Saurashtra people

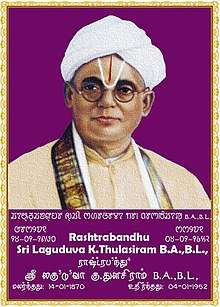

Saurashtrian Nobleman of 19th Century | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 2 million[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka | |

| Languages | |

| Saurashtra (mother tongue), Tamil | |

| Religion | |

|

| |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Pancha-Gauda Brahmins, Pattusali, Tamil people |

The Saurashtra people (alternate spellings: Sourashtra, Sowrashtra, Sourashtri), also known as Patnūlkarar (colloquially called Palkar), or simply Saurashtrians,[2][3] are an Indo-Aryan ethno-linguistic Hindu community of South India who speak the Saurashtra language, an Indo-Aryan language, predominantly residing in the Indian states of Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka.[4]

Saurashtrians are Brahmins,[5][6] and are also referred to as Saurashtra Brahmins.[7][8][2][9][10] They were a prominent industrious and prosperous mercantile community of merchants and weavers in southern India until the 20th century.[11][12]

Saurashtrians are generally vegetarian[13] and wear the sacred thread further like all traditional orthodox Brahmins, they are also classified based on their gotra, or patrilineal descent, majority of the people are Vaishnavas, though there is a significant proportion of Shaivas as well. They are prominently known by their unique family names and also use the titles Sharma,[14] Rao,[15] Iyer[15] and Iyengar[16] as their surnames but belong to linguistic minorities.[17]

Etymology

The Tamil name by which these people are also known in Tamil Nadu is Patnūlkarar,[18] which means silk-thread people,[19] mostly silk-thread merchants and silk weavers[20] who speak "Patnūli" or "Palkar" or "Saurashtra", a dialect of Gujarati.[4][21]

These people are first mentioned as Pattavayaka, the Sanskrit equivalent of Patnūlkarar in the Mandasor (present day Madhya Pradesh) inscriptions of Kumaragupta I belonging to the 5th century AD. They are also mentioned by the same name in the Patteeswaram inscriptions of Thanjavur belonging to the mid 16th century AD[22] and in the inscriptions of Rani Mangammal of Madurai belonging to the 17th century AD.[6][5][23][24][21]

Origin

The Bhagavata Purana mentions that the ancient Abhiras were the rulers of Saurashtra Kingdom and Avanti Kingdom and they were followers of the Vedas, who worshiped Vishnu as their supreme deity.[25] These ancient provinces as depicted in the epic literature of Mahabharata roughly corresponds to the present day Saurashtra region of southern Gujarat and Malwa region of Madhya Pradesh.

Their origin is Dwarka, land of Lord Krishna,[2] the origin of the name date backs to the time when the ancestors of these people inhabited the Lata region of Saurashtra in southern Gujarat.[5][6][26] Saurashtrians are originally Gauda Brahmins and belong to Pancha-Gauda Brahmins.[5][6] After their southward migration they have been called as Saurashtra Brahmins.[2][27][28][18][29] They had their original homes in present-day Gujarat and migrated to South India over a millennium ago.[30] They are currently scattered over various places of Tamil Nadu and are mostly concentrated in Madurai, Thanjavur and Salem Districts.[31]

History

Saurashtrians migrated from southern Gujarat in 11th century AD after the fall of Somnath Temple[32] when Mahmud of Ghazni invaded India. It is said that the Saurashtrians lived in Devagiri, the present day Daulatabad of Maharashtra during the regime of the Yadava kings up to 13th century AD. After the fall of Yadavas in 14th century AD they moved to Vijayanagar Empire by the invitation of the Kings. The expansion of Vijayanagar empire brought the Saurashtrians into South India in 14th century AD, since they were highly skilled manufacturers of fine silk garments and were patronized by the Kings and their families.[33] After the fall of Vijayanagar empire they were welcomed by the Nayak Kings of Thanjavur during mid 16th century AD[22] and Madurai during 17th century AD and were allowed to settle near the Thirumalai Nayakkar Palace.[1][34][35][36][37]

Social Division

Occupation, sects and gotras

From the view point of an outsider the community may be seen as a homogenous one. However, in reality many subdivisions exist among them at various levels. Occupationally, the Saurashtrians may be classified broadly as priests, merchants and weavers.

Sects

The Saurashtrians may further be divided into three sects on a religious basis. viz.,

- Vaishnavites, who wear the vertical Vaishnavite mark, and call themselves northerners;

- Smarthas, who wear horizontal marks;

- Madhvas, who wear gopi (Sandal paste) as their sect mark.

All the above three divisions intermarry and interdine, and the religious difference does not create a distinction in the community. The Saurashtrians classify their ancestors as originally belonging to the two lines of Thiriyarisham and Pancharisham descent groups. Their religion is Hinduism, they follow Yajurveda,[6] and they were originally Madhvas. After their settlement in Southern India, some of them, owing to the preachings of Sankaracharya and Ramanujacharya, were converted into Saivites and Vaishnavites respectively.[16]

Gotras

Saurashtrians, like all other Hindu Brahmins, trace their paternal ancestors to one of the seven or eight sages, the saptarishis. They classify themselves into gotras, named after the ancestor rishi and each gotra consists of different family names. The gotra was inherited from Guru at the time of Upanayana, in ancient times, so it is a remnant of Guru-shishya tradition, but since the tradition is no longer followed, during Upanayana ceremony father acts as Guru of his son, so the son inherits his father's gotra. The entire community consists of 64 gotras.

Saurashtrians belong to following gotras.

- Agasthiya

- Angeerasa

- Aruni

- Asitha

- Athreya

- Bhageeratha

- Bharadwaja

- Bhargava

- Chyavana

- Dadheecha

- Devala

- Durvasa

- Galava

- Gargeya

- Gowthama

- Gowthsa

- Haritha

- Hothra

- Idhmavaaha

- Jabali

- Jaimuni

- Jamadagni

- Jannhu

- Kanva

- Kavasa

- Khasyaba

- Koumanda

- Koundinya

- Kousika

- Kupitha

- Maandavya

- Mandabala

- Mareesi

- Markandeya

- Mathanga

- Medhatithi

- Moudgalya

- Mounjanya

- Mythreya

- Ourva

- Pailava

- Parasara

- Pippala

- Pramathi

- Saaliga

- Sakthi

- Sandialya

- Sarabhanga

- Soomantha

- Soubari

- Sounaka

- Srivathsa

- Upamanyu

- Usena

- Uthanga

- Vaathsaayana

- Vaisampayana

- Valmiki

- Vamadeva

- Vasista

- Vathsa

- Viswamithra

- Vyasa

Marriage within common gotra is strictly prohibited.[21][31][16][37]

Culture

Saṃskāras, rituals and Festivals

Saurashtrians have been traditionally an orthodox and closely knit community. They are essentially northern in their customs, manners and social structure. Traditionally, joint family was a social and economic unit for them. Moreover, the pattern of joint family helped them transmit their traditional culture to the younger generations.[37][35]

Saṃskāras

Saurashtrians strictly adhere to all the Ṣoḍaśa Saṃskāra or 16 Hindu Samskaras,[28] out of which, the main social customs among them consist of six social ceremonies in the life of a person. (1) the naming ceremony; (2) the sacred thread ceremony; (3) puberty; (4) marriage; (5) the attainment of the age of sixty; (6) the funeral rites.[37][35][38]

The rites that are performed following the birth of a child are known as jathakarma. The naming ceremony in particular is known as namakaranam. The main aim of performing these birth ceremonies is to purify and to safeguard the child from diseases. These rituals are believed to check the ill effects of Planetary movement. The above rites were carried out on the eleventh day after birth of the child. Grandfather's name was much preferred for a male child and the name of a female deity was suggested for female child.[37]

The vaduhom ceremony (Sacred Thread ceremony) of Saurashtrians is basically the upanayanam ceremony. This ceremony is exceedingly important among them. This is performed between seventh and thirteenth years. In rare cases when the sacred thread ceremony was not held in the young ages, it would be performed at the time of marriage. The goal of this ceremony was to highlight their Brahminical status. During this ceremony there was much feasting and entertainment which lasted for four days.[37]

Among the Saurashtrians, attaining puberty was the greatest event in a girl's life. They also perform a pre-puberty marriage.[38]

The wedding ceremony lasted 11 days with as many as 36 rituals. All these rituals were conducted by the Saurashtrian priests who were a separate clan in the community.[2] The Saurashtrians have their own marital arrangements. Before a marriage is fixed, a long negotiation takes place between the parents of both partners. Being traditional orthodox Hindus they are very much particular in matching the horoscope of the couple. A man may claim his maternal uncle's daughter as his wife, and polygamy is permitted. Girls get married at an early age. Marriage within common gotra is strictly prohibited among them.[31][16][28][38]

Death rituals are termed as abarakkirigai or andhiyaeshti in the Saurashtrian community. Andhiyaeshti means the last or final fire. These rituals are carried out by the eldest son of the deceased. In case of no son, the relatives carry out the last rites. Kartha is the name given to the one who carries out this rite. The performance of the rite signifies the belief that the life is continuous and does not end by one's death. Further, the deceased are believed to reach the level of the deities. The period of mourning lasts for ten days, but it is repeated every year in the form of sraddha ceremonies.[28][35]

Festivals

The Saurashtrians are of a religious bent of mind and they value morality and high character. The chief divinity of Saurashtrians is Venkateshwara of Tirupati. Among other Gods they worshipped Sun God, Rama etc. They made regular visits to Meenakshi temple. They celebrate Kolattam, Chithirai festival and Ramanavami with great enthusiasm, and observe Deepawali, Ganesh Chathurthi, Dussehra, Vaikunta Ekadasi and Avani Avittam as important religious days.[2] Their present social customs differ markedly from the traditional pattern and bear a close resemblance to those of Tamils. Only some orthodox well-to-do merchant families stick to their older customs.[31][16][36][37][38]

Demographics

There are three group of Saurashtrians living in Tamil Nadu. First migrants came to Salem and settled there, second group of migrants settled in Thanjavur and its surrounding places and later third group of migrants settled in Madurai and its surrounding places. Saurashtrians maintain a predominant presence in Madurai, a city, also known as 'Temple City' in the southern part of Tamil Nadu. Though official figures are hard to come by, it is believed that the Saurashtrian population is anywhere between one-fourth and one-fifth of the city's total population.

They are present in significant numbers in Ambur, Ammapettai, Ammayappan, Aranthangi, Arni, Ayyampettai, Bhuvanagiri, Chennai, Dharasuram, Dindigul, Erode, Kancheepuram, Kanyakumari, Karaikudi, Kottar, Krishnapuram, Kumbakonam, Namakkal, Nilakottai, Palani, Palayamkottai, Paramakudi, Parambur, Periyakulam, Puducherry, Pudukkottai, Rajapalayam, Ramanathapuram, Salem, Thanjavur, Thirubhuvanam, Thiruvaiyaru, Thiruvarur, Thuvarankurichi, Tirunelveli, Tiruvannamalai, Illuppur, Thiruvappur, Trichy, Vaniyambadi, Veeravanalur, Vellanguli, Vellore, Walajapet in Tamil Nadu.[4]

They are also present in Kerala, Bengaluru in Karnataka[4] and Tirupati, Vijayanagaram, Hyderabad, Vijayawada, Nellore, Srikakulam, Vishakapatnam in Andhra Pradesh[4] is said to house several Saurashtrian families, known as Pattusali.[39]

Language

The mother tongue of Saurashtrians is Saurashtra (alternate names and spellings: Sourashtra, Sowrashtra, Sourashtri, Palkar), a dialect of Gujarati with the amalgamation of present-day Sanskrit, Hindi, Marathi, Konkani, Kannada, Telugu & Tamil but all of them are bilingual[14] and can speak either Tamil or Telugu or one of the local languages.

Saurashtra, a offshoot of Sauraseni Prakrit,[14] once spoken in the Saurashtra region of Gujarat, is spoken today chiefly by the population of Saurashtrians settled in parts of Tamil Nadu.[40] With the Saurashtrian language being the only Indo-Aryan language employing a Dravidian script and is heavily influenced by the Dravidian languages such as Tamil and Telugu. However, Census of India places the language under Gujarati.

Genetics

Organisation

The prominent leaders among the community arose in the late 19th century and felt the need of organizing the community. At first, the Madurai Saurashtra Sabha was formed in the year 1895 and it was formally registered in the year 1900 with many objectives. The formation of this Sabha was the first step towards social mobilization. The Sabha's administration is carried out by elected Councillors and office bearers. It has its own rules and regulations regarding holding of elections, rights and duties of office bearers and celebration of social functions. The election to the Sabha is held once in three years. The social life of the Saurashtrians is controlled almost wholly by the Saurashtra Sabha. This organisation is a committee of the leading men of the community, which manages and controls all the schools and public institutions, the temple and its worship, and all political, religious, and social questions among the Saurashtrians.

The Saurashtra Madhya (central) Sabha, which has its headquarters at Madurai now remains as the cultural center for all the Saurashtrians living in Tamil Nadu. Many well-to-do merchants and philanthropists of the community have contributed substantially to the growth of these institutions. Today, the Saurashtrians are represented in white collar jobs and professions in large numbers.[31][2][41]

In 2009, Narendra Modi, the 16th Prime Minister of India, inaugurated the Research Institute of Saurashtra Heritage and Immigration (RISHI), a project in association with Saurashtra University, Rajkot.[32]

Politics

In the second decade of 20th century, the Saurashtrians emerged as a dominant group in social and political life of Madras Presidency. The Saurashtrians emerged as the dominant social group because of their collective mobilization, intellectual leadership, education, wealth, trade and enterprise. There are several instances when the leaders of the community organised the weavers and made social and economic protests. The well-to-do merchants of the community made donations to TNCC for Salt Satyagraha and welcomed any form of Swadeshi agitation which favoured Indian cloth.[42]

The leaders who came to lead the community were not always from the upper class. L.K. Thulasiram, who led the community in Madurai, was not born into the aristocratic family. With his own efforts he travelled abroad which brought prosperity to himself and to the community in general. Thulasiram at first supported the non-Brahmin movement in Tamil Nadu. When he earned the displeasure of his community members who were fighting for Brahminical status, he changed his mind and supported the cause of his own people.[42] He got elected as Municipal Chairman in 1921 amidst a fierce contest. During his tenure he brought many reforms within the community. He introduced free mid-day meal scheme in community owned school for the first time in the country which was later emulated by the Government of Tamil Nadu during the period of K. Kamaraj in the name of noon-meal scheme in Government schools.[41] When he lost his hold in Municipal Council, he became a prominent organizer of non-cooperation movement. Later he impressed the Congress Party and became the leader of the merchants. In this capacity he strove hard to raise the prestige and position of his community.[43]

N.M.R. Subbaraman, another leader of the community, financed and led the Civil Disobedience Movement In Madurai from 1930-32. He worked for the advancement of the depressed classes. He, along with A. Vaidyanatha Iyer, organised a temple entry conference and helped the people of the depressed classes to enter Meenakshi Amman Temple. He was involved in the Bhoodan movement and donated his 100 acres of land to the movement. He contributed to establishing the first Gandhi Memorial Museum in Madurai.[44] Later he expressed his dissatisfaction with Civil Disobedience. He felt unhappy about the expenditure incurred on the agitational activities. He mobilized his followers into Municipal politics with the help of Venkatamarama Iyer faction under the Congress banner.[43]

Portrayal in popular media

- In a 2014 Tamil movie Naan Than Bala, Vaishali (portrayed by Shwetha Bandekar), one of the main characters, her father speaks Saurashtra, thereby suggesting that she is from a Saurashtrian family.[45]

- In an another 2014 Tamil comedy-gangster movie Jigarthanda, Kayalvizhi (portrayed by Lakshmi Menon), the heroine and her mother (portrayed by Ambika) are found speaking in Saurashtra, thereby suggesting that they are Saurashtrians.[46]

Notable people

Cinema

- T. M. Soundararajan (1924–2013), Tamil Playback singer

- P. V. Narasimha Bharathi (1924–1978), Tamil film Actor[47]

- Kaka RadhaKrishnan (1925–2012), Veteran actor

- S. C. Krishnan (1929–1983), Tamil Playback singer

- M. S. Sundari Bai (1923–2006), Tamil film Actress

- T. K. Ramachandran, Tamil film Actor

- M. N. Rajam, Tamil film Actress[47]

- A. L. Raghavan, Tamil Playback singer[47]

- Vennira Aadai Nirmala, Tamil film Actress[47]

- Seetha, Tamil film Actress[47]

- Jagadeesh Kanna, Tamil film Actor

Literature

- Sankhu Ram (1907–1976), Saurashtrian poet (translated the Tirukkural into Saurashtra)

- M. V. Venkatram (1920–2000), Tamil writer (Sahitya Akademi Award granted for his Kathukal Novel)

Politics

- N. M. R. Subbaraman (1905–1983), Tamil politician & Freedom fighter

- S. K. Balakrishnan, Tamil politician & Former Mayor

- A. G. Subburaman, Tamil politician & Former MP

- A. G. S. Ram Babu, Tamil politician & Former MP[48]

Military

- Netaji Palkar (1620–1681), the chief commander of Chatrapathy Shivaji

Educational Institutions

Temples

See also

References

- 1 2 Vandhana, M. (2014-04-14). "Madurai's Sourashtrians are a disappointed lot". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2018-02-19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 M.R, Aravindan (2003). "The Hindu : Where they have come to stay". www.thehindu.com. Retrieved 2018-02-19.

- ↑ Shanmugam, Kavitha (2014). "Girls Don't Say AYAYYO Here Anymore". www.telegraphindia.com. Retrieved 2018-09-02.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Saurashtra". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2018-02-20.

- 1 2 3 4 Jan Lucassen, Leo Lucassen (2014-03-27). Globalising Migration History: The Eurasian Experience (16th-21st Centuries). BRILL. pp. 109–112, 121. ISBN 9789004271364.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ramaswamy, Vijaya (2017-07-05). Migrations in Medieval and Early Colonial India. Routledge. pp. 172–190. ISBN 9781351558242.

- ↑ Kolappan, B. (2016-01-07). "20 more keerthanas of Tyagaraja's disciple discovered". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2018-09-18.

- ↑ "Saurashtrians - The Genuine Aryans (Part Three)". IndiaDivine.org. Retrieved 2018-02-10.

- ↑ "The Hindu : Entertainment Chennai / Personality : Illustrious disciple of saint-poet". www.thehindu.com. 2005. Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- ↑ Suryanarayana, M.; Reddy, P. Sudhakar; Gangadharam, V. (2002). Indian Society: Continuity, Change, and Development : in Honour of Prof. M. Suryanarayana. Commonwealth Publishers. pp. 93, 95, 99. ISBN 9788171696932.

- ↑ Mahadevan, Raman (1984). Entrepreneurship and Business Communities in Colonial Madras 1900-1929, in D. Tripathy (Ed.) Business Communities of India. Monohar Publications. pp. 210–225.

- ↑ Lucassen, Jan; Moor, Tine De; Zanden, Jan Luiten van (2008). The Return of the Guilds:. Cambridge University Press. p. 115. ISBN 9780521737654.

- ↑ Parmar, Vijaysinh (2016). "Gujaratis who settled in Madurai centuries ago brought with them a unique language - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 2018-03-21.

- 1 2 3 Vannan, Gokul (2016-06-09). "Custodians safeguard Saurashtra language". Deccan Chronicle. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- 1 2 Arterburn, Yvonne J. (1982). The loom of interdependence: silkweaving cooperatives in Kanchipuram. Hindustan Pub. Co. pp. 44, 47, 50–53.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Edgar Thurston, K. Rangachari, (1909). "Castes and Tribes of South India". Madras: Government Press. pp. 160–176.

- ↑ "Minority front to field 8 candidates". The Hindu. 2009-04-29. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2018-02-28.

- 1 2 Singh, Mahavir (2005). Home Away from Home: Inland Movement of People in India. Maulana Abul Kalam Azad Institute of Asian Studies. pp. 105–106. ISBN 9788179750872.

- ↑ Sivarajah, Padmini (2016). "Believe it or not, the Gujarati vote is key in Madurai South - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- ↑ M, Mhaiske, Vinod; K, Patil, Vinayak; S, Narkhede, S. (2016-03-01). Forest Tribology And Anthropology. Scientific Publishers. p. 148. ISBN 9789386102089.

- 1 2 3 Jensen, Herman (2002). Madura Gazetteer. Cosmo Publications. pp. 109–112. ISBN 9788170209690.

- 1 2 Sethuraman, K. R. (1977). Tamilnatil Saurashtrar : Muzhu Varalaru (in Tamil). Saurashtra Cultural Academy. pp. 10–15.

- ↑ Singh, Kumar Suresh; India, Anthropological Survey of (2001). People of India. Anthropological Survey of India. p. 1303. ISBN 9788185938882.

- ↑ Heredia, Rudolf C.; Ratnagar, Shereen (2003-01-01). Mobile, and Marginalized Peoples: Perspectives from the Past. Manohar. p. 93. ISBN 9788173044977.

- ↑ Yadav, J. N. Singh (1997-10-01). Yadavas Through the Ages. Sharada Publishing House. p. 146. ISBN 9788185616032.

- ↑ J.S. Venkatavarma, Sourashtra Charitra Sangraham (Madura, 1915)

- ↑ Dvivedula, Anamtapadmanaabham (2005). "Aaraamadraavida Vamsacharitra (Arama Dravida) Brahmins, Mana Sanskriti". www.vepachedu.org. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- 1 2 3 4 Joseph, Ashish (2016). "Meet three of Chennai's oldest communities from the north - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

- ↑ Krishnan, Lalithaa (2016-04-28). "Like a cloud of steam". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2018-04-02.

- ↑ Diep, Francie (2013). "How A Gene For Fair Skin Spread Across India". Popular Science. Retrieved 2018-04-02.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The Saurashtra Community in Madurai, South India", Albert James Saunders, The American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 32, No. 5 (Mar. 1927) pp. 787-799, published by: The University of Chicago Press.

- 1 2 Rohith, S. Mohammed (2014-05-28). "Sourashtra community in celebration mode". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ↑ Srikumaran, K. (2005). Theerthayathra: A Pilgrimage Through Various Temples. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. pp. 125–126. ISBN 9788172763633.

- ↑ T K, Ramesh. "The Unwritten History of the Saurashtrians of South India". Boloji. Retrieved 2018-02-19.

- 1 2 3 4 Randle, H.N (1949). The Saurashtrians of South India. Madurai: K. V. Padmanabha Iyer.

- 1 2 Gopalakrishnan, M S (1966). A Brief Study of the Saurashtra Community in the Madras State. Madras: The Institute of Traditional Cultures Madras. p. 42.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Dave, Ishvarlal Ratilal (1976). The Saurashtrians in South India: Their Language, Literature, and Culture. Saurashtra University.

- 1 2 3 4 Učida, Norihiko (1979). Oral literature of the Saurashtrans. Simant Publications India.

- ↑ People of India: A - G.- Volume 4. Oxford Univ. Press. 1998. p. 3189. ISBN 9780195633542.

- ↑ Kolappan, B. (2016-12-24). "Akademi award for TN writers who revived Sourashtra literature". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2018-03-08.

- 1 2 Kavitha, S.S (2007-10-08). "Standing tall in all fronts". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2018-03-24.

- 1 2 Irschick, Eugene F.; Studies, University of California, Berkeley Center for South and Southeast Asia (1969). Politics and Social Conflict in South India: The Non-Brahman Movement and Tamil Separatism, 1916-1929. University of California Press. pp. 9, 138.

- 1 2 Backer, C.J (1976). The Politics of South India, 1920-1937. New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House. pp. 143–217.

- ↑ "Throwing light on the life of `Madurai Gandhi'". The Hindu. 2006-08-20. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

- ↑ Rangan, Baradwaj (2014-06-14). "Naan Than Bala: Friends with benedictions". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2018-09-29.

- ↑ "Jigarthanda Movie Review". The Times of India. 2016-05-29. Retrieved 2018-10-04.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Saravanan, T. (2016-11-30). "Linguistic confluence". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2018-04-15.

- ↑ "Weaving their way into Madurai - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 2018-02-21.

Further reading

- Chintaman, Vinayak Vaidya (1924). History of Medieval Hindu India: (being a History of India from 600 to 1200 A.D.). Oriental Book Supplying Agency.

- Bulletin of the Institute of Traditional Cultures. University of Madras. 1967. p. 71.

- K.V, Padmanabha Iyer (1942). A History of the Sourashtras in Southern India. Sourashtra Literary Society (Madras, India).

- Ganapathy Palanithurai, R. Thandavan (1998). Ethnic movement in transition: ideology and culture in a changing society. Kanishka Publishers, Distributors. p. 34. ISBN 9788173912474.