Aztec slavery

Aztec slavery, within the structure of the Mexica society, produced many slaves, known by the Nahuatl word, tlacotin. Within Mexica society, slaves constituted an important class.

Description

Slavery was not a station one was born into, but a state entered into as a form of punishment, out of financial desperation, or as a captive.[1] The practice consisted of two systems:

- Slavery, in the strictest sense of the term

- indentured servitude.

Aztecs as slaveowners

Slaveowners were required to provide food and shelter for their slaves.[1]

Women slave owners exerted much in the way of choice, in regard to slaves. For example, if a woman was widowed, it was not uncommon for her to either remarry one of her husband's slaves, or make one one of his slaves her personal steward.[1] The richest merchants in Mexica society were slave traders. Not only were they wealthy, but they were also granted special privileges. They were also considered to be very religious, and played a key role in the festival of Panquetzaliztli festival, in honor of Mexica god, Huitzilopochtli.[1]

Any person not related to a slave's master could be enslaved for trying to prevent a slave's escape. If one slave was not behave in accordance, he could be sentenced to death.[2]

Slaves in the Aztec society

While slavery could not be inherited, in Mexica society, one could, in fact, live indefinitely as a slave. For example, Moctezuma II, in addition to confiscating property, would condemn traitors, or their families, to slavery for life. He would also do the same to astrologers who failed to predict the occurrence of omens.[1]

Slaves were bound to their master's lands, until one's debt was paid to his master. Barring being a captive, being punished for committing a crime, or failing to pay an outstanding gambling debt, slavery was an institution one could enter into freely.[1][3] In that respect, the system was not slavery, but contractual indentured servitude, resulting in "unfree labor. However, it was such a widely held practice that the Mexica would often sell their children into slavery.[1]

Slaves wore maguey garments called "cueitl," which was a skirt that wrapped around the hips, one end overlapping the other, held together by a belt-like strap. Reflecting their low status in society, the cueitl of slaves were colorlessness.[1] Typically, upon the death of their owner, slaves who had performed outstanding services were freed, while the rest were passed on as part of the inheritance. As for assigned work, many slaves were sent to the regions of Cimatan and the Acalan, aquatic environments, to work as rowers and as laborers in the cacao groves, which was work that needed to be done year-round.[1]

Slaves were free to marry and make other person decisions. They were also expected to contribute to the betterment of Mexica society. For example, slaves helped move the military's equipment when it set off for battle.[1]

Slavery of war captives

Slavery was most difficult for war captives who, after being captured, could be sold.[1] In addition, they could also be sacrificed at a religious ceremony or festival.[1] For example, slaves were selected to be ixiptla, which is a representation of an god. They believed that the god would, in turn, represent a force of celestial natures such as the wind or the moon, and that through by sacrificing the slave, it would satisfy the god, who would then bring good fortune to the people.[1] And, in the event of a nobleman's death, slaves could be killed, and buried with him, to assist him in the underworld, as they assisted him in life.[1] The body parts of sacrificed slaves could be taken home and eaten with maize and salt as an extension of their sacrifice.[1]

Emancipation

A way for slaves to get their freedom was by running outside the walls, at the marketplace and stepping on a piece of human excrement, then presenting their case to the judges, asking for freedom.[2] If granted, the slaves would then be washed, given new clothes (not owned by the master), and declared free.

Aztec slave trade

Slaves were also frequent faces in the market of Tenochtitlan where they could be sold along with food, cloth, and handmade goods. However, the cities with the most well-known slave markets were Azcapotzalco and Itzocan.[1]

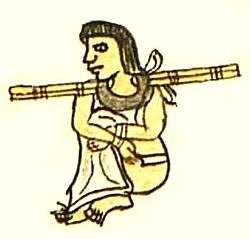

Usually, only wealthy men, or nobles, could often afford slaves. Slaves could be bought for 30 cotton garments called "quachtli." Slaves who could entertain their masters with a talent, such as by singing or dancing, were more expensive, and could cost upwards of 25 percent more.[1]

Collared slaves

Orozco y Berra reports that a master could not sell a slave without the slave's consent, unless the slave had been classified as incorrigible by an authority. Incorrigibility could be determined on the basis of repeated laziness, attempts to run away, or general bad conduct. Incorrigible slaves were made to wear a wooden collar, affixed by rings at the back. The collar was not merely a symbol of bad conduct: it was designed to make it harder to run away through a crowd or through narrow spaces.

When buying a collared slave, one was informed of how many times that slave had been sold. A slave who was sold three times as incorrigible could be sold to be sacrificed; those slaves commanded a premium in price. However, if a collared slave managed to present him- or herself in the royal palace or in a temple, he or she would regain liberty.

Voluntary slavery

Some slaves gave up their freedom to pay off gambling debts.[3] However, becoming a slave was a process. First, the gambler had to stand before four respected elders. They would then conduct a ceremony whereby the gambler would prefers his want (or need) to become a slave and be given, by his new owner, the price of his freedom, which was often 20 pieces of cloth and the means to live alone for a year before he began his slavery. After the gambler spent that amount, his service would be exchanged for food, shelter and clothing. Anyone could be a slave, though commoners were more likely to enter slavery voluntarily. But, because slaves were looked down upon, it was usually the last option one took to pay off a debt.[1] Beside gamblers, selling oneself into slavery was often a fate for aging courtesans or prostitutes, known among the Mexica as "ahuini".

Superstitions and slavery

It was believed that those who were born in the 13-day series, starting with 1 Ocelotl, were destined to be slaves, or that their lives would be burdened with something else undesirable.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Agurilar-Moreno, Manuel (2006). Handbook to Life in the Aztec World. California State University, Los Angeles.

- 1 2 Manuel Orozco y Berra (1816). La Civilización Azteca. Cien de México.

- 1 2 Smith, Dr. Michael E. (2006). Aztec Culture. Arizona State University.

- Thomas Ward “Expanding Ethnicity in Sixteenth-Century Anahuac: Ideologies of Ethnicity and Gender in the Nation-Building Process.” MLN 116.2 (March 2001): 419-452.