Moro people

Three Moro women in Jolo, Sulu, c. 1900s. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 10.7 million (2012)[1] [2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei | |

| Languages | |

|

English, Filipino Maguindanao, Maranao, Tausug, Arabic, Yakan, Zamboangueño, Cebuano, Malay, Urdu and other Philippine languages | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam[3] |

The Moro are the Muslim population of the Philippines, forming the largest non-Catholic[4] group in the country and comprising about 11% (as of the year 2012) of the total Philippine population.[1] [5] Most Moros are followers of Sunni Islam of the Shafi'i madh'hab.

The Bangsamoro people mostly live in Mindanao, Sulu and Palawan. Due to continuous migration, their communities can be found in most big cities of the country, including Manila, Cebu and Davao. Some moros have emigrated to Malaysia, Indonesia and Brunei in the late 20th century due to the Moro conflict in Mindanao. Newer communities can be found today in Kota Kinabalu, Sandakan, Semporna in neighbouring Sabah, Malaysia,[6] North Kalimantan in Indonesia, as well in Bandar Seri Begawan of Brunei.

Etymology

The recently coined term Bangsamoro, derived from the old Malay word "bangsa", meaning "race" or "nation" with the "Moro" as "people", is now used to describe both the Filipino Muslims and their homeland. The term Bangsamoro carries the aspiration of the Filipino Muslims to have an Islamic (Moro) country or state (bangsa).

The word Moro itself was a exonym which had been used before in the 16th century by Spanish colonisers in reference to a Muslim group of "Moors", which originating from "Mauru", a Latin word that referred to the inhabitants of the ancient Roman province of Mauritania in northwest Africa, which today comprises the modern Muslim states of Algeria, Mauritania and Morocco.[7] With the rise of Mauritania as part of the Muslim Umayyad Caliphate, Muslim armies conquered and ruled much of the Iberian Peninsula from 711 to 1492, for about a total of 781 years in which the term was revived when the Christian-majority Spanish became involved in a war with them and started to call the Muslims as "Moors".

The term was then used again by the Spanish when they arriving in the Philippine archipelago and found a similar Muslim community who rebelled against them.[7] Despite opposition from the modern Muslim community in the Philippines who objected to the term's origin by Spanish colonialist, the name has evolved to become seen as a unitary force especially by the Philippine government. Marvic Leonen, who was the Chief Peace Negotiator for Philippine government with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, has said:[8]

There is Bangsamoro, the place; there is Bangsamoro, the identity.

— Marvic Leonen, Press briefing, October 8, 2012

In 1898 via the treaty of Paris the Philippines was turned over to the United States of America. The Americans took over the Philippines in 1898. Not only in part but the entire Archipelago. From Batanes to Tawi-Tawi. Prior to the signing, this Cable message from Pres. McKinley on Nov. 25, 1898 was very explicit: "... to accept merely Luzon, leaving the rest of the islands subject to Spanish rule, or to be the subject of future contention, cannot be justified on political, commercial, or humanitarian grounds. The cessation must be the whole archipelago or none. The latter is wholly inadmissible, and the former must therefore be required." This however, did not settle well with the Muslims(Moros), they fought and are still continuing to fight to take back what was once conquered by them.

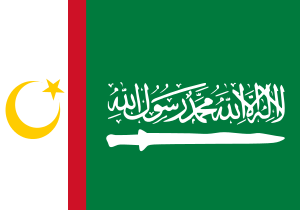

It was later adopted as a name for separatist organisations such as the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), Rashid Lucman's Bangsa Moro Liberation Organisation (BMLO) as well the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF).[9]

The Framework Agreement on the Bangsamoro recognises "Bangsamoro" as an identity and calls for the creation of a new autonomous political entity called Bangsamoro.[10] The native Moro Communities of Mindanao and Sulu are termed considered as Filipino Muslim by the Philippine government.

Ethnic divisions

Fourteen Philippine ethnic groups also referred to as indigenous peoples are as follows:

Society

Region

(ARMM).

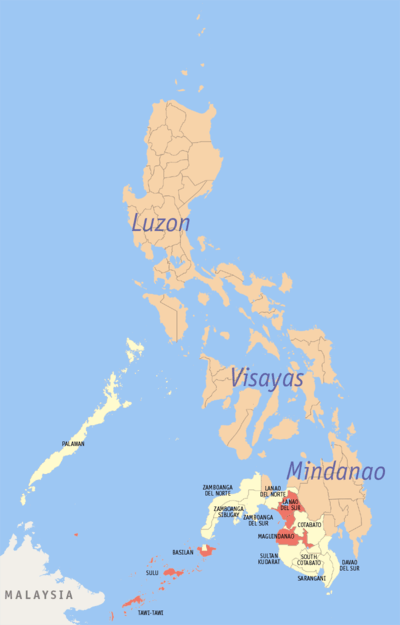

Historical extent of Moro populations and governance.

The majority of the Moro people historically reside in the area they now call the Bangsamoro region which was commonly called Muslim Mindanao. That land is located in the provinces of Basilan, Cotabato, Compostela Valley, Davao del Sur, Lanao del Norte, Lanao del Sur, Maguindanao, Palawan, Sarangani, South Cotabato, Sultan Kudarat and Sulu, Tawi-Tawi. It includes the cities of Cotabato, Dapitan, Dipolog, General Santos, Iligan, Marawi. The eastern part of a territory of the former British protectorate in North Borneo (now in the eastern Sabah), which have since became part of the federation of Malaysia, is also claimed by the Moro National Liberation Front for the proposed state of Bangsamoro Republik. However, the idea has failed since the MNLF founding leader Misuari self-exiled himself after clashing with the government in 2013 in Zamboanga City, as he protested the further unilateral changes by the government on the mutually signed 1996 Final Peace Agreement. Misuari was labelled as a "terrorist" during the siege.[11][12][13]

On 5 August 2008, after nearly 10 years of negotiation, with all Thebes's associated international bodies all ready to witness a supposed historic event, an attempt by the Philippine government's Peace Negotiating Panel to sign a Memorandum of Agreement on Ancestral Domain with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front through a petition by Settler politicians in Mindanao like Governor Manny Pinol and Governor Lobregat, was then declared unconstitutional by the Philippine Supreme Court.[14] Conflict immediately broke out on the ground following the decision, with nearly half a million people displaced and hundreds killed.[14] Observers now concur that two Moro commanders — Kumander Umbra Kato and Kumander Bravo — did launch attacks in Lanao del Norte and North Cotabato as a response to the non signing that has shaken the peace process in the region.

The Framework Agreement on the Bangsamoro defines the Bangsamoro to be "[t]hose who at the time of conquest and colonisation were considered natives or original inhabitants of Mindanao and the Sulu archipelago and its adjacent islands including Palawan, and their descendants whether of mixed or of full blood".[10] This definition of the moro people by the bangsamoro is purely owned by the bangsamoro and not fully accepted by the people of Mindanao or the Philippines. Moro by definition still means Muslim who are still the minority population of Mindanao.

Culture

Moro culture is very Malay-influenced. The Bangsamoro share similarities with the Malay people of Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei, Singapore and southern Thailand, while being distinct from them. The Bangsamoro cultures represent the only living examples of the larger historic lowland cultures of the northern and central Philippines who were once also culturally, and in some cases religiously, similar to modern Bangsamoro ethnicities, prior to the gradual Spanish colonization of the archipelago between the 16th-18th centuries. The precolonial Tagalogs, Kapampangan or Visayan, are seen as being culturally similar to the Moro, although in the case of the Visayan people, they were more Hindu-Buddhist influenced instead (see Rajahnate of Cebu)

Islam is the most dominant influence on the Moro cultures since the era of the Sultanate of Maguindanao and Sulu. Large and small mosques can be found all over the region. In accordance with Islamic Law, alcohol and fornication are prohibited. Pork and pork byproducts are not permissible. Another practice is fasting during Ramadan and providing charity for the poor. The Hajj is also a major requirement as it is one of the five pillars of Islam. Moro women cover themselves using a veil (tudong) just as in Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei, Singapore and southern Thailand. Moro men, especially the elderly, can always be seen wearing a black Muslim skull cap called the songkok or the white one called the taqiyah. Differentiating from their Malay relatives in neighbouring countries, the only main problems associated with Moro groups is that they are not always united and lack a sense of solidarity.[15] Each Moro community are proud of their prowess and wealth as well as with their ethnic tradition, culture and identity.

Music

The culture of the Moro revolves around the music of the kulintang, a type of gong instrument, akin to the drum instrument, yet wholly made of bronze or brass found in the southern Philippines. This creates a unique sound that varies in the speed it is hit which includes the Binalig,[16] Tagonggo and the Kapanirong plus others more also normally heard in Malaysia, Indonesia and Brunei.

Ethnic groups

There are at least thirteen ethnic groups comprising the Indigenous Peoples of the Philippines;[7] all descended from the same Austronesian people (Malayo-Polynesian) that migrated from Taiwan and populated the regions of the Philippines, Southeast Asia, the Pacific islands and Madagascar. Three of these groups make up the majority of these tribes. They are the Maguindanaon of North Cotabato, Sultan Kudarat and Maguindanao provinces, the Maranao of the Lanao provinces and the Tausūg of the Sulu Archipelago. Smaller groups include the Banguingui, Samal and the Bajau of the Sulu Archipelago; the Yakan of Basilan and Zamboanga del Sur, the Illanun of Lanao provinces and Davao and Sangir of Davao, the Molbog of southern Palawan and the Jama Mapuns of Cagayan de Tawi-Tawi Island. These indigenous people from the south mostly converted to the religion of Islam making them Muslims or Moros, some of them converted over to Christianity and other religions.

Languages

The Indigenous people are mostly speakers of a variety of Austronesian languages. The most-spoken native languages of the Indigenous peoples of Mindanao are Maguindanaon, Tausūg and Maranao. The Maguindanao language is spoken in the Maguindanao Province, the Maranao language is predominant in the Lanao region, and is the majority spoken in Lanao del Sur and the Tausug language is spoken in the Sulu Archipelago with speakers in the Zamboanga Peninsula and the Malaysian state of Sabah. Other Austronesian languages spoken by their respective tribes are the Sama-Bajau languages (although the Banguingui,the Samal and the Badjao share the same language, there ends the similarity; they are different in all other aspects especially when it comes to religion), as well as Yakan and Kalagan. Also spoken among the indigenous peoples of Mindanao and Sulu is Tagalog, for the sake of living in the Philippines and being a national language of the Philippines. There also exists a native Tagalog Muslim community in the Quiapo District of Metro Manila. Because of the mass influx of Cebuano migrants to Mindanao, many of the indigenous of Mindanao tend to be exposed to the Cebuano language from Visayan easily enough to be able to speak it, especially with the Tausūg since the language belongs to the Visayan family.

A sizeable minority speaks Malay, also an Austronesian language which was once the lingua franca of maritime Southeast Asia prior to contact with the European colonial powers. Today, many Moro merchants use Malay to converse with citizens of the neighbouring Malay-speaking nations of Malaysia, Indonesia and Brunei. Most of the Malay-speaking Muslims of the Philippines are those in the southern parts of the Zamboanga Peninsula, the Sulu Archipelago and the southern predominantly Muslim-inhabited municipalities of Bataraza and Balabac in Palawan. They likely speak a form of Malay creole. Many of the Tausūg in Malaysia and Indonesia (known there as Suluks) tend to lose their proficiency in both Tausūg and Chavacano, as well on Tagalog, as they became assimilated into the Malay-speaking majority of Malaysia, Indonesia and Brunei.

Chavacano (sometimes spelled as Chabacano or Chabakano) refer to a number of Philippine Spanish-based creole varieties found in the Philippines. The Zamboangueño variety, originating in Zamboanga city, is the variety with the most speakers. A number of the indigenous Muslim people have also attained the ability to speak this language, especially those that live in Zamboanga and Basilan. Aside from Christians (mostly Roman Catholics), Chavacano is also spoken by Muslims in Mindanao and Sulu as a second language. Chavacano also contains communities of speakers in Semporna, Sabah.[17]

Arabic is also spoken by a minority of the Moro people, being the liturgical language of Islam. Most Muslim indigenous people however, do not know Arabic beyond its religious uses. Most of the languages of the indigenous people are written in the Latin script. However, an Arabic script known as Jawi is used to write Tausūg language. Attempts are being made to make Jawi an official script in the future Bangsamoro entity.

Education

Generally, the indigenous people populace are educated. Some of the indigenous people who are Muslims choose Islamic Education and enrolled in Islamic/Arabic Institutions such as Jamiatul Mindanao Al-Islamie located in Marawi City. With the assistance of scholarship grants, some even attend university outside the country. The most popular schools for Moro outside the country are Al-Azhar University in Cairo, Egypt and Islamic University of Madinah, Saudi Arabia. However, the majority complete English/Western Education. Many attend Mindanao State University, the second biggest state university in the Philippines next to University of the Philippines, which has several campuses across Mindanao and has its Main Campus located at the heart of Islamic City of Marawi. Mindanao State University also has an Islamic Institute within its campus (the King Faisal Centre for Islamic Arabic, Asian Studies). Some indigenous people students are enrolled at other institutions both private and government especially in key cities such as Davao, Cebu and Manila.

History

Early history

In the 13th century, the arrival of Muslim missionaries from the Persian Gulf,[18] in particular Makhdum Karim, in Tawi-Tawi initiated the conversion of the native population into Islam. Trade between other sultanates in Brunei, Malaysia and Indonesia helped establish and entrench the Islamic religion in the southern Philippines. In 1457, the introduction of Islam led to the creation of Sultanates. This included the sultanates of Buayan, Maguindanao and the Sultanate of Sulu, which is considered the oldest Muslim government in the region until its annexation by the United States in 1898.

Like Brunei, Sulu and other Muslim sultanates in the Philippines were introduced to Islam through Chinese Muslims, Persians, and Arabs traders. Chinese Muslim merchants participated in the local commerce, and the Sultanate had diplomatic relations with Ming Dynasty China. As it was involved in the tribute system, the Sulu leader Paduka Batara and his sons moved to China, where he died and Chinese Muslims subsequently brought up his sons.[19] The inhabitants of pre-Hispanic Philippines practised Islam and Animism. The Malay kingdoms interacted, and traded with various tribes throughout the islands, governing several territories ruled by leaders called Rajah, Datu and Sultan. Before the arrival of Islam the Rajahs and Datus governed the territories.

Colonial period

Spanish conquest

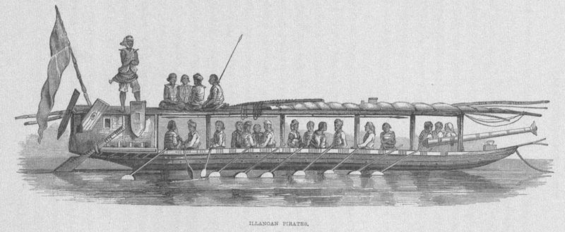

The Spaniards arrived in 1521 and the Philippines became part of the Spanish Empire in 1565. The Sultanates, however, actively resisted the Spaniards, thus maintaining their independence, enabling them to develop an Islamic culture and identity, different from the rest of the Catholic converted natives which the Spaniards called "Indios" (Indians). With intentions of colonising the islands, the Spaniards made incursions into Moro territory. They also began erecting military stations and garrisons with Catholic missions, which attracted Christianised natives of civilian settlements. The most notable of these are Zamboanga and Cotabato. Spain was in the midst of the Inquisition which required Jews and Muslims to convert to Roman Catholicism or leave or face the death penalty; thus Spaniards tried to ban and suppress Islam in areas they conquered. Feeling threatened by these actions, the Moros decided to challenge the Spanish government. They began conducting raids on Catholic coastal towns. These Moro raids reached a fevered pitched during the reign of Datu Bantilan in 1754.

The Spanish–Moro Conflict started at the phase of Castille War (Spanish-Bruneian War) of 1578, which created the war between Spaniards and Moros in areas held by Sultanate of Brunei, lasted several hundred years, while the Castille War itself lasted only two months. The string of coastal fortifications, military garrisons and forts built by the Spaniards ensured that these raids, although destructive to the Philippine economies of the coastal settlements, were eventually stifled. The advent of steam-powered naval ships in the 1800's finally drove the antiquated Moro navy of colourful proas and vintas to their bases. It took at least two decades of the presence of the Spanish in the Philippines for them to launch an extensive conquest of Mindanao.[20] The Sultanate of Sulu, one of the last Sultanates existing, itself soon fell under a concerted naval and ground attack from Spanish forces. In the last quarter of the 19th century Moros in the Sultanate of Sulu allowed the Spanish to build forts, but these areas remained loosely controlled by the Spanish as their sovereignty was limited to military stations and garrisons and pockets of civilian resettlements in Zamboanga and Cotabato (the latter under the Sultanate of Maguindanao), until the Spanish had to abandon the region as a consequence of their defeat in the Spanish–American War. Before that, in order to retain independence, the Sultanate of Sulu had given up its rule over Palawan to Spain in 1705 and Basilan to Spain in 1762; the areas that the Sulu Sultanate gave partial rule to Spain are Sulu and Tawi-Tawi.

%2C_Mindanao_Island.jpg)

In 1876, the Spaniards launched a campaign to colonise Jolo and made a final bid to establish a government in the southern islands. On 21 February of that year, the Spaniards assembled the largest contingent in Jolo, consisting of 9,000 soldiers in 11 transports, 11 gunboats and 11 steamboats. José Malcampo occupied Jolo and established a Spanish settlement with Pascual Cervera appointed to set up a garrison and serve as military governor. He served from March 1876 to December 1876 and was followed by José Paulin (December 1876-April 1877), Carlos Martínez (September 1877-February 1880), Rafael de Rivera (1880–1881), Isidro G. Soto (1881–1882), Eduardo Bremon, (1882), Julian Parrrado (1882–1884), Francisco Castilla (1884–1886), Juan Arolas (1886-1893), Caésar Mattos (1893), Venancio Hernández (1893–1896) and Luis Huerta (1896–1899).

_01.jpg)

The Chinese sold small arms like Enfield and Spencer Rifles to the Buayan Sultanate of Datu Uto. They were used to battle the Spanish invasion of the Sultanate of Buayan. The Datu paid for the weapons in slaves.[22]

The population of Chinese in Mindanao in the 1880s was 1,000. The Chinese ran guns across a Spanish blockade to sell to Mindanao Moros. The purchases of these weapons were paid for by the Moros in slaves in addition to other goods. The main group of people selling guns were the Chinese in Sulu. The Chinese took control of the economy and used steamers to ship goods for exporting and importing. Opium, ivory, textiles, and crockery were among the other goods which the Chinese sold. The Chinese on Maimbung sent the weapons to the Sulu Sultanate, who used them to battle the Spanish and resist their attacks. A Chinese-Mestizo was one of the Sultan's brothers-in-law, the Sultan was married to his sister. He and the Sultan both owned shares in the ship (named the Far East) which helped smuggle weapons.[22]

The Spanish launched a surprise offensive under Colonel Juan Arolas in April 1887 by attacking the Sultanate's capital at Maimbung in an effort to crush resistance. Weapons were captured and the property of the Chinese were destroyed while the Chinese were deported to Jolo.[22] By 1878, the Spanish had fortified Jolo with a perimeter wall and tower gates, built inner forts called Puerta Blockaus, Puerta España and Puerta Alfonso XII, and two outer fortifications named Princesa de Asturias and Torre de la Reina. Troops, including a cavalry with its own lieutenant commander, were garrisoned within the protective confine of the walls. In 1880, Rafael Gonzales de Rivera, who was appointed the governor, dispatched the 6th Regiment to govern Siasi and Bongao islands.

American colonisation

The United States claimed the territories of the Philippines, including long sovereign Sultanate Mindanao and Sulu, after the Spanish–American War. Since the loss of Spain to the United States, all the colony of Spain within the Philippine archipelago was ceded to the American in the Treaty of Paris which signalled the end of wars between the two. The Moros, who had successfully resisted Spanish colonisation, rejected the handover of their lands to the Americans and continued their struggle. This is the so-called Bangsamoro Question which has claimed over a million lives and trillions worth of properties and material. The Moro communities sovereign based conflict affects the Archipelago even today.

Japanese occupation

The Moros fought against the Japanese occupation of Mindanao and Sulu during World War II and eventually drove them out. Also when the Japanese occupied the northern Borneo area, they also helped their relatives there in a struggle to fight off the Japanese where many of them, including women and children, were massacred after their revolt with the Chinese had been foiled by the Japanese.

Modern days

In the modern day Philippines

Philippine government policies

After gaining independence from the United States, the Moro population, which was isolated from the mainstream and experienced discrimination by the Philippine government, added to the fact that they were now governed by what they view as the former foot soldiers of Spain, their ancestral lands given away to settlers and corporations by land-tenure Laws, arming the settlers as militia in Mindanao, Filipinisation was a government policy which eventually gave rise to armed secession movements.[3][23] Thus, the struggle for independence has been in existence for several centuries, starting from the Spanish period, the Moro rebellion during the United States occupation and up to the present day. Modern day Moro conflict began in the 1960s. During the period, the Philippine government envisioned a new country in which Christian and Moro would be assimilated into the dominant culture. This vision, however, was generally rejected by both groups, the Christians rembering stories from Spanish foot soldiers of how fierce the Moro was, and the Moro remembering the Christian as aiding its hated Spanish enemy for 300 years. These two prejudices continue to this day. Because of this, the National government realised that there was a need for a specialised agency to deal with the Moro community, so it set up the Commission for National Integration (CNI) in the 1960s, which was later replaced by the Office of Muslim Affairs, and Cultural Communities (OMACC) and later on as OMA.

As they thought, concessions were made to the Moro after the creation of these agencies, with the Moro population receiving exemptions from national laws prohibiting polygamy and divorce which the Moro has already been exercising. In 1977, the Philippine government made another palliative attempt to move a step further by harmonising Moro customary law with the national law which has no bearing at all for the Moro. Naturally, most of these achievements were seen as superficial. The Moro, still dissatisfied with the past Philippine governments' policies and misunderstanding established a first separatist group known as the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) led by Nur Misuari with the intention of creating an independent country. This initiated the modern Moro conflict in the Philippines, which still persists, and has since deepened the fractures between Muslims, Christians, and people of other religions. The MNLF is the only recognised representative organisation for the Muslims of the Philippines by the Organisation of the Islamic Cooperation (OIC). By the 1970s, a paramilitary organisation created by settler mayors in collusion with the Philippine Constabulary, mainly of armed Hiligaynon-speaking Christian residents of mainland Mindanao, called the Ilagas began operating in Cotabato originating from settler communities.[24] In response, Moro volunteers with minimal weapons also group themselves with much old traditional weapons like the kris, spears and barong, such as the Blackshirts of Cotabato and the Barracudas of Lanao, began to appear and engage the Ilagas. The Armed Forces of the Philippines were also deployed; however, their presence only seemed to create more violence and reports that the Army and the settler militia are helping each other.[25] A Zamboangan version of the Ilagas, the Mundo Oscuro (Spanish for Dark World), was also organised in Zamboanga and Basilan.

In 1981, internal divisions within the MNLF caused the establishment of an Islamic paramilitary breakaway organisation called the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). The group continued the conflict when the MNLF signed a Peace Deal with the Philippine Government in 1994. It has now become the biggest and most organised Moro armed group in Mindanao and Sulu. The Moro Islamic Liberation Front is now on the final stages of the required annexe for the Framework Agreement on the Bangsamoro that has a set time-frame for full implementation in 2016.

Autonomy

Although initialled in a 1976 ceasefire, come 1987 as a fall out of the EDSA revolution, peace talks with the MNLF picked up pace with the intention of establishing an autonomous region for Muslims in Mindanao. On 1 August 1989, through Republic Act No. 6734, known as the Organic Act, a 1989 plebiscite was held in 18 provinces in Mindanao, the Sulu Archipelago and Palawan without considering the effects of continuous migration by settlers from Luzón and the Visayas. This was said to determine if the residents would still want to be part of an Autonomous Region. Out of all the Provinces and cities participating in the plebiscite, only four provinces opted to join, namely: Maguindanao, Lanao del Sur, Sulu and Tawi-Tawi. Even its regional capital, Cotabato City, rejected joining the autonomous region as the settlers has now greatly outnumbered the Moro and Lumad. When before they were a majority, they have now become a minority. This still led to the creation of the ARMM, however. A second plebiscite, held a year more in 2001, managed to include Basilan (except its capital, Isabela City) and Marawi City in the autonomous region. Of the original 13 provinces agreed on the Final Peace Agreement (FPA) with the MNLF, only 5 has now been included in the present day ARMM due to the continuous settler program of the Republic of the Philippines that started in the earnest of 1901.

The ARMM is headed by a regional governor as the outcome of the Final Peace Agreement between the MNLF and the Philippine government in 1996 under President Fidel Ramos. The regional governor, with the regional-vice governor, act as the executive branch and are served by a Regional Cabinet, composed of regional secretaries, mirroring national government agencies of the Philippines. The ARMM has a unicameral Regional Assembly headed by a speaker. This acts as the legislative branch for the region and is responsible for regional ordinances. It is composed of three members for every congressional district. The current membership is twenty-four. Some of the Regional Assembly's acts have since been nullified by the Supreme Court on grounds that they are "unconstitutional". An example is the nullification of the creation of the Province of Shariff Kabungsuwan by the Regional Legislative Assembly (RLA) as this will create an extra seat in the Philippines Congress' House of Representatives, a power reserved solely for the Philippine Congress — Senate and House jointly — to decide on. Some would say, that this proves in itself the fallacy of its Autonomy granted by the Central Government during the Peace Process.

Current situation

The Moros had a history of resistance against Spanish, American, and Japanese rule for over 400 years. The armed struggle against the Spanish, Americans, Japanese and Filipinos is considered by present Moro leaders as part of the four centuries long "sovereign based conflict" of the Bangsamoro (Moro Nation).[26] The 400-year-long resistance against the Japanese, Americans, and Spanish by the Moro persisted and morphed into their current war for independence against the Philippine state.[27] Some Moros have formed their own separatist organisations such as the MNLF, MILF and become a members of more extreme groups such as the Abu Sayyaf (ASG) and Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) and the latest formed is Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighter ( BIFF). Now, even the armed Communist Party has gained its foothold in Mindanao with large Lumad adherents.

The Moro Islamic Liberation Front boycotted the original referendum formed by the Organic Act referendum and continued their armed struggle until present. However, it remains a partner to the peace process, with the Philippines unwilling to brand MILF as a "terrorist" group.[28] Today, the Moro people had become marginalises and a minority in Mindanao, they are also disadvantaged than majority Christians in terms of employment and housing; they are also discriminated.[29] Due to this, it has established escalating tensions that have contributed to the ongoing conflict between the Philippine government and the Moro people. In addition, there has been a large exodus of Moro peoples comprising the Tausūg, Samal, Bajau, Illanun and Maguindanao to Malaysia (Sabah) and Indonesia (North Kalimantan) since the 1970s, due to the illegal annexation of their land by the Catholic majority, and armed Settler militias such as the Ilaga which has destroyed the trust between Mindanao Settlers and Moro communities. Further, Land Tenure Laws has changed the population statistics of the Bangsamoro to a significant degree, and has caused the gradual displacement of the Moros from their traditional lands.[30]

2014 Draft Bangsamoro Basic Law

The office of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process has posted a set of frequently asked questions about the Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL), the draft of which President Benigno Aquino III submitted to Congress leaders. The Bangsamoro Basic Law abolishes the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao and establishes the new Bangsamoro political identity in its place. The law is based on the Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro signed by the Philippine government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front in March 2014. It is still to be Implemented by the Government by Congressional mandate.

In Malaysia

Due to their conflict in the southern Philippines, many Moros have emigrated to the Malaysian state of Sabah since the 1970s in search of better lives because of the close proximity between Sulu islands and the state of Sabah.[31] Most of them are illegal immigrants and live in squalor, thus he Sabah state government are working to relocate them into a proper settlement to ease management.[32]

Bangsa Sug and Bangsa Moro

In 2018, a unification gathering of all the sultans of the Sulu archipelago and representatives from all ethnic communities in the Sulu archipelago commenced in Zamboanga City, declaring themselves as the Bangsa Sug peoples and separating them from the Bangsa Moro peoples of mainland central Mindanao. They cited the complete difference in cultures and customary ways of life they have with the central Mindanao Muslims as the primary reason for their separation. They also called the government to establish a separate Philippine state, called Bangsa Sug, from mainland Bangsa Moro or to incorporate the Sulu archipelago to whatever state is formed in the Zamboanga peninsula, if ever federalism in the Philippines is approved in the coming years.[33]

See also

References

- 1 2 Philippines. 2013 Report on International Religious Freedom (Report). United States Department of State. July 28, 2014. SECTION I. RELIGIOUS DEMOGRAPHY.

The 2000 survey states that Islam is the largest minority religion, constituting approximately 5 percent of the population. A 2012 estimate by the National Commission on Muslim Filipinos (NCMF), however, states that there are 10.7 million Muslims, which is approximately 11 percent of the total population.

- ↑ https://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2004/35425.htm. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 James R. Arnold (26 July 2011). The Moro War: How America Battled a Muslim Insurgency in the Philippine Jungle, 1902-1913. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-1-60819-365-3.

- ↑ "Philippines: Insecurity and insufficient assistance hampers return". Norwegian Refugee Council. ReliefWeb. 13 August 2003. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ↑ https://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2004/35425.htm. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Deal sealed but to most Filipinos, Malaysia is home". The Star. 9 October 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 Jamail A. Kamlian (20 October 2012). "Who are the Moro people?". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ↑ "Press briefing by Presidential Spokesperson Lacierda and GPH Peace Panel Chairman Leonen". Official Gazette. Government of the Philippines. 8 October 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ↑ William Larousse (1 January 2001). A Local Church Living for Dialogue: Muslim-Christian Relations in Mindanao-Sulu, Philippines : 1965-2000. Gregorian Biblical BookShop. ISBN 978-88-7652-879-8.

- 1 2 "Framework Agreement on the Bangsamoro". Office of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process. Scribd. 7 October 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ↑ "BANGSAMORO CONSTITUTION: ROAD MAP TO INDEPENDENCE AND NATIONAL SELF-DETERMINATION". Moro National Liberation Front. 23 August 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ↑ William B. Depasupil (17 February 2014). "Military says Misuari 'hiding like a rat'". The Manila Times. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ↑ Senator Aquilino "Koko" Pimentel III (27 November 2013). "Resolution directing the appropriate Senate Committee's, to conduct an inquiry, in aid of legislation, on the motives, behind the Zamboanga City siege in September 2013 which resulted in a humanitarian crisis in the said city, with the end in view of enacting measures to prevent the reccurrence of a similar incident in the future" (PDF). Philippine Senate. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- 1 2 Vaudine England (8 September 2008). "Is Philippine peace process dead?". BBC News. Retrieved 9 September 2008.

- ↑ Nick Joaquin, Culture and History: Occasional Notes on the Process of Philippine Becoming (Pasig: Anvil Publishing, 2004), 226.

- ↑ "YouTube". Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ↑ Susanne Michaelis (2008). Roots of Creole Structures: Weighing the Contribution of Substrates and Superstrates. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 90-272-5255-6.

- ↑ M.R. Izady. "The Gulf's Ethnic Diversity: An Evolutionary History. in G. Sick and L. Potter, eds., Security in the Persian Gulf Origins, Obstacles, and the Search for Consensus,(NYC: Palgrave, 2002)

- ↑ P. N. Abinales; Donna J. Amoroso (1 January 2005). State and Society in the Philippines. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 43–. ISBN 978-0-7425-1024-1.

- ↑ Josephus Nelson Larned (1924). The New Larned History for Ready Reference, Reading and Research: The Actual Words of the World's Best Historians, Biographers and Specialists; a Complete System of History for All Uses, Extending to All Countries and Subjects and Representing the Better and Newer Literature of History. C.A. Nichols Publishing Company.

- ↑ Herbert W. Krieger (1899). The Collection of Primitive Weapons and Armor of the Philippine Islands in the United States National Museum. Smithsonian Institution - United States National Museum - Bulletin 137. Washington: Government Printing Office.

- 1 2 3 James Francis Warren (2007). The Sulu Zone, 1768-1898: The Dynamics of External Trade, Slavery, and Ethnicity in the Transformation of a Southeast Asian Maritime State. NUS Press. pp. 129–. ISBN 978-9971-69-386-2.

- ↑ Nelly van Doorn-Harder. "Southeast Asia, Islam in." Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World. Edited by Martin, Richard C. Macmillan Reference, 2004. vol. 1 p. 647.

- ↑ John Unson (28 September 2013). "Anti-Moro group resurfaces in NCotabato". The Philippine Star. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ↑ "Documentation for Ilagas". University of Mannheim. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ↑ Rommel C. Banlaoi. "Al Harakatul Al Islamiyyah: Essays on the Abu Sayyaf Group". Academia.edu. p. 24/137. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ↑ Rommel C. Banlaoi (2005). "Maritime Terrorism in Southeast Asia (The Abu Sayyaf Threat)". Newport, Rhode Island: Naval War College. p. 68/7. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ↑ http://www.opendemocracy.net/madrid11/philippines_130707 Archived 11 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Simon Montlake (19 January 2005). "Christians in Manila decry mall's Muslim prayer room". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ↑ Howe, Brendan M. (April 8, 2016). Post-Conflict Development in East Asia. Routledge. ISBN 1317077407. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ↑ Mencari Indonesia: demografi-politik pasca-Soeharto (in Indonesian). Yayasan Obor Indonesia. 2007. pp. 123–. ISBN 978-979-799-083-1.

- ↑ Muguntan Vanar (16 February 2016). "Sabah aims to end squatter problem". The Star. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ↑ http://www.sunstar.com.ph/article/1742513/Zamboanga/Local-News/Sulu-Sultanate-Bangsa-Sug-push-revision-of-Bangsamoro-Basic-Law

Further reading

- Federico V. Magdalena, "Moro-American Relations in the Philippines." Philippine Studies 44.3 (1996): 427-438. online

- The Moro struggle as myth and as historical reality (archive link) by Patricio N. Abinales of the Rappler

- The Bangsamoro Struggle for Self-Determination by Guiamel M. Alim of the Centre for Southeast Asian Studies

- The "Moro Problem" in the Philippines: Three Perspectives City University of Hong Kong (CityU)

- The Moro Conflict and the Philippine Experience with Autonomy Australian National University (ANU)

- Salah Jubair (1999). Bangsamoro, a Nation Under Endless Tyranny. IQ Marin.

- Bobby M. Tuazon (2008). The Moro reader: history and contemporary struggles of the Bangsamoro people. Policy Study Publication and Advocacy, Center for People Empowerment in Governance in partnership with Light a Candle Movement for Social Change. ISBN 978-971-93651-6-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Moro people. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Moro people |

Moro nationalists/separatists:

Moro websites:

- Bangsamoro.com Bangsamoro Online

- Moro Herald Bangsamoro News, History, Tradition, Politics, and Social Commentary

- Moro Bloggers