Reverse Underground Railroad

Tearing up the free-born and manumission papers and kidnapping of a free black, in the U.S. free states, to be sold into Southern slavery, from an 1838 abolitionist anti-slavery almanac | |

| Date | 1780–1865 |

|---|---|

| Location | Northern United States and Southern United States |

| Participants | illegal slave trader kidnappers, police, criminals, and captured free blacks |

| Outcome | The forced resettlement of free negro and fugitive slave African Americans into Southern slavery, ending with the Union victory at the end of the American Civil War and the passing of the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery and the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution giving them full citizenship rights. |

| Deaths | ? |

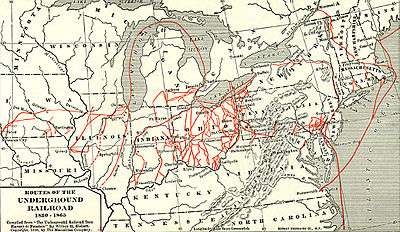

The Reverse Underground Railroad was the pre-American Civil War practice of kidnapping free blacks and fugitive slaves from U.S. free states and slave states and transporting them into or within the Southern slave states for sale as slaves. Three types of kidnapping methods were employed which included physical abduction and inveiglement (kidnapping through trickery) of free blacks and slave-catchers using kidnapping in apprehending run away slaves.[1][2] The Reverse Underground Railroad operated for eighty-five years, from 1780–1865. The name is a reference to the Underground Railroad, the informal network of abolitionists and sympathizers who helped smuggle escaped slaves to freedom, generally in Canada[3] but also in Mexico[4] where slavery had been abolished.

Prevalence

Free African-Americans were often kidnapped from the northern free states along the border of the slave states of Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri because of their relative closeness to the South but kidnapping was also prevalent in states further north such as New York, Pennsylvania, and Illinois as well as in some of the Southern states such as Tennessee.

Mid-Atlantic states

New York and Pennsylvania

Free blacks in New York City and Philadelphia were particularly vulnerable to kidnapping. In New York, a gang known as 'the black-birders' regularly waylaid men, women and children, sometimes with the support and participation of policemen and city officials.[5] In Philadelphia, black newspapers frequently ran missing children notices, including one for the 14-year-old daughter of the newspaper's editor.[6] Children were particularly susceptible to kidnapping; in a two-year period, at least a hundred children were abducted in Philadelphia alone.[7]

Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia

From 1811 to 1829, Martha "Patty" Cannon was the leader of a gang that kidnapped slaves and free blacks, from the Delmarva Peninsula of Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and Chesapeake Bay and transported and sold them to plantation owners located further south. She was indicted for four murders in 1829 and died in prison, while awaiting trial, purportedly a suicide via arsenic poisoning.

Midwestern states

Illinois

John Hart Crenshaw was a large landowner, salt maker, and slave trader, from the 1820s to the 1850s, based out of the southeastern part of Illinois in Gallatin County and a business associate of Kentucky lawman and outlaw, James Ford. Crenshaw and Ford were allegedly kidnapping free blacks in southeastern Illinois and selling them in the slave state of Kentucky. Although, Illinois was a free state, Crenshaw leased the salt works in nearby Equality, Illinois from the U.S. Government, which permitted the use of slaves for the arduous labor of hauling and boiling salt brine water from local salt springs to produce salt. Due to Crenshaw's keeping and "breeding" of slaves and kidnapping of free blacks, who were then pressed into slavery, his house became popularly known as The Old Slave House and is thought to be haunted.

Other cases of the Reverse Underground Railroad in Illinois occurred in the southwestern and western parts of the state, along the Mississippi River bordering the slave state of Missouri. In 1860, John and Nancy Curtis were arrested for trying to kidnap their own freed slaves in Johnson County, Illinois to sell back into slavery in Missouri.[8] Free blacks were also kidnapped in Jersey County, Illinois and taken away to be sold as slaves in Missouri.[9]

Southern states

Tennessee

In the 1820s–1830s, John A. Murrell led an outlaw gang in western Tennessee. He was once caught with a freed slave living on his property. His tactics were to kidnap slaves from their plantations, promise them their freedom, and instead sell them back to other slave owners. If Murrell was in danger of being caught with kidnapped slaves, he would kill the slaves to escape being arrested with stolen property, which was considered a major crime in the Southern United States. In 1834, Murrell was arrested and sentenced to ten years in the Tennessee State Penitentiary in Nashville for slave-stealing.

Florida

In 1844, Jonathan Walker, a Massachusetts abolitionist who helped slaves to escape on his ship in the slave state of Florida was arrested in Pensacola. As his punishment under the law, Walker was branded by a U.S. marshal on the palm of his right hand with the letters "SS" for slave stealer and later released.[10]

Routes

The 1827 newspaper The African Observer described how several Philadelphia children were lured on board a small sloop, at anchor in the Delaware River, with the promise of peaches, oranges and watermelons, then immediately put into the hold of the ship in chains, where they took a week long journey by ship. Once landed, they were marched through brushwood, swamp and cornfields to the home of Joe Johnson and Jesse and Patty Cannon, on the line between Delaware and Maryland, where they were 'kept in irons for a considerable amount of time.' From there, they were again put on board another vessel for a week or more, where one of the children heard someone talking about Chesapeake Bay, in Maryland. Once landed, they were marched again for 'many hundred miles' through Alabama until they reached Rocky Springs, Mississippi.

The same article described a chain of Reverse Underground Railroad posts "established from Pennsylvania to Louisiana."[11]

In the West, kidnappers rode the waters of the Ohio River, stealing slaves in Kentucky and kidnapping free people in Southern Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, who were then transported to the slave states.[12]

Prevention and rescue

The Protecting Society of Philadelphia, an auxiliary of the anti-slavery organization the Abolition Society of Philadelphia, was established in 1827 for "the prevention of kidnapping and man-stealing."[13] In January, 1837, The New York Vigilance Committee, established because any free black person was at risk for being kidnapped, reported that it had protected 335 persons from slavery. David A Ruggles, a black newspaper editor and treasurer of the organization, writes in his paper of his futile attempts to convince two New York judges to prevent illegal kidnapping, as well as a daring successful physical rescue of a young girl named Charity Walker from the New York home of her captors.[14]

From Philadelphia, high constable Samuel Parker Garrigues took several trips to Southern states at the behest of mayor Joseph Watson to rescue children and adults who had been kidnapped from the city's streets. He also successfully went after their abductors. One such case was Charles Bailey, kidnapped at fourteen in 1825 and finally rescued by Garrigues after a three-year search. Unfortunately, the beaten and emaciated youth died a few days after being brought back to Philadelphia. Garrigues was able to find and arrest Bailey's abductor, Captain John Smith, alias Thomas Collins, head of "The Johnson Gang".[15] He also tracked down and arrested John Purnell of the Patty Cannon gang.[16]

In popular culture

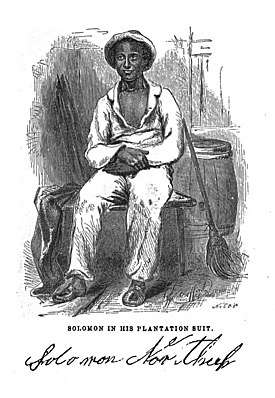

In 1853, Solomon Northrup published Twelve Years A Slave, a memoir of his kidnapping from New York and twelve years spent as a slave in Louisiana. His book sold 30,000 copies upon release.[17] His narrative was made into a 2013 film, which won three Academy Awards.[18] Comfort: A Novel of the Reverse Underground Railroad by H. A. Maxson and Claudia H. Young came out in 2014.

Notable illegal slave trader kidnappers and illegal slave breeders

- Patty Cannon and Cannon-Johnson Gang

- John Hart Crenshaw

- John A. Murrell

- "Uncle Bob" Wilson

Notable victims

Gallery

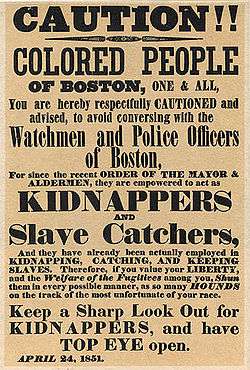

An April 24, 1851 abolitionist poster warning the "Colored People of Boston" about policemen acting as "Kidnappers and Slave Catchers".

An April 24, 1851 abolitionist poster warning the "Colored People of Boston" about policemen acting as "Kidnappers and Slave Catchers".

John A. Murrell of western Tennessee.

John A. Murrell of western Tennessee. John Hart Crenshaw, of southeastern Illinois, with his wife, Francine "Sina" Taylor.

John Hart Crenshaw, of southeastern Illinois, with his wife, Francine "Sina" Taylor. John Hart Crenshaw's Hickory Hill mansion, in Gallatin County, Illinois, infamously known as the "Old Slave House".

John Hart Crenshaw's Hickory Hill mansion, in Gallatin County, Illinois, infamously known as the "Old Slave House". Solomon Northup, a free black born in New York who was later kidnapped by slave catchers.

Solomon Northup, a free black born in New York who was later kidnapped by slave catchers. An illustration from Twelve Years A Slave, the memoir of Solomon Northup, 1853: "Rescues Solomon from Hanging".

An illustration from Twelve Years A Slave, the memoir of Solomon Northup, 1853: "Rescues Solomon from Hanging". A typical 19th century slave auction in the Southern United States.

A typical 19th century slave auction in the Southern United States.

See also

References

- ↑ Wilson, Carol (1994). "Freedom at Risk: The Kidnapping of Free Blacks in America, 1780–1865". Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. pp. 11–16.

- ↑ Musgrave, Jon. "Black Kidnappings in the Wabash and Ohio Valleys of Illinois, Research Paper for Dr. John Y. Simon's Seminar in Illinois History, Southern Illinois University, April–May 1997". Carbondale, IL.

- ↑ Cross, L.D. (2010). "The Underground Railroad: The long journey to freedom in Canada". Toronto, ON: James Lorimer Limited, Publishers. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - ↑ Leanos Jr., Reynaldo (2017). "This underground railroad took slaves to freedom in Mexico, PRI's The World, Public Radio International, March 29, 2017". Minneapolis, MN: Public Radio International.

- ↑ Manisha Sinha, The Untold History Beneath 12 Years, The New York Daily News, March 2, 2013

- ↑ Frankie Hutton, The Early Black Press in America, 1827 to 1860, Greenwood Publishing, 1993, p. 152

- ↑ "Kidnapping in Pennsylvania", Africans in America, PBS.org

- ↑ Lehman, Christopher P. (2011). "Slavery in the Upper Mississippi Valley, 1787–1865: A History of Human Bondage in Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota and Wisconsin". Jefferson, NC: McFarland. p. 166.

- ↑ Hamilton, Oscar Brown (1919). "History of Jersey County, Illinois". Munsell Publishing Company. p. 189.

- ↑ Oickle, Alvin F. (1899). "Jonathan Walker: The Man with the Branded Hand". Rochester, N Y: H. L. Wilson printing company.

- ↑ Lewis, Enoch, "Kidnapping," The African Observer, Vol. 1–12, p. 39, 1827

- ↑ Harold, Stanley, Border War:Fighting Over Slavery Before the Civil War p. 53, University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

- ↑ Frankie Hutton, The Early Black Press in America, 1827 to 1860, p. 152 Greenwood Publishing Group, 1993

- ↑ Hutton, p. 152

- ↑ Hutton p. 153

- ↑ Michael Morgan, Delmarva's Patty Cannon: The Devil on the Nanticoke, Arcadia Publishing, 2015, p. 3

- ↑ Northup, Solomon. Twelve Years a Slave: Summary, online text at Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina, accessed 19 July 2012

- ↑ Cieply, Michael; Barnesmarch, Brooks (March 2, 2014). "‘12 Years a Slave’ Claims Best Picture Oscar". The New York Times.

- Berry, Daina Ramey. The Price for Their Pound of Flesh: The Value of the Enslaved from Womb to Grave in the Building of a Nation. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2017.

- Blackmore, Jacqueline. African American and Race Relations in Gallatin County, Illinois: from the 18th century to 1870. Ann Arbor: Proquest, 1996.

- Campbell, Stanley W. The Slave Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850–1860. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press Books, 2012.

- Collins, Winfield Hazlitt. The domestic slave trade of the southern states. Broadway Publishing Company, 1904.

- Diggins, Milt. Stealing Freedom Along the Mason–Dixon Line: Thomas McCreary, the Notorious Slave Catcher from Maryland. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015.

- Fiske, David. Solomon Northup's Kindred: The Kidnapping of Free Citizens before the Civil War: The Kidnapping of Free Citizens before the Civil War. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2016.

- Fiske, David, Clifford W Brown Jr., and Rachel Seligman. Solomon Northup: The Complete Story of the Author of Twelve Years A Slave: The Complete Story of the Author of Twelve Years a Slave. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2013

- Giles, Ted. Patty Cannon: Woman of Mystery. Easton Publishing Company, 1965.

- Harrold, Stanley. Border War: Fighting over Slavery before the Civil War]. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

- Maddox, Lucy. The Parker Sisters: A Border Kidnapping. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2016.

- Morgan, Michael. Delmarva's Patty Cannon: The Devil on the Nanticoke. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2015.

- Musgrave, Jon. Slaves, Salt, Sex and Mr. Crenshaw: The Real Story of the Old Slave House and America's Reverse Underground R. R. IllinoisHistory.com, 2004.

- Musgrave, Jon. "Black Kidnappings in the Wabash and Ohio Valleys of Illinois". Research Paper presented at Dr. John Y. Simon's Seminar in Illinois History at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale, April–May 1997, Carbondale, IL.

- Musgrave, Jon. Potts Hill Gang, Sturdivant Gang, and Ford's Ferry Gang Rogue's Gallery, Hardin County in IllinoisGenWeb. Springfield, IL: The Illinois Gen Web Project, 2018.

- Penick, James L. The great western land pirate: John A. Murrell in legend and history. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1981.

- Phares, Ross. Reverend Devil: Master Criminal of the Old South. Gretna, LA: Publisher Pelican Publishing, 1941.

- Slaughter, Thomas P. Bloody Dawn: The Christiana Riot and Racial Violence in the Antebellum North. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Stewart, Virgil A. The history of Virgil A. Stewart: and his adventure in capturing and exposing the great "western land pirate" and his gang... New York, NY: Harper and Brothers, 1836.

- Wellman, Paul L. Spawn of Evil. New York, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1964.

- Wilson, Carol. Freedom at Risk: The Kidnapping of Free Blacks in America, 1780–1865. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1994.