Harem

Harem (Arabic: حريم ḥarīm, "a sacred inviolable place; harem; female members of the family"), also known as zenana in South Asia, properly refers to domestic spaces that are reserved for the women of the house in a Muslim family and are inaccessible to adult males except for close relations. This private space has been traditionally understood as serving the purposes of maintaining the modesty, privilege, and protection of women. A harem may house a man's wife—or wives and concubines, as in royal harems of the past—their pre-pubescent male children, unmarried daughters, female domestic workers, and other unmarried female relatives. In former times, some harems were guarded by eunuchs (castrated men) who were allowed inside. Similar institutions have been common in other Mediterranean and Middle Eastern civilizations, especially among royal and upper-class families and the term is sometimes used in non-Islamic contexts. The structure of the harem and the extent of monogamy or polygamy has varied depending on the family's personalities, socio-economic status, and local customs.[1]

Although the institution has experienced a sharp decline in the modern era, seclusion of women is still practiced in some parts of the world, such as rural Afghanistan and conservative states of the Gulf region.[2]

In the West, Orientalist imaginary conceptions of the harem as a fantasy world of forbidden sexuality where numerous women lounged in suggestive poses have influenced many paintings, stage productions, films and literary works. Several European Renaissance paintings dating to the 16th century defy Orientalist tropes and portray the women of the Ottoman harem as individuals of status and political significance.[3] In many periods of Islamic history women in the harem exercised various degrees of political power.[4]

Etymology

The word has been recorded in the English language since early 17th century. It comes from the Arabic ḥarīm, which can mean "a sacred inviolable place", "harem" or "female members of the family". In English the term harem can mean also "the wives (or concubines) of a polygamous man." The triliteral Ḥ-R-M appears in other terms related the notion of interdiction such as haram (forbidden), mahram (unmarriageable relative), ihram (a pilgrim's state of ritual consecration during the Hajj) and al-Ḥaram al-Šarīf ("the noble sanctuary", which can refer to the Temple Mount or the sanctuary of Mecca).[5]

In Turkish of the Ottoman era, the harem, i.e., the part of the house reserved for women was called haremlık, while the space open for men was known as selamlık.[6]

Some scholars have used the term to refer to polygynous royal households throughout history.[7] In Muscovite Russia the area of aristocratic houses where women were secluded was known as terem.[8]

Historical background

.jpg)

The idea of harem or seclusion of women did not originate with Muhammad or Islam. [4] These practices were well established amongst the upper classes of Iraq, the Byzantine Empire, Ancient Greece and Persia for thousands of years before the advent of Islam.

The practice of secluding women was common to many ancient near eastern communities, especially where polygamy was permitted.[9] In pre-Islamic Assyria, Persia, and Egypt, most royal courts had a harem, where the ruler’s wives and concubines lived with female attendants, and eunuchs.[4] South Asian traditions of female seclusion, called purdah, may have been influenced by Islamic customs, but the practice of segregation by gender predates the Islamic invasions of India.[10] The practice of female seclusion is not exclusive to Islam, but the English word harem denotes the domestic space reserved for women in Muslim households.[11][12]

The harem system first became fully institutionalized in the Islamic world under the Abbasid caliphate.[2] Some scholars believe that Islamic culture adopted the custom of secluding women from the Byzantine Empire and Persia, and then read those customs back into the Quran.[13] According to Eleanor Doumato, the practice of secluding women in Islam is based on both religious tradition and social custom.[2]

Although the term harem does not denote women's quarters in the Quran, some scholars point out that a number of Quranic verses discussing modesty and seclusion were held up by Quranic commentators as religious rationale for the separation of women from men.[2][14] One verse in particular discusses hijab. In modern usage hijab colloquially refers to the religious attire worn by Muslim women, but its original meaning was a "veil" or "curtain" that physically separates female from male space.[15][11] Although classical commentators agreed that these verses referred specifically to Muhammad's wives, they usually viewed them as providing a model for all Muslim women.[2][16]

Moulay Ismail, Alaouite sultan of Morocco from 1672 to 1727, had over 500 concubines.[17] He is said to have fathered a total of 525 sons and 342 daughters by 1703 and achieved a 700th son in 1721.[18]

The practice of female seclusion witnessed a sharp decline in the early 20th century as a result of education and increased economic opportunity for women, but it is still practiced in some parts of the world, such as rural Afghanistan and conservative states of the Persian Gulf region.[2]

The ideal of seclusion

Leila Ahmed describes the ideal of seclusion as a "a man's right to keep his women concealed—invisible to other men." Ahmed identifies the practice of seclusion as a social ideal and one of the four factors that shaped the lives of women in the Mediterranean Middle East. [19] For example, contemporary sources from the Byzantine Empire describe the social mores that governed women's lives. Women were not supposed to be seen in public. They were guarded by eunuchs and could only leave the home "veiled and suitably chaperoned." Some of these customs were borrowed from the Persians, but Greek society also influenced the development of patriarchal tradition.[20]

The ideal of seclusion was not fully realized as social reality. One reason for this is because working class women often held jobs that required interaction with men.[11] Women participated in economic life as midwives, doctors, bath attendants and artisans. At times they lent and invested money and engaged in other commercial activities. [21] Female seclusion has historically signaled social and economic prestige.[11]

Eventually, the norms of female seclusion spread beyond the elites, but the practice remained characteristic of upper and middle classes, for whom the financial ability to allow one's wife to remain at home was a mark of high status.[2][11] In some regions, such as the Arabian peninsula, seclusion of women was practiced by poor families at the cost of great hardship, but it was generally economically unrealistic for the lower classes.[2]

Historical records shows that the women of 14th-century Mamluk Cairo freely visited public events alongside men, despite objections of religious scholars.[11]

Ancient Near East

The institution of the harem was widespread in the ancient Near East.[22]

In Assyria, rules of harem etiquette were stipulated by royal edicts. The women of the harem lived in seclusion, guarded by eunuchs, and the entire harem traveled together with the king. A number of regulations were designed to prevent disputes among the women from developing into political intrigues.[22]

There is no evidence of harem practices among early Iranians, but Iranian dynasties adopted them after their conquests in the region. According to Greek sources, the nobility of the Medes kept no less than five wives who were watched over by eunuchs.[22]

Greek historians report that Persian notables of the Achaemenid empire as well as the king himself had several wives and a larger number of concubines. The Old Persian word for the harem is not attested, but it can be reconstructed as xšapā.stāna (lit. night station or place where one spends the night). The chief consort, who was usually the mother of the heir to the throne, was in charge of the household. She had her own living quarters, revenues, and a large staff. Three other groups of women lives in separate quarters: the other legal wives, royal princesses, and concubines.[22]

The Achaemenid harem served as a model for later Iranian empires, and the institution remained almost unchanged. Little is known about the harems of the Parthians, but the information about the Sasanian harem reveals a picture that closely mirrors Achaemenid customs. A peculiar characteristic of the Sasanian royalty and aristocracy, which was attested in later times under the Safavid and Qajar empires, was that the highest female rank was not necessarily given to the chief wife, but could be held by a daughter or a sister.[22]

Of all the Persian kings, Khosrow II was the most extravagant in his hedonism. He searched his realm to find the most beautiful girls, and it was rumored that about 3,000 of them were kept in his harem. This practice was widely condemned and it was counted as one of the crimes for which he was later tried and executed. Khosrow himself claimed that he sent his favorite wife Shirin every year to offer them a possibility of leaving his harem with a dowry for marriage, but that their luxurious lifestyle always prompted them to refuse his offer.[22]

In Islamic cultures

Eunuchs, slavery and imperial harems

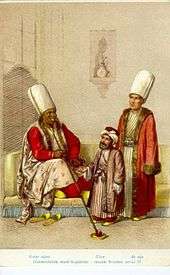

Eunuchs were probably introduced into Islam through the influence of Persian and Byzantine imperial courts.[23] The Ottomans employed eunuchs as guardians of the harem. Istanbul's Topkapı Palace housed several hundred eunuchs in the late-sixteenth century. The head eunuch who guarded the entrance of the harem was known as kızlar ağası.[24] Eunuchs were either Nilotic slaves captured in the Nile vicinity and transported through ports in Upper Egypt, the Sudan and Abyssinia,[25] or European slaves such as Slavs and Franks.[23]

According to Encyclopedia of Islam, castration was prohibited in Islamic law "by a sort of tacit consensus" and eunuchs were acquired from Christian and Jewish traders.[26] Al-Muqaddasi identifies a town in Spain where the operation was performed by Jews and the survivors were then sent overseas.[26] Encyclopedia Judaica states that Talmudic law counts castration among mutilations entitling a slave to immediate release, so that the ability of Jewish slave traders to supply eunuchs to harems depended on whether they could acquire castrated males.[27]

European artists and writers envisioned and presented the Oriental harem in a romanticized, albeit historically inaccurate manner. The dark eunuch was held as the embodiment of the sensual tyranny that held sway in the fantasized Ottoman palace, for he had been "clipped" or "completely sheared" to make of him the "ultimate slave" for the supreme ruler.[28] In the Ottoman court, white eunuchs, who were mostly brought from castration centers in Christian Europe and Circassia, were responsible for much of the palace administration, while black eunuchs, who had undergone a more radical form of castration, were the only male slaves employed in the royal harem.[29]

The chief black eunuch, or the Kizlar Agha, came to acquire a great deal of power within the Ottoman Empire. He not only managed every aspect of the Harem women's lives but was also responsible for the education and social etiquette of the princes and young women in the Harem. He arranged for all ceremonial events within the Harem including weddings and circumcision parties, and even notified women of death sentences when "accused of crimes or implicated in intrigues of jealousy and corruption."[30]

Nineteenth-century travelers accounts tell of being served by black eunuch slaves.[31] The trade was suppressed in the Ottoman Empire beginning in the mid-19th century, and slavery was legally abolished in 1887 or 1888.[32] Late 19th-century slaves in Palestine included enslaved Africans and the sold daughters of poor Palestinian peasants. Both Arabs and Jews owned slaves.[32] Circassians and Abazins from North of the Black Sea may have also be involved in the Ottoman slave trade.[33]

Imperial Harem of the Ottoman Empire

The Imperial Harem of the Ottoman sultan, which was also called seraglio in the West, was part of Topkapı Palace. It also housed the Valide Sultan, as well as the sultan's daughters and other female relatives. Eunuchs and servant girls were also part of the harem. During the later periods, the sons of the sultan lived in the Harem until they were 12 years old.[34]

Some women of Ottoman harem, especially wives, mothers and sisters of sultans, played very important political roles in Ottoman history, and in times it was said that the empire was ruled from harem. Hürrem Sultan (wife of Suleiman the Magnificent, mother of Selim II), was one of the most powerful women in Ottoman history.

It is being more commonly acknowledged today that the purpose of harems during the Ottoman Empire was for the royal upbringing of the future wives of noble and royal men. These women would be educated so that they were able to appear in public as a royal wife.[35]

Sultan Ibrahim the Mad, Ottoman ruler from 1640 to 1648, is said to have drowned 280 concubines of his harem in the Bosphorus.[36][37] At least one of his concubines, Turhan Hatice, a Rus' girl (from the area around modern Ukraine) captured during a Tatar raid and sold into slavery, survived his reign.

In Istanbul, the separation of men's and women's quarters was never practiced among the poor, and by 1920s and 1930s it had become a thing of the past in middle and upper-class homes.[38]

The Mughal Harem

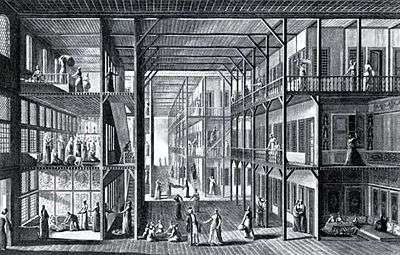

The king's wives, concubines, dancing girls and slaves were not the only women of the Mughal harem. Many others, including the king's mother lived in the harem. Aunts, grandmothers, sisters, daughters and other female relatives of the king all lived in the harem. Male children also lived in the harem until they grew up.[39] Within the precincts of the harem were markets, bazaars, laundries, kitchens, playgrounds, schools and baths. The harem had a hierarchy, its chief authorities being the wives and female relatives of the emperor and below them were the concubines.[40]

Safavid royal harem

The royal harem played an important role in the history of Safavid Persia. In the early Safavid period, young princes were placed in the care of a lala (high-ranking Qizilbash chief who acted as a guardian) and eventually given charge of important governorates.[41] Although this system had the danger of encouraging regional rebellions against the shah, it gave the princes education and training which prepared them for dynastic succession.[41] This policy was changed by Shah Abbas I (1571-1629), who "largely banished" the princes to the harem, where their social interactions were limited to the ladies of the harem and eunuchs.[42] This deprived them of administrative and military training as well as experience of dealing with the aristocracy of the realm, which, together with the princes' indulgent upbringing, made them not only unprepared to carry out royal responsibilities, but often also uninterested in doing so.[42] The confinement of royal princes to the harem was an important factor contributing to the decline of the Safavid dynasty.[41][43]

The administration of the royal harem constituted an independent branch of the court, staffed mainly by eunuchs.[44] These were initially black eunuchs, but white eunuchs from Georgia also began to be employed from the time of Abbas I.[44] The mothers of rival princes together with eunuchs engaged in palace intrigues in an attempt to place their candidate on the throne.[41] From the middle of the sixteenth century, rivalries between Georgian and Circassian women in the royal harem gave rise to dynastic struggles of an ethnic nature previously unknown at the court.[45] When Shah Abbas II died in 1666, palace eunuchs engineered the succession of Suleiman I and effectively seized control of the state.[46][47] Suleiman set up a privy council, which included the most important eunuchs, in the harem, thereby depriving traditional state institutions of their functions.[46] The eunuchs' influence over military and civil affairs was checked only by their internal rivalries and the religious movement led by Muhammad Baqir Majlisi.[47] The royal harem reached such proportions under Sultan Husayn (1668–1726) that it consumed a large part of state revenues.[47] After the fall of the Safavid dynasty, which occurred soon afterwards, eunuchs were never again able to achieve significant political influence as a class in Persia.[47]

Outside Islamic culture

Ashoka, the great emperor of the Mauryan Dynasty in India, kept a harem of around 500 women. Once when a few of the women insulted him, he had all of them burnt to death.[48]

In Mexico, Aztec ruler Montezuma II, who met Cortes, kept 4,000 concubines; every member of the Aztec nobility was supposed to have had as many consorts as he could afford.[49]

Harem is also the usual English translation of the Chinese language term hougong (hou-kung; Chinese: 後宮; literally: "the palace(s) behind"). Hougong refers to the large palaces for the Chinese emperor's consorts, concubines, female attendants and eunuchs. The women who lived in an emperor's hougong sometimes numbered in the thousands. In 1421, Yongle Emperor ordered 2,800 concubines, servant girls and eunuchs who guarded them to a slow slicing death as the Emperor tried to suppress a sex scandal which threatened to humiliate him.[50]

Western representations

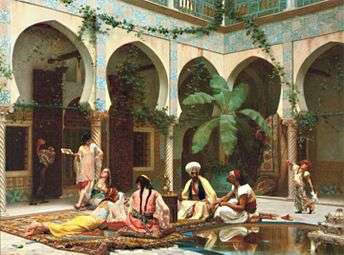

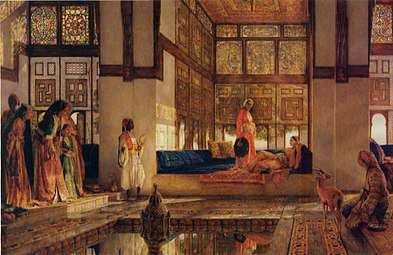

The institution of the harem exerted a certain fascination on the European imagination, especially during the Age of Romanticism, and was a central trope of Orientalism in the arts, due in part to the writings of the adventurer Richard Francis Burton. Images through paintings and later films were particularly powerful ways of expressing these tropes.

A centuries-old theme in Western culture is the depiction of European women forcibly taken into Oriental harems—evident for example in the Mozart opera Die Entführung aus dem Serail ("The Abduction from the Seraglio") concerning the attempt of the hero Belmonte to rescue his beloved Konstanze from the seraglio/harem of the Pasha Selim; or in Voltaire's Candide, in chapter 12 of which the old woman relates her experiences of being sold into harems across the Ottoman Empire.

Much of Verdi's opera Il corsaro takes place in the harem of the Pasha Seid—where Gulnara, the Pasha's favorite, chafes at life in the harem, and longs for freedom and true love. Eventually she falls in love with the dashing invading corsair Corrado, kills the Pasha and escapes with the corsair—only to discover that he loves another woman.

The Lustful Turk, a well-known British erotic novel, was also based on the theme of Western women forced into sexual slavery in the harem of the Dey of Algiers, while in A Night in a Moorish Harem, a Western man is invited into a harem and engages in forbidden sex with nine concubines. In both works, the theme of "West vs. Orient" is clearly interwoven with the sexual themes.

The Sheik novel and the Sheik film, a Hollywood production from 1921, are both controversial and probably the best known works created by exploiting the motif.[51] Much criticism ensued over decades, especially recently, on various strong and unambiguous Orientalist and colonialist elements, and in particularly directed at ideas closely related to the central rape plot in which for women, sexual submission is a necessary and natural condition, and that interracial love between an Englishwoman and Arab, a "native", is avoided, while the rape is ultimately justified by having the rapist turn out to be European rather than Arab.[52][53][54][55]

Image gallery

Many Western artists have depicted their imaginary conceptions of the harem.

- Depictions of Harems

The Pasha in His Harem by Francois Boucher c. 1735-1739

The Pasha in His Harem by Francois Boucher c. 1735-1739 Scene from the Harem, Jean-Baptiste van Mour (1st half of the 18th century)

Scene from the Harem, Jean-Baptiste van Mour (1st half of the 18th century) Scene in a Harem, by Guardi

Scene in a Harem, by Guardi The Harem as imagined by European artist, The Dormitory of the Concubines, by Ignace Melling, 1811.

The Harem as imagined by European artist, The Dormitory of the Concubines, by Ignace Melling, 1811. Gustave Boulanger: The Harem

Gustave Boulanger: The Harem Harem scene by Dominique Ingres

Harem scene by Dominique Ingres The Reception, John Frederick Lewis, 1805-1875, English

The Reception, John Frederick Lewis, 1805-1875, English Scene from the Harem by Fernand Cormon, c. 1877

Scene from the Harem by Fernand Cormon, c. 1877 Harem Scene, Quintana Olleras, 1851-1919, Spanish

Harem Scene, Quintana Olleras, 1851-1919, Spanish The Harem Fountain, Frederick Arthur Bridgman, 1847-1928, American

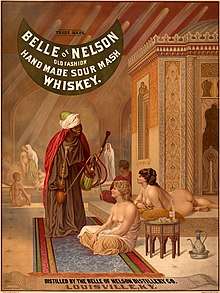

The Harem Fountain, Frederick Arthur Bridgman, 1847-1928, American Belle of Nelson whiskey poster (1878), based on a harem scene by Jean-Léon Gérôme.

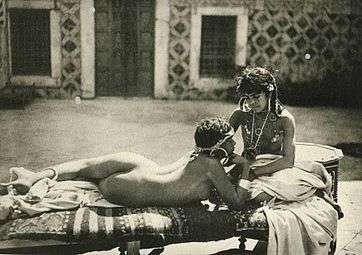

Belle of Nelson whiskey poster (1878), based on a harem scene by Jean-Léon Gérôme. In the harem, Lehnert & Landrock postcard, 1900s-1910s

In the harem, Lehnert & Landrock postcard, 1900s-1910s_-_Ad_6.jpg) The Virgin of Stamboul, 1920 film poster

The Virgin of Stamboul, 1920 film poster

See also

Bibliography

Citations

- ↑ Cartwright-Jones 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Eleanor Abdella Doumato (2009). "Seclusion". In John L. Esposito. The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Madar 2011.

- 1 2 3 Britannica 2002.

- ↑ Wehr 1976, pp. 171-172.

- ↑ Quataert 2005, p. 152.

- ↑ Betzig 2013.

- ↑ Fay 2012, pp. 38-39.

- ↑

- ↑ Kumkum Chatterjee. "Purdah". In Colin Blakemore, Sheila Jennett. The Oxford Companion to the Body. p. 570.

Purdah [...] refers to the various modes of shielding women from the sight primarily of men (other than their husbands or men of their natal family) in the South Asian subcontinent. [...] The purdah, as veiling, was possibly influenced by Islamic custom, [...] But, in the sense of seclusion and the segregation of men and women, purdah predates the Islamic invasions of India.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Youshaa Patel (2013). "Seclusion". The Oxford Encyclopedia of Islam and Women. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "harem". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House. Retrieved 2017-04-04.

- ↑ Keddie, Nikki (Spring 1990). "The Past and Present of Women in the Muslim World". 'Journal of World History'. 1 (1): 77–108.

- ↑ Siddiqui, Mona (2006). "Veil". In Jane Dammen McAuliffe. Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān. Brill. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ [Quran 33:53 (Translated by Yusuf Ali)]

- ↑ Schi̇ck, İrvi̇n Cemi̇l (2009). "Space: Harem: Overview". In Suad Joseph. Encyclopedia of Women & Islamic Cultures. Brill. doi:10.1163/1872-5309_ewic_EWICCOM_0283.

- ↑ "Morocco poll - choice or façade?". BBC News. September 1, 2007.

- ↑ "Some magical Moroccan records". Guinness World Records. Guinness World Records Limited. March 3, 2008. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- ↑ Ahmed 1992, p. 103.

- ↑ Ahmed 1992, pp. 26-28.

- ↑ Ahmed 1992, p. 27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 A. Shapur Shahbazi (2012). "HAREM i. IN ANCIENT IRAN". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- 1 2 Marzolph 2004.

- ↑ Rodriguez 1997.

- ↑ Abir, Mordechai (1968). Ethiopia: the era of the princes: the challenge of Islam and re-unification of the Christian Empire, 1769-1855. Praeger. pp. 57–60.

- 1 2 Pellat, Ch., Lambton, A.K.S. and Orhonlu, Cengiz (2012). "K̲h̲āṣī". In P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0499.

- ↑ Arcadius Kahan. "Economic History". Encyclopaedia Judaica. 6.

- ↑ Lad, Jateen (2010). "Panoptic Bodies: Black Eunuchs as Guardians of the Topkapı Harem". In Booth, Marilyn. Harem Histories: Envisioning Places and Living Spaces. Duke University Press. pp. 136–137. ISBN 978-0822348696.

- ↑ Ronald Segal (2002). Islam's Black Slaves: The Other Black Diaspora. Macmillan. p. 109. ISBN 9780374527976.

- ↑ 1892-1960., Penzer, N. M. (Norman Mosley), (2005). The harem : inside the Grand Seraglio of the Turkish sultans. Mineola, N.Y.: Dover. ISBN 978-0486440040. OCLC 57211338.

- ↑ Through Samaria to Galilee and the Jordan: Scenes of the Early Life and Labors of Our Lord, Josias Porter, 1889, Thomas Nelson and Sons, London, Edinburgh, and New York, reprinted by Kessinger Publishing, 2005, p. 242.

- 1 2 Joseph Glass and Ruth Kark. "Sarah La Preta: A Slave in Jerusalem". Jerusalem Quarterly. 34: 41–50.

- ↑ Faroqhi 2011.

- ↑ Ansary 2009, p. 228.

- ↑ Goodwin 1997, p. 127.

- ↑ "Old World Empires: Cultures of Power and Governance in Eurasia". Ilhan Niaz (2014). p.296. ISBN 1317913787

- ↑ Dash, Mike (22 March 2012). "The Ottoman Empire's Life-or-Death Race". Smithsonian.com.

- ↑ Duben & Behar 2002, p. 223.

- ↑ Mukherjee 2001.

- ↑ Sharma, Anjali (28 November 2013). "Inside the harem of the mughals". The New Indian Express.

- 1 2 3 4 R.M. Savory (1977). "Safavid Persia". In P. M. Holt, Ann K. S. Lambton, Bernard Lewis. The Cambridge History of Islam. The Central Islamic Lands from Pre-Islamic Times to the First World War. Volume 1A. Cambridge University Press. p. 424.

- 1 2 H.R. Roemer (1986). "The Safavid Period". In William Bayne Fisher, Peter Jackson, Lawrence Lockhart. The Cambridge History of Iran. Volume 6. Cambridge University Press. pp. 277–278.

- ↑ H.R. Roemer (1986). "The Safavid Period". In William Bayne Fisher, Peter Jackson, Lawrence Lockhart. The Cambridge History of Iran. Volume 6. Cambridge University Press. p. 330.

- 1 2 R.M.Savory (1986). "The Safavid Administrative System". In William Bayne Fisher, Peter Jackson, Lawrence Lockhart. The Cambridge History of Iran. Volume 6. Cambridge University Press. p. 355.

- ↑ R.M.Savory (1986). "The Safavid Administrative System". In William Bayne Fisher, Peter Jackson, Lawrence Lockhart. The Cambridge History of Iran. Volume 6. Cambridge University Press. p. 363.

- 1 2 H.R. Roemer (1986). "The Safavid Period". In William Bayne Fisher, Peter Jackson, Lawrence Lockhart. The Cambridge History of Iran. Volume 6. Cambridge University Press. p. 307.

- 1 2 3 4 A.K.S. Lambton (1978). "K̲h̲āṣī (II.—In Persia)". In P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Encyclopaedia of Islam. 4 (2nd ed.). Brill. p. 1092.

- ↑ Upinder Singh (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th century. Pearson Education. p. 332. ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9.

- ↑ Sex in History, March 1994, Michigan Today

- ↑ "Revenge of the evil emperor: Mass slaughter in Beijing's Forbidden City". Mail Online. May 3, 2008.

- ↑ "The Sheik". University of Pennsylvania Press website. Accessed Oct. 20, 2015.

- ↑ "Sheiks & Terrorists - Reclaiming Identity: Dismantling Arab Stereotypes". www.arabstereotypes.org. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ J., Dajani, Najat Z. (1 January 2000). "Arabs in Hollywood : Orientalism in film". doi:10.14288/1.0099552. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ Hsu-Ming Teo. "Historicizing The Sheik: Comparisons of the British Novel and the American Film". Jprstudies.org. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ Hsu-Ming Teo. "Desert Passions: Orientalism and Romance Novels".

Sources

- Ahmed, Leila (1992). Women and Gender in Islam. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Ansary, Tamim (2009). Destiny disrupted: a history of the world through Islamic eyes. New York: PublicAffairs. p. 228. ISBN 9781586486068.

- Anwar, Etin (2004). "Harem". In Richard C. Martin. Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World. MacMillan Reference USA.

- Betzig, Laura (March 1994). "Sex in History". Michigan Today. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on 11 September 2013.

- Britannica (2002). "Harem". Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- Cartwright-Jones, Catherine (2013). "Harem". The Oxford Encyclopedia of Islam and Women. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref:oiso/9780199764464.001.0001/acref-9780199764464-e-0126 (inactive 2018-09-21).

- Duben, Alan; Behar, Cem (2002). Istanbul Households: Marriage, Family and Fertility, 1880-1940. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521523035.

- Fay, Mary Ann (2012). Unveiling the Harem: Elite Women and the Paradox of Seclusion in Eighteenth-Century Cairo. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815651703.

- Goodwin, Godfrey (1997). The private world of Ottoman women. London: Saqi Books. ISBN 9780863567513.

- Haslauer, Elfriede (2005). "Harem". The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195102345.001.0001/acref-9780195102345-e-0291 (inactive 2018-09-21).

- Faroqhi, Suraiya (2006). The Ottoman Empire and the World Around It.

- Madar, Heather (2011). "Before the Odalisque: Renaissance Representations of Elite Ottoman Women". 'Early Modern Women'. 6: 1–41.

- Marzolph, Ulrich (2004). "Eunuchs". The Arabian Nights Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO.

- Mukherjee, Soma (2001). Royal Mughal ladies and their contributions. New Delhi: Gyan Publishing House. ISBN 9788121207607.

- Quataert, Donald (2005). The Ottoman Empire, 1700-1922. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521839105.

- Rodriguez, J.P. (1997). "Ottoman Empire". The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery. ABC-CLIO.

- Wehr, Hans; Cowan, J. Milton (1976). A Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic (3rd ed.). Spoken Language Services.

Further reading

- Alev Lytle Croutier. Harem: The World Behind the Veil, reprint ed. Abbeville Publishing Group (Abbeville Press, Inc.), 1998. ISBN 1-55859-159-1

- Alan Duben, Cem Behar, Richard Smith (Series Editor), Jan De Vries (Series Editor), Paul Johnson (Series Editor), Keith Wrightson (Series Editor). Istanbul Households: Marriage, Family and Fertility, 1880-1940, new ed. Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-521-52303-6

- John Freely. Inside the Seraglio: Private Lives of the Sultans in Istanbul: The Sultan's Harem, new ed. Penguin (Non-Classics), 2001. ISBN 0-14-027056-6

- Lal, Kishori Saran (1988). The Mughal Harem. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-85179-03-2.

- Reina Lewis. Rethinking Orientalism: Women, Travel, And The Ottoman Harem. Rutgers University Press, 2004 ISBN 9780813535432

- Fatima Mernissi. Dreams of Trespass: Tales of a Harem Girlhood Perseus 1994

- Leslie P. Peirce. The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire, new ed. Oxford University Press USA, 1993. ISBN 0-19-508677-5

- N. M. Penzer. The Harēm : Inside the Grand Seraglio of the Turkish Sultans. Dover Publications, 2005. ISBN 0-486-44004-4

- M. Saalih. Harem Girl : A Harem Girl's Journal reprint ed. Delta, 2002. ISBN 0-595-31300-0

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Harems. |

-Jerusalem-Temple_Mount-Dome_of_the_Rock_(SE_exposure).jpg)