe area near Hamburg as the Nazi regime finally collapsed, but decided on a final, risky visit to Berlin to see Hitler one more time.[94] Speer stated at Nuremberg, "I felt that it was my duty not to run away like a coward, but to stand up to him again."[95] Speer visited the Führerbunker on April 22. Hitler seemed calm and somewhat distracted, and the two had a long, disjointed conversation in which the dictator defended his actions and informed Speer of his intent to commit suicide and have his body burned. In the published edition of Inside the Third Reich, Speer relates that he confessed to Hitler that he had defied the Nero Decree, but then assured Hitler of his personal loyalty, bringing tears to the dictator's eyes.[94] Speer biographer Gitta Sereny argued, "Psychologically, it is possible that this is the way he remembered the occasion, because it was how he would have liked to behave, and the way he would have liked Hitler to react. But the fact is that none of it happened; our witness to this is Speer himself."[96] Sereny notes that Speer's original draft of his memoirs lacks the confession and Hitler's tearful reaction, and contains an explicit denial that any confession or emotional exchange took place, as had been alleged in a French magazine article.[97]

The following morning, Speer left the Führerbunker; Hitler curtly bade him farewell. Speer toured the damaged Chancellery one last time before leaving Berlin to return to Hamburg.[94] On April 29, the day before committing suicide, Hitler dictated a final political testament which dropped Speer from the successor government. Speer was to be replaced by his own subordinate, Karl-Otto Saur.[98]

Post-war

Nuremberg trial

After Hitler's death, Speer offered his services to the so-called Flensburg Government, headed by Hitler's successor, Karl Dönitz, and took a significant role in that short-lived regime as Minister of Industry and Production.[99] On May 15, an Allied delegation arrived at Glücksburg Castle, where Speer had accommodations, and asked if he would be willing to provide information on the effects of the air war.[100] Speer agreed, and over the next several days, provided information on a broad range of subjects. On May 23, two weeks after the surrender of German forces, British troops arrested the members of the Flensburg Government and brought Nazi Germany to a formal end.[99]

Speer was taken to several internment centres for Nazi officials and interrogated. In September 1945, he was told that he would be tried for war crimes, and several days later, he was taken to Nuremberg and incarcerated there.[101] Speer was indicted on all four possible counts: first, participating in a common plan or conspiracy for the accomplishment of crime against peace; second, planning, initiating and waging wars of aggression and other crimes against peace; third, war crimes; and lastly, crimes against humanity.[102]

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson, the chief U.S. prosecutor at Nuremberg, alleged, "Speer joined in planning and executing the program to dragoon prisoners of war and foreign workers into German war industries, which waxed in output while the workers waned in starvation."[103] Speer's attorney, Dr. Hans Flächsner, presented Speer as an artist thrust into political life, who had always remained a non-ideologue and who had been promised by Hitler that he could return to architecture after the war.[104] During his testimony, Speer accepted responsibility for the Nazi regime's actions.[105]

An observer at the trial, journalist and author William L. Shirer, wrote that, compared to his codefendants, Speer "made the most straightforward impression of all and ... during the long trial spoke honestly and with no attempt to shirk his responsibility and his guilt".[106] Speer claimed that he had planned to kill Hitler in early 1945 by introducing tabun poison gas into the Führerbunker ventilation shaft.[107][108] He said his efforts were frustrated by the impracticability of tabun and his lack of ready access to a replacement nerve agent,[108] and also by the unexpected construction of a tall chimney that put the air intake out of reach.[109] Speer stated his motive was despair at realising that Hitler intended to take the German people down with him.[107] Speer's supposed assassination plan subsequently met with some skepticism, with Speer's architectural rival Hermann Giesler sneering, "the second most powerful man in the state did not have a ladder."[110]

Speer was found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity, though he was acquitted on the other two counts. His claim that he was unaware of Nazi extermination plans, which probably saved him from hanging, was finally revealed to be false in a private correspondence written in 1971 and publicly disclosed in 2007.[111] On 1 October 1946, he was sentenced to 20 years' imprisonment.[112] While three of the eight judges (two Soviet and one American) initially advocated the death penalty for Speer, the other judges did not, and a compromise sentence was reached "after two days' discussion and some rather bitter horse-trading".[113]

The court's judgment stated that:

... in the closing stages of the war [Speer] was one of the few men who had the courage to tell Hitler that the war was lost and to take steps to prevent the senseless destruction of production facilities, both in occupied territories and in Germany. He carried out his opposition to Hitler's scorched earth programme ... by deliberately sabotaging it at considerable personal risk.[114]

Imprisonment

- For additional detail on Speer's time at Spandau Prison, see Rudolf Wolters#Spandau years

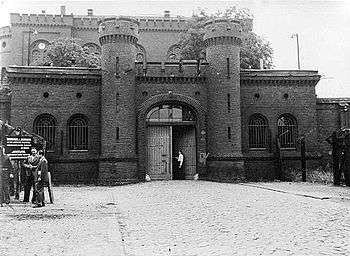

On July 18, 1947, Speer and his six fellow prisoners, all former high officials of the Nazi regime, were flown from Nuremberg to Berlin under heavy guard.[115] They were taken to Spandau Prison in the British Sector of what became West Berlin where they were designated by number, with Speer given Number Five.[116] Initially, the prisoners were kept in solitary confinement for all but half an hour a day and were not permitted to address each other or their guards.[117] As time passed, the strict regimen was relaxed, especially during the three months out of four that the three Western powers were in control; the four occupying powers took overall control on a monthly rotation.[118]

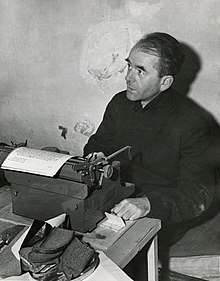

Speer considered himself an outcast among his fellow prisoners for his acceptance of responsibility at Nuremberg.[119] He made a deliberate effort to use his time as productively as possible. He wrote, "I am obsessed with the idea of using this time of confinement for writing a book of major importance ... That could mean transforming prison cell into scholar's den."[120] The prisoners were forbidden to write memoirs, and mail was severely limited and censored. However, Speer was able to have his writings sent to Wolters as a result of an offer from a sympathetic orderly, and they eventually amounted to 20,000 sheets. He had completed his memoirs by 1954, which became the basis of Inside the Third Reich and which Wolters arranged to have transcribed onto 1,100 typewritten pages.[121] He was also able to send letters and financial instructions and to obtain writing paper and letters from the outside.[122] His many letters to his children were secretly transmitted and eventually formed the basis for Spandau: The Secret Diaries.[123]

With the draft memoir complete and clandestinely transmitted, Speer sought a new project. He found one while taking his daily exercise, walking in circles around the prison yard. Measuring the path's distance carefully, he set out to walk the distance from Berlin to Heidelberg. He then expanded his idea into a worldwide journey, visualizing the places that he was "traveling" through while walking the path around the prison yard. He ordered guidebooks and other materials about the nations through which he imagined that he was passing so as to envision as accurate a picture as possible.[124] He meticulously calculated every meter traveled and mapped distances to the real-world geography. He began in northern Germany, passed through Asia by a southern route before entering Siberia, then crossed the Bering Strait and continued southwards, finally ending his sentence 35 kilometres (22 mi) south of Guadalajara, Mexico.[125]

Speer devoted much of his time and energy to reading. The prisoners brought some books with them in their personal property, but Spandau Prison had no library; books were sent from Spandau's municipal library.[126] From 1952, the prisoners were also able to order books from the Berlin central library in Wilmersdorf.[127] Speer was a voracious reader and he completed well over 500 books in the first three years at Spandau alone.[128] He read classic novels, travelogues, books on ancient Egypt, and biographies of such figures as Lucas Cranach, Édouard Manet, and Genghis Khan.[127] He took to the prison garden for enjoyment and work, at first to do something constructive while afflicted with writer's block.[129] He was allowed to build an ambitious garden, transforming what he initially described as a "wilderness"[130] into what the American commander at Spandau described as "Speer's Garden of Eden".[131]

Speer's supporters maintained a continual call for his release. Among those who pledged support for his sentence to be commuted were Charles de Gaulle,[132] U.S. diplomat George Ball,[132] former U.S. High Commissioner John J. McCloy,[133] and former Nuremberg prosecutor Hartley Shawcross.[133] Willy Brandt was a strong advocate of his release,[134] sending flowers to his daughter on the day of his release[135] and putting an end to the de-Nazification proceedings against him,[136] which could have caused his property to be confiscated.[137] A reduced sentence required the consent of all four of the occupying powers, and the Soviets adamantly opposed any such proposal.[133] Speer served his full sentence and was released at midnight on October 1, 1966.[138]

Release and later life

Speer's release from prison was a worldwide media event, as reporters and photographers crowded both the street outside Spandau and the lobby of the Berlin hotel where Speer spent his first hours of freedom in over 20 years.[139] He said little, reserving most comments for a major interview published in Der Spiegel in November 1966 in which he again took personal responsibility for crimes of the Nazi regime.[140] He abandoned plans to return to architecture, as two proposed partners died shortly before his release.[141] Instead, he revised his Spandau writings into two autobiographical books, and later researched and published a work about Himmler and the SS. His books provide a unique and personal look into the personalities of the Nazi era, most notably Inside the Third Reich (in German, Erinnerungen, or Reminiscences[142]) and Spandau: The Secret Diaries, and they have become much valued by historians. Speer was aided in shaping the works by Joachim Fest and Wolf Jobst Siedler from the publishing house Ullstein.[143] He found himself unable to re-establish his relationship with his children, even with his son Albert who had also become an architect. According to Speer's daughter Hilde, "One by one my sister and brothers gave up. There was no communication."[144]

Following the publication of his bestselling books, Speer donated a considerable amount of money to Jewish charities. According to Siedler, these donations were as high as 80 percent of his royalties. Speer kept the donations anonymous, both for fear of rejection and for fear of being called a hypocrite.[145]

Wolters strongly objected to Speer referring to Hitler in the memoirs as a criminal, and Speer predicted as early as 1953 that he would lose a "good many friends" if the writings were published.[121] This came to pass following the publication of Inside the Third Reich, as close friends distanced themselves from him, such as Wolters and sculptor Arno Breker. Hitler's personal pilot Hans Baur suggested that "Speer must have taken leave of his senses."[146] Wolters wondered that Speer did not now "walk through life in a hair shirt, distributing his fortune among the victims of National Socialism, forswear all the vanities and pleasures of life and live on locusts and wild honey".[147]

Speer made himself widely available to historians and other enquirers.[148] He did an extensive, in-depth interview for the June 1971 issue of Playboy magazine, in which he stated, "If I didn't see it, then it was because I didn't want to see it."[149] In October 1973, Speer made his first trip to Britain, flying to London under an assumed name[148] to be interviewed by Ludovic Kennedy on the BBC Midweek programme.[150] Upon arrival, he was detained for almost eight hours at Heathrow Airport when British immigration authorities discovered his true identity. Home Secretary Robert Carr allowed him into the country for 48 hours.[151] In the same year, he appeared on the television programme The World at War.

Speer returned to London in 1981 to participate in the BBC Newsnight program; while there, he suffered a stroke and died on September 1.[152] He had formed a relationship with an Englishwoman of German origin and was with her at the time of his death.[153] Even to the end of his life, Speer continued to question his actions under Hitler. He asks in his final book Infiltration, "What would have happened if Hitler had asked me to make decisions that required the utmost hardness? ... How far would I have gone? ... If I had occupied a different position, to what extent would I have ordered atrocities if Hitler had told me to do so?"[154] Speer leaves the questions unanswered.[154]

Legacy and controversy

The view of Speer as an unpolitical "miracle man" is challenged by Columbia historian Adam Tooze.[155] In his 2006 book, The Wages of Destruction, Tooze, following Gitta Sereny, argues that Speer's ideological commitment to the Nazi cause was greater than he claimed.[156] Tooze further contends that an insufficiently challenged Speer "mythology"[lower-alpha 5] (partly fostered by Speer himself through politically motivated, tendentious use of statistics and other propaganda)[157] had led many historians to assign Speer far more credit for the increases in armaments production than was warranted and give insufficient consideration to the "highly political" function of the so-called armaments miracle.[lower-alpha 6]

Architectural legacy

Little remains of Speer's personal architectural works, other than the plans and photographs. No buildings designed by Speer during the Nazi era are extant in Berlin, other than the Schwerbelastungskörper (heavy load bearing body), built around 1941. The 46-foot (14 m) high concrete cylinder was used to measure ground subsidence as part of feasibility studies for a massive triumphal arch and other large structures proposed as part of Welthauptstadt Germania, Hitler's planned postwar renewal project for the city. The cylinder is now a protected landmark and is open to the public. Along the Strasse des 17. Juni, a double row of lampposts designed by Speer still stands.[158] The tribune of the Zeppelinfeld stadium in Nuremberg, though partly demolished, can also be seen.[159]

More of Speer's own personal work can be found in London, where he redesigned the interior of the German Embassy to the United Kingdom, then located at 7–9 Carlton House Terrace. Since 1967, it has served as the offices of the Royal Society. His work there, stripped of its Nazi fixtures and partially covered by carpets, survives in part.[160]

Another legacy was the Arbeitsstab Wiederaufbau zerstörter Städte (Working group on Reconstruction of destroyed cities), authorised by Speer in 1943 to rebuild bombed German cities to make them more livable in the age of the automobile.[161] Headed by Wolters, the working group took a possible military defeat into their calculations.[161] The Arbeitsstab's recommendations served as the basis of the postwar redevelopment plans in many cities, and Arbeitsstab members became prominent in the rebuilding.[161]

Actions regarding the Jews

As General Building Inspector, Speer was responsible for the Central Department for Resettlement.[162] From 1939 onward, the Department used the Nuremberg Laws to evict Jewish tenants of non-Jewish landlords in Berlin, to make way for non-Jewish tenants displaced by redevelopment or bombing.[162] Eventually, 75,000 Jews were displaced by these measures.[163] Speer was aware of these activities, and inquired as to their progress.[164] At least one original memo from Speer so inquiring still exists,[164] as does the Chronicle of the Department's activities, kept by Wolters.[165]

Following his release from Spandau, Speer presented to the German Federal Archives an edited version of the Chronicle, stripped by Wolters of any mention of the Jews.[166] When David Irving discovered discrepancies between the edited Chronicle and other documents, Wolters explained the situation to Speer, who responded by suggesting to Wolters that the relevant pages of the original Chronicle should "cease to exist".[167] Wolters did not destroy the Chronicle, and, as his friendship with Speer deteriorated, allowed access to the original Chronicle to doctoral student Matthias Schmidt (who, after obtaining his doctorate, developed his thesis into a book, Albert Speer: The End of a Myth).[168] Speer considered Wolters' actions to be a "betrayal" and a "stab in the back".[169] The original Chronicle reached the Archives in 1983, after both Speer and Wolters had died.[165]

Knowledge of the Holocaust

Speer maintained at Nuremberg and in his memoirs that he had no knowledge of the Holocaust. He later wrote that in mid-1944, he was told by Hanke (by then Gauleiter of Lower Silesia) that the minister should never accept an invitation to inspect a concentration camp in neighbouring Upper Silesia, as "he had seen something there which he was not permitted to describe and moreover could not describe".[170] Speer later concluded that Hanke must have been speaking of Auschwitz and blamed himself for not inquiring further of Hanke or seeking information from Himmler or Hitler:

These seconds [when Hanke told Speer this, and Speer did not inquire] were uppermost in my mind when I stated to the international court at the Nuremberg Trial that, as an important member of the leadership of the Reich, I had to share the total responsibility for all that had happened. For from that moment on I was inescapably contaminated morally; from fear of discovering something which might have made me turn from my course, I had closed my eyes ... Because I failed at that time, I still feel, to this day, responsible for Auschwitz in a wholly personal sense.[171]

Historian Martin Kitchen indicates that Speer and his team were in charge of building concentration camps and were thus intimately involved in the "Final Solution".[172] He refers to a letter dated 1 February 1943 from Speer to Himmler about concentration camps containing 40,000 Jews or White Russians, suggesting that Speer had greater knowledge of the "Final Solution" than he admitted. When questioned, Speer denied any knowledge of this correspondence although it had gone out under his signature. Speer later insisted that he had tried to save some Jews from camps by using them in the armaments industry. These were "undernourished, overworked slaves", according to Kitchen, who adds that the death rate was "exceedingly high" among such workers.[173]

Much of the controversy over Speer's knowledge of the Holocaust has centered on his presence at the Posen Conference on October 6, 1943, at which Himmler gave a speech detailing the ongoing Holocaust to Nazi leaders. Himmler said, "The grave decision had to be taken to cause this people to vanish from the earth ... In the lands we occupy, the Jewish question will be dealt with by the end of the year."[174] Speer is mentioned several times in the speech, and Himmler seems to address him directly.[175] In Inside the Third Reich, Speer mentions his own address to the officials (which took place earlier in the day) but does not mention Himmler's speech.[176][177]

In October 1971, American historian Erich Goldhagen published an article arguing that Speer was present for Himmler's speech.[178] According to Fest in his biography of Speer, "Goldhagen's accusation certainly would have been more convincing"[179] had he not placed supposed incriminating statements linking Speer with the Holocaust in quotation marks, attributed to Himmler, which were in fact invented by Goldhagen.[179] In response, after considerable research in the German Federal Archives in Koblenz, Speer said he had left Posen around noon (long before Himmler's speech) to journey to Hitler's headquarters at Rastenburg.[179] In Inside the Third Reich, published before the Goldhagen article, Speer recalled that on the evening after the conference, many Nazi officials were so drunk that they needed help boarding the special train which was to take them to a meeting with Hitler.[180] One of his biographers, Dan van der Vat, suggests this necessarily implies he must have still been present at Posen then and must have heard Himmler's speech.[181] In response to Goldhagen's article, Speer had alleged that in writing Inside the Third Reich, he erred in reporting an incident that happened at another conference at Posen a year later, as happening in 1943.[182] In 2007, The Guardian reported that a letter from Speer dated December 23, 1971, had been found in Britain in a collection of his correspondence to Hélène Jeanty, widow of a Belgian resistance fighter. In the letter, Speer states that he had been present for Himmler's presentation in Posen. Speer wrote: "There is no doubt – I was present as Himmler announced on October 6, 1943, that all Jews would be killed."[111]

In 2005, The Daily Telegraph reported that documents had surfaced indicating that Speer had approved the allocation of materials for the expansion of Auschwitz after two of his assistants toured the facility on a day when almost a thousand Jews were killed. The documents bore annotations in Speer's own handwriting. Speer biographer Gitta Sereny stated that, due to his workload, Speer would not have been personally aware of such activities.[183]

The debate over Speer's knowledge of, or complicity in, the Holocaust made him a symbol for people who were involved with the Nazi regime yet did not have (or claimed not to have had) an active part in the regime's atrocities. As film director Heinrich Breloer remarked, "[Speer created] a market for people who said, 'Believe me, I didn't know anything about [the Holocaust]. Just look at the Führer's friend, he didn't know about it either.'"[183]

See also

References

Explanatory notes

- ↑ Although dismissed by Hitler, Speer was immediately re-appointed in the Flensburg Government as Minister of Economics.

- ↑ The title of a BBC2 documentary, The Nazi Who Said Sorry.

- ↑ Fest 1999, p. 296. "Wenn Hitler überhaupt Freunde gehabt hätte, wäre ich bestimmt einer seiner engen Freunde gewesen."

- ↑ Speer 1975, p. 217. Diary entry made on Nov, 20, 1949.

- ↑ Tooze 2006, p. 577. "The simple story spun by Speer, that the German war economy up to 1941 was an inefficient sink for labour and raw materials and that it was only after December 1941, by means of the Fuehrer's decree and Speer's inspired leadership, that it was awakened to the need for efficiency, is clearly a myth [and] the statistics usually invoked to support this description of the pre-Speer era simply do not stand up to detailed scrutiny."

- ↑ Tooze 2006, p. 556. "[G]iven the highly political function of the 'armaments miracle' the historical record of the Speer Ministry must be approached with a very wary eye. Too many historians have been far too uncritical in the acceptance of Speer's rhetoric of rationalization, efficiency and productivism. . . . And this critique is more than mere nit-picking. It goes to the very heart of Speer's ideological vision of the war economy, as a limitless flow of output released by energetic leadership and technological genius."

Citations

- ↑ van der Vat 1997, p. 11.

- ↑ Schubert 2006, p. 5.

- ↑ Speer 1970, p. 7.

- ↑ King 1997, p. 27.

- ↑ van der Vat 1997, p. 23.

- ↑ Schmidt 1984, p. 28.

- ↑ Fest 1999, pp. 11–13.

- ↑ Speer 1970, p. 9.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, p. 63.

- ↑ Speer 1970, pp. 10–11.

- ↑ van der Vat 1997, pp. 34–36.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, pp. 71–73.

- ↑ van der Vat 1997, pp. 33–34.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, pp. 47–49.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, p. 79.

- ↑ Speer 1970, pp. 15–17.

- ↑ Fest 1999, p. 29.

- ↑ Fest 1999, pp. 28–30.

- ↑ Speer 1970, pp. 22–25.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, pp. 100–01.

- ↑ van der Vat 1997, p. 49.

- ↑ Kitchen 2015, p. 41.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, pp. 101–03.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, p. 106.

- ↑ Kitchen 2015, pp. 41–42.

- ↑ Fest 1999, p. 42.

- ↑ Fest 1999, p. 54.

- ↑ van der Vat 1997, p. 60.

- 1 2 van der Vat 1997, p. 59.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, p. 131.

- ↑ Speer 1970, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ Speer 1970, pp. 55–56.

- ↑ van der Vat 1997, p. 65.

- ↑ Paris World Exposition 1937.

- ↑ Angolia 1978, p. 194.

- ↑ Fest 1999, p. 64.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, p. 144.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, p. 140.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, p. 141.

- ↑ Fest 1999, p. 71.

- ↑ Speer 1970, p. 77.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, p. 27.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, p. 158.

- ↑ Kitchen 2015, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Kitchen 2015, p. 45.

- ↑ Kitchen 2015, pp. 46–49.

- ↑ Fest 1999, pp. 101–06.

- ↑ Kitchen 2015, pp. 53–56.

- ↑ Kitchen 2015, p. 56.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, p. 164.

- 1 2 Fest 1999, p. 115.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, p. 186.

- ↑ Fest 1999, pp. 111–12.

- ↑ Speer 1970, pp. 176–78.

- ↑ Speer 1970, pp. 180–81.

- ↑ Speer 1970, p. 182.

- ↑ Fest 2007, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Fest 2007, p. 69.

- ↑ Speer 1970, pp. 193–96.

- ↑ Fest 1999, pp. 139–41.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, p. 295.

- ↑ Fest 1999, p. 143.

- ↑ Fest 2007, p. 76.

- ↑ Fest 1999, pp. 142–44.

- ↑ Schmidt 1984, p. 75.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, pp. 376–77.

- ↑ Fest 1999, pp. 146–50.

- ↑ van der Vat 1997, pp. 175–76.

- ↑ Speer 1970, p. 370.

- ↑ Fest 1999, pp. 168–70.

- ↑ Speer 1970, pp. 330–13.

- ↑ Boog et al 2006, p. 347.

- 1 2 Overy 2002, p. 343.

- ↑ Fest 1999, p. 210.

- ↑ Fest 1999, pp. 207–12.

- ↑ Speer 1981, pp. 232–33.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, p. 429.

- ↑ Boog et al 2006, p. 348.

- ↑ Buggeln 2014, p. 45.

- ↑ Buggeln 2014, p. 46–48.

- ↑ Uziel 2012, p. 82.

- ↑ Uziel 2012, p. 83.

- ↑ Uziel 2012, pp. 83, 240.

- ↑ Buggeln 2014, p. 43.

- ↑ Fest 1999, pp. 224–26.

- ↑ Shirer 1960, pp. 1096–97.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, p. 482.

- ↑ Fest 1999, pp. 250–51.

- ↑ Shirer 1960, p. 1104.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, pp. 486–92.

- ↑ Speer 1976, pp. 4–6.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, pp. 498–504.

- ↑ Shirer 1960, pp. 1104–1105.

- 1 2 3 Fest 1999, pp. 263–70.

- ↑ Speer cross-examination.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, p. 529.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, pp. 528–31.

- ↑ van der Vat 1997, p. 234.

- 1 2 Fest 1999, pp. 273–81.

- ↑ Speer 1970, p. 628.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, p. 561.

- ↑ Fest 1999, p. 285.

- ↑ Conot 1983, p. 471.

- ↑ Fest 1999, pp. 287–88.

- ↑ Speer 1970, p. 516.

- ↑ Shirer 1960, p. 1142–43.

- 1 2 Fest 1999, pp. 293–97.

- 1 2 Speer 1970, pp. 430–31.

- ↑ Fest 1999, pp. 245–46.

- ↑ Fest 1999, p. 246.

- 1 2 Connolly 2007.

- ↑ van der Vat 1997, pp. 281–82.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, p. 29.

- ↑ Fest 1999, p. 306.

- ↑ Speer 1976, pp. 65–67.

- ↑ Speer 1976, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Fest 1999, pp. 309–10.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, p. 602.

- ↑ Speer 1976, p. 244.

- ↑ Speer 1976, p. 75.

- 1 2 Fest 1999, p. 316.

- ↑ Fest 1999, pp. 310–11.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, p. 672.

- ↑ Fest 1999, pp. 316–17.

- ↑ Speer 1976, p. 447.

- ↑ Speer 1976, p. 69.

- 1 2 Speer 1976, p. 195.

- ↑ Fishman 1986, p. 129.

- ↑ Fest 1999, p. 312.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, p. 605.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, p. 654.

- 1 2 Fest 1999, p. 319.

- 1 2 3 Speer 1976, p. 440.

- ↑ van der Vat 1997, p. 319.

- ↑ Speer 1976, p. 448.

- ↑ van der Vat 1997, p. 324.

- ↑ van der Vat 1997, pp. 299–300.

- ↑ van der Vat 1997, pp. 324–25.

- ↑ Fest 1999, pp. 320–21.

- ↑ van der Vat 1997, pp. 333–34.

- ↑ Speer 1976, p. 441.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, p. 5.

- ↑ van der Vat 1997, pp. 329–30.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, pp. 664–65.

- ↑ van der Vat 1997, p. 348.

- ↑ Fest 1999, pp. 345–46.

- ↑ Fest 1999, pp. 328–29.

- 1 2 van der Vat 1997, p. 354.

- ↑ Fest 1999, p. 329.

- ↑ Asher 2003.

- ↑ Leigh 1973.

- ↑ Fest 1999, p. 337.

- ↑ van der Vat 1997, pp. 362–63.

- 1 2 Speer 1981, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Tooze 2006, Chapter 17: Albert Speer: 'Miracle Man'.

- ↑ Tooze 2006, p. 553. Cf. Sereny 1995, pp. 79–80.

- ↑ Tooze 2006, p. 555.

- ↑ van der Vat 1997, p. 75.

- ↑ Museen der Stadt Nürnberg.

- ↑ Iconic Photos, A Nazi Funeral in London.

- 1 2 3 Durth & Gutschow 1988.

- 1 2 Fest 1999, p. 116.

- ↑ Fest 1999, p. 120.

- 1 2 Fest 1999, p. 119.

- 1 2 Fest 1999, p. 124.

- ↑ van der Vat 1997, pp. 339–43.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, pp. 226–27.

- ↑ van der Vat 1997, pp. 359–61.

- ↑ Fest 2007, p. 196.

- ↑ Speer 1970, pp. 375–76.

- ↑ Speer 1970, p. 376.

- ↑ Kitchen 2015, p. 100.

- ↑ Kitchen 2015, p. 157.

- ↑ van der Vat 1997, pp. 167–68.

- ↑ van der Vat 1997, p. 168.

- ↑ Fest 1999, pp. 184–85.

- ↑ Speer 1970, pp. 312–13.

- ↑ Goldhagen 1976.

- 1 2 3 Fest 1999, pp. 185–87.

- ↑ Speer 1970, p. 313.

- ↑ van der Vat 1997, p. 169.

- ↑ Sereny 1995, p. 397.

- 1 2 Connolly 2005.

Bibliography

- Angolia, John (1978), For Fuhrer and Fatherland: Political and Civil Awards of the Third Reich, R. James Bender Publishing, ISBN 978-0-912138-16-9

- Boog, Horst; Krebs, Gerhard; Vogel, Detlef (2006). Germany and the Second World War: Volume VII: The Strategic Air War in Europe and the War in the West and East Asia, 1943–1944/5. London: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0198228899.

- Buggeln, Marc (2014). Slave Labor in Nazi Concentration Camps. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198707974.

- Conot, Robert (1983), Justice at Nuremberg, New York: Harper & Row, ISBN 978-0-88184-032-2

- Durth, Werner; Gutschow, Niels (1988), Träume in Trümmern, ("Dreams in ruins"), Vieweg Friedr. + Sohn Ver, ISBN 978-3-528-08706-7

- Fest, Joachim (1999), Speer: The Final Verdict, translated by Ewald Osers and Alexandra Dring, Harcourt, ISBN 978-0-15-100556-7

- Fest, Joachim (2007), Albert Speer: Conversations with Hitler's Architect, translated by Patrick Camiller, Polity Press, ISBN 978-0-7456-3918-5

- Fishman, Jack (1986), Long Knives and Short Memories: The Spandau Prison Story, Breakwater Books, ISBN 0-920911-00-5

- King, Henry T. (1997), The Two Worlds of Albert Speer: Reflections of a Nuremberg Prosecutor, University Press of America, ISBN 978-0-7618-0872-5

- Kitchen, Martin (2015). Speer: Hitler's Architect. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-19044-1.

- Leigh, David (October 24, 1973), "Delay, then Albert Speer is allowed in", The Times, UK, retrieved December 17, 2008

- Overy (2002) [1995]. War and Economy in the Third Reich. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-820599-6.

- Schmidt, Matthias (1984), Albert Speer: The End of a Myth, St Martins Press, ISBN 978-0-312-01709-5

- Schubert, Philipp (2006). Albert Speer: Architekt – Günstling Hitlers – Rüstungsminister – Hauptkriegsverbrecher (Thesis). Munich: GRIN Verlag. ISBN 978-3-638-59047-1.

- Sereny, Gitta (1995), Albert Speer: His Battle with Truth, Knopf, ISBN 978-0-394-52915-8

- Shirer, William (1960), The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, New York: Simon and Schuster, LCCN 60-6729

- Speer, Albert (1970), Inside the Third Reich, Translated by Richard and Clara Winston, New York and Toronto: Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-297-00015-0, LCCN 70119132 . Republished in paperback in 1997 by Simon & Schuster, ISBN 978-0-684-82949-4

- (Original German edition: Speer, Albert (1969). Erinnerungen [Reminiscences]. Berlin and Frankfurt am Main: Propyläen/Ullstein Verlag. OCLC 639475. )

- Speer, Albert (1976), Spandau: The Secret Diaries, Translated by Richard and Clara Winston, New York and Toronto: Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-02-612810-0

- (Original German edition: Speer, Albert (1975), Spandauer Tagebücher [Spandau Diaries], Berlin and Frankfurt am Main: Propyläen/Ullstein Verlag, ISBN 978-3-549-17316-9, OCLC 185306869 )

- Speer, Albert (1981), Infiltration: How Heinrich Himmler Schemed to Build an SS Industrial Empire, Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-02-612800-1

- (Original German edition: Speer, Albert (1981), Der Sklavenstaat: meine Auseinandersetzungen mit der SS [The Slave State: My Battles with the SS], Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, ISBN 978-3-421-06059-4, OCLC 7610230 )

- Tooze, Adam (2006), The Wages of Destruction: The Making & Breaking of the Nazi Economy, London: Allen Lane, ISBN 978-0-7139-9566-4

- Uziel, Daniel (2012). Arming the Luftwaffe: The German Aviation Industry in World War II. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-6521-7.

- van der Vat, Dan (1997), The Good Nazi: The Life and Lies of Albert Speer, George Weidenfeld & Nicolson, ISBN 978-0-297-81721-5

Online sources

- Asher, Edgar (November 21, 2003). "The day I met Hitler's Architect". Chicago Jewish Star. pp. 7, 9.

- Connolly, Kate (May 11, 2005), "Wartime reports debunk Speer as the good Nazi", The Daily Telegraph, UK, retrieved January 11, 2014

- Connolly, Kate (March 13, 2007), "Letter proves Speer knew of Holocaust plan", The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, retrieved May 7, 2017

- Goldhagen, Erich (March 1, 1976). "Speer Accused". Harvard Crimson. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

- "A Nazi Funeral in London", iconicphotos.wordpress.com, Iconic Photos, November 3, 2009, retrieved January 8, 2012

- "Albert Speer: The Nazi Who Said Sorry", ftvdb.bfi.org.uk, British Film Institute, 1996, retrieved January 8, 2012

- "The Paris World Exposition 1937: Monuments to dictatorship – the German and Soviet Pavilions", expo2000.de, Website of Expo 2000, Hanover, archived from the original on March 1, 2012, retrieved January 8, 2012

- "Speer cross-examination", law2.umkc.edu, University of Missouri—Kansas City, retrieved January 8, 2012

- Official website of the Memorium Nuremberg Trials, Museen der Stadt Nürnberg, retrieved November 5, 2014

Further reading

- Krier, Léon (1985). Albert Speer: Architecture, 1932–1942. Archives D'Architecture Moderne. ISBN 2-87143-006-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Albert Speer. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Albert Speer |

- "BBC Four – Audio Interviews". December 29, 1979. Archived from the original on February 20, 2003.

- Review of Albert Speer: His Battle with Truth in Foreign Affairs

- "Speer und Er" (in German). Archived from the original on March 23, 2005.

- Affidavit of Albert Speer: affidavit, sworn and signed at Munich on June 15, 1977, translated from the German original.

- 3D-stereoscopic images of New Reich Chancellery

- Newspaper clippings about Albert Speer in the 20th Century Press Archives of the German National Library of Economics (ZBW)