Recognition of same-sex unions in Costa Rica

Same-sex marriage is currently not recognized in Costa Rica. However, a ruling by the Supreme Court on 8 August 2018 declared unconstitutional the sections of the Family Code that impede same-sex marriage, and gave the Legislative Assembly 18 months to reform the law accordingly, otherwise the sections of the Code would be abolished automatically. This followed a ruling issued in January 2018 by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights stating that American Convention on Human Rights signatory countries are required to allow same-sex marriage. The Government subsequently announced that it would abide by the ruling.

Civil unions

The legal recognition of same-sex unions has been debated periodically since 2007, with the debate resurfacing in May 2009 and causing significant controversy due to the strong influence of the Catholic Church in the nation.[1]

In 2008, a group opposed to same-sex unions asked the Costa Rican electoral authority, the Tribunal Supremo de Elecciones (TSE), to hold a referendum on the subject, an action opposed by most organizations supporting same-sex civil unions in the country. On October 1, 2008, the TSE authorized the group to start collecting the signatures required by law to trigger the referendum (5% of registered voters). By July 2010, the required signatures had been collected and the TSE started the process to hold the referendum on December 5, 2010. In the meantime, several organizations and individuals, including the Ombudsman Office of Costa Rica, asked the Supreme Court to consider the legality of the proposed referendum. On August 10, 2010, the Supreme Court declared such a referendum unconstitutional. The court concluded that same-sex couples constituted a disadvantaged minority group subject to discrimination, and that allowing a referendum regarding their rights would potentially enable the non-LGBT majority to limit their rights, and thus increase the discrimination. It then fell to Costa Rica's Congress to legislate for same-sex unions.[2]

On July 2, 2013, the Legislative Assembly unanimously passed a measure that could legalize same-sex civil unions as part of a larger bill amending the Law of Young People. The passing of the bill was widely acknowledged to be a mistake by legislators unaware of its implications; those voting for the bill included legislators vocally opposed to LGBT rights. The mistake, however, did not impact the legality of the bill. The bill changed article 22 of the Law of Young People to recognize: "The right to recognition without discrimination contrary to human dignity, social and economic effects of domestic partnerships that constitute publicly, notoriously unique and stable, with legal capacity for marriage for more than three years." The bill also changed the country's Family Code to allow couples living together for three years or more to be recognized as having a common-law marriage, which would grant them the benefits of legal partners such as alimony.[3] The final approved version of the bill did not define marriage as being between people of the opposite sex.[4] On July 4, 2013, President Laura Chinchilla signed the bill into law. A statement from the Minister of Communication said that it was not up to her to veto that bill and that the responsibility for interpreting it lay with legislators and judges.[5]

In July 2013, a same-sex couple filed an appeal with the Supreme Court asking for their union to be recognized under the new law. LGBT rights activists reacting to the law said it needed to survive a constitutional challenge in court.[6][7] Some constitutional lawyers stated that same-sex couples would "still lack legal capacity" to formalize their unions, despite the passage of the bill.[8]

On December 3, 2014, Vice President Ana Helena Chacón Echeverría confirmed that four same-sex union proposals would be debated starting in January 2015. President Luis Guillermo Solís said on November 27 that he supported a coexistence initiative to grant couples economic rights, but not any of the civil union proposals equivalent to marriage.[9] In mid-March 2015, two government proposals were submitted and examined. On August 12, 2015, the Government sent a partnership proposal to the Legislative Assembly extraordinary sessions, seeking to make Article 242 of the Family Code's definition of cohabitation gender-neutral.[10]

In June 2015, a Costa Rican judge granted a common-law marriage to a same-sex couple, Gerald Castro and Cristian Zamora, basing his ruling on the July 2013 legislation.[11] Conservative groups subsequently filed a suit accusing the judge of breach of duty. A criminal court cleared the judge in April 2018.[12]

In early July 2018, six deputies from the Social Christian Unity Party introduced a civil union bill to the Legislative Assembly, as the party opposes the legalization of same-sex marriage. Under the proposed bill, same-sex couples would be granted almost all of the rights of marriage.[13]

Same-sex marriage

History

On May 23, 2006, the Supreme Court ruled against same-sex couples seeking to be legally married. In a 5-2 decision, the court ruled that it was not required by the country's Constitution to recognize same-sex marriage in family law.[14]

On March 19, 2015, a bill to legalize same-sex marriage was introduced to the Legislative Assembly by Deputy Ligia Elena Fallas Rodríguez from the Broad Front.[15] On December 10, 2015, the organization Front for Equal Rights (Frente Por los Derechos Igualitarios) and a group of deputies from the Citizens' Action Party, the National Liberation Party and the Broad Front presented another bill.[16][17][18] The bill was submitted to the Assembly on January 28, 2016.[19] In December 2016, the Citizens' Action Party (PAC) announced its support for same-sex marriage. Its Equal Marriage project calls for same-sex couples to receive the same rights as opposite-sex couples, including adoption.[20] A few days later, President Luis Guillermo Solís, a member of PAC, announced his personal opposition to same-sex marriage.[21] He did, however, restate his commitment to approving a law of coexistence for same-sex couples.

In April 2017, a Costa Rican citizen and a Mexican citizen who had previously wed in Mexico asked the Costa Rican Embassy in Mexico City to recognize their same-sex marriage. However, the Costa Rican Civil Registry denied their request, based on the country's same-sex marriage ban. In May, the couple appealed the Civil Registry's decision, but it rejected their request again in June. The couple appealed to the Supreme Electoral Court, and said that, should it rule against them, they would appeal to the Supreme Court and then to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights.[22][23]

In November 2017, Costa Rica hosted a conference on the marital rights of same-sex couples across Latin America. Speaking at the conference, Vice President Ana Helena Chacón Echeverría, one of Costa Rica's two vice presidents, announced her support for same-sex marriage.[24]

2018 Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruling

On January 9, 2018, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) ruled that countries signatory to the American Convention on Human Rights are required to allow same-sex couples to marry.[25][26] The ruling states that:

The State must recognize and guarantee all rights derived from a family bond between persons of the same sex in accordance with the provisions of Articles 11.2 and 17.1 of the American Convention. (...) in accordance with articles 1.1, 2, 11.2, 17 and 24 of the American Convention, it is necessary to guarantee access to all the existing figures in domestic legal systems, including the right to marry. (..) To ensure the protection of all the rights of families formed by same-sex couples, without discrimination with respect to those that are constituted by heterosexual couples.

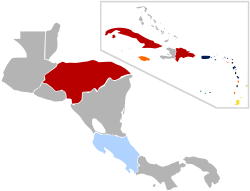

The ruling also set binding precedent for 15 other American countries, who have all ratified the Convention and accepted the Court's jurisdiction, namely Barbados, Bolivia, Chile, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru and Suriname.

The Costa Rican Government announced that it would abide by the ruling.[27][28] Vice President Ana Helena Chacón Echeverría said that the ruling would be adopted in "its totality". The Foreign Ministry notified the Judiciary, the Supreme Electoral Court (responsible for the Civil Registry) and the Legislative Assembly about the ruling on January 12.[29][30]

The first same-sex couple was scheduled to get married on January 20. However, on January 18, the Superior Council of Notaries stated that notaries cannot perform same-sex marriages until provisions in the Family Code prohibiting such marriages are changed by the Parliament or struck down by the Supreme Court.[31][32] This put the Council at odds with the Government and the IACHR, which stated in its ruling that legislative change was not necessary.[33] The couple announced their intention to challenge the Council's decision in the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court (Sala IV).[34] Minister of Justice Marco Feoli reiterated the Government's position that the IACHR ruling was fully binding on Costa Rica.[35]

Reaction

Costa Rica has long been committed to the Inter-American juridical system, and the Constitution of Costa Rica specifically states that the country's international agreements take precedence over national laws. The Costa Rican Supreme Court has repeatedly ruled that the IACHR is the definitive interpreter of the American Convention on Human Rights, and that all of the Court's rulings are fully binding on Costa Rica.[36]

LGBT activists and human rights groups celebrated the IACHR decision, while the Catholic Church and evangelical groups condemned it.[37] The ruling met with outrage among conservative and evangelical groups, who said that the Court had disrespected Costa Rica's laws. Some opponents of the ruling called for the country to leave the jurisdiction of the Court, which would require a constitutional amendment.[38] Constitutional amendments require a two-thirds majority in the Legislative Assembly.[39]

Several supporters of the ruling have argued that local legislation is not required to legalise same-sex marriage, citing a 2016 court decision regarding the legalisation of in vitro fertilisation (IVF), in which the IACHR ruled that presidential and/or governmental decrees are sufficient to implement its decisions.[40][41]

Most of the candidates in the February 2018 presidential elections announced their support for or willingness to respect the IACHR ruling, with the exception of Fabricio Alvarado, Stephanie Campos and Mario Rendondo, all of them from minor Christian parties. Other candidates had already been in favor of same-sex marriage before the IACHR ruling, including former Labor and Social Security Minister Carlos Alvarado Quesada from the governing Citizens' Action Party (PAC), left-leaning Deputy Edgardo Araya and labor union activist Jhon Vega. The rest of the candidates signaled that they were personally opposed to same-sex marriage but willing to accept the Court's ruling. Fabricio Alvarado, an evangelist of the National Restoration Party, claimed that the Court had "violated" Costa Rica's sovereignty. In the days following the IACHR ruling, Alvarado began polling in first place with 17%, up from 3-5% prior to the ruling.[42] Support for Carlos Alvarado, a pro-same-sex marriage candidate, also increased considerably.[43]

In the current Legislative Assembly, eight of the ten PAC deputies and José María Villalta, the sole Broad Front deputy, support same-sex marriage.[44][45] The remaining two PAC deputies and all the deputies of the National Liberation Party (PLN), Social Christian Unity Party (PUSC), Social Christian Republican Party (PRSC) and National Integration Party (PIN) expressed their support for same-sex civil partnerships only.[44] Of the 14 deputies of the ultra-conservative National Restoration, 12 did not answer and two expressed their opposition to same-sex marriage without clarifying if they would support same-sex civil partnerships.[44][46]

In the 1 April 2018 presidential runoff between Carlos Alvarado and Fabricio Alvarado, dubbed by some media outlets as a "de facto referendum on same-sex marriage", same-sex marriage supporter Carlos Alvarado won with over 60% of the vote.[47][48] Following his win, he said: "I will lead a government for all [men] and all [women]. That shelters all people, without any distinction."

2018 Supreme Court ruling

On January 24, the Center for Justice and International Law (Cejil) asked the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court (Sala IV) to rule on the issue of same-sex marriage quickly.[49] On January 25, the Superior Council of Notaries clarified its position, stating that notaries could not perform same-sex marriages until the Civil Registry issued guidelines on the registration of such marriages.[50] Despite this, one same-sex couple successfully married before a notary in February 2018.[51] The notary in question faced an investigation, but rejected any wrongdoing, stating that he respected international law and took a stand against discrimination when marrying the couple.[52] The marriage was later annulled.[53] An additional eight same-sex couples have applied for marriage certificates, as of May 2018.[54]

On February 22, 2018, La Nación reported that the Sala IV was reviewing six lawsuits seeking the legalisation of same-sex marriage in the country.[55] On March 9, 2018, the Attorney General recommended to the court to abide by the IACHR ruling and declare article 14 of the Family Code, which prohibits same-sex marriage, unconstitutional.[56][57] On May 14, 2018, the Supreme Electoral Court stated that same-sex couples could not get married unless Article 14 of the Family Code was either repealed by the Legislative Assembly or struck down by the Supreme Court.[58][59][60]

On July 18, it was announced that the Sala IV would rule on two lawsuits from 2013 and 2015 challenging the constitutionality of Articles 14 and 242 of the Family Code, as well as Article 4 of the 2013 Law of Young People, in the first half of August 2018.[61][62] On August 3, the Commissioner for LGBTI Population Affairs of the Presidency of the Republic, Luis Salazar, presented a letter asking the Sala IV to legalize same-sex marriage, signed by 182 personalities, including former presidents Luis Guillermo Solís, Laura Chinchilla, Óscar Arias and Abel Pacheco.[63][64][65] On August 8, 2018, the Sala IV declared all three of the articles in question unconstitutional, and gave the Legislative Assembly 18 months to amend the laws accordingly. If the Assembly does not comply, both same-sex marriage and same-sex de facto unions will automatically become legal when the deadline passes.[66][67] The ruling was welcomed by President Carlos Alvarado Quesada, but several lawmakers expressed doubts that the Legislative Assembly would amend the law before the deadline.[68][69] The President announced that a extraordinary session would be convened to address the legalisation of same-sex marriage.[70]

Public opinion

A poll conducted between January 4 and 10, 2012, by La Nación showed that 55% of Costa Ricans supported the statement "same-sex couples should have the same rights as heterosexual couples", while 41% were opposed. Support was higher among people aged 18–34, at 60%.[71]

According to Pew Research Center survey, conducted between November 9 and December 19, 2013, 29% of Costa Ricans supported same-sex marriage, 61% were opposed.[72][73]

A poll carried out in August 2016 by the Centro de Investigación y Estudios Políticos (CIEP) indicated that 49% of Costa Ricans opposed the legal recognition of same-sex marriage, while 45% supported it. 6% were unsure.[74]

A poll published in January 2018 by CIEP suggested that 35% of the Costa Rican population supported same-sex marriage, with 59% opposed.[75][76]

See also

References

- ↑ "Costa Rica, Nicaragua Daily News–The Tico Times, Same-sex union advocate slams Costa Rica church for stoking opposition". Ticotimes.net. May 12, 2009. Retrieved October 28, 2010.

- ↑ "Opponents Block Debate On Gay Unions In Costa Rica". On Top Magazine.

- ↑ Kuo, Lily. "Costa Rica could be the first Central American country to allow gay civil unions—by accident".

- ↑ "Costa Rica Accidentally Approves Same-Sex Unions". The Huffington Post. July 3, 2013. Retrieved July 5, 2013.

- ↑ (in Spanish) Presidenta ya firmó ley que podría legalizar derechos a homosexuales

- ↑ "Costa Rica Passes Legislation Permitting Gay Civil Unions -- By Accident". Fox News Latino. 5 July 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ↑ "Costa Rican legislature accidentally passes gay marriage legalization". Tico Times. 3 July 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ↑ Costa Rican lawyers claim 'accidental' bill does nothing for same-sex unions

- ↑ "Gobierno convocará proyecto de unión gay al Congreso en enero, confirma vicepresidenta - Crhoy.com".

- ↑ www.diarioextra.com. "Diario Extra - Buscan reformar Código de Familia para aprobar unión gay". www.diarioextra.com.

- ↑ "Costa Rica Recognizes First Gay Common-Law Marriage With Central America's First Legally Recognized Same-Sex Relationship". June 3, 2015.

- ↑ (in Spanish) Juez que validó unión de hecho de pareja gais resultó exonerado de resolver contra la ley

- ↑ (in Spanish) PUSC anuncia proyecto de ley que crea uniones civiles para parejas homosexuales

- ↑ "High Court Rules against Same-Sex Marriage".

- ↑ (in Spanish) Proyecto de ley N.°19.508

- ↑ (in Spanish) Proyecto de organizaciones sociales para Matrimonio Igualitario ya está en la Asamblea Legislativa

- ↑ (in Spanish) 12 Diputados respaldan proyecto de ley para permitir matrimonio gay

- ↑ (in Spanish) Proyecto de Ley Matrimonio Igualitario by Frente Por los Derechos Igualitarios

- ↑ "Proyecto de ley N.° 19852".

- ↑ (in Spanish) Matrimonio igualitario quiebra a la fracción legislativa del PAC

- ↑ (in Spanish) Presidente de Costa Rica no apoya matrimonio igualitario

- ↑ (in Spanish) Tico busca que su matrimonio con mexicano sea reconocido en Costa Rica

- ↑ (in Spanish) Tico pide que Costa Rica le reconozca matrimonio homosexual con mexicano

- ↑ "Costa Rica vice president champions LGBT, human rights". Washington Blade. November 13, 2017.

- ↑ "Inter-American Court endorses same-sex marriage; Costa Rica reacts". Tico Times. Retrieved January 12, 2018.

- ↑ Andres Pretel, Enrique. "Latin American human rights court urges same-sex marriage legalization". Retrieved January 12, 2018.

- ↑ "Corte Interamericana de DD. HH: Costa Rica debe garantizar plenos derechos a población LGBTI". Teletica. January 9, 2018. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ↑ Ramírez, Luis (January 9, 2018). "Implementar matrimonio gay como pide Corte IDH no requiere del Congreso, según gobierno". Amelia Rueda. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ↑ "Costa Rica's Foreign Ministry Initiates Notification Process To Execute Court Order On Gay Marriage". Q Costa Rica. January 12, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- ↑ López, Ronny (January 12, 2018). "Gobierno ordena a instituciones aplicar criterio de CIDH sobre matrimonio gay". AM Prensa. Retrieved January 14, 2018.

- ↑ Oviedo, Esteban (January 19, 2018). "Consejo Notarial prohíbe a notarios celebrar matrimonios gais". La Nación. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- ↑ Pretel, Enrique Andres (January 19, 2018). "Costa Rica's first gay marriage suffers bureaucratic hitch". Reuters. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- ↑ (in Spanish) Implementar matrimonio gay como pide Corte IDH no requiere del Congreso, según gobierno

- ↑ Recio, Patricia (January 19, 2018). "Pareja gay cancela matrimonio por prohibición de Consejo Notarial y acudirá a la Sala IV". La Nación. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- ↑ Sequeira, Aarón (January 19, 2018). "Ministro de Justicia llama a cuentas a directivo notarial que prohibió celebrar matrimonios gais". La Nación. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- ↑ Inverting Human Rights: The InterAmerican Court versus Costa Rica

- ↑ "Comunidad LGBTI celebra en la Fuente de la Hispanidad determinación de la Corte IDH".

- ↑ "¿Respetarían los candidatos la orden de la Corte IDH sobre matrimonio igualitario?".

- ↑ Costa Rica's Constitution of 1949 with Amendments through 2011

- ↑ (in Spanish) ¿Respetarían los candidatos la orden de la Corte IDH sobre matrimonio igualitario?

- ↑ New Court Ruling Challenges IVF Ban in Costa Rica

- ↑ (in Spanish) Candidato evangélico reconoce que oposición a matrimonio gay le catapultó

- ↑ Arrieta, Esteban (16 January 2018). "Derechos gais elevan acciones del PAC y Restauración". La República. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Elección de diputados". Nacion.com. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ↑ (in Spanish) Sólo 9 diputados apoyan matrimonio igualitario

- ↑ Arrieta, Esteban (17 January 2018). "Matrimonio gay depende de Sala IV". La República. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ Costa Rica Election Hands Presidency to Governing Party Stalwart, The New York Times, April 1, 2018

- ↑ Centre-left wins Costa Rica poll after battle over same-sex marriage, The Sydney Morning Herald, April 2, 2018

- ↑ "Cejil pide a Sala Constitucional de Costa Rica fallo sobre matrimonio gay". January 24, 2018.

- ↑ "Dirección de Notariado espera orden del Registro Civil para dar luz verde a matrimonio gay - Semanario Universidad". January 26, 2018.

- ↑ (in Spanish) "Estamos haciendo valer un derecho": primer matrimonio igualitario de Costa Rica

- ↑ (in Spanish) Dirección de Notariado abre “proceso de fiscalización” a notario que casó a pareja gay

- ↑ (in Spanish) Costarricenses ven con preocupación el futuro económico del país

- ↑ (in Spanish) 9 gay marriage requests are lined up in the Civil Registry

- ↑ Madrigal, Rebeca (February 22, 2018). "Sala IV estudia seis acciones de personas que reclaman validez del matrimonio gay". La Nación. Retrieved February 23, 2018.

- ↑ Sequeira, Aarón (May 12, 2018). "Procuraduría responde a Sala IV sobre uniones gais: opiniones de Corte IDH son vinculantes". La Nación. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- ↑ Madrigal Mena, Luis Manuel (May 12, 2018). "Procuraduría recomienda a la Sala IV acatar criterio de la CorteIDH sobre matrimonio igualitario". delfino.cr. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- ↑ "TSE se pronuncia sobre Opinión Consultiva de la Corte IDH". Supreme Electoral Court. May 14, 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ↑ Madrigal, Rebeca; Oviedo, Esteban (May 14, 2018). "TSE permitirá a ciudadanos cambiarse el nombre según el género autopercibido". La Nación. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- ↑ Arrieta, Esteban (May 14, 2018). "TSE dice no a matrimonio igualitario y deja asunto en manos de la Sala IV". La República. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- ↑ Salas, Yeryis (July 18, 2018). "Sala IV resolverá en agosto sobre uniones de hecho y matrimonios entre personas del mismo sexo". La Nación. Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- ↑ "Sala IV ya sabe cuándo se pronunciará sobre matrimonio gay". CRHoy.com. July 18, 2018. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- ↑ Sequeira, Aarón (August 3, 2018). "Cuatro expresidentes firman declaración a favor del matrimonio igualitario impulsada desde Presidencia". La Nación. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- ↑ Arrieta, Esteban (August 3, 2018). "Expresidentes y otras figuras piden a Sala IV validar matrimonio igualitario". La República. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- ↑ "Personalidades suscriben: "Declaración por la igualdad y no discriminación a parejas del mismo sexo"". Government of Costa Rica. August 3, 2018. Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- ↑ Chinchilla, Sofía (9 August 2018). "Sala IV da 18 meses para que entre en vigencia el matrimonio homosexual". La Nación. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ↑ Madrigal Mena, Luis Manuel (August 8, 2018). "Sala IV da 18 meses para aprobar matrimonio igualitario o aplicará lo dicho por Corte IDH". delfino.cr. Retrieved August 8, 2018.

- ↑ "Costa Rica Supreme Court rules gay marriage ban unconstitutional". Deutsche Welle. 10 August 2018.

- ↑ "Costa Rica's high court: Same-sex marriage should be legal (someday)". The Tico Times. 10 August 2018.

- ↑ (in Spanish) Carlos Alvarado convocará a sesiones extraordinarias proyecto de ley para avalar matrimonio igualitario

- ↑ Ávalos, Ángela (February 12, 2012). "55% a favor de igualdad en derechos". La Nación (in Spanish). Retrieved February 13, 2012.

- ↑ "Chapter 5: Social Attitudes". November 13, 2014.

- ↑ "Appendix A: Methodology". November 13, 2014.

- ↑ (in Spanish) Se mantienen actitudes conservadoras en Costa Rica sobre matrimonio igualitario y Estado laico

- ↑ With pro-gay marriage presidential win, Costa Rica halted religious conservatism

- ↑ (in Spanish) Mayoría de ticos se oponen a matrimonio homosexual y legalización de marihuana