Chador

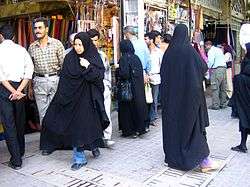

A chādor (Persian: چادر), also variously spelled in English as chadah, chad(d)ar, chader, chud(d)ah, chadur and naturalized as /tʃʌdə(ɹ)/ is an outer garment or open cloak worn by some women in Iran, Iraq and some other countries under the Persianate cultural sphere as well as predominantly Shia areas i.e. Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Pakistan, India, Kuwait, Lebanon, Syria, Tajikistan and Turkey, in public spaces or outdoors. A chador is a full-body-length semicircle of fabric that is open down the front. This cloth is tossed over the woman's or girl's head, but then she holds it closed in the front. The chador has no hand openings, or any buttons, clasps, etc., but rather it is held closed by her hands or tucked under the wearer's arms.

Before the 1978–79 Iranian Revolution, black chadors were reserved for funerals and periods of mourning. Light, printed fabrics were the norm for everyday wear. Currently, the majority of Iranian women who wear the chador use the black version outside and reserve light-coloured chadors for indoor use.

Historical background

Ancient and early Islamic times

Fadwa El Guindi locates the origin of the veil in ancient Mesopotamia, where "wives and daughters of high-ranking men of the nobility had to veil".[1] The veil marked class status, and this dress code was regulated by sumptuary laws.

One of the first representation of a chador is found on Ergili sculptures and the "Satrap sarcophagus" from Persian Anatolia.[2] Bruhn/Tilke, in their 1941 A Pictorial History of Costume, do show a drawing, said to be copied from an Achaemenid relief of the 5th century BC, of a woman with her lower face hidden by a long cloth wrapped around her head.[3] Achaemenid Iranian women in art were mostly veiled.[2] The earliest written record of chador can be found in Pahlavi scripts from the 6th century, as a female head dress worn by Zoroastrian women.[4]

It is likely that the custom of veiling continued through the Seleucid, Parthian, and Sassanid periods. Veiling was not limited to noble women but was practised also by the Persian kings.[4] Upper-class Greek and Byzantine women were also secluded from the public gaze. European visitors of the 18th and 19th centuries have left pictorial records of women wearing the chador and the long white veil.

Pahlavi dynasty

The 20th century Pahlavi ruler Reza Shah banned the chador and all hijab in 1936, as incompatible with his modernizing ambitions.[5] According to Mir-Hosseini as cited by El Guindi, "the police were arresting women who wore the veil and forcibly removing it". This policy outraged the Shi'a clerics, and ordinary men and women, to whom "appearing in public without their cover was tantamount to nakedness". However, she continues, "this move was welcomed by Westernized and upperclass men and women, who saw it in liberal terms as a first step in granting women their rights".[6]

Eventually rules of dress code were relaxed, and after Reza Shah's abdication in 1941 the compulsory element in the policy of unveiling was abandoned, though the policy remained intact throughout the Pahlavi era. According to Mir-Hosseini, 'between 1941 and 1979 wearing hejab [hijab] was no longer an offence, but it was a real hindrance to climbing the social ladder, a badge of backwardness and a marker of class. A headscarf, let alone the chador, prejudiced the chances of advancement in work and society not only of working women but also of men, who were increasingly expected to appear with their wives at social functions. Fashionable hotels and restaurants sometimes even refused to admit women with chador, schools and universities actively discouraged the chador, although the headscarf was tolerated. It was common to see girls from traditional families, who had to leave home with the chador, arriving at school without it and then putting it on again on the way home'.[7]

Iranian Revolution

In April 1980, during the Iranian Cultural Revolution, it was decided that women in government offices and educational institutions would observe the veil.[8] In 1983, a dispute regarding the veiling broke out, and public conflict was motivated by the definition of veiling and its scale (so-called "bad hijab" issue), sometimes followed even by clashes against those who were perceived to wear improper clothing.[8] Government felt obligated to deal with this situation, so on 26 July 1984 Tehran’s public prosecutor issued a statement and announced that stricter dress-code is supposed to be observed in public places such as institutions, theaters, clubs, hotels, motels and restaurants, while in the other places it should follow the pattern of the overwhelming majority of people.[8] Stricter veiling implies both chador and more loosely khimar-type headscarf along with overcoat.

Usage

Before the 1978–79 Iranian Revolution, black chadors were reserved for funerals and periods of mourning. Light, printed fabrics were the norm for everyday wear. Currently, the majority of women who wear the chador reserve the usage of light-colored chadors for around the house or for prayers. Most women who still go outside in urban areas in a light colored chador are elderly women of rural backgrounds. During the reign of the Shah of Iran, such traditional clothing was largely discarded by the wealthier urban upper-class women in favor of modernity for western clothing, although women in small towns and villages continued to wear the chador. Traditionally a light coloured or printed chador was worn with a headscarf (rousari), a blouse (pirahan), and a long skirt (daaman); or else a blouse and skirt or dress over pants (shalvar), and these styles continue to be worn by many rural Iranian women, in particular by older women.

On the other hand, in Iran the chador does not require the wearing of a veil. Inside the home, particularly for urban women, both the chador and the veil have been discarded and there women and teenagers wore cooler and lighter garments; while in modern times, rural women continue to wear a light-weight printed chador inside the home over their clothing during their daily activities. The chador is worn by some Iranian women regardless of whether they are Sunni or Shia, but is considered traditional to Persian Iranians with Iranians of other backgrounds wearing the chador or other traditional forms of attire. For example, Arab Iranian women in Western and Southern Iran retain their Overhead Abaya which is similar to the overhead Abaya worn in Iraq, Kuwait and Bahrain.

See also

References

- ↑ El Guindi, Fadwa (1999), Veil: Modesty, Privacy, and Resistance, Oxford/New York: Berg, p. 16.

- 1 2 CLOTHING ii. In the Median and Achaemenid periods at Encyclopædia Iranica

- ↑ Bruhn, Wolfgang, and Tilke, Max (1955), Kostümwerk, Tübingen: Ernst Wasmuth, p. 13, plate 10.

- 1 2 ČĀDOR (2) at Encyclopædia Iranica

- ↑ mshabani (10 December 2015). "More veils lift as topic loses political punch in Iran".

- ↑ El Guindi, Fadwa (1999), Veil: Modesty, Privacy, and Resistance, Oxford/New York: Berg, p. 174.

- ↑ El Guindi, Fadwa (1999), Veil: Modesty, Privacy, and Resistance, Oxford/New York: Berg, pp. 174–175.

- 1 2 3 Ramezani, Reza (2010). Hijab dar Iran az Enqelab-e Eslami ta payan Jang-e Tahmili [Hijab in Iran from the Islamic Revolution to the end of the Imposed war] (Persian), Faslnamah-e Takhassusi-ye Banuvan-e Shi’ah [Quarterly Journal of Shiite Women], Qom: Muassasah-e Shi’ah Shinasi, ISSN 1735-4730

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chador. |

- Briant, Pierre (2002), From Cyrus to Alexander, Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns

- Bruhn, Wolfgang, and Tilke, Max (1973), A Pictorial History of Costume, original published as Kostümwerk, 1955, Tübingen: Ernst Wasmuth

- El Guindi, Fadwa (1999), Veil: Modesty, Privacy, and Resistance, Oxford/New York: Berg

- Mir-Hosseini, Ziba (1996), "Stretching The Limits: A Feminist Reading of the Shari'a in Post-Khomeini Iran," in Mai Yamani (ed.), Feminism and Islam: Legal and Literary Perspectives, pp. 285–319. New York: New York University Press