Jewish deicide

| Part of a series on |

| Antisemitism |

|---|

Part of Jewish history |

|

Antisemitic publications |

|

Opposition |

|

|

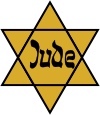

Jewish deicide is a historic belief among some in Christianity that Jewish people as a whole were responsible for the death of Jesus.[1] The antisemitic slur "Christ-killer" was used by mobs to incite violence against Jews and contributed to many centuries of pogroms, the murder of Jews during the Crusades, the Spanish Inquisition and the Holocaust.[2]

In the catechism produced by the Council of Trent, the Catholic Church affirmed that the collectivity of sinful humanity was responsible for the death of Jesus, not only the Jews.[3] In the deliberations of the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965), the Roman Catholic Church under Pope Paul VI repudiated belief in collective Jewish guilt for the crucifixion of Jesus.[4] It declared that the accusation could not be made "against all the Jews, without distinction, then alive, nor against the Jews of today".

Source of deicide charge

Justification of the charge of Jewish deicide has been sought in Matthew 27:24–25:

When Pilate saw that he was getting nowhere, but that instead an uproar was starting, he took water and washed his hands in front of the crowd. "I am innocent of this man's blood," he said. "It is your responsibility!" All the people answered, "His blood is on us and on our children!"

The verse that reads: "All the people answered, 'His blood is on us and on our children!'" is also referred to as the blood curse. In an essay regarding antisemitism, biblical scholar Amy-Jill Levine argues that this passage has caused more Jewish suffering throughout history than any other in the New Testament.[5]

According to Jeremy Cohen:

Even before the Gospels appeared, the apostle Paul (or, more probably, one of his disciples) portrayed the Jews as Christ's killers ... But though the New Testament clearly looks to the Jews as responsible for the death of Jesus, Paul and the evangelists did not yet condemn all Jews, by the very fact of their Jewishness, as murderers of the son of God and his messiah. That condemnation, however, was soon to come.[6]

As early as 167 AD, in a tract bearing the title Peri Pascha that may have been designed to bolster a minor Christian sect's presence in Sardis, where Jews had a thriving community with excellent relations with Greeks, and which is attributed to a Quartodeciman, Melito of Sardis,[7] a statement is made that appears to have transformed the charge that Jews had killed their own Messiah into the charge that the Jews had killed God himself. If so, the author would be the first writer in the Lukan-Pauline tradition to raise unambiguously the accusation of deicide against Jews.[8][9] This text blames the Jews for allowing King Herod and Caiaphas to execute Jesus, despite their calling as God's people (i.e., both were Jewish). It says "you did not know, O Israel, that this one was the firstborn of God". The author does not attribute particular blame to Pontius Pilate, but only mentions that Pilate washed his hands of guilt.[10]

St John Chrysostom made the charge of deicide the cornerstone of his theology.[11] He was the first to use the term 'deicide'[12] and the first Christian preacher to apply the word "deicide" to the Jewish nation.[13][14] He held that for this putative 'deicide', there was no expiation, pardon or indulgence possible.[15] The first occurrence of the Latin word deicida occurs in a Latin sermon by Peter Chrysologus.[16][17] In the Latin version he wrote: Iudaeos [invidia] ... fecit esse deicidas, i.e., "[Envy] made the Jews deicides".[18]

The accuracy of the Gospel accounts' portrayal of Jewish complicity in Jesus' death has been vigorously debated in recent decades, with views ranging from a denial of responsibility to extensive culpability. According to the Jesuit scholar Daniel Harrington, the consensus of Jewish and Christian scholars is that there is some Jewish responsibility, regarding not the Jewish people, but regarding only the probable involvement of the high priests in Jerusalem at the time and their allies.[1] Many scholars read the story of the passion as an attempt to take the blame off Pilate and place it on the Jews, one which might have been at the time politically motivated. It is thought possible that Pilate ordered the crucifixion to avoid a riot, for example.[19] Some scholars hold that the synoptic account is compatible with traditions in the Babylonian Talmud.[20] The writings of Moses Maimonides (a medieval Sephardic Jewish philosopher) mentioned the hanging of a certain Jesus (identified in the sources as Yashu'a) on the eve of Passover. Maimonides considered Jesus as a Jewish renegade in revolt against Judaism; religion commanded the death of Jesus and his students; and Christianity was a religion attached to his name in a later period.[21] In a passage widely censored in pre-modern editions for fear of the way it might feed into very real anti-Semitic attitudes, Maimonides wrote of "Jesus of Nazareth, who imagined that he was the Messiah, and was put to death by the court (Beth din)".[22][23][24]

David Klinghoffer argues that to attribute blame to Jewish leaders for the death of Jesus is not ipso facto anti-Semitic, since Jewish writings conserve traditions compatible with this view.[24]

Historicity of Matthew 27:24–25

_-_James_Tissot.jpg)

According to the gospel accounts, Jewish authorities in Roman Judea charged Jesus with blasphemy and sought his execution (see Sanhedrin Trial of Jesus), but lacked the authority to have Jesus put to death (John 18:31), so they brought Jesus to Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of the province, who authorized Jesus' execution (John 19:16).[25] The Jesus Seminar's Scholars Version translation note for John 18:31 adds: "it's illegal for us: The accuracy of this claim is doubtful." It is noted, for example, that Jewish authorities were responsible for the stoning of Saint Stephen in Acts 7:54 and of James the Just in Antiquities of the Jews[26] without the consent of the governor. Josephus however, notes that the execution of James happened while the newly appointed governor Albinus "was but upon the road" to assume his office. Also the Acts refers that the stoning happened in a lynch-like manner, in the course of Stephen's public criticism of Jews who refused to believe in Jesus.

It has also been suggested that the Gospel accounts may have downplayed the role of the Romans in Jesus' death during a time when Christianity was struggling to gain acceptance among the then pagan or polytheist Roman world.[27] Matthew 27:24–25 reads:

So when Pilate saw that he prevailed nothing, but rather that a tumult was arising, he took water, and washed his hands before the multitude, saying, I am innocent of the blood of this righteous man; see ye [to it]. And all the people answered and said, His blood [be] on us, and on our children.

This passage has no counterpart in the other Gospels and some scholars see it as probably related to the destruction of Jerusalem in the year 70 A.D.[28] Ulrich Luz describes it as "redactional fiction" invented by the author of the Gospel of Matthew.[29] Some writers, viewing it as part of Matthew's anti-Jewish polemic, see in it the seeds of later Christian antisemitism.[30]

In his 2011 book, Pope Benedict XVI, besides repudiating placing blame on the Jewish people, interprets as not referring to the whole Jewish people the passage found in the Gospel of Matthew which has the crowd saying, "Let his blood be upon us and upon our children".[31][32]

Historicity of Barabbas

Some biblical scholars including Benjamin Urrutia and Hyam Maccoby go a step further by not only doubting the historicity of the blood curse statement in Matthew but also the existence of Barabbas.[33] This theory is based on the fact that Barabbas's full name was given in early writings as Jesus Barabbas,[34] meaning literally Jesus, son of the father. The theory is that this name originally referred to Jesus himself, and that when the crowd asked Pilate to release "Jesus, son of the father" they were referring to Jesus himself, as suggested also by Peter Cresswell.[35][36] The theory suggests that further details around Barabbas are historical fiction based on a misunderstanding. The theory is disputed by other scholars.[37]

Liturgy

Eastern Christianity

The Holy Friday liturgy of the Orthodox Church, as well as the Byzantine Rite Roman Catholic churches, uses the expression "impious and transgressing people",[38] but the strongest expressions are in the Holy Thursday liturgy, which includes the same chant, after the eleventh Gospel reading, but also speaks of "the murderers of God, the lawless nation of the Jews",[39] and, referring to "the assembly of the Jews", prays: "But give them, Lord, their reward, because they devised vain things against Thee."[40]

Western Christianity

A liturgy with a similar pattern but with no specific mention of the Jews is found in the Improperia of the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church. In the Anglican Church, the first Anglican Book of Common Prayer did not contain this formula, but it appears in later versions, such as the 1989 Anglican Prayer Book of the Anglican Church of Southern Africa, as The Solemn Adoration of Christ Crucified or The Reproaches.[41] Although not part of Christian dogma, many Christians, including members of the clergy, preached that the Jewish people were collectively guilty for Jesus' death.[4]

Repudiation

The French-Jewish historian and Holocaust survivor Jules Isaac, in the aftermath of World War II, played a seminal role in documenting the anti-Semitic traditions in Catholic Church thinking, instruction and liturgy. The move to draw up a formal document of repudiation gained momentum after a private audience Isaac obtained with Pope John XXIII in 1960.[42] In the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965), the Catholic Church under Pope Paul VI issued the declaration Nostra aetate ("In Our Time"), which among other things repudiated belief in the collective Jewish guilt for the crucifixion of Jesus.[4] Nostra aetate stated that, even though some Jewish authorities and those who followed them called for Jesus' death, the blame for what happened cannot be laid at the door of all Jews living at that time, nor can the Jews in our time be held guilty. It made no explicit mention of Matthew 27:24–25, but only of John 19:6.

On November 16, 1998, the Church Council of Evangelical Lutheran Church in America adopted a resolution prepared by its Consultative Panel on Lutheran-Jewish Relations urging any Lutheran church presenting a Passion play to adhere to their Guidelines for Lutheran-Jewish Relations, stating that "the New Testament … must not be used as justification for hostility towards present-day Jews", and that "blame for the death of Jesus should not be attributed to Judaism or the Jewish people."[43][44]

Pope Benedict XVI also repudiates the Jewish deicide charge in his 2011 book Jesus of Nazareth, in which he interprets the translation of "ochlos" in Matthew to mean the "crowd", rather than to mean the Jewish people.[31][45]

See also

References

- 1 2 Greenspoon, Leonard; Hamm, Dennis; Le Beau, Bryan F. (1 November 2000). The Historical Jesus Through Catholic and Jewish Eyes. A&C Black. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-56338-322-9.

- ↑ Singer, Thomas; Kimbles, Samuel L. (31 July 2004). The Cultural Complex: Contemporary Jungian Perspectives on Psyche and Society. Routledge. p. 33. ISBN 1-135-44486-2.

- ↑ Norman C. Tobias, Jewish Conscience of the Church: Jules Isaac and the Second Vatican Council, Springer, 2017 p.115.

- 1 2 3 "Nostra Aetate: a milestone - Pier Francesco Fumagalli". Vatican.va. Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- ↑ Fredriksen, Paula; Reinhartz, Adele (2002). Jesus, Judaism, and Christian Anti-Judaism: Reading the New Testament After the Holocaust. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-664-22328-1.

- ↑ Jeremy Cohen, Christ Killers: The Jews and the Passion from the Bible to the Big Screen, Oxford University Press 2007. p.55.

- ↑ Lynn Cohick, 'Melito of Sardis's "PERI PASCHA" and Its "Israel",' The Harvard Theological Review, Vol. 91, No. 4 (Oct., 1998), pp. 351-372.

- ↑ Abel Mordechai Bibliowicz, Jews and Gentiles in the Early Jesus Movement: An Unintended Journey, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013 pp.180–182.

- ↑ Christine Shepardson, Anti-Judaism and Christian Orthodoxy: Ephrem's Hymns in Fourth-century Syria, CUA Press 2008 p.27.

- ↑ "On the passover" pp. 57, 82, 92, 93 from Kerux: The Journal of Northwest Theological Seminary

- ↑ Gilman, Sander L.; Katz, Steven T. (1 March 1993). Anti-Semitism in Times of Crisis. NYU Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-8147-3056-0.

- ↑ Fred Gladstone Bratton, [The Crime of Christendom: The Theological Sources of Christian Anti-Semitism], Beacon Press, 1969 p. 85.

- ↑ David F. Kessler (12 October 2012). The Falashas: A Short History of the Ethiopian Jews. Routledge. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-136-30448-4.

- ↑ Malcolm Vivian Hay [Thy brother's blood: the roots of Christian anti-Semitism], Hart Pub. Co., 1975 p.30.

- ↑ Flannery, Edward H. (1985). The Anguish of the Jews: Twenty-three Centuries of Antisemitism. Paulist Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-8091-4324-5.

- ↑ Wolfram Drews, The unknown neighbour: the Jew in the thought of Isidore of Seville, Brill, 2006 p.187.

- ↑ Charleton Lewis and Charles Short, Latin Dictionary Latin Dictionary

- ↑ Sermons of Peter Chrysologus, vol. 6, p. 116, "Sermo CLXXII", at Google Books

- ↑ Kierspel, Lars (2006). The Jews and the World in the Fourth Gospel: Parallelism, Function, and Context. Mohr Siebeck. p. 7. ISBN 978-3-16-149069-9.

- ↑ Laato, Antii; Lindqvist, Pekka (14 September 2010). Encounters of the Children of Abraham from Ancient to Modern Times. BRILL. p. 152. ISBN 90-04-18728-6.

The Babylonian Talmud, as distinct from the Palestinian Talmud, conserves these traditions, arguably, because Palestine was under Christian domination, whereas the Sassanid Empire, which hosted major academies of the Jewish diaspora, viewed Christianity inimicably. The different political situation in the latter allowed for freer dissent

- ↑ Davidson, Herbert (9 December 2004). Moses Maimonides: The Man and His Works. Oxford University Press. pp. 293, 321. ISBN 978-0-19-534361-8.

- ↑ Goodman, Micah (1 May 2015). Maimonides and the Book That Changed Judaism: Secrets of The Guide for the Perplexed. U of Nebraska Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-8276-1197-9.

- ↑ Kellner, Menachem Marc (28 March 1996). Maimonides on the "Decline of the Generations" and the Nature of Rabbinic Authority. SUNY Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-7914-2922-8.

- 1 2 Klinghoffer, David (18 December 2007). Why the Jews Rejected Jesus: The Turning Point in Western History. Potter/TenSpeed/Harmony. pp. 3, 72–73. ISBN 978-0-307-42421-1.

To say that Jewish leaders were instrumental in getting Jesus killed is not anti-Semitic. Otherwise we would have to call the medieval Jewish sage Moses Maimonides anti-Semitic and the rabbis of the Talmud as well.

- ↑ The Historical Jesus Through Catholic and Jewish Eyes by Bryan F. Le Beau, Leonard J. Greenspoon and Dennis Hamm (Nov 1, 2000) ISBN 1563383225 pages 105-106

- ↑ "20.9.1". Earlyjewishwritings.com. Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- ↑ Anchor Bible Dictionary vol. 5. (1992) pg. 399–400. Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc.

- ↑ Craig Evans, Matthew (Cambridge University Press, 2012) page 455.

- ↑ Ulrich Luz, Studies in Matthew (William B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2005) page 58.

- ↑ Graham Stanton, A Gospel for a New People, (Westminster John Knox Press, 1993) page 148.

- 1 2 Joseph Ratzinger, Pope Benedict XVI (2011). Jesus of Nazareth. Retrieved 2011-04-18.

- ↑ "Pope Benedict XVI Points Fingers on Who Killed Jesus". 2011. Retrieved 2011-04-18.

- ↑ Urrutia, Benjamin. "Pilgrimage", The Peaceable Table (October 2008)

- ↑ Evans, Craig A. (2012). Matthew (New Cambridge Bible Commentary). Cambridge University Press. p. 453. ISBN 978-0521011068.

- ↑ Peter Cresswell, Jesus The Terrorist, 2009

- ↑ Peter Cresswell, The Invention of Jesus: How the Church Rewrote the New Testament, 2013

- ↑ Purcell, J. Q. (1 June 1985). "Case of the Duplicate Pseudo-Barabbas, Cont". Letter to the Editor. The New York Times. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ↑ Ware, Metropolitan Kallistos and Mother Mary. The Lenten Triodion. St. Tikhon's Seminary Press, 2002, p. 612 (second stichos of Lord, I Have Cried at Vespers on Holy Friday)

- ↑ Ware, Metropolitan Kallistos and Mother Mary. The Lenten Triodion. St. Tikhon's Seminary Press, 2002, p. 589 (third stichos of the Beatitudes at Matins on Holy Friday)

- ↑ Ware, Metropolitan Kallistos and Mother Mary. The Lenten Triodion. St. Tikhon's Seminary Press, 2002, p. 586 (thirteenth antiphon at Matins on Holy Friday). The phrase "plotted in vain" is drawn from Psalm 2:1.

- ↑ An Anglican Prayer Book (1989) Church of the Province of Southern Africa

- ↑ Tapie, Matthew A. (26 February 2015). Aquinas on Israel and the Church: Aquinas on Israel and the Church. James Clarke & Co. pp. 12–14. ISBN 978-0-227-90396-4.

- ↑ Evangelical Lutheran Church in America "Guidelines for Lutheran-Jewish Relations" November 16, 1998

- ↑ World Council of Churches "Guidelines for Lutheran-Jewish Relations" in Current Dialogue, Issue 33 July, 1999

- ↑ "Pope Benedict XVI Points Fingers on Who Killed Jesus". March 2, 2011. Retrieved 2012-09-28.

While the charge of collective Jewish guilt has been an important catalyst of anti-Semitic persecution throughout history, the Catholic Church has consistently repudiated this teaching since the Second Vatican Council.