Prostitutes in South Korea for the U.S. military

| Prostitutes in South Korea for the U.S. military | |||||||

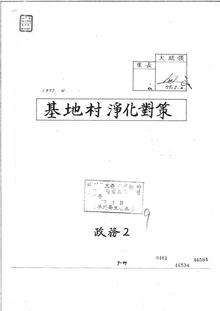

North Korean nurses captured by South Korean and US soldiers.[1] | |||||||

| Alternate Korean name | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hangul | 양공주[2] | ||||||

| Hanja | 洋公主 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Alternate Korean name | |||||||

| Hangul | 미군 위안부[3][4] | ||||||

| |||||||

During and following the Korean War, prostitutes in South Korea were frequently used by the U.S. military. Prostitutes servicing members of the U.S. military in South Korea have been known locally under a variety of terms. Yankee princess (Hangul: 양공주[5][6][7]—also translated as Western princess) is a common name and literal meaning for the prostitutes in the Gijichon, U.S. military Camp Towns[2][8][9] in South Korea.[10][11][12] Yankee whore (Hangul: 양갈보 Yanggalbo)[5] and Western whore are also common names. The women are also referred to as U.N. madams (Hangul: 유엔마담,[13][14] U.N. madam).[15] Juicy girls is a common name for Filipina prostitutes.[16] The term "Western princess" has been commonly used in the press, such as The Dong-a Ilbo for decades.[10] On the other hand, it is also used as an insulting epithet.[17]

Until the early 1990s, the term Wianbu (Hangul: 위안부, "Comfort Women") was often used by South Korean media and officials to refer to prostitutes for the U.S. military,[18][19] but comfort women was also the euphemism used for the sex slaves for the Imperial Japanese Army,[20][21][22] and in order to avoid confusions, the term yanggongju replaced wianbu to refer to sexual laborers for the U.S. military.[2][23][24] The early 1990s also saw the two women's rights movements diverge: on one side the one representing the Cheongsindae (Comfort women for the Japanese military), and on the other side the movement representing the Gijichon (Camptown for the US military), even if some women happen to have been victims of forced labor on both sides.[25] Now some South Korean media use the term migun wianbu (미군 위안부, 美軍慰安婦 "US military comfort women"),[3][4] literally American Comfort Women.

It is illegal for United States Forces Korea (USFK) service members to patronize prostitutes in Korea. Prostitution and the patronizing of a prostitute are crimes in the Republic of Korea (ROK) and are punishable under the USA's Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ).[26]

History

According to United States Forces Korea's policy, "Hiring prostitutes is incompatible with our military core values."[27] In the Allied-occupied Korea, between 1950 and 2007, the total number of women amounted to over one million in all South Korea.[2][8][28] Some women chose to become prostitutes.[29] Prostitutes for U.S. soldiers were esteemed to be at the bottom of the social hierarchy by South Koreans,[30] they were also lowest status within the hierarchy of prostitution.[31]

U.S. military and Syngman Rhee rule

In September 1945, United States Armed Forces occupied Korea, including Imperial Japanese comfort stations.[32] The women in comfort stations were also taken over.[8][32] In 1946, the United States Army Military Government in Korea outlawed prostitution in South Korea.[7][33]

Under US Military rule, Korean society treated prostitutes with humiliation that included stoning and cursing from children.[6] However, by 1953, the total number of prostitutes amounted to 350,000.[7][33] Between the 1950s and 1960s, 60 percent of South Korean prostitutes worked near U.S. military camps.[7][33] During the Korean War, it was the South Korean Army that controlled Wianbu units performing sexual services for United Nations and South Korean soldiers.[2][34] Throughout the Korean War, two separate types of comfort stations were operated.[35] One was U.N. Comfort Stations (UN위안소, UN慰安所) for UN peacekeeping units, and the other was Special Comfort Stations (특수위안소, 特殊慰安所) for soldiers of the Republic of Korea Army.[35] U.N. Comfort Stations were administered in collaboration with provincial governors, mayors and police.[36] The majority of women working in U.N. Comfort Stations were married and supporting their families.[36] On the front lines, women were brought in by trucks without permission.[2]

Second Republic (1960–1961)

The Second Republic viewed prostitution as something of a necessity.[37] In 1960, lawmakers of the National Assembly urged the South Korean government to train a supply of prostitutes for allied soldiers to prevent them from spending their dollars in Japan.[37] Lee Seung-u, the deputy home minister, gave a response to the National Assembly that the government had made some improvements in the "Supply of Prostitutes" for American soldiers.[37]

Military government rule

Park Chung-hee, who ruled South Korea during the 1960s and 1970s, and the father of the former president Park Geun-hye, encouraged the sex industry in order to generate revenue, particularly from the U.S. military.[40] Park seized power in the May 16 coup, and immediately enforced two core laws.[41] The first was the prostitution prevention law, which excluded "camp towns" from the governmental crackdown on prostitution; the second was the tourism promotion law, which designated camp towns as special tourism districts.[41]

During the 1960s, camp town prostitution and related businesses generated nearly 25 percent of the South Korean GNP.[42] In 1962, 20,000 comfort women were registered.[2] The prostitutes attended classes sponsored by their government in English and etiquette to help them sell more effectively.[43] They were praised as "dollar-earning patriots" or "true patriots" by the South Korean government.[29][40][43] In the 1970s one junior high school teacher told his students that "The prostitutes who sell their bodies to the U.S. military are true patriots. Their dollars earned greatly contributes to our national economy. Don't talk behind their back that they are western princesses or U.N. madams."[13]

In 1971, the number of American soldiers was reduced by 18,000, due to the Nixon Doctrine.[44][45] Because of this, South Koreans were more afraid of the North Korean threat and its economic impact.[46] Even so, camp town prostitution had already become an important component of South Korean livelihood.[46] The advocacy group My Sister's Place wrote in 1991 that the American soldiers contributed one billion dollars to the South Korean economy which was 1% of the South Korean GNP.[47]

Despite this, there were issues of venereal disease and racist conflict. U.S. military personnel advised the South Korean government that the camp towns were breeding grounds for sexually transmitted infections and places of racist discrimination.[48] The venereal disease ratio per 1,000 American soldiers rapidly increased, from 389 (in 1970), 553 (in 1971), and 692 (in 1972).[45]

Camp town clubs were separated for blacks and whites, and women were classified in accordance with the soldiers' race.[38] The residents near Camp Humphreys discriminated between African Americans and white Americans.[38] African American soldiers vented their anger against camp town residents.[38] On July 9, 1971, 50 African American soldiers provoked a riot against racist discrimination and destroyed some clubs near Camp Humphreys.[38] In turn, residents hunted down African American soldiers with sickles.[38] American military police and South Korean police quelled the rioters.[38]

In August 1971, the Secretary of Home Affairs Ministry, in cooperation with health authorities, gave orders to each police station to take precautions against sexually transmitted diseases and to instruct prostitutes about them.[44] On December 22, 1971, Park Chung-hee, the President of South Korea, enforced the Base Community Clean-Up Campaign.[38] The government educated women not to discriminate racially and banned clubs that posted segregationist signboards.[38]

The US Military Police Corps and South Korean officials regularly raided prostitutes who were thought to be spreading disease, and would detain those thought to be ill, locking them up under guard in so-called "monkey houses" that had barred windows,[43] and the women were forced to take medications that were reported to make them vomit.[43] Women who were certified to be without disease wore tags.[29] In the 1970s, U.S. military officials and South Korean bureaucrats discussed the matter of preventing epidemics and government efforts to register prostitutes and requiring them to carry medical certification.[37] The US military issued and required the prostitutes who worked at clubs to carry venereal disease cards, and also published a venereal disease guide to inform American soldiers patronizing bars.[49]

The South Korean government educated prostitutes who worked at the U.S. military camp in regard of preventing venereal disease. The South Korean bureaucrats educated that prostitution is an act of patriotism.[50] The bureaucrats informed the prostitutes of their contribution to the development and security of South Korea when they serve the U.S. soldiers with a healthy and clean body along with cooperative attitudes. The former Chief Secretary of the Blue House who directed the Base Community Clean-up Campaign, educated the prostitutes to learn the spirit of prostitutes who served the U.S. military during 1945 in Japan.[51] The former presidential secretary for audit and inspection, Hong Jong-chul, attempted to make policies for the prostitutes in base communities such as building apartments for them.[52]

There are reports that some women were killed by soldiers or committed suicide.[29]

Post-military government rule

During the early 1990s, the prostitutes became a symbol of South Korean anti-American nationalism.[53] In 1992, there were about 18,000 registered and 9,000 unregistered South Korean women around U.S. military bases.[54]

In 1992, Yun Geum-i, a camptown sex worker in Dongducheon, was brutally killed by U.S. servicemen.[55][56][57] Yun was found dead with a bottle stuffed into her vagina and an umbrella into her anus.[58] In August 1993, the U.S. government compensated the victim's family with about US$72,000.[59] However, the murder of a prostitute did not itself spark a national debate about the prerogatives of the U.S. forces; on the other hand, the rape of a twelve-year-old Okinawan school girl in 1995 by three American servicemen, one being a U.S. Navy Seaman, the others U.S. Marines elicited much public outrage and brought wider attention to military-related violence against women.[57]

Since the 2000s, the majority of prostitutes have been Philippine or Russian women; South Koreans have become less numerous.[10][60] there is also evidence of women from the Philippines, China, and Kyrgyzstan being subjected to forced prostitution near U.S. military bases.[61] Since the mid-1990s, foreigners make up 80–85 percent of the women working at clubs near military bases.[62]

On the other hand, South Korean prostitutes are still represented in large numbers. According to the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, South Korean prostitutes numbered about 330,000 in 2002.[63] Most of these are not working near US bases, but operating on the local economy. In 2013, the Ministry estimated that about 500,000 women worked in the national sex industry.[40] The Korean Feminist Association estimates the actual number may exceed one million. According to the estimates up to one-fifth of women between the ages of 15 and 29 have worked in the sex industry.[40]

The South Korean government also admits sex trade accounts for as much as 4 percent of the annual gross domestic product.[40] In August 1999, a Korean club owner in Dongducheon was accused of trafficking in women by bringing more than 1000 Philippine and Russian women into South Korea for U.S. military bases, but a South Korean judge overturned the warrant.[64] In 2000, five foreign women locked in a brothel died in a fire in Gunsan.[8]

In 2002, Fox Television reported casing brothels where trafficked women were allegedly forced to prostitute themselves to American soldiers.[64] U.S. soldiers testified that the club or bar owners buy the women at auctions, therefore the women must earn large sums of money to recover their passports and freedom.[8] In May 2002, U.S. lawmakers asked U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld for an investigation that "If U.S. soldiers are patrolling or frequenting these establishments, the military is in effect helping to line the pockets of human traffickers".[64]

In June 2002, the U.S. Department of Defense pledged to investigate the trafficking allegations.[64] In 2003, the Seoul District Court ruled that three night club owners near Camp Casey must compensate all Filipina women who had been forced into prostitution.[65] The club owners had taken their passports and had kept the women locked up.[66] One Philippine woman who was in captivity kept a diary about her confinement, beating, abortion and starvation.[67] Before the trial began, the International Organization for Migration studied the trafficking of foreign women and reported the result to its headquarters in Geneva.[67] The Philippine Embassy also joined the proceedings, making it the first embassy to take steps on behalf of its nationals.[65]

In 2002, the South Korean government completely discontinued issuing visas to Russian women, so prostitution businesses moved to bring in more Filipinas instead.[68][62] Human traffickers also brought in Russian women through sham marriages.[62] In 2005, Filipina and Russian women accounted for 90 percent of the prostitutes in U.S. military camp towns.[41] In 2005, Hwang Sook-hyang, a club owner in Dongducheon, was sentenced to a 10-month suspended sentence and 160 hours of community service on charges of illegal brothel-keeping.[69] The following civil trial sentenced him to compensate US$5,000 to a Philippine woman who was forced to have sex with U.S. soldiers between February 8 and March 3, 2004.[69] The Philippine woman was recruited by a South Korean company in the Philippines as a nightclub singer in 2004, then she and several Philippine women were locked inside Hwang's club and forced to have sex with U.S. soldiers.[69] The former "juicy bar" employees testified that soldiers usually paid US$150 to bring women from the bar to a hotel room for sex; the women received US$40.[70] Most juicy bars have a quota system linked to drink purchases.[70] Women who do not sell enough juice are forced into prostitution by their managers.[70]

In 2004, the U.S. Defense Department proposed anti-prostitution. A U.S. serviceman at Camp Foster (located on Okinawa) told a Stars and Stripes reporter that although prostitution was illegal in the United States, in South Korea, Thailand and Australia, it was "pretty open".[71] By 2009, the Philippine Embassy in South Korea had established a "Watch List" of bars where Philippine women were forced into prostitution and were considering sharing it with the U.S. military in hopes that U.S. commanders would put such establishments near bases off-limits to their troops.[72]

As of 2009, some 3,000 to 4,000 women working as prostitutes came annually from Southeast Asia, accounting for 90% of the prostitutes.[73] Despite prostitution being illegal in South Korea, camp towns were still practically exempted from crackdowns.[73]

In 2010, the United States Department of State, reported the predicament of women who worked at bars near U.S. military bases as one of ongoing human trafficking concerns in South Korea.[74] The Government of the Philippines stopped approving contracts that promoters used to bring Philippine women to South Korea to work near U.S. military bases.[75]

In 2011, the Eighth Army founded the Prevention of Sexual Assault Task Force; the task force assessed and reported the climate in South Korea regarding sexual assault among U.S. soldiers.[76]

In 2012, a United States Forces Korea public service announcement clarified, "Right now, young women are being lured to Korea thinking they will become singers and dancers," and "Instead, they will be sexually exploited in order to support their families." The United States Forces Korea posted a video on YouTube, clarifying that "buying overpriced drinks in a juicy bar supports the human trafficking industry, a form of modern-day slavery."[74] However, some U.S. commanders continue to allow American soldiers to patronize the bars as long as they have not been caught directly engaging in prostitution or human trafficking.[77] Most recently, in June 2013, General Jan-Marc Jouas placed all juicy bars outside Osan Air Base off-limits for Seventh Air Force personnel. This change in policy resulted in three weeks of large scale protests in the local area, however, General Jouas credits this change in policy as resulting in most Juicy bars in the area closing down.[78][79][80]

On June 25, 2014 122 surviving Korean comfort women for the U.S. forces filed a lawsuit against their government to reclaim human dignity and demand ₩10 million compensation per plaintiff. According to the claim, they were supervised by the U.S. forces and the South Korean government and South Korean authorities colluded with pimps in blocking them from leaving.[81][82][83] In 2017, a three judge panel of the Central District Court in Seoul, ordered the government to pay 57 plaintiffs the equivalent of $4,240 each in compensation for physical and psychological damage.[84]

Since 2014, USFK has banned all USA military service members from visiting any establishments that allow patrons to buy drinks (or juice) for the hostesses for the purposes of their companionship.[85] Hostess bars, juicy bars and anywhere that the company of female can be purchased are off-limits to American military. Since US military service members were a large source of the hostess bars clientele, this effectively closed all hostessing themed establishments nearby all US military bases in Korea.

Women and offspring

The children born to American soldiers and South Korean prostitutes were often abandoned when soldiers returned to the U.S.[17] By the 1970s, tens of thousands of children had been born to South Korean women and American soldiers.[60] In South Korea, these children are often the target of racist vitriol and abuse, being called "western princess bastards" (Yanggongju-ssaekki), "darkies", or "niggers" (Kkamdungi).[5] It was difficult for South Korean prostitutes around the U.S. military bases to escape from being stigmatized by their society, thus their only hope was to move to the United States and marry an American soldier.[8] Trafficked Filipinas also had the same expectation.

Some American soldiers paid off the women's debt to their owners to free them in order to marry them.[8] However, most U.S. soldiers are unaware of the trafficking. Some soldiers have helped Philippine women escape from clubs.[64] In 2009, juicy bar owners near Camp Casey who had political muscle, demanded that U.S. military officials do something to prevent G.I.s from wooing away their bar girls with promises of marriage.[70] In June 2010, U.S. forces started a program to search for soldiers who had left and abandoned a wife or children.[10] Haunting the Korean Diaspora: Shame, Secrecy, and the Forgotten War, a research of prostitutes by Grace M. Cho who was the daughter of a G.I. and a South Korean woman, was awarded the best 2010 book on Asia and Asian America by the American Sociological Association.[86][87]

A former South Korean prostitute said to The New York Times that they have been the biggest sacrifice of the Mutual Defense Treaty Between the United States and the Republic of Korea.[37] The women also see themselves as war victims.[42] They are seeking compensation and apologies.[43] Because of this tainted history, the primary stereotype that most South Koreans held of South Korean women who had copulated with white men or "crackers" ("Hindungi") was mainly negative.[17] Besides, the first transnational marriages were mostly between U.S. soldiers and Korean women who worked in U.S. military bases or who were camp prostitutes.[88] By 2010, more than 100,000 Korean women had married U.S. soldiers and moved to the United States.[86][87] South Korean women married to foreigners are often viewed as prostitutes.[31] Marriages between South Koreans and foreigners often carry a serious stigma in South Korean society.[88] A woman who is married to a Spaniard, said that almost 100% of middle-aged South Korean men look her up and down when she walks hand in hand with her husband.[89]

In popular culture

Films

The Evil Night (1952) and A Flower in Hell (1958) by Shin Sang-ok depict South Korean prostitutes.[90][91] Silver Stallion (1991) by Chang Kil-su depicts one prostitute symbolizing the raped nation of Korea.[30] Spring in My Hometown (1998) by Lee Kwang-mo depicts one prostitute waiting for her American lover who never returns.[30] Address Unknown by Kim Ki-duk depicts the lover of a prostitute who never returns to South Korea.[30] The VR Film "Bloodless" (2017) by Gina Kim is based on the true story of a South Korean prostitute,Yun Keum Yi, brutally murdered by a US soldier in 1992.[92]

Theater

The play Seven Neighborhoods Like Warm Sisters depicts prostitutes living near Camp Humphreys.[93][94]

Novels

Song Byung-soo depicts prostitutes in Shorty Kim (1957).[30] A Stray Bullet by Yu Hyun-mok depicts one woman who becomes a prostitute to rescue her family.[30] Lee Moon-yul is depicted in What Crashes, Has Wings (1988).[30]

Documentaries

Camp Arirang is a 1995 documentary that claims one million females had been involved in prostitution up until 1995.

Controversy over the name of US Prostitutes in South Korea

Until the early 1990s, the term Prostitutes (comfort women) was used to include people who were prostitutes to soldiers. Today, there is a debate about whether it is appropriate to express comfort women as comfort women by saying comfort women as a means of forced mobilization to the state.[95]

See also

References

- ↑ 한국군 '특수위안대'는 사실상의 공창 창간 2주년 기념 발굴특종 한국군도 '위안부' 운용했다. Ohmynews (in Korean). 2002-02-26. Retrieved 2014-03-05.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Rhee, Young-hoon (2009-06-01). "그날 나는 왜 그렇게 말하였던가". New Daily. Retrieved 2013-04-07.

- 1 2 “박정희 정부, ‘미군 위안부·기지촌 여성’ 직접 관리” 뉴시스 2013.11.06

- 1 2 유승희 의원 "박정희 정권 '미군 위안부' 관리" 경향신문 2013-11-06

- 1 2 3 Cheng, Sealing (2010). On the Move for Love: Migrant Entertainers and the U.S. Military in South Korea. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-8122-4217-1.

- 1 2 Höhn, Maria (2010). Over There: Living with the U.S. Military Empire from World War Two to the Present. Duke University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-8223-4827-6.

- 1 2 3 4 Cho, Grace (2008). Haunting the Korean Diaspora: Shame, Secrecy, and the Forgotten War. University of Minnesota Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-8166-5275-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hughes, Donna; Chon, Katherine; Ellerman, Ellerman. "Modern-Day Comfort Women:The U.S. Military, Transnational Crime, and the Trafficking of Women" (PDF). University of Rhode Island. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-28. Retrieved 2013-05-26.

- ↑ "The United States, South Korea, and "Comfort Women"". Stanford University. January 22, 2009. Retrieved 2013-05-26.

- 1 2 3 4 "[뉴스테이션/탐사리포트]또 다른 양공주의 비극". The Dong-a Ilbo. 2010-04-27. Retrieved 2013-04-08.

- ↑ "[백년명가②] "88년부터 찌개로… 김치 넣기 시작했지"". JoongAng Ilbo. 2009-06-24. Archived from the original on 2013-06-19. Retrieved 2013-04-07.

- ↑ Clough, Patricia (2007). The Affective Turn: Theorizing the Social. Duke University Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-8223-3925-0.

- 1 2 "[늘보의 옛날신문읽기] 양공주, 유엔마담 그리고 화냥년". The Dong-a Ilbo. 2000-11-03. Retrieved 2013-04-08.

- ↑ Pyo, Jeong-hun (2008-08-23). "[추억 엽서-대한민국 60년] <35> 양공주". The Chosun Ilbo. Archived from the original on 2013-06-22. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- ↑ Seoul Journal of Korean Studies, Volume 14. Seoul National University. 2001. p. 269.

- ↑ Rabiroff, Jon (August 17, 2010). "Hostess shortage leaves 'juicy bars' pondering future". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 2013-05-16.

- 1 2 3 Sung So-young (2012-06-13). "The actual reality of interracial relationships". Joongang Daily. Archived from the original on 2013-03-21. Retrieved 2013-04-07.

- ↑ Gi, Wook Shin (2006). Rethinking Historical Injustice and Reconciliation in Northeast Asia: The Korean Experience. Routledge. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-415-47451-1.

- ↑ "UN軍 相對 慰安婦 13日부터 登錄實施". The Dong-a Ilbo. 1961-09-14. Retrieved 2013-05-01.

- ↑ The Asian Women's Fund. "Who were the Comfort Women?-The Establishment of Comfort Stations". Digital Museum The Comfort Women Issue and the Asian Women's Fund. The Asian Women's Fund. Archived from the original on August 7, 2014. Retrieved August 8, 2014.

- ↑ The Asian Women's Fund. "Hall I: Japanese Military and Comfort Women". Digital Museum The Comfort Women Issue and the Asian Women's Fund. The Asian Women's Fund. Archived from the original on March 15, 2013. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

The so-called 'wartime comfort women' were those who were taken to former Japanese military installations, such as comfort stations, for a certain period during wartime in the past and forced to provide sexual services to officers and soldiers.

- ↑ Argibay, Carmen (2003). "Sexual Slavery and the Comfort Women of World War II". Berkeley Journal of International Law.

- ↑ Clough, Patricia (2007). The Affective Turn: Theorizing the Social. Duke University Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-8223-3925-0.

Wianbu, the word used to refer to the so-called comfort women who were forced sexual laborers for the Japanese military, was also used to describe the women who were sexual laborers for the U.S. military. That is, until another word replaced wianbu in order to connote a different kind of shame. Yanggongju would draw the line between the violated virgins and the willing whores. Yanggongju, literally meaning 'western princess' and commonly translated as 'Yankee whore' replaced wianbu as the popular name for women who are prostitutes for the U.S. military.

- ↑ "한국군도 '위안부' 운용했다". OhmyNews. Archived from the original on 2012-11-07. Retrieved 2014-06-10.

- ↑ Cho, Grace (2008). Haunting the Korean Diaspora: Shame, Secrecy, and the Forgotten War. University of Minnesota Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-8166-5275-4.

- ↑ SCAPARROTTI, Curtis (15 October 2014). "United States Forces Korea (USFK) Command Policy Letter #12, Combating Prostitution and Trafficking in Persons" (PDF). Combating Prostitution in Korea. USFK Korea. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- ↑ Zakaria, Tabassum (2013-04-29). "U.S. military faces scrutiny over its prostitution policies". Reuters. Retrieved 2013-05-14.

- ↑ Lee, Jin-kyung (2010). Service Economies: Militarism, Sex Work, and Migrant Labor in South Korea. University of Minnesota Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-8166-5126-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Lee, Min-a (2005-07-31). "Openly revealing a secret life". JoongAng Ilbo. Archived from the original on 2013-06-19. Retrieved 2013-04-07.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hyunseon Lee. "Broken Silence: The Taboo of Korean Prostitutes during American Occupation and Its Depiction in the Korean Films of the 1990s" (PDF). University of London. Retrieved 2013-04-18.

- 1 2 Kim, Elaine (1997). Dangerous Women: Gender and Korean Nationalism. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-91506-9.

- 1 2 Cho, Grace (2008). Haunting the Korean Diaspora: Shame, Secrecy, and the Forgotten War. University of Minnesota Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-8166-5275-4.

- 1 2 3 Clough, Patricia (2007). The Affective Turn: Theorizing the Social. Duke University Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-8223-3925-0.

- ↑ "한국군 '특수위안대'는 사실상의 공창". OhmyNews. 2002-02-26. Retrieved 2013-04-12.

- 1 2 Höhn, Maria (2010). Over There: Living with the U.S. Military Empire from World War Two to the Present. Duke University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-8223-4827-6.

- 1 2 Höhn, Maria (2010). Over There: Living with the U.S. Military Empire from World War Two to the Present. Duke University Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-8223-4827-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Choe, Sang-hun (2009-01-07). "Ex-Prostitutes Say South Korea and U.S. Enabled Sex Trade Near Bases (page 2)". New York Times. Retrieved 2013-04-07.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "'한-미 우호'의 아랫도리… '양공주'들을 민간외교관으로 활용하다". Hankyoreh. 2005-02-01. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- ↑ "'박정희 리스트'로 고구마 캐듯 수사김창룡이 '구명'제안, 백선엽이 결심". OhmyNews. 2004-08-10. Retrieved 2013-05-22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ghosh, Palash (2013-04-29). "South Korea: A Thriving Sex Industry In A Powerful, Wealthy Super-State". International Business Times. Retrieved 2013-05-15.

- 1 2 3 Lee, Jin-kyung (2010). Service Economies: Militarism, Sex Work, and Migrant Labor in South Korea. University of Minnesota Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-8166-5126-9.

- 1 2 Park, Soo-mee (2008-10-30). "Former sex workers in fight for compensation". Joongang Daily. Archived from the original on 2013-04-30. Retrieved 2013-04-07.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Choe, Sang-hun (2009-01-07). "Ex-Prostitutes Say South Korea and U.S. Enabled Sex Trade Near Bases". New York Times. Retrieved 2013-04-07.

- 1 2 Kim, Tae (2011-11-28). "대한민국 정부가 포주였다 [2011.11.28 제887호] [표지이야기] 성매매 단속하는 척하며 여성을 외화벌이 수단으로 여겼던 한국 정부… 한국전쟁 때 위안소 설치하고, 독재정권은 주한미군·일본인 대상 성매매 조장해". Hankyoreh. Retrieved 2013-04-07.

- 1 2 "유신공주는 양공주 문제엔 관심이 없었다". The Hankyoreh. 2012-11-30. Retrieved 2013-04-07.

- 1 2 Höhn, Maria (2010). Over There: Living With the U.S. Military Empire from World War Two to the Present. Duke University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-8223-4827-6.

- ↑ Moon, Katharine H.S (1997). Sex Among Allies. Columbia University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-231-10643-6. Quoting the newsletter of My Sister's Place, July 1991, p. 8.

- ↑ Cho, Grace (2008). Haunting the Korean Diaspora: Shame, Secrecy, and the Forgotten War. University of Minnesota Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-8166-5275-4.

- ↑ Kuo, Lenore (2005). Prostitution Policy: Revolutionizing Practice through a Gendered Perspective. New York University Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-8147-4791-9.

- ↑ Rowland, Ashley (December 19, 2014). "Attorney: Korean government encouraged prostitutes to service US troops - News - Stripes". Stripes. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ↑ Moon, Katharine H.S (1997). Sex Among Allies. Columbia University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-231-10643-6.

- ↑ Kim, Jeong-ja (2013). The Hidden Truth of the U.S. Military Comfort Women. Hanul Academy. p. 170. ISBN 978-89-460-5556-8. Archived from the original on September 30, 2013.

- ↑ Cho, Grace (2008). Haunting the Korean Diaspora: Shame, Secrecy, and the Forgotten War. University of Minnesota Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-8166-5275-4.

- ↑ Enriquez, Jean (November 1999). "Filipinas in Prostitution around U.S. Military Bases in Korea: A Recurring Nightmare". Coalition Against Trafficking in Women Asia Pacific. Retrieved 2013-05-25.

- ↑ Cho, Grace M. (2008). Haunting the Korean Diaspora: Shame, Secrecy, and the Forgotten War. University of Minnesota Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0816652747.

In October 1992, a camptown sex worker named Yun Geum-I was brutally murdered by one of her clients during a dispute.

- ↑ Moon, Gwang-lip (2011-09-30). "After soldier held for rape, U.S. vows assistance". JoongAng Ilbo. Archived from the original on 2013-06-19. Retrieved 2013-04-12.

- 1 2 Moon, Katharine. "Military Prostitution and the U.S. Military in Asia". The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus. Retrieved 2013-05-02.

- ↑ McHugh, Kathleen (2005). South Korean Golden Age Melodrama: Gender, Genre, And National Cinema. Wayne State University Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-8143-3253-5.

- ↑ "U.S. soldier free after brutal 1992 murder". The Hankyoreh. 2006-10-28. Retrieved 2013-04-15.

- 1 2 "6·25의 사생아 '양공주' 통곡 50년 전쟁 그리고 약소국의 아픈 상처 '양공주'. 6·25가 끝난 지 50년이나 흘렀지만, 분단과 전쟁의 희생양인 양공주는 아직도 민족사 한가운데에서 총성 없는 전쟁을 치르고 있다". 시사저널. 2003-07-29. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- ↑ "Republic of Korea 2017 Trafficking in Persons Report". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- 1 2 3 "[Editorial] Human trafficking in S. Korea". The Hankyoreh. 2009-02-28. Retrieved 2013-04-14.

- ↑ Moon, Kyung-ran (2004-09-02). "New figures on sex trade anger Seoul". Joongang Daily. Archived from the original on 2013-06-19. Retrieved 2013-04-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Macintyre, Donald (2002-08-05). "Base Instincts". Time. Retrieved 2013-04-23.

- 1 2 "Court rules in favor of Filipina prostitutes". JoongAng Ilbo. 2003-05-31. Archived from the original on 2013-06-19. Retrieved 2013-04-12.

- ↑ Kim, Seung-hyun (2002-10-17). "11 Filipinas sue owners of club". Joongang Daily. Archived from the original on 2013-06-19. Retrieved 2013-04-12.

- 1 2 "[EDITORIALS]Deliver them from 'hell'". Joongang Daily. 2002-10-19. Archived from the original on 2013-06-13. Retrieved 2013-04-08.

- ↑ "Filipinas forced into prostitution on the rise in S.Korea". The Hankyoreh. 2009-12-01. Retrieved 2013-04-08.

- 1 2 3 Robson, Seth (August 6, 2005). "Ex-bar worker who was forced into prostitution wins $5,000 judgment". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 2013-05-16.

- 1 2 3 4 Rabiroff, Jon (September 9, 2009). "'Juicy bars' said to be havens for prostitution aimed at U.S. military". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 2013-05-15.

- ↑ Allen, David (September 25, 2004). "Troops mixed on anti-prostitution proposal". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 2013-05-17.

- ↑ Rabiroff, Jon (September 26, 2009). "Philippine Embassy has 'watch list' of suspect bars in South Korea". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 2013-05-15.

- 1 2 Dujisin, Zoltán (Jul 7, 2009). "RIGHTS-SOUTH KOREA: Prostitution Thrives with U.S. Military Presence". Inter Press Service. Retrieved 2013-05-15.

- 1 2 "US servicemen in Korea contribute to human trafficking: report". Press TV. Dec 21, 2012. Archived from the original on 2013-03-04. Retrieved 2013-05-14.

- ↑ Rabiroff, Jon (June 18, 2010). "Report on human trafficking cites South Korean juicy bars". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 2013-05-15.

- ↑ Rowland, Ashley (May 21, 2013). "Report underscores Army's ineffectiveness to prevent sexual assaults in Korea". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 2013-05-21.

- ↑ Rabiroff, Jon (December 20, 2012). "USFK video links 'juicy bars' with human trafficking". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 2013-05-16.

- ↑ "Businesses counter-protest 'juicy bars' demo outside Osan". Stars and Stripes.

- ↑ "Bar owners, workers protest Osan's off-limits ban on juicy bars". Stars and Stripes.

- ↑ "Commentary - Fighting human trafficking - the Songtan Protest and its aftermath". af.mil. Archived from the original on 2013-12-15.

- ↑ "Claims South Korea Provided Sex Slaves for U.S. Troops Go to Court". The Wall Street Journal. Jul 15, 2014. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014.

- ↑ Ju-Min Park (11 July 2014). "Former Korean 'comfort women' for U.S. troops sue own government". Reuters. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014.

- ↑ "Former Korean 'comfort women' for U.S. troops sue own government". Yahoo News. 11 July 2014.

- ↑ "South Korea Illegally Held Prostitutes Who Catered to G.I.s Decades Ago, Court Says". The New York Times. January 20, 2017.

- ↑ "USFK bans buying drinks for 'juicy bar' workers". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- 1 2 Cohen, Joel (June 28, 2010). "Cho Wins Best Book on Asia Award". College of Staten Island. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- 1 2 "Fresh Ink". Brown Alumni Magazine. January–February 2011. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- 1 2 Kim, Soe-jung (2005-10-23). "Forum tackles overseas marriages". JoongAng Daily. Archived from the original on 2013-06-19. Retrieved 2013-04-12.

- ↑ Gwon, Seok-cheon (2012-03-14). "[권석천의 시시각각] 내 마음속 제노포비아". JoongAng Ilbo. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 2013-04-27.

- ↑ Cho, Grace (2008). Haunting the Korean Diaspora: Shame, Secrecy, and the Forgotten War. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 104–105. ISBN 978-0-8166-5275-4.

- ↑ Cho, Inēs (2002-01-18). "The Reel Story". Joongang Daily. Archived from the original on 2013-06-19. Retrieved 2013-04-12.

- ↑ "Films". Gina Kim.

- ↑ Moon, Gwang-lip (2013-04-12). "A tantalizing season for theatergoers has arrived". Joongang Daily. Archived from the original on 2013-06-19. Retrieved 2013-04-12.

- ↑ Moon, Haewon (2013-04-13). "감추고픈 기지촌의 역사 <일곱집매>". Joongang Ilbo. Archived from the original on 2013-06-19. Retrieved 2013-04-27.

- ↑ "유승희 "박정희 시절'미군위안부'관리, 대통령 친필 결재 서류 존재"" [Yoo Seung-hee "When Park Chung Hee was in charge of" US military comfort women "]. news.naver.com (in Korean). 6 November 2013. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Comfort women of South Korea. |

- Combating Trafficking in Persons (CTIP)

- Human Trafficking public service announcement on YouTube, United States Forces Korea Nov 20, 2012

- Women outside: Korean women and US Military on YouTube

- Comfort Women: Do you hear their cry? on YouTube

- This could now say: Sex alliance-cleansing exercise camptowns on YouTube (in Korean)

- Olsen, Harald (June 25, 2013). "10,000 Korean Children Born to Filipina Prostitutes". Korea Bang.