San Diego State University

| |

Former names |

San Diego Normal School (1897–1923) San Diego State Teachers College (1923–1935) San Diego State College (1935–1972) California State University, San Diego (1972–1974) |

|---|---|

| Motto | Leadership Starts Here |

| Type |

Public research university Space Grant University |

| Established | March 13, 1897 |

| Endowment | $289 million (2018)[1] |

| Budget | $894.2 million (2017)[2] |

| President | Adela de la Torre |

| Provost | Joseph F. Johnson, Jr. (interim) |

Academic staff | 1,491 (Fall 2013)[3] |

Administrative staff | 1,591 (Fall 2013)[3] |

| Students | 34,828 (Fall 2018)[4] |

| Undergraduates | 30,165 (Fall 2018)[4] |

| Postgraduates | 4,663 (Fall 2018)[4] |

| Location |

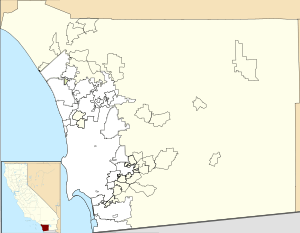

San Diego, California Coordinates: 32°46′31″N 117°04′20″W / 32.77528°N 117.07222°W[5] |

| Campus | 283 acres (1.15 km2) Urban |

| Colors |

Scarlet and Black[6] |

| Athletics | NCAA Division I FBS |

| Nickname | Aztecs |

Sporting affiliations | |

| Mascot | Aztec warrior |

| Website |

www |

|

| |

|

San Diego State College | |

| |

| Location |

5500 Campanile Dr., San Diego, California |

| Area | 283 acres (114.5 ha) |

| Architectural style | Mission/Spanish Revival |

| NRHP reference # | 97000924[7] |

| CHISL # | 798 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | September 4, 1997 |

| Designated CHISL | 1964[8] |

San Diego State University (SDSU) is a public research university in San Diego, California, and is the largest and oldest higher education institution in San Diego County. Founded in 1897 as San Diego Normal School, it is the third-oldest university in the 23-member California State University (CSU). SDSU has a Fall 2016 student body of 34,688 and an alumni base of more than 280,000.[9]

The Carnegie Foundation has designated San Diego State University a "Doctoral University" with "Higher Research Activity."[10] In the 2015–16 fiscal year, the university obtained $130 million in public and private funding—a total of 707 awards—up from $120.6 million the previous fiscal year.[11]

As reported by the Faculty Scholarly Productivity Index released by the Academic Analytics organization of Stony Brook, New York, SDSU is the number one small research university in the United States for four academic years in a row.[12][13][14] SDSU sponsors the second highest number of Fulbright Scholars in the State of California, just behind UC Berkeley. Since 2005, the university has produced over 65 Fulbright student scholars.[15]

The university generates over $2.4 billion annually for the San Diego economy, while 60 percent of SDSU graduates remain in San Diego,[16] making SDSU a primary educator of the region's work force.[17] Committed to serving the diverse San Diego region, SDSU ranks among the top ten universities nationwide in terms of ethnic and racial diversity among its student body, as well as the number of bachelor's degrees conferred upon minority students.[16] San Diego State University consistently ranks in the top 500 universities in the world, and according to Forbes, is among the top 91st percentile of public colleges in the United States.[18]

San Diego State University is a member of the Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC),[19] the American Association of State Colleges and Universities, the National Association of State Universities and Land-Grant Colleges, and the Southwest Border Security Consortium.

History

Established on March 13, 1897, San Diego State University first began as the San Diego Normal School, meant to educate local women as elementary school teachers. It was located on a 17-acre (6.9 ha) campus on Park Boulevard in University Heights (now the headquarters of the San Diego Unified School District). It opened with seven faculty members and 91 students; the curriculum was initially limited to English, history and mathematics.[20] In 1923, the San Diego Normal School became San Diego State Teachers College, "a four-year public institution controlled by the state Board of Education."

By the 1930s the school had outgrown its original campus. In 1931 it moved to its current location on a mesa at what was then the eastern edge of San Diego. In 1935, the school expanded its offerings beyond teacher education and became San Diego State College.[21] In 1960, San Diego State College became a part of the California State Colleges system, now known as The California State University.[22] Finally in 1972, San Diego State College became California State University, San Diego, and in 1974 San Diego State University (SDSU).[23]

John F. Kennedy, then the President of the United States of America, gave the graduation commencement address at San Diego State University on June 6, 1963.[24][25] Kennedy was given an honorary doctorate degree in law at the ceremony, making SDSU the first California State College to award an honorary doctorate. In 1964, this event was registered as California Historical Landmark #798.[8]

John F. Kennedy, President of the United States of America. Commencement address to San Diego State University, June 6, 1963, San Diego, California, USA.[26]

On May 29, 1964, civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. addressed a near-capacity audience in the Open Air Theater. King discussed his vision for the future and called for the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, then being debated in the Senate.[27]

Martin Luther King Jr.. Public address to San Diego State University, May 29, 1964, San Diego, California, USA.[28]

In April 2012, the XIV Dalai Lama spoke at SDSU's Viejas Arena as part of his "Compassion Without Borders" tour.[29]

University presidents

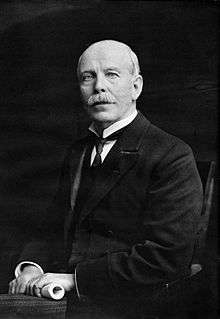

Walter R. Hepner, explaining his purpose as President[30]

SDSU has had 10 presidents, two of whom served in an acting capacity. Several structures on the campus are named in past presidents' honor, such as Hardy Tower, Hepner Hall (integrated in the university's logo), and the Malcolm A. Love Library.[31] In March 2017 President Hirshman announced his resignation for June 30, 2017; he will assume the position of president at Stevenson University in Maryland.[32] Sally Roush was the interim president until January 31, 2018.[33] On that date, the CSU Board of Trustees appointed Adela de la Torre to serve as the permanent President. She is the first woman to serve in the role on a permanent basis.[34]

- Samuel T. Black (1898–1910)

- Edward L. Hardy (1910–35)

- Walter R. Hepner (1935–52)

- Malcolm Love (1952–71)

- Donald E. Walker (1971–72, Acting)

- Brage Golding (1972–77)

- Trevor Colbourn (1977–78, Acting)

- Thomas B. Day (1978–96)

- Stephen L. Weber (1996–2011)

- Elliot Hirshman (2011–2017)

- Sally Roush (2017-2018, Acting)

- Adela de la Torre (2018–Present)

Incidents

1996 campus shooting

A shooting occurred on campus on August 15, 1996. A 36-year-old graduate engineering student, while apparently defending his thesis, shot and killed his three professors, Constantinos Lyrintzis, Cheng Liang, and D. Preston Lowrey III, at San Diego State University. The shooter, who was suffering from certain mental problems, was convicted on July 19, 1997, and was sentenced to life in prison. As a memorial, tables with a plaque with information about each victim have been placed adjacent to the College of Engineering building.

2008 student drug arrests

On May 6, 2008, the Drug Enforcement Administration announced the arrests of 96 individuals, of whom 33 were San Diego State University students, on a variety of drug charges in a year-long narcotics sting operation dubbed Operation Sudden Fall.[35] It was originally reported that 75 of the arrested were students, but the inflated number included students who had been arrested months earlier, in some cases for simple possession.[36] The bust, which was the largest in the history of San Diego County, drew a mixed reaction from the community.[37]

2014 sexual assault

In late 2014, SDSU began an "It's on Us" campaign to combat an alarming pattern of sexual violence.[38] In the fall 2014 semester, there were 14 sexual assault allegations reported on or around the college area. In early 2015, SDSU was found to have wrongfully accused a male foreign exchange student of sexual assault during the fall 2014 semester and allegedly failing to afford him due-process. The student's name was released in a campus-wide email immediately upon his arrest and he was quickly expelled from the university. The female student who made the accusation later admitted to not being truthful about the alleged incident. The male student later sued the university.[39]

Degrees

The university awards 190[40] bachelor's degrees, 91 master's degrees, 25 doctoral degrees including EdD, DPT, JD, AuD, DNP, and PhD programs in collaboration with other universities. SDSU also offers 26 different teaching credentials.[41] The university offers more doctoral degrees than any other campus in the entire California State University, while also enrolling the largest student body of doctoral students in the system.[42] In 2015, SDSU enrolled the most doctoral students in its entire history.[43]

Main Campus

Several buildings are listed on the National Register of Historic Places:[44]

- Scripps Cottage was finished in September 1931, funded with a donation of $6,000 from Ellen Browning Scripps matched with $5,000 from the state. It was the headquarters for the Associated Women Students and was used for meetings, women's activities, and served as a lounge.[45] On September 3, 1968, the building was moved to make room for the new school. It was used mainly as a conference and meeting building, and in 1993, began serving as a center for international students.[46] With the first phase of the restoration complete, Scripps Cottage is again available for meetings, celebrations and other functions. In fiscal 2016, more than 170 events were held at the site, bringing in a total of 12,000 people.[47]

- Aztec Bowl, costing $500,000, the stadium was dedicated on October 3, 1936, before 7,500 people, after being completed earlier that year. The stadium was initially supposed to be expanded to 45,000 seats, but instead was only expanded once with 5,000 seats in 1948. Aztec Bowl has been erroneously described as the only state college stadium in California at the time of its construction,[48] but at the time San Jose State University's Spartan Stadium was already three years old.[49]

- CalCoast Credit Union Open Air Theatre[50] (formerly The Greek Bowl and the Open Air Theatre) contained 4,280 seats and was financed by the Works Progress Administration and the state for $200,000. It was dedicated on May 3, 1941.[51][52]

- On January 19, 1976, the Montezuma Mesa building was renamed to Walter R. Hepner Hall, and on May 1, 1977, the Humanities building was named after John Adams, a professor, administrator, and archivist. The Humanities-Social Sciences building was renamed in 1986 after geographer Alvena Storm and historian Abraham P. Nasatir.[53]

- In the 1980s the Open Air Theatre added support facilities. Peterson Gym was finished in 1961, making the original gym the Women’s Gym until it was remodeled and reopened in 1990 as the Physical Education building. In 1990, 14,000 sq ft (1,300 m2) were added to Storm and Nasatir Halls. In 1986, a large student apartment complex was added along with an 11-story $13,000,000 residence hall (west side of campus).[54]

- Hardy Memorial Tower, in the Mission Revival style, resembles a Spanish bell tower and is one of the most recognizable buildings on campus. It houses the campanile chimes but also originally concealed a 5000-gallon water tank for the campus plumbing system. The building housed the university's first library, which featured murals painted by the Works Progress Administration.[55]

- The WPA Mission Revival Communication building, Exercise and Nutritional Sciences, Faculty-Staff Club, Life Science building and Annex, Little Theatre, Physical Plant Boiler Shop, and the Physical Science building are also listed on the National Register.[44]

Other buildings on campus include:

- The campus library, now known as the Malcolm A. Love Library, acquired its 100,000th book on May 21, 1944. By the end of World War II it was adding about 8,000 books a year.[56] In 1959, a 40,000 sq ft (3,700 m2). addition to the library was finished, but it was already deemed too small.[57] In 1952, the library had 125,000 books, and state regulations required that old books be eliminated before new ones could be added. By 1965, there were more than 300,000 books housed in a library that could hold 230,000. This was ranked highest in state colleges in terms of library size. In the 1960s, construction of a new library began, which required the relocation of Scripps Cottage. The $8,000,000 building was designed with 300,000 sq ft (28,000 m2). of space to accommodate one million books.[58] In February 1971, the library opened, housing 700,000 books, and was named after President Malcolm A. Love for his popularity on campus and his role in bringing State to university status.[59] Governor Ronald Reagan said the library would ". . . serve as a lasting memorial to the man who led the college through its growing pains . . . to one of the finest state colleges in California".[60] The building was five stories high and was the largest building on campus. A four-story sculpture entitled "Hanging Discus" by sculptor George Baker was specifically designed for the library and added to an interior staircase in November 1973.[61]

- The Conrad Prebys Aztec Student Union Student Union (formerly Aztec Center) secured financing in 2010 and was completed in March 2014, replacing and approximately doubling[62] the size of the Student Union. The facility is the first student union in the United States to qualify for LEED Platinum distinction.[63]

- The $11 million Parma Payne Goodall Alumni Center opened in October 2009 and is home to the SDSU Alumni Association and the Campanile Foundation.[64]

- In 2014, SDSU opened the newly renovated social sciences complex, Storm and Nasatir Halls. Originally built in 1957, the 137,700 square foot complex received a complete makeover to house eight academic departments from the College of Arts & Letters, newly upgraded classrooms, faculty offices, research facilities, two large lecture halls, and a food service facility. Total cost for the construction neared $74 million, began in 2012, and was completed in 2014. Included in the opening were two new named facilities: Charles Hostler Hall (a 435-seat lecture auditorium) and the J. Keith Behner and Catherine M. Stiefel Auditorium (a 252-seat lecture hall).[65]

Storm Hall was named in honor of geography department professor Alvena Storm, who served as department chair, and on the faculty for over 40 years since 1926. Nasatir Hall was named for Abraham P. Nasatir, a professor emeritus of history who taught at SDSU for 46 years (1928–74) and was later internationally recognized for his research on California history, receiving four Fulbright Fellowships.[65]

Residence halls

In 1937, Quetzal Hall, the first dormitory, opened for 40 women students and was located off campus.[51] In 1952, 50 college males conducted a panty raid at Quetzal Hall, causing $1,000 in damages. Police arrested 13 of the students and the young women later retaliated by attacking the Pi Kappa Alpha fraternity house.[66] In 1968, the coed dorm Zura Hall was built, and more rooms were added later.[67] Chapultepec Hall held 580 students when first built.[68]

Today, the university owns and operates housing for over 4,100 students in residence halls and student apartments, fraternity row, and language and honors housing. Approximately 63 percent of first-time freshman live in on-campus housing, while about 14 percent of the overall student body resides in on campus housing.[69] SDSU offers themed living communities in the freshman and upperclassman housing, such as "pathways for transfers", "gender-neutral housing", and "explore San Diego".

Off-campus facilities

Mount Laguna Observatory

Since 1968, SDSU's Astronomy Department has owned the Mount Laguna Observatory located in the Cleveland National Forest.[70]

Biological field stations

- Operated by the SDSU College of Sciences:[71]

- Santa Margarita Ecological Reserve

- Sky Oaks Field Station

- Fortuna Mountain Research Reserve

- Tijuana River National Estuarine Research Reserve

Coastal and Marine Institute Laboratory (CMIL)

The Coastal and Marine Institute Laboratory (CMIL), formerly known as the Coastal Waters Laboratory, is an academic laboratory operated by the SDSU College of Sciences. It is located on a coastal site on the grounds of the old San Diego Naval Training Center (now part of Liberty Station).

Branch campuses

Imperial Valley Campus

SDSU operates a branch campus, the Imperial Valley Campus (IVC) located in Calexico, California, with an additional campus in Brawley, California. IVC includes a research park and related facilities. The campus originally served only upper division, teacher certification, and graduate students but now serves a selective cohort of freshmen and sophomores pursuing degrees in criminal justice, liberal studies, or psychology.[72]

SDSU–Georgia campus

SDSU-Georgia is a branch campus located in Tbilisi, Georgia, in the former Soviet Republic of Georgia.[73] SDSU-Georgia is run in conjunction with three Georgian universities: Georgian Technical University (GTU), Ilia State University (ISU), and Tbilisi State University (TSU).[74] The SDSU-Georgia branch campus is offering courses leading to science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) bachelor’s degrees.[74]

Former branch campus locations

SDSU formerly operated a campus in North County (San Diego area), which was later converted into the larger California State University San Marcos. In the South Bay, SDSU operated a campus in National City, California. This campus shared facilities with Southwestern College. The South Bay Campus is now closed indefinitely.

Academics

Admissions

| 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Applicants | 60,554 | 60,545 | 58,898 | 56,759 | 54,320 |

| Admits | 21,311 | 20,858 | 20,204 | 19,524 | 20,183 |

| % Admitted | 35.2 | 34.5 | 34.3 | 34.4 | 37.2 |

| Enrolled | 5,301 | 5,011 | 5,142 | 4,978 | 4,671 |

| Avg GPA | 3.71 | 3.68 | 3.69 | 3.69 | 3.61 |

| ACT | 25.4 | 25.2 | 25.0 | 24.5 | 24.1 |

| SAT* | 1195 | 1117 | 1118 | 1115 | 1106 |

| *(out of 1600) |

| SDSU Quick Facts (2018)[76] | |

|---|---|

| Admitted High School GPA | 3.93 |

| Admitted SAT, ACT | 1264, 27 |

| Study Abroad Programs | nearly 400 |

| Number of Student Organizations | 350+ |

| Number of Greek organizations | 50+ |

| Academic Offerings | nearly 160 undergraduate majors, minors & preprofessional programs

nearly 100 graduate degrees & credentials (PhD, AuD, EdD, EdS, DNP, DPT) |

| Undergraduate Student-Faculty Ratio | 20:1 |

San Diego State University is consistently one of the most applied-to universities in the United States, receiving over 60,500 undergraduate applications (including transfer and first time freshman) for the Fall 2018 semester and accepting nearly 21,300 for an admission rate of 35.1 percent across the university,[77] the third-lowest admission rate in the 23-campus California State University system.[78]

For Fall 2018, SDSU received 23,051 applications for transfer admission and accepted 5,274 (an admission rate of 22.9 percent).[77]

Fall 2018 incoming freshman had an average high school GPA of 3.93, average ACT score of 27.0, and average SAT score of 1,264 (out of 1,600; the writing section is not considered).[79]

Enrollment

| Undergraduate | |

|---|---|

| African American | 3.7% |

| Asian American | 14.0% |

| White American | 35.6% |

| Hispanic American | 29.5% |

| Native American | 0.3% |

| International | 5.7% |

| Multiple Ethnicities | 6.5% |

| Other/Not Stated | 4.8% |

The university reached its peak enrollment in 1987 with a student body of 35,945 FTES (Full-Time Equivalent Students), which made it at the time the largest university in California and the 10th largest university in the United States.[81] Due to the overwhelming number of students and lack of facilities and majors, The California State University Board of Trustees voted to cap enrollment for SDSU at 33,000. However, in 1993 enrollment dropped to 26,800 (the lowest since 1973) due to a financial crisis.[81] Nonetheless, enrollment has fluctuated through the years and rose back to nearly 35,000 (exceeding the cap) in 2008. For the fall 2016 semester, the university had a total enrollment of 33,778 students – approximately 29,046 undergraduate and 4,732 postgraduate[82] – making it one of the largest research universities in the state of California. In fall 2013, SDSU had the most doctoral students enrolled in its history at 534 students,[42] also the highest amount of doctorate-seeking students enrolled across the 23-campus CSU system.[42]

Rankings and distinctions

| University rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| ARWU[83] | 120-137 |

| Forbes[84] | 216 |

| U.S. News & World Report[85] | 127 |

| Washington Monthly[86] | 119 |

| Global | |

| ARWU[87] | 401–500 |

| QS[88] | 701+ |

| Times[89] | 301-350 |

| U.S. News & World Report[90] | 448 |

|

USNWR graduate school rankings[91] | |

|---|---|

| Education | 54 |

| Engineering | 140 |

| Nursing: Master's | 78 |

|

USNWR departmental rankings[91] | |

|---|---|

| Audiology | 30 |

| Clinical Psychology | 25 |

| Fine Arts | 59 |

| Health Care Management | 47 |

| Mathematics | 144 |

| Nursing–Midwifery | 28 |

| Physical Therapy | 79 |

| Public Affairs | 77 |

| Public Health | 39 |

| Rehabilitation Counseling | 10 |

| Social Work | 59 |

| Speech–Language Pathology | 24 |

| Statistics | 61 |

| Forbes Best Business Schools[92] | 64 |

|---|---|

| CMUP Research Universities[93] | 154 |

| USNWR National University[94] | 146 |

| USNWR Business[94] | 87 |

| USNWR Part-Time MBA[94] | 109 |

| USNWR Education[94] | 69 |

| USNWR Engineering[94] | 140 |

| USNWR Public Affairs[94] | 73 |

| USNWR Social Work[94] | 60 |

| USNWR Undergraduate Business[95] | 73 |

From 2006 to 2010, SDSU was ranked the No. 1 most productive research university among schools with 14 or fewer PhD programs based on the Faculty Scholarly Productivity Index. The school has since exceeded the "small research" limit with 17 PhD programs, in addition to six professional doctorates. SDSU has been designated a "Research University" with high research activity by the Carnegie Foundation. Since 2000, SDSU faculty and staff have attracted more than $1.5 billion in grants and contracts for research and program administration.[96]

SDSU is the highest enrolled university in the San Diego metropolitan area. One in seven adults in San Diego who holds a college degree attended SDSU. In 2013, SDSU was lauded for its comprehensive endowment campaign efforts, which raised over $400 million from 2007 to 2013. The Council for Advancement and Support of Education recognized SDSU for its overall performance in fundraising efforts.[97]

San Diego State was ranked the 28th top college in the United States by Payscale and CollegeNet's Social Mobility Index college rankings.[98]

Money Magazine ranked San Diego State 116th in the country out of over 1500 schools it evaluated for its 2015 Best Colleges ranking.[99]

Academic Ranking of World Universities ranked San Diego State as one of the top 200 world universities for Economics/Business (between 151-200).[100]

The Daily Beast ranked San Diego State 75th in the country out of the nearly 2,000 schools it evaluated for its 2013 Best Colleges ranking.[101]

In Graduate School Rankings, QS Global 200 Business Schools Report ranks SDSU's business college the 80th best in all of North America.[102][103] Its MBA program is ranked by QS as between the 151st and 200th best in the world.[104]

The Center For World University Rankings ranks San Diego State University as #376 globally and #126 nationally as of 2017, a slightly higher global rank than either ARWU or USNWR, but slightly lower than Times. The CWUR rankings place emphasis on alumni employment and quality of teaching, rather than being purely research-based like ARWU's.[105]

SDSU is also a top producer of U.S. Fulbright Scholars, the U.S. government’s flagship international educational exchange program. SDSU has had more than 40 students receive Fulbright Scholarships since 2005.[106] The university ranks No. 30 as the nation's best universities for veterans, according to Military Times Edge.[107] SDSU ranks among the top universities for economic and campus ethnic diversity according to U.S. News & World Report's "America's Best Colleges 2012".[106] Nearly 45 percent of all SDSU graduates are the first in their family to receive a college degree.[108]

Internationally, SDSU offers 335 international education programs in 52 countries. Thirty-four SDSU programs now require international experience for graduation. SDSU ranks first in California among universities of its type in California and third among all universities in California for students studying abroad as part of their college experience. SDSU also ranks 22nd among universities nationwide for the number of students studying abroad (Institute of International Education). Since 2000, nearly 12,000 students have studied abroad: a 900 percent increase in that time. SDSU’s undergraduate international business program ranks eleventh in the nation, according to U.S. News & World Report’s "America’s Best Colleges 2012". SDSU is ranked fifth in Sports Management; 23rd in the MBA/MA in Latin American Studies; and 46th in the MBA/Juris Doctor program by Eduniversal for each programs’ international outreach and reputation in 2011. SDSU and Universidad Autónoma de Baja California in Mexico offered the first transnational dual degree between the United States and Mexico, in 1994, through the MEXUS/International Business program. SDSU's international business program also runs transnational dual degree programs with Brazil, Canada, Chile, and Mexico. SDSU’s Language Acquisition Resource Center is one of nine sites selected by the U.S. Department of Education to serve as a National Language Resource Center.[106]

SDSU ranks second among universities of its type nationwide and first in California for students studying abroad as part of their college experience.[109]

SDSU is home to the first-ever MBA program in Global Entrepreneurship.[110] As part of the program, students study at four universities worldwide, including the United States, China, the Middle East, and India.[111] Corporate partners include Qualcomm, Invitrogen, Intel, Microsoft, and KPMG.[111] In 1970, SDSU founded the first women's studies program in the country.

Modern Healthcare ranked SDSU second for graduate schools for physician executives in relation to their Master in Public Health program.[112] SDSU is ranked No. 9 in Fortune Small Business's "America's Best Colleges For Entrepreneurs".[113] SDSU ranks 15th best in the nation for the top colleges for engineering majors, and sixth best in California.[114]

The U.S. News & World Report Best Colleges for 2019 National Universities rankings awarded SDSU a spot in the top 150 national universities (#127) in the United States, classifying it as a “Top Tier” university, with particular regards to its business program.[115] U.S. News & World Report classifies San Diego State University as a "National University", whereas it classifies the other 22 universities in The California State University system as "Regional Universities".[94]

U.S. News & World Report rankings:[94] USNWR in its 2018 rankings placed SDSU 60th among Top Public Schools and 105th for High School Counselor Rankings among all universities in the nation. SDSU's College of Business Administration is ranked 87th. Additionally, its Part-Time MBA program ranks 109th. SDSU's College of Education is ranked the 71st, and its College of Engineering ranks 140th. SDSU's Audiology and its Speech and Language Pathology programs rank 27th and 25th best. Its Chemistry program ranks 131st. SDSU is home to the 26th best Clinical Psychology and 52nd best Psychology programs. Its Fine Arts program ranks 72nd. Its Healthcare Management programs ranks 48th. Its Public Affairs and Public Health programs rank 73rd and 39th. Its Rehab Counseling ranks 10th best. Furthermore, SDSU's Social Work program ranks 60th best.

In 2016, San Diego State University’s Conrad Prebys Aztec Student Union has achieved LEED Double Platinum status, joining an elite group of energy-efficient buildings. The recognition is shared by fewer than two dozen facilities around the world.[116]

Organization and administration

Schools and colleges

- College of Arts & Letters

- Fowler College of Business

- College of Education

- College of Engineering

- College of Health & Human Services (including the Graduate School of Public Health)

- College of Sciences

- College of Professional Studies & Fine Arts

- College of Extended Studies (and American Language Institute)

- Weber Honors College[117]

SDSU has two named schools established in the university by permanent endowments:

- L. Robert Payne School of Hospitality and Tourism Management[118]

- Charles W. Lamden School of Accountancy[119]

Additionally, SDSU has 11 focused schools:

- School of Communication

- School of Public Affairs

- School of Music and Dance

- School of Art and Design

- School of Exercise and Nutritional Science

- School of Social Work

- Graduate School of Public Health

- School of Journalism and Media Studies

- School of Nursing

- School of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences

- School of Theatre, Television, and Film

Endowment

The financial endowment of SDSU is valued at $220 million as of June 30, 2016.[120] The primary philanthropic arm of San Diego State University is The Campanile Foundation, controlled by the University Advancement division of the university. The San Diego State University Research Foundation, an auxiliary corporation owned and controlled by the university, is the manager and administrator of all philanthropic funds and external funding for the university and its affiliated and auxiliary foundations and corporations.

As of June 30, 2013, permanent assets of the SDSU Campanile Foundation totaled $229 million.[121]

For the 2004–2005 academic year, SDSU received over $157 million USD in external funding from grants and contracts, as well as an additional $57 million USD in donations and charitable giving.[122] For 2005–2006, SDSU received $152 million USD in grants and contracts to support research. This is followed by $47.7 million USD in donations, gifts and other charitable giving.[123]

An auxiliary to The Campanile Foundation is the Aztec Athletic Association, which primarily raises funds for the student athletes in the San Diego State University athletics programs (see discussion of Athletics below and at SDSU Aztecs).

Extracurriculars

Media, newspapers, and magazines

Students began publishing The White and Gold in 1902, which was a literary magazine and newspaper.[124] In 1913, a new newspaper was established entitled Normal News Weekly.[125] The school newspaper Paper Lantern (Normal News Weekly was renamed after the addition of the junior college) became The Aztec in September 1925.[126] It was later expanded to its current name, The Daily Aztec in fall 1959. The school's annual yearbook was named Del Sudoeste (Spanish for "of the southwest") in the early 1920s. The Koala, a comedy newspaper that is widely known around the San Diego State area, is also distributed monthly on campus but is not directly connected to the school at the moment.[126]

- SDSU media and publications

- San Diego State University Press

- The oldest university press in the California State University system with noted specializations in Border Studies, Critical Theory, Latin American Studies, and Cultural Studies.

- Hyperbole Books

- Hyperbole Books

- KCR (SDSU) College Radio

- Student-run broadcast radio station for the SDSU community

- "The Sound of State"

- KPBS Public Broadcasting TV/FM

- Television, digital television, and FM radio for the San Diego community

- An affiliate of the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) network

- "A Broadcasting Service of San Diego State University"

- 360 Magazine

- The quarterly SDSU alumni and San Diego community magazine

- Official SDSU campus newspapers

- SDSU NewsCenter

- News and information for the SDSU community

- The Daily Aztec, the largest daily collegiate newspaper in California, publishing daily since 1960.

- The Koala, the Satirical and Innovative collegiate newspaper in San Diego State

Clubs

Initial clubs that were first started on campus including the Debating Club, the Associated Student Body, YWCA, and in 1906, An Alumni Association.[124] The oldest club on campus was The Rowing Association.[127]

Formula SAE

Aztec Racing is SDSU's Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) student chapter. Every year, SDSU engineering students design and construct an open wheel, open cockpit race car to Formula SAE (formerly Formula Society of Automotive Engineers) specifications. Aztec Racing then competes against other universities' Formula SAE teams in an annual competition event, where the cars are raced against each other and judged on design. Attendance at Formula SAE competition is international, with several hundreds of schools competing each year. Students from other majors participate as well, frequently in the areas of management, promotion and other aspects of the project.

Athletics

| Men's Sports | Women's Sports |

|---|---|

| Baseball | Basketball |

| Basketball | Cross Country |

| Football | Golf |

| Golf | Lacrosse |

| Soccer | Rowing |

| Tennis | Soccer |

| Softball | |

| Swimming & Diving | |

| Tennis | |

| Track & Field† | |

| Volleyball | |

| Water Polo | |

| † – Track and field includes both indoor and outdoor. | |

SDSU's intercollegiate athletic teams are referred to as the "Aztecs". The university currently sponsors six men's and thirteen women's sports programs at the varsity level.

The first major sport on campus was rowing, but it initially had no coaches or tournaments.[128] Other sports that developed early in the campus's history were tennis, basketball, golf, croquet, and baseball.[128] Early on, the school's football program had such a limited selection of players that faculty had to be used to fill the roster.[128] When the college merged with the junior college in 1921, the college became a member of the Junior College Conference. After the school won most of the conference titles in a variety of sports, the league requested that college leave out of fairness to the smaller schools. For its football program, the team outscored its opponents 249 to 52 in ten games, resulting in the first sales of season tickets in 1923.[129] From 1925 to 1926, the college played as an independent. It then joined the Southern California Conference in 1926, where it did not win a football conference championship until 1936. However, in other sports including tennis and basketball, it excelled.[129] The college remained with the conference until 1939, when it joined the California Collegiate Athletic Association.[130]

The basketball team reached and won multiple championship games during the 1930–1940s, including a conference title in 1931, 1934, 1937, and 1939. It reached the national championship in 1939 and 1940, losing in the final rounds. However, in 1941 the college returned and won the college's first national title.[130] In track, the team won conference titles in 1935, 1936, 1937, 1938, and 1939.[130] The football team won conference titles in 1936 and 1937, and the baseball team won three conference titles and placed second three times between 1935 and 1941.[130]

In 1955, the Aztec Club was established and raised $20,000 a year by 1957. The club worked in increasing athletic scholarships, hiring better coaches, and developing the college’s intercollegiate athletic programs. In 1956, students approved through a vote of allowing a mandatory student activity fee, with a portion going to athletics. By the end of the decade the budget had doubled to $40,000. The campus’s most successful sports program during the 1950s was cross-country, when the team won eight straight conference titles and AAU regional titles and placed high in national competitions. Basketball teams ranged from last in the conference to multiple conference, regional, and national appearances. The football program had its first undefeated team in 1951, but in the last part of the decade earned the worst records in the school’s football program under the direction of head coach Paul Governali.[131]

Under Governali, the campus’s football program suffered due to Governali’s policy of not recruiting players. To improve the program, Love hired in 1961 Don Coryell, who led the program win three consecutive championships (1966–68), and 104 wins, 19 losses, and 2 ties by the time he left SDSU. Coryell was assisted by John Madden, Joe Gibbs, and Rod Dowhower, among others. In Coryell’s first year, attendance at home games averaged 8,000 people, but by 1966 it had doubled to 16,000. This later jumped to 26,000–41,000 per game with the addition of the new San Diego Stadium. At some games, attendance was larger than at San Diego Chargers games. There were several undefeated seasons and many players broke records for most catches, touchdowns, and passing yards. In 1969, San Diego State College moved into NCAA Division I, leaving the California Collegiate Athletic Association. In 1972, Coyrell left to pursue coaching in the NFL.[132]

Basketball also did well, with the 1967–68 team being ranked the number one college-level team in the nation, although it did not win a national title. The Aztecs also won the 1960 CCAA baseball title and multiple national championships throughout the 1960s in track, cross country, and swimming.[132]

By 1970–71, the campus had 14 NCAA sports. The 1973 men’s volleyball team won the NCAA national championship which was the first NCAA national title since moving to Division I status.[133]

SDSU competes in NCAA Division I FBS. Its primary conference is the Mountain West Conference; its women's rowing team competes in the American Athletic Conference, its women's water polo team participates in the Golden Coast Conference, and its men's soccer team is a single-sport member of the Pac-12 Conference (Pac-12). The ice hockey team competes in the ACHA with other western region club teams (www.sdsuhockey.com). The crew team's championship regatta is in the WIRA (Western International Rowing Association). The university colors are scarlet (red) and black, SDSU's athletic teams are called the "Aztecs", and its mascot is the Aztec Warrior, formerly referred to as "Monty Montezuma".

Baseball & Softball

The baseball team plays at Tony Gwynn Stadium on the SDSU campus, opened in 1997 and named after former SDSU baseball and basketball player, late head coach, and Major League Baseball Hall of Fame inductee Tony Gwynn. The playing field is officially called Charlie Smith Field, after the longtime SDSU baseball head coach Charles R. Smith.[134]

The softball team plays at the SDSU Softball Stadium, completed in 2005 adjacent to Tony Gwynn Stadium.

Basketball

The men's and women's basketball teams play at Viejas Arena, opened in 1997, on the SDSU campus. The court is officially named Steve Fisher Court, after longtime SDSU basketball head coach Steve Fisher. Both teams practice at the Jeff Jacobs JAM Center, a basketball practice facility that opened on campus in 2015.

Football

The football team plays at SDCCU Stadium (formerly known as Qualcomm Stadium).

Soccer

The men's and women's soccer teams both play on campus at the SDSU Sports Deck, a facility opened in 2000 that also hosts the women's track and field team The women compete in the Mountain West Conference while the men compete in the Pac-12 Conference.

Tennis

The men's and women's tennis teams both play at the Aztec Tennis Center, a 12-court complex opened in 2005 at the west end of the campus.

Volleyball

The women's volleyball team plays in Peterson Gym on the SDSU campus. The men's volleyball team won the NCAA National Championship in 1973 (SDSU's first and only NCAA Division I national championship to date in any sport), but the program was disbanded in 2000 due to budgetary constraints and necessity to maintain compliance with Title IX regulations.[135]

Other sports

- The on-campus aquatic sports complex (known as the Aztec Aquaplex), was opened in 2007 and includes an Olympic-size swimming pool with a moveable bulkhead, a separate recreational pool, and a hydrotherapy spa. This facility is home to the women's swimming and diving team and the women's water polo team. This facility also serves as the recreational pool for SDSU students and community members.

- In conjunction with the UCSD, the Associated Students organization of San Diego State University runs the Mission Bay Aquatic Center (MBAC) in Mission Bay, just a few miles west of the main campus. The MBAC is the home to the women's rowing team. It also provides for many outdoor activities and sports for SDSU students.

Student body and Greek life

Fraternities and sororities have been a part of the San Diego State University campus community since 1899. Today SDSU is home to many recognized Greek-letter organizations, most of which belonging to one of four university-sponsored governing councils. The Interfraternity Council (IFC) currently consists of 15 social fraternities. The College Panhellenic Association (CPA) is made up of 9 social sororities.

| Fraternities (IFC)[136] | Sororities (CPA)[137] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

SDSU's Greek system also includes several multi-cultural Greek organizations. The United Sorority & Fraternity Council (USFC) is the governing body for 18 culturally-based Greek-letter organizations (7 fraternities, 11 sororities) and the National Pan-Hellenic Council (NPHC) is the governing body of historically African American Greek-letter organizations at SDSU (2 fraternities: Kappa Alpha Psi, Omega Psi Phi; 3 sororities: Delta Sigma Theta, Sigma Gamma Rho, and Zeta Phi Beta).[138]

The first fraternity on campus was the Delta chapter of Epsilon Eta, which formed on October 25, 1921. By the end of the decade there were six other fraternities and eight sororities. The fraternities and sororities were all local and did not attain national status until after World War II.[127] In 1925, in order to encourage higher grades, the Inter-Fraternity Council and Inter-Sorority Council published the average grades of the fraternity and sorority members. On a 3.0 scale, the average GPA (grade point average) for all students was 1.49, for fraternities was 1.35, and sororities was 1.47.[127] By the mid-1930s there were eight fraternities and eleven sororities,[51] and later expanded to fifteen fraternities and twelve sororities in the 1940s.[139] The first fraternity to go national was Theta Chi and the first sorority was Alpha Xi Delta.[139]

During the 1960s and early 1970s, the Greek population had dwindled to 699, but gradually began to increase in the 1980s, reaching 2,900 in 1988. There were 20 fraternities and 13 sororities officially affiliated with the Inter Fraternity Council and Panhellenic Council as well as six independent fraternities/sororities. This made it one of the largest fraternity and sorority systems in the western U.S.[140] On April 6, 1978, Gamma Phi Beta sorority hired a plane to drop marshmallows on fraternity houses during Derby Week, but the plane crashed near Peterson Gym, injuring four students aboard.[141] After, a 1983 USA Today article reported that SDSU Greeks' GPAs were below the campus average, SDSU tightened restrictions and supervision, and by 1989 their grades had increased to slightly above the university average.[141] Between 1989 and 1991, several riots among the fraternities occurred, including one numbering 3,500 people and another requiring 34 police officers to end it.[142] The 2008 drug bust resulted in the suspension of several fraternities as well as the arrests of multiple fraternity members.[143] Currently there are over 50 social fraternities and sororities, including general, professional, and culturally based organizations represented by five governing councils.

In 2002, the university's SDSU Foundation opened Fraternity Row, a 1.4 acre complex build adjacent to Viejas Arena. The complex consists of eight free-standing two story chapter houses, each with a private courtyard, and a total of 61 two and three bedroom apartment units in a contiguous four story structure.[144] The Foundation had planned to also construct "Sorority Row", a similar project designed with five free-standing chapter houses, following the completion of the Piedra Del Sol apartment complex and Fraternity Row. The project was abandoned in 2006 however, after the Foundation declared the project financially infeasible, citing escalating construction-material costs.[145]

On April 27, 1974, The Phi Beta Kappa Society established an SDSU chapter. It was the first in the CSU system as well as the San Diego area.[81]

Other multidisciplinary national honor societies include Phi Kappa Phi, Mortar Board, and Phi Eta Sigma.

LGBT-Friendly campus

San Diego State University was recognized in 2016 among the best universities in the nation for supporting LGBT students. The Campus Pride Index recently ranked SDSU on its 2016 “Best of the Best” Top 30 list of LGBTQ-friendly colleges and universities. SDSU has been included in this ranking for the past seven years along with institutions like Princeton University and Cornell University.[146]

SDSU was recognized in 2014 as one of 20 of the most Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender-friendly campuses in all of the U.S.[147][148] The university attains this recognition through its welcome week LGBT reception, Safe Zone ally training, Big Gay BBQs, participating in Aids Walk San Diego and Pride San Diego, hosting an LGBT college fair, and holding a Lavender Graduation ceremony and several lecture series. The university is one of the few campuses in California that is home to the gay social fraternity, Delta Lambda Phi. Additionally, SDSU was the first university in California to offer a major in LGBT studies, while also offering a minor and graduate degree in the discipline.[149] In 2014, SDSU opened a first-ever Pride Center at the former Student Organization Annex, with the mission to provide resources and help meet the needs and challenges of LGBT students.[150]

Traditions

- The San Diego State Marching Aztecs and Pep and Varsity Bands are often seen at many sporting events including Football, Basketball and even Volleyball.

- The San Diego State University (SDSU) campus is known as "Montezuma Mesa", as the university is situated on a mesa overlooking Mission Valley and is located at the intersection of Montezuma Road and College Avenue.

- Undie Run through campus that takes place during finals week each semester.

S mountain

On February 27, 1931, President Hardy permitted 500 students to paint rocks to form a 400-foot (120 m) white S on Cowles Mountain. The idea of "S Mountain" was created by the Council of Twelve and initially supported by Hardy. The giant S was lit at night for the opening football game of a season (performed by the freshman to build school spirit) along with pep rallies, and was repainted throughout its history.[45][151] At the time, it was the largest collegiate symbol in the world.[152] During World War II, the S was camouflaged to prevent it becoming a reference point for enemy bombing aircraft.[153] It was returned to its normal state in April 1944.[154] In the 1970s students stopped painting it and brush obstructed the symbol. After a 1988 brush fire it was exposed, and students repainted it. In fall 1997, a group of 100 volunteers climbed Cowles Mountain after dusk to commemorate the one hundredth anniversary of the school by using flashlights to once again outline the S on the side of the mountain. In 1990, a high school prank defaced the S to read as "91" in honor of their graduating class.[155]

School colors and mascot

The initial colors of the school were white and gold. When the junior college was added to the campus in 1921, its colors of blue and gold were merged, resulting in a blue, gold, and white color scheme. New colors were later chosen as gold and purple, until being replaced by scarlet and black on January 28, 1928.[156]

The school's prior nicknames for its mascot included "Normalites", "Professors", and "Wampus Cats". However, after a 1924 committee met to address the issue, the name "Aztecs" was decided on.[126] In 2003, the Aztec Warrior was approved by a student and alumni vote to become the official university mascot after the school's prior mascot, Monty Montezuma, was discontinued.[157] In 2018, SDSU discontinued use of the Aztec Warrior as a mascot.[158]

Mascot Controversy

Like other mascots referencing historical tribes and cultures, the Aztec mascot has periodically been the topic of question. It was not cited as "hostile and abusive" by the NCAA in 2005 due to a decision that the Aztecs were not a Native American tribe with any living descendants.[159] However, the Aztec Warrior has drawn criticism. A SDSU professor of American Indian Studies states that among other problems the mascot teaches the mistaken idea that Aztecs were a local tribe rather than living in Mexico 1,000 miles away.[160] The SDSU Native American Student Alliance (NASA) supports removal of the mascot, calling its continued use "institutional racism" in an official statement to the Committee on Diversity, Equity and Outreach.[161][162] Although that resolution was rejected by the SDSU Associated Students, the University Senate, which represents the administration, faculty, staff and students, had voted to phase out the human depiction of the Aztec Warrior.[163] In 2018, after the recommendation of a task force of students, faculty, and alumni who were appointed to study the issue, President Sally Roush made the decision to discontinue using the Aztec Warrior as a mascot, while retaining it as a "Spirit Leader."[164][158]

Popular culture

- Film and television

- The two main characters from the 2004 Academy Award-winning comedy/drama film Sideways were roommates during their college days at SDSU.

- The SDSU campus is the setting of Hearst College, the fictional university in The CW television network show Veronica Mars.

- The exterior shots of Rancho Carne High School in the movie Bring it On were mainly filmed at San Diego State University

- Portions of The Real World: San Diego were filmed around the SDSU campus

Notable alumni and faculty

San Diego State University has over 260,000 alumni worldwide. The university is one of the top producers of U.S. Student Fulbright Scholars in the nation.[165]

Gregory Peck, Actor

Darren Kavinoky, Lawyer and TV Personality

Ellen Ochoa, Director of the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center

B.S. Physics 1980

Julie Kavner, Actress and Voice of Marge Simpson

B.A. Drama 1973

Marion Ross, Actress

B.A. Drama 1950

Ralph Rubio, CEO of Rubio's Fresh Mexican Grill

B.A. Liberal Studies 1978[166]

Roger T. Benitez, U.S. Federal Judge

Jerry Sanders, former Mayor of San Diego and former SDPD Chief of Police

Kevin Faulconer, current Mayor of San Diego

B.A. Political Science 1990Merrill McPeak, Chief of Staff, U.S. Air Force

B.A. Economics 1957

Courtney Friel, Los Angeles News Anchor and Fox News Anchor

B.A. Political Science 2002

Kathleen Kennedy, Movie Producer (Jurassic Park, E.T.)

B.A. Telecommunications and Film 1975

Tony Gwynn, MLB Hall of Fame

Marshall Faulk, NFL Hall of Fame .jpg)

Tony Gwynn Jr., former MLB Player

Stephen Strasburg, MLB pitcher

Kawhi Leonard, NBA player

Xander Schauffele, PGA Tour golfer  Vic Fuentes, Musician (lead singer, songwriter and guitarist of Pierce the Veil)

Vic Fuentes, Musician (lead singer, songwriter and guitarist of Pierce the Veil)

References

- ↑ "TCF", SpringerReference, Springer-Verlag, retrieved 2018-09-21

- ↑ "2017/2018 Budget" (PDF). San Diego State University. September 30, 2013. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 28, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- 1 2 "Profile of CSU Employees" (PDF). California State University. Fall 2013. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 28, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Table 1 Total Enrollment by Sex and Student Level, Fall 2017". Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ↑ "San Diego State University". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- ↑ San Diego State University Brand Manual (PDF). 2012-05-23. Retrieved 2016-03-28.

- ↑ National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 "San Diego State University". Office of Historic Preservation, California State Parks. Retrieved 2012-10-13.

- ↑ "Home - SDSU". sdsu.edu.

- ↑ "Carnegie Classifications | Lookup & Listings". Center for Postsecondary Research. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ↑ http://advancement.sdsu.edu/AandD/index.html

- ↑ "Study Ranks California's Most Productive Universities (May 31, 2007)". Prweb.com. Retrieved January 1, 2013.

- ↑ "SDSU named most productive small research school". North County Times. June 1, 2007. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- ↑ "SDSU Receives Top Research Distinction for Second Straight Year". SDSUniverse.com (Nov. 26, 2007)

- ↑ "Fulbright Program Awards Six SDSU Students". sdsu.edu.

- 1 2 "SDSU Significant Rankings and Distinctions". Advancement.sdsu.edu. Retrieved January 1, 2013.

- ↑ "Top Ten Reasons to Support San Diego State University" (PDF). Newsccenter.sdsu.edu. Retrieved 2015-05-16.

- ↑ Forbes SDSU. Ranked #69 among public colleges and universities in 2018; according to the National Center for Education Statistics, there are 737 public colleges and universities in the U.S., exclusive of two-year colleges.

- ↑ "San Diego State University". www.wascsenior.org. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ↑ "In the beginning". San Diego State University. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ↑ "1931 Relocation". San Diego State University. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ↑ "University History and Mission | SDSU". newscenter.sdsu.edu. Retrieved 2017-08-15.

- ↑ Chancellor, California State University Office of the. "Celebrating 50 Years - Timeline & Milestones". www.calstate.edu. Retrieved 2017-08-15.

- ↑ Forty Years Later, the Magic of JFK Lingers on the Mesa Archived 2007-07-06 at the Wayback Machine., Coleen L. Geraghty, SDSUniverse (May 12, 2003)

- ↑ "SDSU Library, Aztec Bowl: History of San Diego State University (accessed Jan. 16, 2009)". Infodome.sdsu.edu. Archived from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved January 1, 2013.

- ↑ "President John F. Kennedy's 1963 Commencement Speech at San Diego State". San Diego State University Special Collections & University Archives. Archived from the original on June 27, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ↑ "MLK on the Mesa". SDSU NewsCenter. 2012-01-17.

- ↑ "SDSU commemorates MLK speech". The Daily Aztec. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Dalai Lama Shares Compassion". Newscenter.sdsu.edu. April 20, 2012. Retrieved January 1, 2013.

- ↑ Starr, p. 93

- 1 2 "University History | SDSU". Newscenter.sdsu.edu. Retrieved 2014-08-17.

- ↑ Hirsh, Lou (March 8, 2017). "Hirshman Leaving SDSU President Post in June". San Diego Business Journal. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ↑ Xia, Rosanna (2017-05-24). "Search begins for new San Diego State president as trustees announce salary for interim leader". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2017-08-13.

- ↑ http://newscenter.sdsu.edu/sdsu_newscenter/news_story.aspx?sid=77084

- ↑ "Mug Shots from Operation Sudden Fall" (PDF). CBS News 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 30, 2008. Retrieved May 6, 2008.

- ↑ Kucher, Karen (May 8, 2008). "Officials differ on number of SDSU students snared in sting". San Diego Union Tribune. Archived from the original on June 27, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ↑ Saavedra, Sherry; Kristina Davis (May 8, 2008). "SDSU drug sting draws scorn, praise". San Diego Union Tribune. Archived from the original on June 28, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ↑ "What to do about SDSU sex-assault crisis - UTSanDiego.com". U-T San Diego.

- ↑ Gary Warth. "Suspended SDSU student sues to see evidence against him - UTSanDiego.com". U-T San Diego.

- ↑ "Achievements & Distinctions". advancement.sdsu.edu. Retrieved 2017-02-01.

- ↑ "California State University Credential Programs • 2013-2014" (PDF). Degrees.calstate.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-24. Retrieved 2015-05-16.

- 1 2 3 Monica Malhotra; Lisa Limbeek. "CSU | AS | Student Enrollment in Degree Programs Report - Fall 2012". Calstate.edu. Retrieved 2014-08-17.

- ↑ "SDSU Analytic Studies and Institutional Research" (PDF). Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- 1 2 "Historic Buildings of San Diego State University". Infodome – SDSU Historic Buildings. San Diego State University. Archived from the original on September 6, 2006. Retrieved July 30, 2009.

- 1 2 Starr, p. 78

- ↑ Starr, p. 156

- ↑ "NewsCenter | SDSU | Scripps Cottage Restored". Retrieved 2017-02-01.

- ↑ Starr, p. 94

- ↑ "SJSUSpartans.com - San Jose State University Official Athletic Site". Sjsuspartans.com. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ↑ Wood, Matthew (November 13, 2013). "SDSU's Open Air Theatre Gets Name Change". KNSD. NBCUniversal. Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Starr, p. 96

- ↑ Hall, Matthew T. (May 3, 2011). "SDSU's Open Air Theatre still stepping out at 70". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Tribune Publishing. Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- ↑ Starr, p. 191

- ↑ Starr, p. 202

- ↑ "Hardy Memorial Tower". Infodome – SDSU Historic Buildings. San Diego State University. Archived from the original on February 8, 2007. Retrieved July 30, 2009.

- ↑ Starr, p. 125

- ↑ Starr, p. 138

- ↑ Starr, p. 155-56

- ↑ Starr, p. 187

- ↑ Starr, p. 188

- ↑ Starr, p. 189

- ↑ Guerrero, Amanda (March 21, 2013). "A look at SDSU's student union throughout the years". The Daily Aztec. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ↑ Barlett, Peggy; Geoffrey W. Chase (August 16, 2013). Sustainability in Higher Education: Stories and Strategies for Transformation. MIT Press. p. 254. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ↑ Lee, Jaimy (April 14, 2008). "Tucker Sadler has designs on $11m center at SDSU". San Diego Business Journal. Retrieved October 11, 2008.

- 1 2 Natalia Elko (2014-02-21). "Storm and Nasatir Halls Grand Opening and Dedication". Newscenter.sdsu.edu. Retrieved 2014-08-17.

- ↑ Starr, p. 143

- ↑ Starr, p. 168

- ↑ Starr, p. 220

- ↑ "SDSU Analytic Studies and Institutional Research" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 April 2013. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ↑ Mount Laguna Observatory

- ↑ fs.sdsu.edu/kf/(subscription required) Archived 2011-08-09 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Archived September 8, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "San Diego State University Georgia". Georgia.sdsu.edu. 2016-01-04. Retrieved 2016-03-28.

- 1 2 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved November 3, 2015.

- ↑ "First-time Freshmen Apps, Admits, and New Enrollees". San Diego State University Analytic Studies & Institutional Research. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ "Fast Facts | Office of Admissions | SDSU". admissions.sdsu.edu. Retrieved 2018-09-21.

- 1 2 "New Student Admissions". San Diego State University Analytic Studies & Institutional Research. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ↑ "CSU NEW STUDENTS (DUPLICATED) APPLICATIONS AND ADMISSIONS BY CAMPUS AND STUDENT LEVEL, FALL 2016, ALL APPLICANTS". California State University Office of the Chancellor. December 9, 2016.

- ↑ San Diego State University. ["Fast Facts"]. Accessed October 06, 2018.

- ↑ "(no page)" (PDF). Retrieved September 27, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Starr, p. 193

- ↑ "Fast Facts | SDSU". newscenter.sdsu.edu. Retrieved 2017-02-01.

- ↑ "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2017: USA". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- ↑ "America's Top Colleges". Forbes. July 5, 2016.

- ↑ "Best Colleges 2017: National Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. September 12, 2016.

- ↑ "2016 Rankings - National Universities". Washington Monthly. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ↑ "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2017". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- ↑ "QS World University Rankings® 2018". Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. 2017. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- ↑ "World University Rankings 2016-17". THE Education Ltd. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ↑ "Best Global Universities Rankings: 2017". U.S. News & World Report LP. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

- 1 2 "San Diego State University - U.S. News Best Grad School Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "The Best Business Schools". Forbes. October 2013. Archived from the original on June 27, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ↑ "The Top American Research universities" (PDF). Mup.asu.edu\accessdate=2015-05-16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "San Diego State University | Overall Rankings | U.S. News Best Colleges Rankings |". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved 2018-09-13.

- ↑ "US News Undergrad - Business School Rankings - Library Guides at Wake Forest Univ. - Prof. Center Library". Libguides.mba.wfu.edu. 2013-04-26. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- ↑ "Achievements & Distinctions". Newscenter.sdsu.edu. Retrieved 2014-08-17.

- ↑ "2013 Winners". CASE. Retrieved 2014-08-17.

- ↑ "Social Mobility Index". Social Mobility Index. CollegeNet and PayScale. 2014. Retrieved June 5, 2015.

- ↑ "Money's Best Colleges". Money. 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ↑ "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2017: USA". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- ↑ "The Daily Beast's Guide to the Best Colleges 2013". The Daily Beast. October 16, 2013. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ↑ Archived June 26, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ QS MBA Rankings. 2018.

- ↑ QS Global MBA Rankings 2018.

- ↑ CWUR 2017 - World University Rankings.

- 1 2 3 "Achievements & Distinctions". Newscenter.sdsu.edu. Retrieved 2014-08-17.

- ↑ Sunday, August 17, 2014 (2010-10-11). "SDSU Ranks No. 30 on List of Best Universities for Vets | NewsCenter | SDSU". Newscenter.sdsu.edu. Retrieved 2014-08-17.

- ↑ "Graduation Facts | 100,000 Graduates Strong". Blogs.calstate.edu. Archived from the original on 2014-06-29. Retrieved 2014-08-17.

- ↑ "San Diego State University | The Impact of the California State University". Calstate.edu. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- ↑ Walker, Peter (December 4, 2006). "The globe-trotting MBA". CNN. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- 1 2 Di Meglio, Francesca (November 21, 2006). "San Diego State's Global Perspective". Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on June 28, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ↑ "SDSU No. 2 Grad School for Physician Execs". newscenter.sdsu.edu. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- ↑ FSB staff, FSB staff. "America's Best Colleges for Entrepreneurs". Fortune Small Business. Retrieved April 29, 2012.

- ↑ School Name. "Online Engineering Degree Programs". AffordableCollegesOnline.org. Retrieved 2014-08-17.

- ↑ https://www.usnews.com/best-colleges/rankings/national-universities?int=9ff208

- ↑ http://newscenter.sdsu.edu/sdsu_newscenter/news_story.aspx?sid=76557

- ↑ "Weber Honors College Homepage". Newscenter.sdsu.edu. Retrieved 2015-12-22.

- ↑ "L. Robert Payne School of Hospitality and Tourism Management - Contact". Htm.sdsu.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-03-28.

- ↑ Janie Chang. "Charles W. Lamden School of Accountancy : SDSU College of Business Administration". Cbaweb.sdsu.edu. Retrieved 2016-03-28.

- ↑ As of June 30, 2016. "U.S. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year (FY) 2016 Endowment Market Value and Change in Endowment Market Value from FY 2015 to FY 2016" (PDF). National Association of College and University Business Officers and Commonfund Institute. 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-04-02.

- ↑ "The Campanile Foundation Financial Report" (PDF). SDSU Campanile Foundation. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 27, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ↑ "2004–2005 Annual Report on External Funding, California State University". Calstate.edu. Retrieved January 1, 2013.

- ↑ "2005–2006 Annual Report on External Support to the CSU – San Diego State University". Calstate.edu. Retrieved January 1, 2013.

- 1 2 Starr, p. 27

- ↑ Starr, p. 39

- 1 2 3 Starr, p. 53

- 1 2 3 Starr, p. 59

- 1 2 3 Starr, p. 28

- 1 2 Starr, p. 60

- 1 2 3 4 Starr, p. 102, 105

- ↑ Starr, p. 144-45

- 1 2 Starr, p. 159-62

- ↑ Starr, p. 221

- ↑ "Tony Gwynn Stadium – San Diego State Aztecs | Stadium Journey". stadiumjourney.com. Retrieved 2018-07-04.

- ↑ Union-Tribune, San Diego. "Memories linger of Aztecs' 1973 men's title team". sandiegouniontribune.com. Retrieved 2018-07-04.

- ↑ "San Diego State IFC fraternities". San Diego State University Interfraternity Council. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ↑ "San Diego State CPA sororities". San Diego State University College Panhellenic Association. Archived from the original on 2018-05-30. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ↑ "Greek Life at San Diego State University". San Diego State University. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- 1 2 Starr, p. 127

- ↑ Starr, p. 214

- 1 2 Starr, p. 215

- ↑ Starr, p. 216

- ↑ McDonald, Jeff; Sherry Saavedra; Tanya Sierra (May 7, 2008). "Major SDSU drug probe nets 96 arrests in raids". San Diego Union Tribune. Archived from the original on June 28, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Real Estate Development Projects". Pierce Education Properties, L.P. Retrieved 2018-07-04.

- ↑ Staff. "Sorority Row plans stay stagnant". The Daily Aztec. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- ↑ http://newscenter.sdsu.edu/sdsu_newscenter/news_story.aspx?sid=76292

- ↑ "Top 50 LGBT-friendly colleges". Washingtonblade.com. 2014-08-13. Retrieved 2014-08-17.

- ↑ Flynn, Pat (July 27, 2010). "SDSU campus among 20 most LGBT-friendly". U-T San Diego. Archived from the original on June 28, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ↑ Kucher, Karen (December 13, 2013). "SDSU offers certificate in LGBT studies". U-T San Diego. Archived from the original on June 28, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ↑ Chang, Denise (October 7, 2013). "SDSU approves Pride Resource Center". The Daily Aztec. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ↑ Starr, p. 126

- ↑ Starr, p. 79

- ↑ Starr, p. 112

- ↑ Starr, p. 121

- ↑ Starr, p. 213

- ↑ Starr, p. 50

- ↑ Jenkins, Brandon; Melissa Berlant (December 15, 2003). "San Diego State U.: San Diego State U. approves university mascot". The America's Intelligence Wire. Retrieved November 10, 2008.

- 1 2 "SDSU to keep Aztec name following racially and politically charged debate". May 17, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- ↑ Schrotenboer, Brent (August 6, 2005). "NCAA puts limited ban on Indian mascots: Postseason policy doesn't hit Aztecs". San Diego Union-Tribune.

- ↑ Warth, Gary. "SDSU professor revives fight to change Aztec mascot". San Diego Union-Tribune.

- ↑ Allyson Myers (February 27, 2017). "Native American Student Alliance proposes removal of Aztec mascot". The Daily Aztec.

- ↑ "NASA 2016-2017 Mascot Statement". Retrieved February 28, 2017.

- ↑ Alexander Nguyen (November 8, 2017). "No More Aztec Warrior? SDSU University Senate Votes to Retire Mascot". Times of San Diego.

- ↑ Kirk Kenney (January 19, 2018). "SDSU president assembling task force to review Aztec mascot, moniker". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- ↑ "Top Producers of U.S. Fulbright Students by Type of Institution, 2011-12 - International - The Chronicle of Higher Education". Chronicle.com. 2011-10-23. Retrieved 2014-08-17.

- ↑ http://thedailyaztec.com/55198/daily-aztec-stories/then-and-now-famous-aztec-graduates/

Bibliography

- Starr, Raymond; Harry Polkinhorn (1995). San Diego State University: A History in Word and Image. San Diego State University Press. ISBN 1-879691-30-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to San Diego State University. |