Pienza

| Pienza | |

|---|---|

| Comune | |

| Comune di Pienza | |

| |

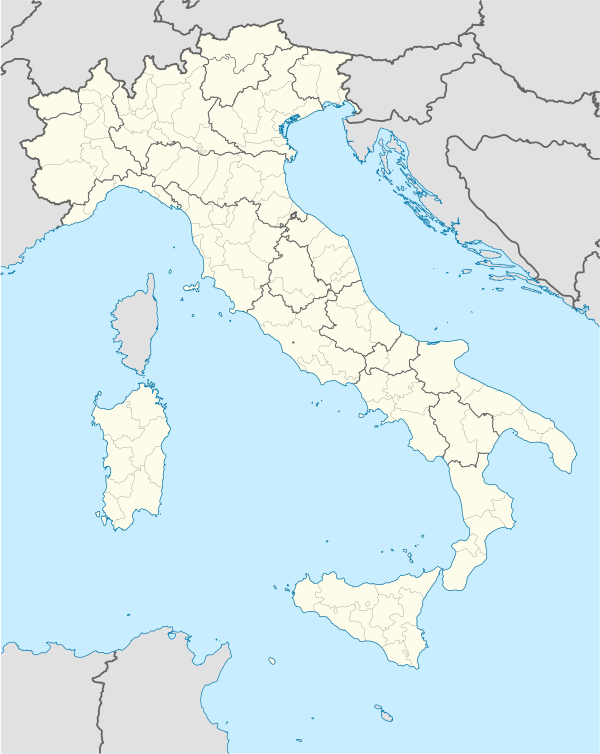

Pienza Location of Pienza in Italy | |

| Coordinates: 43°04′43″N 11°40′44″E / 43.07861°N 11.67889°E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Tuscany |

| Province | Siena (SI) |

| Frazioni | Cosona, La Foce, Monticchiello, Palazzo Massaini, Spadaletto |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Fabrizio Fè |

| Area | |

| • Total | 122.96 km2 (47.48 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 491 m (1,611 ft) |

| Population (28 February 2017) | |

| • Total | 2,091 |

| • Density | 17/km2 (44/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Pientini |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 53026 |

| Dialing code | 0578 |

| Patron saint | St. Andrew the Apostle |

| Saint day | November 30 |

| Website | Official website |

| UNESCO World Heritage site | |

| Official name | Historic Centre of the City of Pienza |

| Criteria | Cultural: (i)(ii)(iv) |

| Reference | 789 |

| Inscription | 1996 (20th Session) |

| Area | 4.41 ha (10.9 acres) |

Pienza, a town and comune in the province of Siena, in the Val d'Orcia in Tuscany (central Italy), between the towns of Montepulciano and Montalcino, is the "touchstone of Renaissance urbanism."[1]

In 1996, UNESCO declared the town a World Heritage Site, and in 2004 the entire valley, the Val d'Orcia, was included on the list of UNESCO's World Cultural Landscapes.

History

Before the village was renamed to Pienza its name was Corsignano. It is first mentioned in documents from the 9th century. Around 1300 parts of the village became property of the Piccolomini family.[2] after Enghelberto d'Ugo Piccolomini had been enfeoffed with the fief of Montertari in Val d'Orcia by the emperor Frederick II in 1220.[3] In the 13th century Franciscans settled down in Corsignano.[2]

In 1405 Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini (Italian: Enea Silvio Piccolomini) was born in Corsignano, a Renaissance humanist born into an exiled Sienese family, who later became Pope Pius II. Once he became Pope, Piccolomini had the entire village rebuilt as an ideal Renaissance town and renamed it after himself to Pienza which mean "city of Pius".[4] Intended as a retreat from Rome, it represents the first application of humanist urban planning concepts, creating an impetus for planning that was adopted in other Italian towns and cities and eventually spread to other European centers.

The rebuilding was done by Florentine architect Bernardo Gambarelli (known as Bernardo Rossellino) who may have worked with the humanist and architect Leon Battista Alberti, though there are no documents to prove it for sure. Alberti was in the employ of the Papal Curia at the time and served as an advisor to Pius. Construction started about 1459. Pope Pius II consecrated the Duomo on August 29, 1462, during his long summer visit. He included a detailed description of the structures in his Commentaries, written during the last two years of his life.

Main sights

Palazzo Piccolomini

The trapezoidal piazza is defined by four buildings. The principal residence, Palazzo Piccolomini, is on the west side. It has three stories, articulated by pilasters and entablature courses, with a twin-lighted cross window set within each bay. This structure is similar to Alberti's Palazzo Rucellai in Florence and other later palaces. Noteworthy is the internal court of the palazzo. The back of the palace, to the south, is defined by loggia on all three floors that overlook an enclosed Italian Renaissance garden with Giardino all'italiana era modifications, and views into the distant landscape of the Val d'Orcia and Pope Pius's beloved Mount Amiata beyond. Below this garden is a vaulted stable that had stalls for 100 horses.

The Duomo

The Duomo (Cathedral), which dominates the center of the piazza, has a facade that is one of the earliest designed in the Renaissance manner. Though the tripartite division is conventional, the use of pilasters and of columns, standing on high dados and linked by arches, was novel for the time. The bell tower, however, has a Germanic flavor as is the layout of the Hallenkirche plan, a "triple-nave" plan where the side aisles are almost as tall as the nave; Pius, before he became pope, served many years in Germany and praised the effects of light admitted into the German hall churches in his Commentari.[5] Works of art in the duomo include five altar paintings from the Sienese School, by Sano di Pietro, Matteo di Giovanni, Vecchietta and Giovanni di Paolo. The Baptistry, dedicated as usual to San Giovanni, is located next to the apse of the church.

Palazzo Vescovile

Pius encouraged cardinals to build palazzi to complete the city. Palazzo Vescovile, on the third side of the piazza, was built to house the bishops who would travel to Pienza to attend the pope. Its construction was financed by Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia (the future Pope Alexander VI but, at the time, Vatican Vice-Chancellor). It may represent a remodeling of the old town hall of Corsignano. It is now home to the Diocesan Museum,[6] and the Museo della Cattedrale. The collection includes local textile work as well as religious artifacts. Paintings include a 12th-century painted crucifix from the Abbey of San Pietro in Vollore, 14th century works by Pietro Lorenzetti (Madonna with Child) and Bartolo di Fredi (Madonna della Misericordia). There are also important works from the 14th and 15th centuries, including a Madonna attributed to Luca Signorelli.

Palazzo Comunale

Across from the church is the town hall, or Palazzo Comunale. When Corsigniano was given the status of an official city, a Palazzo was required that would be in keeping with the "city's" new urban position, though it was certainly more for show than anything else. It has a three-arched loggia on the ground floor facing the Cathedral and above it is the council chamber. It also has a brick bell tower that is shorter than its counterpart at the cathedral, to symbolize the superior power of the church. The set-back addition to the tower dates from 1599. It is likely that Bernardo Rossellino designed the Palazzo Comunale to be a free standing civic mediator between the religious space before the cathedral and secular market square to its rear.

The travertine well in the Piazza carries the Piccolomini family crest, and was widely copied in Tuscany during the following century. The well-head resembles a fluted, shallow Etruscan Bowl. The flanking Corinthian support a classical entablature columns whose decorations are clearly based upon actual source materials.

Other buildings

Other buildings in Pienza dating from the era of Pius II include the Ammannati Palace, named for Cardinal Jacopo Piccolomini-Ammannati, a "curial row" of three palaces (the Palazzo Jouffroy or Atrebatense belonging to Cardinal Jean Jouffroy, the Palazzo Buonconti, belonging to Vatican Treasurer Giliforte dei Buonconti, and the Palazzo Lolli constructed by apostolic secretary and papal relative Gregorio Lolli) arranged along the street behind the Bishops Palace. In the northeastern corner of Pienza is a series of twelve row houses constructed at the orders of the pope by the Sienese building contractor Pietro Paolo da Porrina.

About fifty meters west of the Cathedral Piazza is the church of San Francesco, with a gabled facade and Gothic portal. Among the buildings that survived from the old Corsignano, it is built on a pre-existing church that dated from the 8th century. The interior contains frescoes depicting the life of Saint Francis, those on the walls having been painted by Cristofano di Bindoccio and Meo di Pero, 14th-century artists of the Sienese School.

The Romanesque Pieve of Corsignano is located in the neighbourhood. The monastery of Sant'Anna in Camprena was founded in 1332-1334 by Bernardo Tolomei as a hermitage for the Benedictines; it was remade in the late 15th-early 16th century, and several times in the following centuries. The refectory houses frescoes by il Sodoma (1502–1503).

Monticchiello

The frazione of Monticchiello is home to a characteristic Romitorio, a series of grottoes carved in the rock by hermit monks. In the same locality is the pieve of Santi Leonardo e Cristoforo, rebuilt in the 13th century in Gothic style. The interior has frescoes from a 14th-century Sienese painter, a cyborium in the shape of a small Gothic portal and an alte 15th-century Crucifix. At San Pietro in Campo are the remains of the eponymous abbey.

Monticchiello is the subject of the documentary Spettacolo.

References

- ↑ Adams 1985, p. 99–110. Adams details the piecemeal acquisition of parcels of land by Pius II.

- 1 2 Tönnesmann 2013, p. 35

- ↑

- ↑ Haegen, Anne Mueller von der; Strasser, Ruth F. (2013). "Pienza". Art & Architecture: Tuscany. Potsdam: H.F.Ullmann Publishing. pp. 394–395. ISBN 978-3-8480-0321-1.

- ↑ "As you enter the middle door, the entire church with its altars and chapels is visible and is remarkable for the clarity of the light and the brilliance of the whole edifice. There are three naves, as they are called. The middle one is wider. All are the same height. This was according to the directions of Pius, who had seen the plan among the Germans in Austria" Quoted in Henk W. van Os, "Painting in a House of Glass: The Altarpieces of Pienza" Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art 17.1 (1987, pp. 23-38)

- ↑ Diocesan Museum.

Sources

- Adams, Nicholas (May 1985). "The Acquisition of Pienza, 1459-1464". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 44 (2): 99–110.

- Adams, Nicholas (1989). "The Construction of Pienza (1459-1464) and the Consequences of Renovatio". In Zimmerman, Susan; Weissman, Ronald. Urban Life in the Renaissance. Newark: Univ. of Delaware Press. pp. 50–79.

- Carli, Enzo (1966). Pienza: la Citta di Pio II. Rome: Editalia.

- Cataldi, Giancarlo; Formichi, Fausto (2007). Pienza Forma Urbis. Florence: Aion Edizioni.

- Charles, Mack (2012). "Beyond the Monumental:The Semiotics of Papal Authority in Renaissance Pienza". Southeastern College Art Conference Review. 16 (2): 124–50.

- Mack, Charles (1987). Pienza: the Creation of a Renaissance City. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Mayernik, David (2003). Timeless Cities: An Architect's Reflections on Renaissance Italy. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Piccolomini, Aeneas Silvius (1959). Gabel, Leona, ed. Memoirs of a Renaissance Pope. Translated by Gragg, Florence. New York: Capricorn Books.

- Pieper, Jan (1997). Pienza: der Entwurf einer humanistischen Weltansicht. Stuttgart: Axel Menges.

- Smith, Christine (1992). Architecture in the Culture of Early Humanism: Ethics, Aesthetics, and Eloquence, 1400-1470. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tönnesmann, Andreas (2013) [First published 1990]. Pienza: Städtebau und Humanismus (in German) (3rd ed.). Munich: Hirmer. ISBN 978-3-8031-2717-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pienza. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Pienza. |