Ornithine transcarbamylase

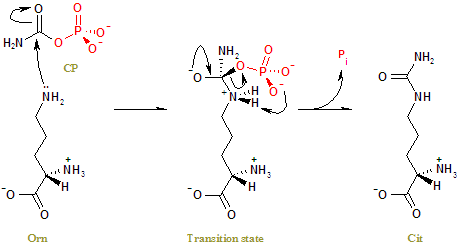

Ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) (also called ornithine carbamoyltransferase) is an enzyme (EC 2.1.3.3) that catalyzes the reaction between carbamoyl phosphate (CP) and ornithine (Orn) to form citrulline (Cit) and phosphate (Pi). In plants and microbes, OTC is involved in arginine (Arg) biosynthesis, whereas in mammals it is located in the mitochondria and is part of the urea cycle.

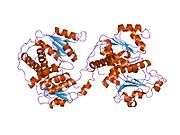

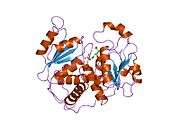

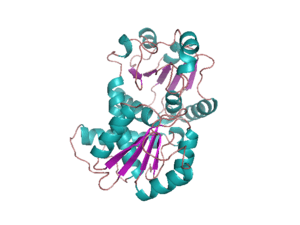

Structure

OTC is a trimer. The monomer unit has a CP-binding domain and an amino acid-binding domain. Each of the two discrete substrate-binding domains (SBDs) have an α/β topology with a central β-pleated sheet embedded in flanking α-helices.

The active sites are located at the interface between the protein monomers.

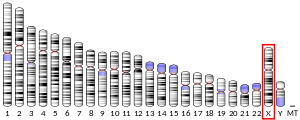

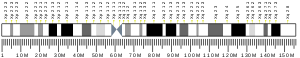

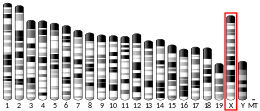

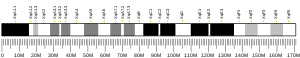

Genomics

The gene is located on the short arm of chromosome X (Xp11.4[5]). The gene is located in the Watson (plus) strand and is 68,968 bases in length. The encoded protein is 354 amino acids long with a predicted molecular weight of 39.935 kiloDaltons. The protein is located in the mitochondrial matrix.

Function

The side-chain amino group of Orn attacks the carbonyl carbon of CP nucleophilically, left, to form a tetrahedral transition state, middle. Charge rearrangement releases Cit and Pi, right.[6]

Deficiency

If a person is deficient in OTC, ammonia levels will build up, and this will cause neurological problems. Levels of the amino acids glutamate and alanine will be increased (as these are the amino acids that receive nitrogen from others).

Because newborns are usually discharged from the hospital within 1–2 days after birth, the symptoms of a urea cycle disorder are often not seen until the child is at home and may not be recognized in a timely manner by the family and primary-care physician. The typical initial symptoms of a child with hyperammonemia are non-specific: failure to feed, loss of thermoregulation with a low core temperature, and somnolence. Symptoms progress from somnolence to lethargy and coma. Abnormal posturing and encephalopathy are often related to the degree of central nervous system swelling and pressure upon the brainstem. About 50% of neonates with severe hyperammonemia have seizures.

Hyperventilation, secondary to cerebral edema, is a common early finding in a hyperammonemic attack, which causes a respiratory alkalosis. Hypoventilation and respiratory arrest follow, as pressure increases on the brainstem. In milder (or partial) urea cycle enzyme deficiencies, ammonia accumulation may be triggered by illness or stress at almost any time of life, resulting in multiple mild elevations of plasma ammonia concentration [Bourrier et al. 1988]. The hyperammonemia is less severe and the symptoms more subtle. In patients with partial enzyme deficiencies, the first recognized clinical episode may be delayed for months or years. One in 70000 adults has an ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency.

Levels of urea cycle intermediates may be decreased, as carbamoyl phosphate cannot replenish the cycle. The carbamoyl phosphate instead goes into the uridine monophosphate synthetic pathway. Here, orotic acid (one step of this alternative pathway) levels in the blood are increased.

A potential treatment for the high ammonia levels is to give sodium benzoate, which combines with glycine to produce hippurate, at the same time removing an ammonium group. Biotin also plays an important role in the functioning of the OTC enzyme[7] and has been shown to reduce ammonia intoxication in animal experiments.

References

- 1 2 3 GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000036473 - Ensembl, May 2017

- 1 2 3 GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000031173 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ↑ "Human PubMed Reference:".

- ↑ "Mouse PubMed Reference:".

- ↑ "ORNITHINE CARBAMOYLTRANSFERASE; OTC". Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. NHGRI. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ↑ Langley DB, Templeton MD, Fields BA, Mitchell RE, Collyer CA (June 2000). "Mechanism of inactivation of ornithine transcarbamoylase by Ndelta -(N'-Sulfodiaminophosphinyl)-L-ornithine, a true transition state analogue? Crystal structure and implications for catalytic mechanism". J. Biol. Chem. 275 (26): 20012–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M000585200. PMID 10747936.

- ↑ Nagamine T, Saito S, Kaneko M, Sekiguchi T, Sugimoto H, Takehara K, Takagi H (June 1995). "Effect of biotin on ammonia intoxication in rats and mice". J. Gastroenterol. 30 (3): 351–5. doi:10.1007/bf02347511. PMID 7647902.

Further reading

- Tuchman M, Plante RJ (1995). "Mutations and polymorphisms in the human ornithine transcarbamylase gene: mutation update addendum". Hum. Mutat. 5 (4): 293–5. doi:10.1002/humu.1380050404. PMID 7627182.

- Tuchman M (1993). "Mutations and polymorphisms in the human ornithine transcarbamylase gene". Hum. Mutat. 2 (3): 174–8. doi:10.1002/humu.1380020304. PMID 8364586.

- Matsuda I, Tanase S (1997). "The ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) gene: mutations in 50 Japanese families with OTC deficiency". Am. J. Med. Genet. 71 (4): 378–83. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19970905)71:4<378::AID-AJMG2>3.0.CO;2-Q. PMID 9286441.

- Wakabayashi Y (1999). "Tissue-selective expression of enzymes of arginine synthesis". Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 1 (4): 335–9. doi:10.1097/00075197-199807000-00004. PMID 10565370.

- Tuchman M, Jaleel N, Morizono H, et al. (2002). "Mutations and polymorphisms in the human ornithine transcarbamylase gene". Hum. Mutat. 19 (2): 93–107. doi:10.1002/humu.10035. PMID 11793468.

- Feldmann D, Rozet JM, Pelet A, et al. (1992). "Site specific screening for point mutations in ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency". J. Med. Genet. 29 (7): 471–5. PMC 1016021. PMID 1353535.

- Tuchman M, Holzknecht RA, Gueron AB, et al. (1993). "Six new mutations in the ornithine transcarbamylase gene detected by single-strand conformational polymorphism". Pediatr. Res. 32 (5): 600–4. doi:10.1203/00006450-199211000-00024. PMID 1480464.

- Dawson SJ, White LA (1992). "Treatment of Haemophilus aphrophilus endocarditis with ciprofloxacin". J. Infect. 24 (3): 317–20. doi:10.1016/S0163-4453(05)80037-4. PMID 1602151.

- Suess PJ, Tsai MY, Holzknecht RA, et al. (1992). "Screening for gene deletions and known mutations in 13 patients with ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency". Biochem. Med. Metab. Biol. 47 (3): 250–9. doi:10.1016/0885-4505(92)90033-U. PMID 1627356.

- Grompe M, Caskey CT, Fenwick RG (1991). "Improved molecular diagnostics for ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 48 (2): 212–22. PMC 1683033. PMID 1671317.

- Hentzen D, Pelet A, Feldman D, et al. (1992). "Fatal hyperammonemia resulting from a C-to-T mutation at a MspI site of the ornithine transcarbamylase gene". Hum. Genet. 88 (2): 153–6. doi:10.1007/bf00206063. PMID 1721894.

- Strautnieks S, Rutland P, Malcolm S (1992). "Arginine 109 to glutamine mutation in a girl with ornithine carbamoyl transferase deficiency". J. Med. Genet. 28 (12): 871–4. doi:10.1136/jmg.28.12.871. PMC 1017166. PMID 1757964.

- Carstens RP, Fenton WA, Rosenberg LR (1991). "Identification of RNA splicing errors resulting in human ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 48 (6): 1105–14. PMC 1683104. PMID 2035531.

- Hata A, Matsuura T, Setoyama C, et al. (1991). "A novel missense mutation in exon 8 of the ornithine transcarbamylase gene in two unrelated male patients with mild ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency". Hum. Genet. 87 (1): 28–32. doi:10.1007/BF01213087. PMID 2037279.

- Legius E, Baten E, Stul M, et al. (1990). "Sporadic late onset ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency in a boy with somatic mosaicism for an intragenic deletion". Clin. Genet. 38 (2): 155–9. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.1990.tb03565.x. PMID 2208768.

- Finkelstein JE, Francomano CA, Brusilow SW, Traystman MD (1990). "Use of denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis for detection of mutation and prospective diagnosis in late onset ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency". Genomics. 7 (2): 167–72. doi:10.1016/0888-7543(90)90537-5. PMID 2347583.

- Grompe M, Muzny DM, Caskey CT (1989). "Scanning detection of mutations in human ornithine transcarbamoylase by chemical mismatch cleavage". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86 (15): 5888–92. doi:10.1073/pnas.86.15.5888. PMC 297736. PMID 2474822.

- Lee JT, Nussbaum RL (1990). "An arginine to glutamine mutation in residue 109 of human ornithine transcarbamylase completely abolishes enzymatic activity in Cos1 cells". J. Clin. Invest. 84 (6): 1762–6. doi:10.1172/JCI114360. PMC 304053. PMID 2556444.

- Chu TW, Eftime R, Sztul E, Strauss AW (1989). "Synthetic transit peptides inhibit import and processing of mitochondrial precursor proteins". J. Biol. Chem. 264 (16): 9552–8. PMID 2722850.

- Hata A, Setoyama C, Shimada K, et al. (1989). "Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency resulting from a C-to-T substitution in exon 5 of the ornithine transcarbamylase gene". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 45 (1): 123–7. PMC 1683378. PMID 2741942.

- Summar ML, Tuchman M (29 April 2003). "Urea Cycle Disorders Overview" (PDF). University of Washington, Seattle.