White tie

| Part of a series on |

| Western dress codes and corresponding attires |

|---|

|

|

Supplementary

|

|

Legend: |

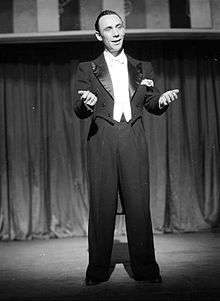

White tie, also called full evening dress or a dress suit, is the most formal evening dress code in Western high fashion. For men, it consists of a black dress tailcoat worn over a white starched shirt, marcella waistcoat and the eponymous white bow tie worn around a detachable collar. High-waisted black trousers and patent leather shoes complete the outfit, although decorations can be worn and a top hat and white scarf are acceptable as accessories. Women wear full length evening or ball gown and, optionally, jewellery, tiaras, a small bag and evening gloves.

The dress code's origins can be traced to the end of the 18th century, when high society men began abandoning their breeches, lacy shirts and richly decorated evening coats for more austere tailcoats in dark colours, a look inspired by the country gentleman. Fashionable dandies like Beau Brummell popularised a minimalist style in the Regency era, tending to favour dark blue or black tailcoats, often with trousers instead of breeches, and white shirts, waistcoats and cravats. By the 1840s the minimalist black and white combination had become the standard evening wear for upper class men. Despite the emergence of the dinner jacket (or tuxedo) as a less formal and more comfortable alternative in the 1880s, full evening dress remained the staple. At the turn of the 20th century, white became the only colour of waistcoats and ties worn with full evening dress, contrasting with black ties and waistcoats with the dinner jacket, an ensemble which became known as black tie.

From the 1920s onward black tie slowly replaced white tie as the default evening wear for important events, so that by the 21st century white tie had become rare. White tie nowadays tends to be reserved for special ceremonies—especially state dinners—and a very select group of social events such as the Al Smith Memorial Dinner in New York, the Commemoration balls at Oxford University, certain May Balls at Cambridge University, the June Ball at Durham University, the Christmas ball at Buckingham Palace, dinners of certain American hereditary societies, and very formal weddings. The Vienna Opera Ball and the Nobel Prize ceremony are white tie events, and some European universities retain it as the dress code for doctoral conferment ceremonies.

Description

Traditions

According to the British etiquette guide Debrett's, the central components of full evening dress for men are a white marcella shirt with a detachable wing collar and single cuffs, fastened with studs and cufflinks; the eponymous white marcella bow tie is worn around the collar, while a low-cut marcella waistcoat is worn over the shirt. Over this is worn a black single-breasted barathea wool or ultrafine herringbone tailcoat with silk peak lapels. The trousers have double-braiding down the outside of both legs, while the correct shoes are patent leather or highly polished black dress shoes. Although a white scarf remains popular in winter, the traditional white gloves, top hats, canes and cloaks are now rare. Women wear a full-length evening dress, with the option of jewellery, a tiara, a pashmina, coat or wrap. Long gloves are not compulsory.[1]

The waistcoat should not be visible below the front of the tailcoat, which necessitates a high waistline and (often) braces for the trousers. As one style writer for GQ magazine summarises "The simple rule of thumb is that you should only ever see black and white not black, white and black again".[2][3] While Debrett's accepts double cuffs for shirts worn with white tie,[1] some tailors and merchant suggest that single, linked cuffs are the most traditional and formal variation acceptable under the dress code.[4] Decorations may also be worn and, unlike Debrett's, Cambridge University's Varsity student newspaper suggests a top hat, opera cloak and silver-topped cane are acceptable accessories.[5] Some invitations to white-tie events, like the last published edition of the British Lord Chamberlain's Guide to Dress at Court, state that national costume or national dress may be substituted for white tie.[6][7]

Other variations

Military dress

Prior to World War II formal style of military dress was generally restricted to the British, British Empire and United States armed forces; although the French, Imperial German, Swedish and other navies had adopted their own versions of mess dress during the late nineteenth century, influenced by the Royal Navy.[8]

In the US Army, evening mess uniform, in either blue or white, is the appropriate military uniform for white-tie occasions.[9] The blue mess and white mess uniforms are black-tie equivalents, although the Army Service Uniform with bow tie are accepted, especially for non-commissioned officers and newly commissioned officers. For white-tie occasions, of which there are almost none in the United States outside the national capital region for US Army, an officer must wear a wing-collar shirt with white tie and white vest. For black-tie occasions, officers must wear a turndown collar with black tie and black cummerbund. The only outer coat prescribed for both black- and white-tie events is the army blue cape with branch color lining.[10]

Clerical dress

Certain clergymen wear, in place of white-tie outfits, a cassock with ferraiolone, which is a light-weight ankle-length cape intended to be worn indoors. The colour and fabric of the ferraiolone is determined by the rank of the cleric and can be scarlet watered silk, purple silk, black silk or black wool. For outerwear the black cape (cappa nigra), also known as a choir cape (cappa choralis), is most traditional. It is a long black woollen cloak fastened with a clasp at the neck and often has a hood. Cardinals and bishops may also wear a black plush hat or, less formally, a biretta. In practice, the cassock and especially the ferraiolone have become much less common and no particular formal attire has appeared to replace them. The most formal alternative is a clerical waistcoat incorporating a Roman collar (a rabat) worn with a collarless French cuff shirt and a black suit, although this is closer to "black-tie" than white-tie. Historically, clerics in the Church of England would wear a knee-length cassock called an apron, accompanied by a tailcoat with silk facings but no lapels, for a white tie occasion. In modern times this is rarely seen. However, if worn, the knee-length cassock is now replaced with normal dress trousers.

19th century: origins and development

Throughout the Early Modern period, western European male courtiers and aristocrats donned elaborate clothing at ceremonies and dinners: coats (often richly decorated), frilly and lacy shirts and breeches formed the backbone of their most formal attire. As the 18th century drew to a close, high society began adopting more austere clothing which drew inspiration from the dark hues and simpler designs adopted by country gentlemen.[11] By the end of the 18th century, two forms of tail coat were in common use by upper class men in Britain and continental Europe: the more formal dress coat (cut away horizontally at the front) and the less formal morning coat, which curved back from the front to the tails. From around 1815, a knee-length garment called the frock coat became increasingly popular and was eventually established, along with the morning coat, as smart daywear in Victorian England. The dress coat, meanwhile, became reserved for wear in the evening.[12] The dandy Beau Brummell adopted a minimalistic approach to evening wear—a white waistcoat, dark blue tailcoat, black pantaloons and striped stockings.[13] Although Brummell felt black an ugly colour for evening dress coats, it was adopted by other dandies, like Charles Baudelaire, and black and white had become the standard colours by the 1840s.[14][15]

Over the course of the 19th century, the monotone colour scheme became a codified standard for evening events after 6 p.m. in upper class circles.[11] The styles evolved and evening dress consisted of a black dress coat and trousers, white or black waistcoat, and a bow tie by the 1870s. The dinner jacket (tuxedo) emerged as a less formal and more comfortable alternative to full evening dress in the 1880s and, by the early 20th century, full evening dress meant wearing a white waistcoat and tie with a black tailcoat and trousers, the tuxedo incorporated a black bow tie and waistcoat: white tie had become distinct from black tie.[16] Despite its growing popularity, the dinner jacket remained the reserve of family dinners and gentlemen's clubs during the late Victorian period.[11]

20th century

By the turn of the 20th century, full evening dress consisted of a black tailcoat made of heavy fabric weighing 16-18 oz per yard. Its lapels were medium width and the white shirt worn beneath it had a heavily starched, stiff front, fastened with pearl or black studs and either a winged collar or a type called a "poke", consisting of a high band with a slight curve at the front.[17] After World War I, the dinner jacket became more popular, especially in the US, and informal variations sprang up, like the soft, turn-down collar shirt and later the double-breasted jacket;[18] relaxing social norms in Jazz Age America meant white tie was replaced by black tie as the default evening wear for young men, especially at nightclubs.[11] According to The Delineator, the years after World War I saw white tie "almost abandoned".[19] But it did still have a place: the American etiquette writer Emily Post stated in 1922 that "A gentleman must always be in full dress, tail coat, white waistcoat, white tie and white gloves" when at the opera, yet she called the tuxedo "essential" for any gentleman, writing that "It is worn every evening and nearly everywhere, whereas the tail coat is necessary only at balls, formal dinners, and in a box at the opera."[20]

It also continued to evolve. White tie was worn with slim-cut trousers in the early 1920s; by 1926, wide-lapelled tailcoats and double-breasted waistcoats were in vogue.[21] The Duke of Windsor (then Prince of Wales and later Edward VIII) wore a midnight blue tailcoat, trousers and waistcoat in the 1920s and 1930s both to "soften" the contrast between black and white and allow for photographs to depict the nuances of his tailoring.[22] The late 1920s and 1930s witnessed a resurgence in the dress code's popularity,[19][23] but by 1953, one etiquette writer stressed that "The modern trend is to wear 'tails' only for the most formal and ceremonious functions, such as important formal dinners, balls, elaborate evening weddings, and opening night at the opera".[24]

The last president to have worn white tie at a United States presidential inauguration was President John F. Kennedy in 1961, who wore morning dress for his inauguration, and a white tie ensemble for his inauguration ball.

21st century

White tie is rarely worn in the early 21st century.[1] Nevertheless, it survives as the formal dress code for royal ceremonies, debutante balls, and a select group of other social events in some countries. The male form has also been adopted for some formal weddings.[1]

Notable international recurrent white tie events include the Nobel Prize ceremony in Sweden,[25] and the Vienna Opera Ball in Austria.[26]

In Scandinavia and the Netherlands, white tie is the traditional attire for doctoral conferments and is prescribed at some Swedish and Finnish universities, where it is worn with a top hat variant called a doctoral hat.[27][28][29][30][31]

White tie is only required when the invitation specifically requests it[32][33] but a considerate host will usually request 'white or black tie' because of the potential difficulty faced by some guests in obtaining proper white tie attire.[33]

United Kingdom

In Britain, it is worn at some state dinners[34][35] and certain May and commemoration balls at Oxford and Cambridge universities as well as University College Durham and St Andrews.[36][37][38] It was the dress code for the Lord Mayor of London's Mansion House dinner until 1996.[39] White tie is also rarely seen as part of some elite UK public (private) schools' uniform, such as Harrow School, where the Head Boy is allowed to wear white tie to special events.

United States

A few state dinners at the White House apply white tie, including the one held for Queen Elizabeth II in 2007.[40] Other notable examples include the Gridiron Club Dinner in Washington, D.C., the Alfred E. Smith Memorial Foundation Dinner in New York City, and a few debutante balls such as the International Debutante Ball in New York City, and the Veiled Prophet Ball in St. Louis.

When the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Costume Institute Gala in New York City announced a white tie dress code in 2014, a number of media outlets pointed out the difficulty and expense of obtaining traditional white tie, even for the celebrity guests.[41][42]

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 "White Tie", Debrett's, retrieved 28 September 2015

- ↑ Johnston, Robert. "Attire to suit the occasion". GQ. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ↑ "Evening Tailcoat". Ede & Ravenscroft. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ↑ "White tie dress code". Savvy Row. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ↑ Sharpe, James (9 May 2011). "Fix Up, Look Sharpe: Dress codes". Varsity. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ↑ Canadian Heritage (1985). "Dress". "Diplomatic and Consular Relations and Protocol" External Affairs. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- ↑ Nobleprize.org. "The Dress Code at the Nobel Banquet: What to wear?".

- ↑ Knötel, Knötel & Sieg (1980), pp. 442–445.

- ↑ http://www.ncoguide.com/files/da-pam-670_1.pdf

- ↑ http://www.ncoguide.com/files/da-pam-670_1.pdf

- 1 2 3 4 Marshall, Peter. "A Field Guide to Tuxedos". Slate. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ↑ Jenkins 2003, pp. 886

- ↑ Carter 2011

- ↑ Williams 1982, p. 122

- ↑ Jenkins 2003, p. 887

- ↑ Jenkins 2003, pp. 888, 890

- ↑ Schoeffler 1973, p. 166

- ↑ Schoeffler 1973, p. 168

- 1 2 The Delineator, vol. 128 (January 1936), p. 57

- ↑ Emily Post (1922). Etiquette in Society, in Business, in Politics and at Home. New York and London: Funk and Wagnalls co. chap. vi, xxxiv

- ↑ Schoeffler 1973, pp. 169-170

- ↑ "Evening suit". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ↑ Schoeffler 1973, p. 170

- ↑ Lillian Eichler Watson (1953). New Standard Book of Etiquette. New York: Garden Publishing Company. p. 358

- ↑ "The Dress Code at the Nobel Banquet". Nobel Prize. Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ↑ Blake, Matt (28 February 2014). "A fight at the Opera Ball! White tie-clad gents trade punches at Vienna's premier social event, attended by Kim Kardashian". Daily Mail. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ↑ "Degree conferment celebrations for new PhDs". Uppsala University. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ↑ "Degree Ceremonies 2006". University of Vaasa. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ↑ Miller, Beth (31 August 2010). "A sword, a hat and three unforgettable days in Helsinki". Washington University in St Louis. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ↑ Ditzhuyzen, Reinildis van (2013). De Dikke Ditz: Hoe hoort het eigenlijk? (in Dutch). Haarlem: H. J. W. Becht. p. 292. ISBN 978-90-230-1381-5.

- ↑ http://promootio.aalto.fi/fi/history/2014/pukeutuminen/

- ↑ Post, Peggy; Post, Lizzie; Post Sennig, Daniel (2011). Emily Post's Etiquette. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. pp. 328–329. ISBN 978-0-06-174023-7.

- 1 2 Wyse, Elizabeth (2015). Debrett's Handbook. London: Debrett's Limited. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-9929348-1-1.

- ↑ "President Obama hosts star-studded farewell dinner". BBC News. 25 May 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ↑ Gammell, Caroline (31 October 2007). "Protests, pomp and a PM in white tie". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ↑ "Magdalen Commemoration Ball cancelled". Cherwell. 12 March 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ↑ Shan, Fred (1 April 2014). "Mr Shan Menswear: on White Tie". The Oxford Student. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ↑ http://thetab.com/uk/stand/2014/11/14/review-white-tie-reeling-ball-11659

- ↑ Willcock, John (6 June 1996). "A black day for white tie at the Lord Mayor's banquet". The Independent. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ↑ Stolberg, Sheryl Gay (8 May 2007). "A White-Tie Dinner for Queen's White House Visit". New York Times. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ↑ Trebay, Guy (23 April 2014). "At the Met Gala, a Strict Dress Code". New York Times. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ↑ Rothman, Lily (5 May 2014). "The Met Ball Is White Tie This Year—But What Does That Even Mean?". Time. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

Bibliography

- Philip Carter (January 2011). "Brummell, George Bryan (Beau Brummell) (1778–1840)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, online ed. (subscription or UK public library membership required). Retrieved 28 September 2015. DOI 10.1093/ref:odnb/3771

- D. T. Jenkins (2003). Cambridge History of Western Textiles, vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521341073

- O. E. Schoeffler (1973). Esquire's encyclopedia of 20th century men's fashions. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill ISBN 9780070554801

- Rosalind H. Williams (1982). Dream Worlds: Mass Consumption in Late Nineteenth-century France. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520043558

External links

![]()