Slavery in the British and French Caribbean

Slavery in the British and French Caribbean refers to slavery in the parts of the Caribbean dominated by France or the British Empire.

History

In the Caribbean, Britain colonised the islands of St. Kitts and Barbados in 1623 and 1627 respectively, and later, Jamaica in 1655. These and other Caribbean colonies became the center of wealth and the focus of the slave trade for the growing English empire.[1]

As of 1778, the French were importing approximately 13,000 Africans for enslavement to the French West Indies.[2]

General overview

The Lesser Antilles islands of Barbados, St. Kitts, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Antigua, Martinique, Guadeloupe, Saint Lucia and Dominica were the first important slave societies of the Caribbean, switching to slavery by the end of the 17th century as their economies converted from tobacco to sugar production. By the middle of the 18th century, British Jamaica and French Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) had become the largest slave societies of the region, rivaling Brazil as a destination for enslaved Africans.

The death rates for black slaves in these islands were higher than birth rates. The decrease averaged about 3 percent per year in Jamaica and 4 percent a year in the smaller islands. The diary of slaveowner Thomas Thistlewood of Jamaica details violence against slaves, and constitutes important historical documentation of the conditions for Caribbean slaves.

For centuries slavery made sugarcane production economical. The low level of technology made production difficult and labor-intensive. At the same time, the demand for sugar was rising, particularly in Great Britain. The French colony of Saint-Domingue quickly began to out-produce all of the British islands combined. Though sugar was driven by slavery, rising costs for the British made it easier for the British abolitionists to be heard.

Anglo-American slavery

The slavery system that developed in the Lesser Antilles was an outgrowth of the demand for sugar and other crops. The Spanish loosened its foothold in the Caribbean during the first half of the 17th century, which allowed the British to settle several islands and to ultimately seize Jamaica in 1655. To protect these investments, the British would later place a contingent of the Royal Navy in Port Royal.[3]

In 1640 the English began sugar production with the help of the Dutch. This started the Anglo-American plantation societies which would later be led by Jamaica after it was fully developed. At its peak production between 1740-1807 Jamaica received 33% of the total slaves that were imported in order to keep up its production. Other crops besides sugar were also cultivated on the plantations. Tobacco, coffee, and livestock were all produced as well using slave labor. Sugar, however, stands out most prominently due to its exorbitant popularity during the time period and the dangers of its production, which claimed the lives of many.[4]

England had multiple sugar islands in the Caribbean, especially Jamaica, Barbados, Nevis, and Antigua, which provided a steady flow of sugar for sale; slave labor produced the sugar.[5] An important result of Britain's victory in the War of the Spanish Succession (1702–1714) was enlarging its role in the slave trade.[6] Of special importance was the successful secret negotiation with France to obtain a 30-year monopoly on the Spanish slave trade, called the Asiento. Queen Anne of Great Britain also allowed her North American colonies like Virginia to make laws that promoted black slavery. Anne had secretly negotiated with France to get its approval regarding the asiento.[7] She boasted to Parliament of her success in taking the asiento away from France and London celebrated her economic coup.[8] Most of the slave trade involved sales to Spanish colonies in the Caribbean, and to Mexico, as well as sales to British colonies in the Caribbean and in North America.[9] Historian Vinita Ricks says the agreement allotted Queen Anne "22.5% (and King Philip V, of Spain 28%) of all profits collected for her personal fortune." Ricks concludes that the Queen's "connection to slave trade revenue meant that she was no longer a neutral observer. She had a vested interest in what happened on slave ships."[10][11]

The slaves incoming to the Anglo-American colonies were at high risk both mentally and physically. The Middle Passage alone accounted for roughly 10% of all deaths. Some experts believe that one out of every three slaves died before ever reaching their African port of departure. It should be mentioned that the majority of Anglo-American slaves came from Western Central Africa. These factors and others caused many slaves on arrival to feel alienated, fragile, and that death was right around the corner. The conditions suffered by slaves during the voyages were hostile. The slaves were placed in close quarters, fed barely enough to sustain them, and oftentimes they fell victim to diseases contracted prior to the voyage. The slaves would not see sunlight during this period and were prone to both weight loss and scurvy.[12]

The living and working conditions in the Lesser Antilles were very harsh for the slaves that were brought in to work the plantations. The average life of a slave after "adjusting" to the climate and environmental conditions of Jamaica was expected to be less than two decades. This was due to their limited familiarly and immune defense against the diseases and illnesses present in Jamaica. Disease decimated incoming slave populations. Attempts were made to help curtail the problem, but ultimately were fruitless.[13]

To help protect their investments, most planters would not immediately give the hardest tasks to the newest slaves. Slave owners would also set up a walled area away from the veteran slaves in order to stymie the spread of disease. These areas would contain 100–200 slaves at any time. Later, after new slaves had been bought, they would be placed into the care of older and more experienced slaves who were already accustomed to the plantation in hopes of increasing their chances for survival. Examples of tasks assigned to new slaves include planting and constructing buildings. Though newer slaves typically formed supportive relationships with veteran slaves taking, these relationships were not always positive, and abuse did occur.

Sugar production in the Lesser Antilles was a very grisly business. On Jamaica from 1829 to 1832 the average mortality rate for slaves on sugar plantations was 35.1 deaths per 1000 enslaved. The most dangerous part of the sugar plantation was the cane planting. Cane planting during this era consisted of clearing land, digging the holes for the plants, and more. Overseers used the whip in an attempt to both motivate and punish slaves. The slaves themselves were also working and living with barely adequate nourishment and in times of hard work would often be starved. This contributed to low birth rates and the high mortality rates for the slaves. Some experts believe that the average infant mortality at plantations to be 50% or even higher. This extremely high rate of infant mortality meant that the slave population that existed in the Lesser Antilles was not self-sustaining, thus requiring a constant importation of new slaves. Living and working conditions on non-sugar plantations was considered to be better, however, only marginally.[14]

Abolition

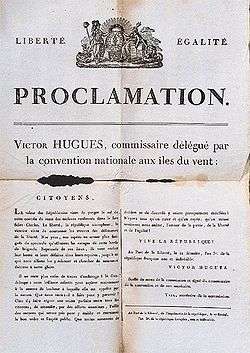

Slavery was first abolished by the French Republic in 1794, but Napoleon revoked that decree in 1802.[15] In 1815, the Republic abolished the slave trade but the decree did not come into effect until 1826.[16] France re-abolished slavery in her colonies in 1848 with a general and unconditional emancipation.[17][18]

William Wilberforce's Slave Trade Act 1807 abolished the slave trade in the British Empire. It was not until the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 that the institution finally was abolished, but on a gradual basis.[19] Since slave owners in the various colonies (not only the Caribbean) were losing their unpaid labourers, the government set aside £20 million for compensation but it did not offer the former slaves reparations.[20][21]

Effects of the abolition

With the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, the new British colony of Trinidad was left with a shortage of labour. This shortage became worse after the abolition of slavery in 1833. To deal with this problem, Trinidad imported indentured servants from the 1810s until 1917. Initially Chinese, free West Africans, and Portuguese from the island of Madeira were imported, but they were soon supplanted by Indians who started arriving from 1845. Indentured Indians would prove to be an adequate alternative for the plantations that formerly relied upon slave labour. In addition, numerous former slaves migrated from the Lesser Antilles to Trinidad to work.

In 1811 on Tortola in the British Virgin Islands, Arthur William Hodge, a wealthy plantation owner and Council member, became the first person to be hanged for the murder of a slave.

Whitehall in Britain announced in 1833 that the gradual abolition would end by 1840; by then, and slaves in its territories would be totally freed. In the meantime, the government told slaves they had to remain on their plantations and would have the status of "apprentices" for the next six years. On 1 August 1834 in Trinidad, an unarmed group of mainly elderly Negroes being addressed by the Governor at Government House about the new apprenticeship laws, began chanting: "Pas de six ans. Point de six ans" ("Not six years. No six years"), drowning out the voice of the Governor. Peaceful protests continued until a resolution to abolish apprenticeship was passed and de facto freedom was achieved. This made Trinidad the first British colony with slaves to completely abolish slavery.[19] The successful resistance of the implementation of the full six-year term of the Apprenticeship system and Abolition of Slavery in Trinidad was marked by ex-slaves and free coloureds joining in celebrations thru the streets in what became known as their annual Canboulay celebrations. This event in Trinidad influenced full emancipation in the other British colonies which was legally granted two years ahead of schedule on 1 August 1838.

After Great Britain abolished slavery, it began to pressure other nations to do the same. France finally abolished slavery in 1848. By then Saint-Domingue had already won its independence and formed the independent Republic of Haiti. French-controlled islands were then limited to a few smaller islands in the Lesser Antilles.

See also

References

- ↑ "British Involvement in the Transatlantic Slave Trade". The Abolition Project. E2BN - East of England Broadband Network and MLA East of England. 2009. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ↑ Kitchin, Thomas (1778). The Present State of the West-Indies: Containing an Accurate Description of What Parts Are Possessed by the Several Powers in Europe. London: R. Baldwin. p. 21.

- ↑ Hilary Beckles and Verene Shepherd, eds. Caribbean slavery in the Atlantic world (2000).

- ↑ Kenneth Morgan, Slavery, Atlantic trade and the British economy, 1660-1800 (2000).

- ↑ Richard B. Sheridan (1974). Sugar and Slavery: An Economic History of the British West Indies, 1623-1775. Canoe Press. pp. 415–26.

- ↑ David A. G. Waddel, "Queen Anne's Government and the Slave Trade." Caribbean Quarterly 6.1 (1960): 7-10.

- ↑ Edward Gregg. Queen Anne (2001), pp. 341, 361.

- ↑ Hugh Thomas (1997). The Slave Trade: The Story of the Atlantic Slave Trade: 1440 - 1870. p. 236.

- ↑ Richard B. Sheridan, "Africa and the Caribbean in the Atlantic slave trade." American Historical Review 77.1 (1972): 15-35.

- ↑ Vinita Moch Ricks. Through the Lens of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-4835-1364-5.

- ↑ Herbert S. Klein and Ben Vinson III, eds., African slavery in Latin America and the Caribbean (2007).

- ↑ K. F. Kiple, The Caribbean Slave: A Biological History (1985).

- ↑ Keith Mason, "Demography, Disease and Medical Care in Caribbean Slave Societies." (1986): 109–119. DOI: 10.2307/3338787

- ↑ Kiple, The Caribbean Slave: A Biological History (1985).

- ↑ "French Revolutionary Wars Timeline: 1794". Emerson Kent. Emerson Kent. 2016. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

the first abolition ... revoked in 1802. The second, and final, abolition will be passed in 1848.

- ↑ "CHRONOLOGY-Who banned slavery when?". Reuters. Thomson Reuters. March 22, 2007. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ↑ Oldfield, Dr John (February 17, 2011). "British Anti-slavery". BBC History. BBC. Retrieved January 2, 2017.

- ↑

Dusenbury, Jonathan (October 10, 2016). "SLAVERY AND THE REVOLUTIONARY HISTORIES OF 1848". Age of Revolutions. Age of Revolutions. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

Enter Victor Schoelcher. After returning from Senegal in early March of 1848, the prominent abolitionist persuaded Arago to place him in charge of a commission to end slavery. On April 27, the commission drafted a decree of general and unconditional emancipation in the colonies.

- 1 2 Dryden, John (1992), "Pas de Six Ans!", In: Seven Slaves & Slavery: Trinidad 1777–1838, by Anthony de Verteuil, Port of Spain, pp. 371–379.

- ↑ "Slavery Abolition Act 1833". 28 August 1833. Archived from the original on 24 May 2008. Retrieved 4 June 2008.

- ↑ Oldfield, Dr John (February 17, 2011). "British Anti-slavery". BBC History. BBC. Retrieved January 2, 2017.

the new legislation called for the gradual abolition of slavery. Everyone over the age of six on August 1, 1834, when the law went into effect, was required to serve an apprenticeship of four years in the case of domestics and six years in the case of field hands

Bibliography

- Beckles, Hilary McD., and Andrew Downes. "The Economics of Transition to the Black Labor System in Barbados, 1630–1680," Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol. 18, No. 2 (Autumn 1987), pp. 225–247 in JSTOR

- Brown, Vincent. "The Reaper's Garden" (Harvard University Press, 2008)

- Bush, Barbara. "Hard Labor: Women, Childbirth, and Resistance in British Caribbean Slave Societies", in David Barry Gaspar and Darlene Clarke Hine, eds, More Than Chattel: Black Women and Slavery in the Americas (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996), pp. 193–217.

- Bush, Barbara. Slave Women in Caribbean society, 1650-1838 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990).

- Butler, Kathleen Mary. The Economics of Emancipation: Jamaica & Barbados, 1823–1843 (1995) online edition

- Dunn, Richard S., "The Barbados Census of 1680: Profile of the Richest Colony in English America," William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 26, no. 1 (January 1969), pp. 3–30. in JSTOR

- Giraldo, Alexander. Obeah: The Ultimate Resistance (2007)

- Miller, Joseph C., "The Way of Death: West Central Africa," (The University of Wisconsin Press, 1988)

- Molen, Patricia A. "Population and Social Patterns in Barbados in the Early Eighteenth Century," William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 28, No. 2 (April 1971), pp. 287–300 in JSTOR

- Morrissey, Marietta. Slave women in the New World (Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 1989).

- Ragatz, Lowell Joseph. "Absentee Landlordism in the British Caribbean, 1750-1833," Agricultural History, Vol. 5, No. 1 (January 1931), pp. 7–24 in JSTOR

- Reddock, Rhoda E. "Women and Slavery in the Caribbean: A Feminist Perspective", Latin American Perspectives, 12:1 (Winter 1985), 63–80.

- Sainvil, Talisha. Tradition and Women in Resistance (2007) Monday, November 26, 2007.

- Sheridan; Richard B. Sugar and Slavery: An Economic History of the British West Indies, 1623-1775 (University of the West Indies Press, 1994) online edition

- Smallwood, Stephanie. "Saltwater Slavery" (First Harvard University Press, 2008)

- Thomas, Robert Paul. "The Sugar Colonies of the Old Empire: Profit or Loss for Great Britain?" Economic History Review Vol. 21, No. 1 (April 1968), pp. 30–45 in JSTOR

External links

- Phillip, Nicole (2002). Producers, Reproducers, and Rebels: Grenadian Slave Women 1783-1833 - Conference paper published by the University of the West Indies.

- Watson, Karl (2001). Slavery and Economy in Barbados. In British History: Empire & Sea Power. The BBC, online series.

- Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice

- Archaeology, plantations and slavery in the French West Indies - Video by Manioc.

- Slave community foodways on a French colonial plantation : zooarchaeology at Habitation Crève Cœur, Martinique - Video by Manioc.

- Le cas particulier qui regarde les négresses : The Black Female Body in the Making of Eighteenth-Century French Subjectivity and Citizenship - Video by Manioc.

- Charles Auguste Bisette and The Police des Noirs in the French Atlantic - Video by Manioc.

- French Guiana, [s.l. ; s.n., 1919. Manioc

- Rodway, James. Guiana : British, Dutch and French, London, T. Fisher Unwin, 1912. Manioc

- Edwards, Bryan. An historical survey of the French colony in the island of St. Domingo : comprehending a short account of its ancient government, political state, population, productions, and exports ; a narrative of the calamities which have desolated the country ever since the year 1789, with some reflections on their causes and probable consequences : and a detail of the military transactions of the British army in that island to the end of 1794, London, John Stockdale, 1797. Manioc