Niqāb

.jpg)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic culture |

|---|

| Architecture |

| Art |

| Dress |

| Holidays |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Theatre |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) |

|---|

| Islamic studies |

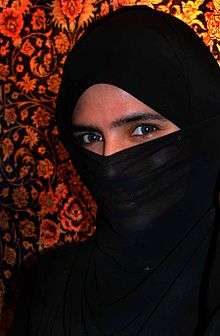

A niqab or niqāb (/nɪˈkɑːb/; Arabic: نِقاب niqāb, "[face] veil"; also called a ruband) is a garment of clothing that covers the face, worn by a small minority of Muslim women as a part of a particular interpretation of hijab ("modesty"). According to the majority of Muslim scholars and Islamic schools of thought, the niqab is not a requirement of Islam; however a minority of Muslim scholars assert that the niqab is required, especially in the Hanbali Muslim faith tradition. Those Muslim women who observe the niqab, wear it in public areas and in front of non-mahram (non-related) men.

The face veil pre-dates Islam, and had been used by certain Arabian pre-Islamic cultures. Culturally, it is "a custom imported from Najd, a region in Saudi Arabia and the power base of its Salafi fundamentalist form of Islam. Within Muslim countries it is very contested and considered fringe."[1]

Today, the niqab is most often worn in its region of origin: the Arab countries of the Arabian Peninsula — Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates. However, even in these countries, the niqab is neither a universal cultural custom nor is it culturally compulsory. In other parts of the Muslim world outside of the Arabian Peninsula, where the niqab has slowly spread to a much smaller extent, it is regarded warily by Sunni and non-Sunni Muslims alike "as a symbol of encroaching fundamentalism."[2] Nevertheless, the niqab is worn by a small minority of Muslims in not only Muslim-majority regions such as Somalia, Syria, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Bangladesh, the Palestinian territories, and Southern Iran, but also among a minority of Muslims in regions where Muslims are themselves a minority, like India and Europe.

The terms niqab and burqa are often conflated; a niqab covers the face while leaving the eyes uncovered, while a burqa covers the entire body from the top of the head to the ground, with only a mesh screen allowing the wearer to see in front of her.

Etymology

Women who wear the niqab are often called niqābīah; this word is used both as a noun and as an adjective. However, the correct form منتقبة muntaqabah / muntaqibah (plural muntaqabāt / muntaqibāt) as niqābīah is used in a derogatory manner (much as with ḥijābīah versus محجبة muḥajjabah).[4] Colloquially, women in niqab are called منقبة munaqqabah, with the plural منقبات munaqqabāt.

Overview

Pre-Islamic use of the face veil

The face-veil was originally part of women's dress among certain classes in the Byzantine Empire and was adopted into Muslim culture during the Arab conquest of the Middle East.[5]

However, although Byzantine art before Islam commonly depicts women with veiled heads or covered hair, it does not depict women with veiled faces. In addition, the Greek geographer Strabo, writing in the first century AD, refers to some Median women veiling their faces;[6] and the early third-century Christian writer Tertullian clearly refers in his treatise The Veiling of Virgins to some "pagan" women of "Arabia" wearing a veil that covers not only their head but also the entire face.[7] Clement of Alexandria commends the contemporary use of face coverings.[8][9] There are also two Biblical references to the employment of covering face veils in Genesis 38.14 and Genesis 24.65, by Tamar and by Rebeccah, Judah and Abraham's daughters-in-law respectively.[10][11][12] These primary sources show that some women in Egypt, Arabia, Canaan and Persia veiled their faces long before Islam. In the case of Tamar, the Biblical text, 'When Judah saw her, he thought her to be a harlot; because she had covered her face' indicates customary, if not sacral, use of the face veil to accentuate rather than disguise sexuality.[13]

Niqab in Islam

Views among Muslim scholars

There is a difference of opinion and interpretation amongst scholars in Islam as to the permissibility or prohibition of covering the face. These fall into three different general interpretations, one held by a majority and two held by a minority.

The first interpretation, the opinion of the overwhelming majority of Islamic scholars, states that the niqab is optional at most. Within this view, there is disagreement as to when the niqab becomes prohibited even for those who would choose to wear it at other times.

The second interpretation, the opinion of a small minority of Islamic scholars, states that the niqab is outright obligatory (fard) to wear at all times in the presence of non-mahram males.

The third interpretation, also a small minority opinion, states that the niqab is outright prohibited and against Islam to wear at any time, in any company.

The niqab has continued to arouse debate between Muslim scholars and jurists both past and present concerning whether it is prohibited, fard (obligatory), mustahabb (recommended/preferable), or 'urf (cultural).[14][15]

Not obligatory (not fard)

According to the rulings of mainstream Sunni Islam, nothing at all is mentioned of niqab in the Qur'an. Moreover, even in some Hadith, it is clearly stated that the Prophet Muhammad himself taught women, in the example of his companion Abu Bakr's daughter Asma' bint Abu Bakr, that they need not veil (niqab) either their face or their hands:

"O Asma', when a woman reaches the age of puberty, nothing should be seen of her except for this and this; the hands and the face."

Although there is no Islamic scripture, neither Quaranic nor Hadith, where females are required to cover their face and hands, there is on the contrary a Hadith where it is narrated that the Prophet himself taught, in accordance to his Sunnah, that it is in fact forbidden (haraam), at least during Hajj and Umrah, for females to veil (niqab) their face, even if at other times the female insists on wearing niqab, against Islamic scripture:

"It is forbidden for a woman who is in the state of Ihram to cover her face."

Prohibited innovation/cultural practice debate

Within the majority Islamic legal opinion that the niqab is never obligatory, different schools and scholars disagree as to whether wearing niqab at any time (not just during Hajj and Umrah) is 'urf (a cultural practice) which should merely be discouraged; or if it is bid'ah say'iah, an innovation which opposes the Qur'an and Sunnah contrary to Islam, and is to be prohibited.

In deference to the minority legal opinion which rules niqab to be obligatory, most other Muslim scholars and Islamic schools of thought have ruled that the preference is not to prohibit niqab as bid'ah say'iah, but as 'urf to be discouraged.

There are, nevertheless, scholars who have issued fatwas decreeing niqab to be against Islam, including the Grand Mufti of Egypt. Notably, the niqab is condemned for the Sunni Islamic world by the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar, Sheikh Haji Muhammad Sayyid Tantawy, in his 7000-page Exegesis (Tafsir) of Al-Qur'an, written over 10 years. A renowned scholar and head of the Islamic world's preeminent religious institute, Tantawy has stated that "the niqab is a cultural tradition and has nothing to do with Islam."[18] His comments followed an incident in which he forced a school girl to remove her niqab during a visit to an Al-Azhar school, when Tantawy reportedly said that he would call for an official ban for the face veil in Islamic schools.

Tantawy's decision stems from his views that younger Muslims have lost touch with traditional Islamic scholarship and have come under the influence of imams from the Salafi (Wahhabi) branch in Saudi Arabia.[19] Sharia law, according to certain public commentators (e.g., Mudar Zahran) and Islamic scholars, in fact bans women from wearing the niqab in Mecca during worship.

In the majority opinion of Islamic scholars, a woman or girl may lawfully wear the niqab, but in return may not criticize other Muslim women who properly cover their bodies, but do not wear the niqab to cover their face (i.e. hijabis). The niqabi (niqab wearer) is also prohibited from pressing the practice on others. In this practice of mutual tolerance, the niqabi shall also not be criticized for her belief or tradition holding niqab to be obligatory, or for her good-faith error on the side of modesty.

Sunni

The opinions of the four traditional mainstream Sunni schools of jurisprudence are as follows:

- Maliki: In the Maliki madhhab, the face and the hands of a woman are not awrah; therefore covering the face is not obligatory. However, Maliki scholars have stated that it is highly recommended (mustahabb) for women to cover their faces.

- Hanafi: The Hanafi school does not consider a woman's face to be awrah; however it is still obligatory (wajib) for a woman to cover her face. While the Hanafi school has not completely forbidden a male's gaze towards a female's face when there exists absolutely no fear of attraction, the woman has no way of knowing whether the gazes directed towards her are free of desire or not, especially when she is out in public. The Hanafi school has thus obliged women to cover their faces in front of strangers.[20][21]

- Shafi'i: The Shafi'i school has had two well-known positions on this issue. The first view is that covering of the face is not obligatory (fard).[22] The second view is that covering the face is obligatory only in times of fitnah (where men do not lower their gaze; or when a woman is very attractive).[23]

- Hanbali: According to the Hanbali school, there are two differing views on whether a woman's whole body is awrah or not. Mālik, Awzāʿī, and Shafiʿī suggest that the awrah of a woman is her entire body excluding her face and her hands. Hence, covering the face would not be obligatory (fard) in this madhhab.[24]

According to scholars like Tirmidhī and Ḥārith b. Hishām, however, all of a woman's body is awrah, including her face, hands, and even fingernails. There is a dispensation though that allows a woman to expose her face and hands, e.g. when asking for her hand in marriage, because it is the centre of beauty.[25]

Salafi views

According to the Salafi point of view, it is obligatory (fard) for a woman to cover her entire body when in public or in presence of non-mahram men.[26][27] Some interpretations say that a veil is not compulsory in front of blind, asexual or gay men.[28][29][30]

The Islamic scholar Muhammad Nasiruddin al-Albani, while a teacher at Islamic University of Madinah, wrote a book supporting his view that the niqab is not a binding obligation upon Muslim women. His opponents within the Saudi establishment ensured that his contract with the university was allowed to lapse without renewal.[31]

Shia

In the Shi'a Ja'fari school of fiqh, covering the face is not obligatory.[32] However, the Shia religious leadership is divided on the issue of niqab. For example, Ayatollah Abu al-Qasim al-Khoei was among the learned who, based upon the Quran and the hadith, believed that women should wear the niqab as per "obligatory precaution (Ihtiyat wujubi).[33] Many Shia women living in countries such as Bahrain, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia or Iraq wear it on a daily basis.

Rationale

The claimed rationale of the niqab comes from Hadith. It was known that the wives of the Prophet Muhammad covered themselves around non-mahram men. However the Quran explicitly states that the wives of the Prophet are held to a different standard.[34] It is claimed that under Islam the niqab is a requirement for the wives of Muhammad.[35] The following verse from the Qur'an is cited as support for this:[36]

"O Prophet! Tell your wives and your daughters, and the nisā’il-mu’minīn (Arabic: نِـسَـاءِ الْـمُـؤْمِـنِـيْـن, "women of the believers"), to draw ‘alayhinna (Arabic: عَـلَـيْـهِـنَّ, "over them" (feminine tense)) of their jalābīb (Arabic: جَـلَابِـيْـب, cloaks or veils). That will be better that yu‘rafna (Arabic: يُـعْـرَفْـنَ, they should be known (as respectable woman)) so as not to be annoyed. And Allah is Ever Oft-Forgiving, Most Merciful."[Quran 33:59 (Translated by Ahmed Ali)]

This verse was in response to harassment on the part of the "hypocrites",[37] although it does not clearly refer to covering the face itself. It is also argued by some Muslims that the reasons for the niqab are to keep Muslim women from worrying about their appearances and to conceal their looks.[36][38]

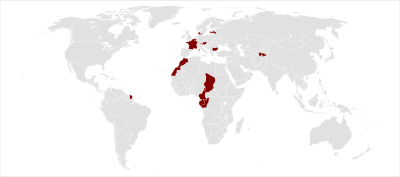

Criminalization and bans

The niqab is controversial in Europe. In France specifically, although the niqab is not individually targeted, it falls within the scope of legislation which bans the wearing of any religious items (Christian, Jewish, Muslim, or other) in certain public areas.

In 2004, the French Parliament passed a law to regulate "the wearing of symbols indicating religious affiliation in public educational establishments".[39] This law forbids all emblems that outwardly express a specific religious belief to be worn in French public schools.[39] This law was proposed because the Stasi Commission, a committee that is supposed to enforce secularity in French society, was forced to deal with frequent disputes about headscarves in French public schools, as outsiders of the practice did not understand the scarves’ purpose and therefore felt uncomfortable.[39]

Although the French law addresses other religious symbols – not just Islamic headscarves and face coverings – the international debate has been centered around the impact it has on Muslims because of the growing population in Europe, especially France, and the increase in Islamophobia.[39]

In July 2010, the National Assembly in France passed Loi Interdisant La Dissimulation Du Visage Dans L'espace Public, (Act Prohibiting Concealment of the Face in Public Space). This act outlawed the wearing of clothing that covers one's face in any public space.[40][41] Violators of the ban on veils and coverings are liable to fines of up to 150 Euros and mandatory classes on French citizenship.[42] Anyone found to have forced a woman to wear a religious covering faces up to two years in prison as well as a 60,000 Euro fine.[42]

The then president of France, Nicolas Sarkozy publicly stated "The burqa is not welcome in France because it is contrary to our values and the ideals we have of a woman's dignity". Sarkozy further explained that the French government sees these enactments as a way to successfully ease Muslims into French society and to promote gender equality.[40]

Styles

There are many styles of niqab and other facial veils worn by Muslim women around the world. The two most common forms are the half niqab and the gulf-style or full niqab.

The half niqab is a simple length of fabric with elastic or ties and is worn around the face. This garment typically leaves the eyes and part of the forehead visible.

The gulf-style or full niqab completely covers the face. It consists of an upper band that is tied around the forehead, together with a long wide piece of fabric which covers the face, leaving an opening for the eyes. Many full niqab have two or more sheer layers attached to the upper band, which can be worn flipped down to cover the eyes or left over the top of the head. While a person looking at a woman wearing a niqab with an eyeveil would not be able to see her eyes, the woman wearing the niqab would be able to see out through the thin fabric.

Other less common and more cultural or national forms of niqab include the Afghan style burqa, a long pleated gown that extends from the head to the feet with a small crocheted grille over the face. The Pak Chador is a relatively new style from Pakistan, which consists of a large triangular scarf with two additional pieces.[4] A thin band on one edge is tied behind the head so as to keep the chador on, and then another larger rectangular piece is attached to one end of the triangle and is worn over the face, and the simple hijāb wrapped, pinned or tied in a certain way so as to cover the wearer's face.

Other common styles of clothing popularly worn with a niqab in Western countries include the khimar, a semi-circular flare of fabric with an opening for the face and a small triangular underscarf. A khimar is usually bust-level or longer, and can also be worn without the niqab. It is considered a fairly easy form of headscarf to wear, as there are no pins or fasteners; it is simply pulled over the head. Gloves are also sometimes worn with the niqab, because many munaqqabāt believe no part of the skin should be visible other than the area immediately around the eyes or because they do not want to be put in a position where they would touch the hand of an unrelated man (for instance, when accepting change from a cashier). Most munaqqabāt also wear an overgarment (jilbab, abaya etc.) over their clothing, though some munaqabat in Western countries wear a long, loose tunic and skirt instead of a one-piece overgarment.

In different countries

Egypt

The niqab in Egypt has a complex and long history. On 8 October 2009, Egypt's top Islamic school and the world's leading school of Sunni Islam, Al-Azhar, banned the wearing of the niqab in classrooms and dormitories of all its affiliate schools and educational institutes.[43]

Iran

The niqab was traditionally worn in Southern Iran from the arrival of Islam until the end of the Qajar era. There were many regional variations of niqab, which were also called ruband or pushiye. Traditionally, Iranian women wore chadors long before Islam arrived.

The 20th century ruler, Reza Shah, banned all variations of face veil in 1936, as incompatible with his modernistic ambitions. Reza Shah ordered the police to arrest women who wore the niqab and to remove their face veils by force. This policy outraged the clerics who believed it was obligatory for women to cover their faces. Many women gathered at the Goharshad Mosque in Mashhad with their faces covered to show their objection to the niqab ban.[44]

Between 1941 and 1979 wearing the niqab was no longer against the law, but it was considered by the government to be a "badge of backwardness." During these years, wearing the niqab and chador became much less common and instead most religious women wore headscarves only. Fashionable hotels and restaurants refused to admit women wearing niqabs. High schools and universities actively discouraged or even banned the niqab, though the headscarf was tolerated.[45]

After the new government of 'Islamic Republic' was established, the niqab ban was not enforced by officials.

In modern Iran, the wearing of niqab is not common and is only worn by certain ethnic minorities and a minority of Arab Muslims in the southern Iranian coastal cities, such as Bandar Abbas, Minab and Bushehr. Some women in the Arab-populated province of Khuzestan still wear niqab.

Pakistan

In 2015, the constitutional Council of Islamic Ideology issued the fatwa that women are not required to wear niqab or cover their hands or feet under Shariah.[46]

Saudi Arabia

Saudi women are not required by a secular law to wear the niqab. However, the niqab is an important part of Saudi culture and in most Saudi cities (including Riyadh, Mecca, Medina, Abha, etc.) the vast majority of women cover their faces. The Saudi niqab usually leaves a long open slot for the eyes; the slot is held together by a string or narrow strip of cloth.[47] In 2008, the Mohammad Habadan, a religious authority in Mecca, reportedly called on women to wear veils that reveal only one eye, so that women would not be encouraged to use eye make-up.[48]

Syria

1,200 niqab-wearing teachers were transferred to administrative duties in the summer of 2010 in Syria because the face veil was undermining the secular policies followed by the state as far as education is concerned.[49] In the summer of 2010, students wearing the niqab were prohibited from registering for university classes. The ban was associated with a move by the Syrian government to re-affirm Syria's traditional secular atmosphere.[50]

On 6 April 2011 it was reported that teachers would be allowed to once again wear the niqab.[51]

Yemen

Since antiquity, the Arab tradition of wearing the niqab has been practiced by women living in Yemen.[52] Traditionally, girls begin wearing veils in their teenage years.[53][54]

Acceptance of the niqab is not universal in Yemen. Senior member of the Al-Islah political party, Tawakel Karman, removed her niqab at a human rights conference in 2004 and since then has called for "other women and female activists to take theirs off".[55]

Enforcement, encouragement and bans

Enforcement

Covering the face was enforced by the Taliban regime with the traditional Afghan face veil called the burka.[56]

Politics

The niqab is outlawed in Azerbaijan, where the overwhelming majority of the population is Muslim. Niqabi women, just like women wearing hijab, cannot work as public servants, neither can they continue studies at schools, including the private schools. Although there is no single law banning niqab at private companies, it would be nearly impossible for a niqabi woman to find work.

In February 2010, an Arab country's unnamed ambassador to Dubai had his marriage annulled after discovering that his bride was cross-eyed and had facial hair. The woman had worn a niqab on the occasions that the couple had met prior to the wedding. The ambassador informed the Sharia court that he had been deliberately deceived by the bride's mother, who had shown him photographs of the bride's sister. He only discovered this when he lifted the niqab to kiss his bride. The court annulled the marriage, but refused a claim for compensation.[57][58][59]

Sultaana Freeman gained national attention in 2003 when she sued the US state of Florida for the right to wear a niqab for her driver's license photo.[60] However, a Florida circuit court ruled there was no violation in the state requiring her to show her face to a camera in a private room with only a female employee to take the picture, in exchange for the privilege of driving.[61] The ruling was affirmed by the appellate court.[62]

One female non-Muslim student at Eastern Michigan University spent a semester in 2005 wearing a niqab for a class project (she referred to the face veil as a "burqa"). Her stated experiences, such as her own feeling as if no one wanted to be near her, led her to assert that conservative Muslim dress is disapproved of in the United States.[63]

Some Muslim Palestinian women, particularly students, have worn white niqabs during Arab protest activities relating to the Arab–Israeli conflict.[64][65] These women have reportedly worn green banners with Arabic messages in them.

In 2006, Female candidates from the Hamas party campaigned during the Palestinian Authority parliamentary elections, wearing niqabs. Since Hamas seized control of Gaza from Fatah during the Battle of Gaza (2007), Muslim women in Gaza have been wearing, or were mandated to wear, niqabs in increasingly large numbers[66][67]

Africa

Cameroon

In July 2015, Cameroon banned the face veil including the burqa after two women dressed in the religious garments completed a suicide attack killing 13.[68][69] This was also done in order to counter extremism in public and places of work.[70]

Chad

In June 2015, the full face veil was banned in Chad after veiled Boko Haram bombers disguised as women completed multiple suicide attacks.[69][71][72]

Republic of the Congo

In May 2015, the Republic of the Congo banned the face veil in order to counter extremism.[73][74] The decision was announced by El Hadji Djibril Bopaka, the president of the country's Islamic High Council.[75]

Morocco

The Moroccan government distributed letters to businesses on 9 January 2017 declaring a ban on the burka. The letters indicated the "sale, production and import" or the garment were prohibited and businesses were expected to clear their stock within 48 hours.[76]

Asia-Pacific

Australia

In May 2010, an armed robbery committed by a man wearing a face veil and sunglasses raised calls to ban the Islamic veil; a request for new legislation was dismissed by both Prime Minister Kevin Rudd and Liberal leader Tony Abbott.[77]

Tajikistan

In 2017 the government of Tajikistan passed a law requiring people to "stick to traditional national clothes and culture", which has been widely seen as an attempt to prevent women from wearing Islamic clothing, in particular the style of headscarf wrapped under the chin, in contrast to the traditional Tajik headscarf tied behind the head.[78]

Europe

.jpg)

Although the burqa is a more emphatic symbol, the niqab has also been prominent in political controversies on Islamic dress in Europe.

In Yugoslavia wearing the niqab or forcing women to wear it were forbidden in order to prevent the subjugation of women to men.

Netherlands

In 2007, the government of the Netherlands planned a legal ban on face-covering Islamic clothing, popularly described as the 'burqa ban', which included the niqab.[79] In 2015, a partial ban of the niqab and burqa were approved by the Dutch government.[80] The parliament still had to approve the measure.[80] In November 2016, the legal ban on face-covering was approved by parliament.[81] On 26 June 2018, a partial ban on face covering (including niqabs) on public transport and in buildings and associated yards of educational institutions, governmental institutions and healthcare institutions was enacted, with a number of exceptions.[82]

Belgium

On 29 April 2010, the Belgian Chamber of Representatives adopted a law prohibiting people to wear "attire and clothing masking the face in such a way that it impairs recognizability". The penalty for violating this directive can run from up to 14 days imprisonment and a 250 euro fine.

In August 2014, the Chief of Protocol for the city of Brussels Jean-Marie Pire tore the niqab off a Qatari princess who had asked him for directions in Brussels.[83] On 11 July 2017 the ban in Belgium was upheld by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) after having been challenged by two Muslim women who claimed their rights had been infringed.[84]

Denmark

In autumn 2017, the Danish parliament (Danish: Folketinget) agreed to adopt a law prohibiting people to wear "attire and clothing masking the face in such a way that it impairs recognizability". [85][86] A full ban on both niqabs and burqas was announced on 31 May 2018.[87] The ban came into force on 1 august 2018 and carries a fine of 1000 DKK, about 134 euro, by repeat offending the fine may reach 10 000 DKK.[88] Then targets all garments that covers the face, such as fake beards or balaclavas.[89] Supporters of the ban claim that the ban facilitates integration of Muslims into Danish society while Amnesty International claimed the ban violated women's rights.[89] A protest numbering 300-400 people was held in the Nørrebro district of Copenhagen organised by Socialist Youth Front, Kvinder i Dialog and Party Rebels.[90]

The first fine was issued in Hørsholm in August 2018 to a woman dressed in a niqab who was in a fistfight with another woman on an escalator in a shopping centre. During the fight their her face-covering veil fell off, but as police approached, she put them on again and police issued the fine.[91] Both women were suspected of public order violations.[91]

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, comments by Jack Straw, MP started a national debate over the wearing of the "veil" (niqab), in October 2006. Around that time there was media coverage of the case of Aishah Azmi, a teaching assistant in Dewsbury, West Yorkshire, who lost her appeal against suspension from her job for wearing the niqab while teaching English to young children. It was decided that being unable to see her face prevented the children from learning effectively. Azmi, who had been interviewed and hired for the position without the niqab, allegedly on her husband's advice, argued it was helping the children understand different people's beliefs.[92] In 2010, a man committed a bank robbery wearing a niqab as a disguise.[93]

France

On 13 July 2010 France's lower house of parliament overwhelmingly approved a ban on wearing burqa-style Islamic veils. The legislation forbids face-covering Muslim veils in all public places in France and calls for fines or citizenship classes, or both. The bill also is aimed at husbands and fathers — anyone convicted of forcing someone else to wear the garb risks a year of prison and a fine, with both penalties doubled if the victim is a minor.

Italy

In Italy, a law issued in 1975 strictly forbids wearing of any attire that could hide the face of a person. Penalties (fines and imprisonment) are provided for such behaviour. The original purpose of the anti-mask law was to prevent crime or terrorism. The law allows for exemptions for a "justified cause", which has sometimes been interpreted by courts as including religious reasons for wearing a veil, but others –including local governments– disagree and claim religion is not a "justified cause" in this context.[94]

Norway

In 2012 in Norway, a professor at the University of Tromsø denied a student's use of niqab in the classroom.[95] The professor claimed Norway's parliament granted each teacher the right to deny the use of niqab in his/her classroom.[95] Clothing that covers the face, such as a niqab, is prohibited in some schools and municipalities.[96][97][98]

In autumn 2017, Norway government adopted a law prohibiting people to wear "attire and clothing masking the face in such a way that it impairs recognizability" in schools and in universities.[99]

The Prime Minister of Norway Erna Solberg stated in an interview that in Norwegian work environments it is essential to see each other's faces and therefore anyone who insists on wearing a niqab is in practice unemployable. Solberg also views the wearing of the niqab as a challenge to social boundaries in the Norwegian society, a challenge that would be countered by Norway setting boundaries of its own. Solberg also stated that anyone may wear what they wish in their spare time and that her comments applied to professional life but that any immigrant has the obligation to adapt to Norwegian work life and culture.[100]

In June 2018, the parliament of Norway passed a bill banning clothing covering the face at educational institutions as well as daycare centres, which included face-covering Islamic veils. The prohibition applies to pupils and staff alike.[101][102]

Latvia

In 2016, a legal ban on face-covering Islamic clothing was proposed for adoption by the Latvian parliament.[103]

Bulgaria

In 2016, a legal ban on face-covering Islamic clothing was adopted by the Bulgarian parliament.[104]

Austria

In 2017, a legal ban on face-covering Islamic clothing was adopted by the Austrian parliament.[105]

Germany

In 2017, a legal a ban on face-covering clothing for soldiers and state workers during work was approved by German parliament.[106] Also in 2017, a legal ban on face-covering clothing for car and truck drivers was approved by German Ministry of Traffic.[107]

In July 2017, German state Bavaria approved a legal ban on face-covering clothing for teachers, state workers and students at university and schools.[108] In August 2017, the state of Lower Saxony (German: Niedersachsen) banned the burqa along with the niqab in public schools. This change in the law was prompted by a Muslim pupil in Osnabrück who wore the garment to school for years and refused to take it off. Since she has completed her schooling, the law was instituted to prevent similar cases in the future.[109]

Sweden

In 2012, a poll by Uppsala University found that Swedes responded that face-covering Islamic veils are either completely unacceptable or fairly unacceptable, 85% for the burqa and 81% for the niqāb. The reserachers noted these figures reprented a compact resistance to the face-covering veil by the population of Sweden.[110]

Switzerland

In July 2016, the Canton of Ticino banned face-covering veils.[111]

In September 2018, a ban on face-covering veils was approved with a 67% vote in favour in the canton of St Gallen. The largest Islamic community organisation in Switzerland, the Islamic Central Council, recommended that Muslim women continue to cover their faces.[112]

North America

United States

In 2002, Sultaana Freeman (formerly Sandra Keller, who converted to Islam in 1997 when marrying a Muslim man), sued the U.S. state of Florida for the right to wear a niqab for her driver's license photo.[60] However, a Florida appellate court ruled that there was no violation in the state requiring her to show her face to a camera in a private room with only a female employee to take the picture, in exchange for the privilege of driving. The prevailing view in Florida is currently that hiding one's face on a form of photo identification defeats the purpose of having the picture taken,[60] although 15 other states (including Arkansas, California, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, and Louisiana) have provisions that allow for driver's licenses absent of an identifying photograph in order to accommodate individuals who may have a religious reason to not have a photograph taken.[113] In 2012, a string of armed robberies in Philadelphia were committed by people disguised in traditional Islamic woman's garb; Muslim leaders were concerned that the use of the disguises could put Muslim women in danger of hate crimes and inflame ethnic tensions.[114]

Canada

The niqab is banned in the Canadian province of Quebec in all publicly funded services. One cannot receive public service or provide public service with their faces covered. On October 18, 2017, Bill 62 passed into law after a 66-51 vote in the Quebec National Assembly. The new law is entitled "An Act to foster adherence to State religious neutrality and, in particular, to provide a framework for requests for accommodation on religious grounds in certain bodies". However, regulations regarding the ban's implementation, and religious accommodations, are not expected until July 2018.[115]

On 16 November 2015 the first act of Canada's newly appointed Minister of Justice and Attorney General Jody Wilson-Raybould was to assure women who chose to wear the niqāb during the Oath of Allegiance of their right to do so.[116] In December 2011 then-Citizenship and Immigration Minister Jason Kenney announced a policy directive from the Federal Government under then-Prime Minister Stephen Harper that Muslim women must remove niqābs throughout the citizenship ceremony where they declare their Oath of Allegiance.[117] Zunera Ishaq, a Sunni Muslim woman living in Mississauga, Ontario, challenged and won the niqāb ban in the case of Canada v Ishaq on 5 October 2015. The Federal Court of Appeal decision in her favour was seen by some as "an opportunity to revisit the rules governing the somewhat difficult relationship between law and policy."[118] In October 2015 Harper had appealed the Supreme Court of Canada to take up the case. With the election of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau on 19 October 2015, the niqāb debate was settled as the Liberal government chose to not "politicize the issue any further."[119] Minister Wilson-Raybould, who is the first Indigenous person to be named as Justice Minister, explained as she withdrew Harper's appeal to the Supreme Court, "In all of our policy as a government we will ensure that we respect the values that make us Canadians, those of diversity, inclusion and respect for those fundamental values."[116] The Justice Minister spoke with Zunera by telephone to tell her the news prior to making her official announcement.[116]

Elections Canada, the agency responsible for elections and referenda, stated that Muslim women can cover their faces while voting. The decision was criticized by the Conservative Party of Canada, Bloc Québécois, and Liberal Party of Canada. The New Democrats were not opposed to the decision.[120] The Conservative federal Cabinet had introduced legislation to parliament that would bar citizens from voting if they arrived at polling stations with a veiled face.

The niqāb became an issue in the 2007 election in Quebec after it became public knowledge that women wearing the niqāb were allowed to vote under the same rules as electors who did not present photo identification (ID); namely, by sworn oath in the presence of a third party who could vouch for their identity. The chief electoral officer received complaints that this policy was too accommodating of cultural minorities (a major theme in the election) and thereafter required accompaniment by bodyguards due to threatening telephone calls. All three major Quebec political parties were against the policy, with the Parti Québécois and Action démocratique du Québec vying for position as most opposed. The policy was soon changed to require all voters to show their face, even if they did not carry photo ID. However, Quebec residents who wear the niqāb stated they were not opposed to showing their faces for official purposes, such as voting.[121] Salam Elmenyawi of the Muslim Council of Montreal estimated that only 10 to 15 Muslim voters in the province wear the niqāb and, since their veils have become controversial, most would probably not vote.[122]

In October 2009, the Muslim Canadian Congress called for a ban on burqa and niqāb, saying that they have "no basis in Islam".[123] Spokesperson Farzana Hassan cited public safety issues, such as identity concealment, as well as gender equality, stating that wearing the burqa and niqāb is "a practice that marginalizes women."[123]

In December 2012, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that Muslim women who wear the niqāb must remove it in some cases when testifying in court.[124]

See also

References

- ↑ Manea, Elham (27 August 2017). "Pauline Hanson's Senate stunt shows why we need to confront the ideology behind the burqa". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 24 March 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ↑ Hamad, Ruby (21 April 2017). "The uncomfortable truth about Australian 'diversity'". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ↑ http://www.zombietime.com/mohammed_image_archive/islamic_mo_full/

- 1 2 How to Hijab: Face Veils Modern Muslima and Saraji Umm Zaid Retrieved 16 April 2007. Archived 2 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ See for instance F. R. C. Bagley, "Introduction", in B. Spuler, A History of the Muslim World. The Age of the Caliphs, 1995, X; for a different view T. Dawson, "Propriety, practicality and pleasure : the parameters of women's dress in Byzantium, A.D. 1000-1200", in L. Garland (ed.), Byzantine women: varieties of experience 800-1200, 2006, 41-76.

- ↑ Geography 11.13.9-10.:"Some say that Medeia introduced this kind of dress when she, along with Jason, held dominion in this region, even concealing her face whenever she went out in public in place of the king Archived 21 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine."

- ↑ The Veiling of Virgins Ch. 17. Tertullian writes, "The pagan women of Arabia, who not only cover their head but their whole face, so that they would rather enjoy half the light with one eye free than prostitute the face, will judge you. (Judicabunt vos Arabiae feminae ethnicae quae non caput, sed faciem totam tegunt, ut uno oculo liberato contentae sint dimidiam frui lucem quam totam faciem prostituere)."

- ↑ "Clement of Alexandria, 'Going to Church' Chapter XI, Book 3, Paedagogus". New Advent Fathers. Archived from the original on 16 November 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

Woman and man are to go to church decently attired, with natural step, embracing silence, possessing unfeigned love, pure in body, pure in heart, fit to pray to God. Let the woman observe this, further. Let her be entirely covered, unless she happen to be at home. For that style of dress is grave, and protects from being gazed at. And she will never fall, who puts before her eyes modesty, and her shawl; nor will she invite another to fall into sin by uncovering her face.

- ↑ "Clement of Alexandria, "On Clothe"' Chapter XI, Book 2, Paedagogus". New Advent Fathers. Archived from the original on 9 March 2014. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ↑ Astour, Michael (June 1966). "Tamar the Hieronodule". Journal of Biblical Literature. 85 (2). JSTOR 3265124.

- ↑ 'Prostitution' in Baker's Evangelical Dictionary of Biblical Theology. Baker Academic. ISBN 9780801020759. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ↑ Westenholtz, Joan (July 1989). "Tamar, Qědēšā, Qadištu, and Sacred Prostitution in Mesopotamia". Harvard Theological Review. Cambridge University Press. 82 (3): 245–68. JSTOR 1510077.

- ↑ Lipinski, Edward (January–February 2014). "Cult Prostitution in Ancient Israel?". Biblical Archaeology Review. Biblical Archaeology Society. 40 (1). Archived from the original on 5 July 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ↑ Blomfield, Adrian (5 October 2009). "Egypt bans niqab from schools and colleges". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 8 October 2009. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- ↑ "Islam must be separated from the niqab issue | Jebara | Columnists | Opinion | O". Ottawasun.com. Archived from the original on 7 August 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ "The Hadith Tradition | ReOrienting the Veil". Veil.unc.edu. Archived from the original on 19 April 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ "Covering the face during Hajj or Umrah". Islamweb.net. Archived from the original on 8 November 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ "Azhar Imam Orders Niqab off, Wants Ban". Web.archive.org. 8 October 2009. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ↑ Christian Fraser (10 October 2009). "From our own correspondent, 'No covering up Egypt's niqab row'". BBC News. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ↑ Ozdawah (7 March 2012). "The Niqab and its obligation in the Hanafi madhhab". Seeking Ilm. Archived from the original on 11 May 2009. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ↑ Oza (7 March 2012). "Niqab in Madhhab". Silm. Archived from the original on 12 January 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ↑ Seeking Ilm (7 March 2012). "Shafii stance on women covering their faces". Seeking Ilm. Archived from the original on 7 June 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ↑ Ozdawah (7 March 2012). "The Niqab – Fard, Or Sunnah? (according to the madhaahib)". Ozdawah. Archived from the original on 8 September 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ↑ Yusuf al-Qaradawi, "Is Wearing the Niqāb Obligatory for Women?" Archived 23 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine., SuhaibWebb.com; accessed 1 February 2017.

- ↑ al-Qaraḍāwī, Yūsuf. "Is Wearing the Niqāb Obligatory for Women?". SuhaibWebb.com. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- ↑ IslamQA.info (7 March 2008). "Awrah". IslamQ&A. Archived from the original on 17 June 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ↑ IslamQA.info (7 March 2008). "Ruling on covering the face, with detailed evidence". IslamQ&A. Archived from the original on 29 September 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ↑ "Is it permissible to take off the khimar in front of a blind man?". Islamqa.info. 2006-11-07. Retrieved 2017-02-28.

- ↑ "Women revealing their adornment to men who lack physical desire - Islam web ladies'". Islamweb. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ Queer Spiritual Spaces: Sexuality and Sacred Places, p. 89, Kath Browne, Sally Munt, Andrew K. T. Yip - 2010

- ↑ Meijer, Global Salafism, pg. 66.

- ↑ "The Islamic Modest Dress". Mutahhari. 7 March 2008. Archived from the original on 15 June 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ↑ "Wayback Machine" (PDF). Web.archive.org. 21 October 2004. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ↑ Quran, Surah Azhab verse 30-31

- ↑ "Religions - Islam: Niqab". BBC. Archived from the original on 21 May 2009. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- 1 2 "Why Women Should Wear the Veil". Web.archive.org. 23 February 1999. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ↑

- ↑ "Ruling on covering the face, with detailed evidence". Islamqa.info. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Unveiling the Headscarf Debate, Internationalhumanrightslaw.net; accessed 1 February 2017.

- 1 2 Ismail, Benjamin (1 September 2010). "Ban the Burqa? France Votes Yes". Meforum.org. Archived from the original on 19 February 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ↑ "Burqas Banned, Not Sikh Turbans: French Embassy". Huffingtonpost.in. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- 1 2 "French Full Veil Ban Comes Into Force". Rferl.org. Archived from the original on 7 August 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ↑ Ahmed al-Sayyed (8 October 2009). "Al-Azhar bans "niqab" in classrooms, dormitories". Al Arabiya. Archived from the original on 4 October 2010. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- ↑ Asnad e Kashf e Hijab 24:2

- ↑ El-Guindi, Fadwa, Veil: Modesty, Privacy, and Resistance, Berg, 1999

- ↑ "Women not required to cover faces, hands and feet under Sharia: CII". The Express Tribune. AFP. 20 October 2015. Archived from the original on 20 January 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ↑ Moqtasami (1979), pp. 41-44

- ↑ "Saudi cleric favours one-eye veil". BBC News. 3 October 2008. Archived from the original on 4 October 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ↑ "Syria suspends fully veiled school teachers". Al Arabiya. 29 June 2010. Archived from the original on 2 July 2010. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- ↑ "Syria's Solidarity With Islamists Ends at Home", Nytimes.com, 3 September 2010; retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ↑ "Syria reverses ban on Islamic face veil in schools". Forbes.com. Associated Press. 6 April 2011. Archived from the original on 9 April 2011. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ↑ Ridhwan Al-Saqqaf and Mariam Saleh Aden Bureau (3 October 2008). "Saudi cleric favours one-eye veil". Yemeni Times. Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ↑ Ridhwan Al-Saqqaf and Mariam Saleh Aden Bureau (3 October 2008). "Girls' niqab". Yemeni Times. Archived from the original on 5 October 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ↑ Ridhwan Al-Saqqaf and Mariam Saleh Aden Bureau (3 October 2008). "The niqab through a foreigner's eyes". Yemeni Times. Archived from the original on 17 June 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ↑ Al-Sakkaf, Nadia (17 June 2010). "Renowned activist and press freedom advocate Tawakul Karman to the Yemen Times: "A day will come when all human rights violators pay for what they did to Yemen"". Women Journalists Without Chains. Archived from the original on 30 January 2011. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- ↑ M. J. Gohari (2000). The Taliban: Ascent to Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 108-10.

- ↑ "Dubai 'bearded lady' marriage off". BBC News. 10 February 2010. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ↑ Allen, Peter (11 February 2010). "Ambassador calls for divorce after veil-wearing Muslim bride reveals a beard and crossed eyes". Daily Mail. London, UK. Archived from the original on 30 July 2012.

- ↑ "Man claims fiancee hid beard under niqab". gulfnews. 10 February 2010. Archived from the original on 5 November 2010. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- 1 2 3 Judge: Woman can't cover face on driver's license 10 June 2003. CNN.com; retrieved 13 April 2007.

- ↑ Thorpe, Janet. "SULTAANA LAKIANA MYKE FREEMAN, CASE NO. 2002-CA-2828" (PDF). news.FindLaw.com. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ↑ "SULTAANA LAKIANA MYKE FREEMAN v. DEPARTMENT OF HIGHWAY SAFETY AND MOTOR VEHICLES, Case No. 5D03-2296" (PDF). princeton.edu. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ↑ Hunt, Kate (18 April 2005). "No one wanted to be near me: Student wears burqa throughout winter semester". Echo Online: A Reflection of the English Michigan University Community: The Eastern Echo. Archived from the original on 4 May 2005.

- ↑ Gazzar, Brenda (23 April 2006). "Palestinians Debate Women's Future Under Hamas". Women's eNews. Archived from the original on 5 April 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2007.

- ↑ Cambanis, Thanassis (21 January 2006). "Islamist women redraw Palestinian debate on rights". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 30 May 2006. Retrieved 13 April 2007.

- ↑ "Gaza's deadly guardians". Time Times. 30 September 2007. Archived from the original on 9 September 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ O'Loughlin, Ed (24 January 2006). "The eyes have it: Muslim women win role in Palestinian body politic". The Age. Archived from the original on 23 September 2006. Retrieved 13 April 2007.

- ↑ BBC: "Cameroon bans Islamic face veil after suicide bombings" Archived 17 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine., Bbc.com, 16 July 2015.

- 1 2 "Another African country bans Islamic veil for women over terror attacks", Washingtonpost.com, 18 June 2015.

- ↑ "Cameroon bans face veil after bombings". Bbc.com. 16 July 2015. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ↑ "Chad police: Anyone wearing face veils will be arrested". Al Jazeera English. 12 July 2015. Archived from the original on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ "Chad arrests 62 women for wearing veils after bombings". News24. 16 October 2015. Archived from the original on 24 September 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ "Congo-Brazzaville bans Islamic face veil in public places". BBC News. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ "Congo-Brazzaville bans women from wearing full veil - Security reasons cited as the reason behind the ban, according to an Islamic association" Archived 16 October 2015 at Wikiwix, Aljazeera.com, 3 May 2015

- ↑ Rose Troup Buchanan (2 May 2015). "Republic of Congo bans full-face veils in attempt to prevent religious extremist attacks". The Independent. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ "Morocco 'bans the sale and production of the burka'". BBC News. 10 January 2017. Archived from the original on 31 January 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ↑ "Australia burka armed robbery sparks ban debate". BBC News. 7 May 2010. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ Harriet Agerholm (1 September 2017). "Tajikstan passes law 'to stop Muslim women wearing hijabs'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017.

- ↑ Dutch Muslims condemn burqa ban Archived 11 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. Retrieved 13 April 2007.

- 1 2 "Netherlands plans to ban full-face veil in public places". Reuters.com. 22 May 2017. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2017 – via Reuters.

- ↑ Welt.de: Niederlande verbieten Burkas und Niqabs Archived 29 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine., Welt.de, 29 November 2016.(in German)

- ↑ "Gedeeltelijk verbod gezichtsbedekkende kleding" (in Dutch). Rijksoverheid. 26 June 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ↑ Allen, Peter (19 August 2014). "'Drunk' Belgium diplomat specialising in protocol is arrested for tearing full-face veil off a Qatari princess". The Daily Mail. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015.

- ↑ "Top Europe court upholds ban on full-face veil in Belgium". 11 July 2017. Archived from the original on 13 July 2017. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- ↑ "Denmark is about to ban the burqa".

- ↑ Pilditch, David (9 October 2017). "Denmark burka ban: Scandinavian country set to become latest to ban full-face veils".

- ↑ "Denmark passes ban on niqabs and burkas". BBC News. 31 May 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ↑ "Fra i dag kan Ayesha få en bøde for at gå på gaden: 'Jeg tager aldrig min niqab af'". DR (in Danish). Retrieved 2018-08-03.

- 1 2 "Joining other European countries, Denmark bans full-face veil in public - France 24". France 24. 2018-05-31. Retrieved 2018-08-03.

- ↑ "Hestehoveder og niqaber: Demonstranter dækker ansigtet til i protest mod forbud". DR (in Danish). Retrieved 2018-08-03.

- 1 2 "Første kvinde er sigtet for at overtræde tildækningsforbud". DR (in Danish). Retrieved 2018-08-04.

- ↑ 'No discrimination' in veil row Archived 29 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. 19 October 2006

- ↑ BBC: "Robber wearing niqab targets Birmingham Lloyds TSB bank - A man wearing a niqab face veil has robbed a security guard outside a bank in Birmingham" Archived 17 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine., Bbc.co.uk, 6 May 2010.

- ↑ "Police stop Muslim woman wearing veil in Italy". BBC News. 3 May 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- 1 2 "Tromsø-professor forbyr niqab i forelesninger". Vg.no. Archived from the original on 23 March 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ↑ kontor, Statsministerens (27 February 2010). "Ikke behov for nye forbud". Regjeringen.no. Archived from the original on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ↑ Bjerkeland, Øystein (10 November 2014). "Forbudt med niqab i skolen". Rbnett.bo. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ↑ "Flertall for nikab-forbud". Nrk.no. Archived from the original on 19 September 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ↑ "Norway proposes ban on full-face veils in schools". dailymail.co.uk. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ↑ "Erna Solberg: – Du får ikke jobb hos meg hvis du har nikab på". NRK. 18 October 2016. Archived from the original on 23 October 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ↑ "Norway bans burqa and niqab in schools". 2018-06-06. Retrieved 2018-06-10.

- ↑ "Nå blir det forbudt med nikab i norske skoler". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian Bokmål). Retrieved 2018-06-10.

- ↑ "Islamic face veil to be banned in Latvia despite being worn by just three women in entire country". Independent.co.uk. 21 April 2016. Archived from the original on 21 January 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ↑ Bulgaria the latest European country to ban the burqa and niqab in public places Archived 5 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine., Smh.com.au: accessed 5 December 2016.

- ↑ "Integration: Österreich stellt Tragen von Burka und Nikab unter Strafe". Welt.de. 16 May 2017. Archived from the original on 8 February 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2018 – via www.welt.de.

- ↑ Nachrichten, n-tv. "Bundestag beschließt Sicherheitspaket". n-tv.de. Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ↑ "CSU-Verkehrsminister Alexander Dobrindt will offenbar Burka-Verbot im Auto". waz.de. Archived from the original on 17 August 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ↑ WELT (7 July 2017). "Burka-Verbot: Bayern verbietet Gesichtsschleier in vielen Bereichen". Welt.de. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2018 – via www.welt.de.

- ↑ "Burka-Streit: Niedersachsen verbietet Vollverschleierung an Schulen - WELT". DIE WELT. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ↑ "Mångfaldsbarometern 2012: Extremt negativa attityder permanentas och riskerar växa - Uppsala universitet". uppsalauniversitet.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 2018-07-12.

Svaren innebär att motståndet i Sverige mot Burka och Niqab är kompakt, 84,4 respektive 81,6 procent anser att de är ganska eller helt oacceptabla. Motståndet har åter ökat något.

- ↑ "Muslims face fines up to £8,000 for wearing burkas in Switzerland". The Independent. 8 July 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ↑ Editorial, Reuters. "Swiss canton becomes second to ban burqas in public". U.S. Retrieved 2018-09-24.

- ↑ "ACLU of Florida". Web.archive.org. 30 May 2004. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ↑ Michael Muskal (25 April 2012). "Islamic attire used as disguise in Philadelphia bank robberies - latimes". Articles.latimes.com. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ "Answers to some key questions on Quebec's face-covering law - CBC News". cbc.ca. Archived from the original on 20 April 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- 1 2 3 Mas, Susana; Crawford, Alison (16 November 2015). "Justin Trudeau's government drops controversial niqab appeal: Zunera Ishaq says move is a 'very good gesture from the government in supporting minorities'". CBC. Archived from the original on 25 December 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ↑ "Muslim women must show faces when taking citizenship oath". Globe & Mail. 12 December 2011. Archived from the original on 8 May 2014.

- ↑ Fluker, Shaun (28 September 2015). "The Niqab, the Oath of Citizenship, and the Blurry Line between Law and Policy" (PDF). The University of Calgary Faculty of Law Blog. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ↑ "Guarding against "us" and "them"". Tri City News. 7 December 2015. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ↑ LeBlanc, Daniel. "Elections Canada blasted for allowing Muslim women to vote with faces covered" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine., The Globe and Mail; accessed 1 February 2017.

- ↑ "Muslim women will have to lift veils to vote in Quebec election". CBC News. 23 March 2007. Archived from the original on 25 August 2007.

- ↑ "Veiled threats". Web.archive.org. 11 May 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- 1 2 "Muslim group calls for burka ban". CBC News. 8 October 2009. Archived from the original on 11 October 2009. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- ↑ "Niqab in court OK in some cases". CTV. 20 December 2012. Archived from the original on 20 December 2012.

Further reading

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to niqab. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: niqab |

- Religion and Ethics - Beliefs: Niqab, British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), 13 April 2007.

- Modesty Gowns for Female Patients, BBC, 5 September 2006

- The Veil and the British Male Elite, Social Science Research Network (SSRN)

- Niqab is Not Obligatory

- The Last Straw!