Matzo

Machine-made matzot from Jerusalem | |

| Alternative names | Matzo, matza |

|---|---|

| Type | Flatbread |

Matzo, matzah, or matza (Yiddish: מצה matsah, Hebrew: מַצָּה matsa; plural matzot; matzos of Ashkenazi Jewish dialect) is an unleavened flatbread that is part of Jewish cuisine and forms an integral element of the Passover festival, during which chametz (leaven and five grains that, per Jewish Law, can be leavened) is forbidden.

As the Torah recounts, God commanded the Jews[1] to create this special unleavened bread. During Passover it is eaten as a flat, cracker-like bread or used in dishes as breadcrumbs and in the traditional matzo ball soup.

Matzo that is kosher for Passover is limited in Ashkenazi tradition to plain matzo made from flour and water. The flour may be whole grain or refined grain, but must be either wheat, spelt, barley, rye, or oat. Some Sephardic communities allow matzos containing eggs and fruit juice to be used throughout the holiday.[2]

Passover and non-Passover matzo may be soft or crisp, but only the crisp "cracker" type is available commercially in most locations. Soft matzo, if it were commercially available, would essentially be a kosher flour tortilla.

Non-Passover matzo may be made with onion, garlic, poppy seed, etc. It can even be made from rice, maize, buckwheat and other non-traditional flours that can never be used for Passover matzo. Gluten-free matzo-lookalike made from potato starch, tapioca, and other non-traditional flour is available and may be eaten on Passover, but does not fulfill the commandment of eating matzo, even for people with celiac disease who cannot eat Passover matzo, because matzo must be made from one of the five grains (wheat, barley, oat, spelt, and rye), all of which contain gluten, except for most (but not all) types of oat matzo.[3] Oat matzo may only be used by those who cannot have any other kind because it's not certain that oat is actually one of the five grains (it may be a mistranslation[4]), so those who can have wheat matzo should do so.

Biblical sources

Matzo is mentioned in the Torah several times in relation to The Exodus from Egypt:

That night, they are to eat the meat, roasted in the fire; they are to eat it with matzo and maror.

— Exodus 12:8

From the evening of the fourteenth day of the first month until the evening of the twenty-first day, you are to eat matzo.

— Exodus 12:18

You are not to eat any chametz with it; for seven days you are to eat with it matzo, the bread of affliction; for you came out of the land of Egypt in haste. Thus you will remember the day you left the land of Egypt as long as you live.

— Deuteronomy 16:3

For six days you are to eat matzo; on the seventh day there is to be a festive assembly for Ha Shem your God; do not do any kind of work.

— Deuteronomy 16:8

Religious significance

There are numerous explanations behind the symbolism of matzo. One is historical: Passover is a commemoration of the exodus from Egypt. The biblical narrative relates that the Israelites left Egypt in such haste they could not wait for their bread dough to rise; the bread, when baked, was matzo. (Exodus 12:39). The other reason for eating matzo is symbolic: On the one hand, matzo symbolizes redemption and freedom, but it is also lechem oni, "poor man's bread". Thus it serves as a reminder to be humble, and to not forget what life was like in servitude. Also, leaven symbolizes corruption and pride as leaven "puffs up". Eating the "bread of affliction" is both a lesson in humility and an act that enhances the appreciation of freedom.

Another explanation is that matzo has been used to replace the pesach, or the traditional Passover offering that was made before the destruction of the Temple. During the Seder the third time the matzo is eaten it is preceded with the Sephardic rite, "zekher l'korban pesach hane'ekhal al hasova". This means "remembrance of the Passover offering, eaten while full". This last piece of the matzo eaten is called afikoman and many explain it as a symbol of salvation in the future.

The Passover Seder meal is full of symbols of salvation, the closing line, "Next year in Jerusalem," but the use of matzo is the oldest symbol of salvation in the Seder.[5]

Ingredients

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 1,653 kJ (395 kcal) |

|

83.70 g | |

|

1.40 g | |

|

10.00 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A | 0 IU |

| Thiamine (B1) |

34% 0.387 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) |

24% 0.291 mg |

| Niacin (B3) |

26% 3.892 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) |

9% 0.443 mg |

| Vitamin B6 |

9% 0.115 mg |

| Folate (B9) |

4% 17.1 μg |

| Vitamin B12 |

0% 0.00 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium |

1% 13 mg |

| Iron |

24% 3.16 mg |

| Magnesium |

7% 25 mg |

| Manganese |

31% 0.650 mg |

| Phosphorus |

13% 89 mg |

| Potassium |

2% 112 mg |

| Sodium |

0% 0 mg |

| Zinc |

7% 0.68 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 4.30 g |

|

(Values are for matzo made with enriched flour) | |

| |

|

†Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

At the Passover seder, simple matzo made of flour and water is mandatory. Sephardic tradition additionally permits the inclusion of eggs in the recipe. The flour must be ground from one of the five grains specified in Jewish law for Passover matzo: wheat, barley, spelt, rye or oat. Per Ashkenazic tradition, matzo made with wine, fruit juice, onion, garlic, etc., is not acceptable for use at any time during the Passover festival except by the elderly or unwell.[6][2]

Preparation

Matzo dough is quickly mixed and rolled out without an autolyse step as used for leavened breads. Most forms are pricked with a fork or a similar tool to keep the finished product from puffing up, and the resulting flat piece of dough is cooked at high temperature until it develops dark spots, then set aside to cool and, if sufficiently thin, to harden to crispness. Dough is considered to begin the leavening process 18 minutes from the time it gets wet; sooner if eggs, fruit juice, or milk is added to the dough. The entire process of making matzo takes only a few minutes in efficient modern matzo bakeries.

After baking, matzo may be ground into fine crumbs, known as matzo meal. Matzo meal can be used like flour during the week of Passover when flour can otherwise be used only to make matzo.

Variations

There are two major forms of matzo. In many western countries the most common form is the hard form of matzo which is cracker-like in appearance and taste and is used in all Ashkenazic and most Sephardic communities. Yemenites, and Iraqi Jews traditionally made a form of soft matzo which looks like Greek pita or like a tortilla. Soft matzo is made only by hand, and generally with shmurah flour.[7]

Flavored varieties of matzo are produced commercially, such as poppy seed- or onion-flavored. Oat and spelt matzo with kosher certification are produced. Oat matzo is generally suitable for those who cannot eat gluten. Whole wheat, bran and organic matzo are also available.[8] Chocolate-covered matzo is a favorite among children, although some consider it "enriched matzo" and will not eat it during the Passover holiday. A quite different flat confection of chocolate and nuts that resembles matzo is sometimes called "chocolate matzo".

Matzo contains typically 111 calories per 1-ounce/28g (USDA Nutrient Database), about the same as rye crispbread.

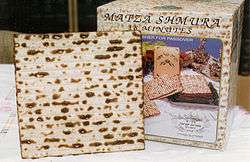

Shmurah matzo

Shĕmura ("guarded") matzo (Hebrew: מַצָּה שְׁמוּרָה matsa shĕmura) is made from grain that has been under special supervision from the time it was harvested to ensure that no fermentation has occurred, and that it is suitable for eating on the first night of Passover. (Shĕmura wheat may be formed into either handmade or machine-made matzo, while non-shĕmura wheat is only used for machine-made matzo. It is possible to hand-bake matzo in shĕmura style from non-shmurah flour—this is a matter of style, it is not actually in any way shĕmura—but such matzo has rarely been produced since the introduction of machine-made matzo.)

Haredi Judaism is scrupulous about the supervision of matzo and have the custom of baking their own or at least participating in some stage of the baking process. Rabbi Haim Halberstam of Sanz ruled that machine-made matzo were chametz.[9] According to that opinion, handmade non-shmurah matzo may be used on the eighth day of Passover outside of the Holy Land. However the non-Hasidic Haredi community of Jerusalem follows the custom that machine-made matzo may be used, with preference to the use of shĕmurah flour, in accordance with the ruling of Rabbi Yosef Haim Sonnenfeld, who ruled that machine-made matzo may be preferable to hand made in some cases. The commentators to the Shulhan `Aruch record that it is the custom of some of Diaspora Jewry to be scrupulous in giving Hallah from the dough used for baking "Matzot Mitzvah" (the Shĕmurah matzo eaten during Passover) to a Kohen child to eat.[10]

Egg matzo

"Egg (sometimes enriched) matzo" are matzot usually made with fruit juice, often grape or apple juice instead of water, but not necessarily with eggs themselves. There is a custom among some Ashkenazi Jews not to eat them during Passover, except for the elderly, infirm, or children, who cannot digest plain matzo; these matzot are considered to be kosher for Passover if prepared otherwise properly. The issue of whether egg matzo is allowed for Passover comes down to whether there is a difference between the various liquids that can be used. Water facilitates fermentation of grain flour, but the question is whether fruit juice, eggs, honey, oil or milk are also deemed to do so.

The Talmud, Pesachim 35a, states that liquid food extracts do not cause flour to leaven the way that water does. According to this view, flour mixed with other liquids would not need to be treated with the same care as flour mixed with water. The Tosafot (commentaries) explain that such liquids only produce a leavening reaction within flour if they themselves have had water added to them and otherwise the dough they produce is completely permissible for consumption during Passover, whether or not made according to the laws applying to matzot.

As a result, Joseph ben Ephraim Karo, author of the Shulchan Aruch or "Code of Jewish Law" (Orach Chayim 462:4) granted blanket permission for the use of any matzo made from non-water-based dough, including egg matzo, on Passover.[11] Many egg matzo boxes no longer include the message, "Ashkenazi custom is that egg matzo is only allowed for children, elderly and the infirm during Passover." Even amongst those who consider that enriched matzot may not be eaten during Passover, it is permissible to retain it in the home.

Cooking with matzo

Matzo may be used whole, broken, chopped ("matzo farfel"), or finely ground ("matzo meal") to make numerous matzo-based cooked dishes. These include matzo balls, which are traditionally served in chicken soup; matzo brei, a dish of Ashkenazi origin made from matzo soaked in water, mixed with beaten egg, and fried; matzo pizza, in which the piece of matzo takes the place of pizza crust and is topped with melted cheese and sauce;[12] and kosher for Passover cakes and cookies, which are made with matzo meal or a finer variety called "cake meal" that gives them a denser texture than ordinary baked foods made with flour. Hasidic Jews do not cook with matzo, believing that mixing it with water may allow leavening;[7] this stringency is known as gebrochts.[13] However, Jews who avoid eating gebrochts will eat cooked matzo dishes on the eighth day of Passover outside the Land of Israel, as the eighth day is of rabbinic and not Torah origin.[13]

Sephardim use matzo soaked in water or stock to make pies or lasagne,[14][15] known as mina, méguena, mayena or Italian: scacchi.[16]

In Christianity

Communion wafers used by the Catholic Church as well as in some Protestant traditions for the Eucharist are flat, unleavened bread. The main reason for the use of this bread is the belief, that because the last supper was described in the Synoptic Gospels as a passover meal, the unleavened matzo bread was used by Jesus when he held it up and said "this is my body". All Byzantine Rite churches use leavened bread for the Eucharist as this symbolizes the risen Christ.

Some Oriental Orthodox and Eastern Catholic Christians use leavened bread, as in the east there is the tradition, based upon the gospel of John, that leavened bread was on the table of the Last Supper. In the Armenian Apostolic Church, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church and Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church, unleavened bread called qǝddus qurban in Ge'ez, the liturgical language of the Eritreans and Ethiopians, is used for communion.

Catholic Christians living on the Malabar coast of Kerala, India have the customary celebration of Pesaha in their homes. On the evening before Good Friday, Pesaha bread is made at home. It is made with unleavened flour and they consume a sweet drink made up of coconut milk and jaggery along with this bread. On the Pesaha night, the bread is baked (steamed) immediately after rice flour is mixed with water and they pierce it many times with handle of the spoon to let out steam so that the bread will not rise (this custom is called "juthante kannu kuthal" in the Malayalam language meaning "piercing the bread according to the custom of Jews"). This bread is cut by the head of the family and shared among the family members.[17]

In Israel, the Saint James Vicariate For Hebrew Speaking Catholics uses matzo as the host for the Eucharistic celebration in the Mass as a form of inculturation.

World War II

At the end of World War II, the National Jewish Welfare Board had a matzo factory (according to the American Jewish Historical Society, it was probably the Manischewitz matzo factory in New Jersey) produce matzo in the form of a giant "V" for "Victory", for shipment to military bases overseas and in the U.S., for Passover seders for Jewish military personnel.[18] Passover in 1945 began on 1 April, when the collapse of the Axis in Europe was clearly imminent; Germany surrendered five weeks later.

See also

References

- ↑ Exodus 12:15

- 1 2 Posner, Menachem. "Is Egg Matzah Kosher For Passover?". Chabad.org. Lubavitch World Headquarters. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ↑ Butnick, Stephanie. "This Matzo Isn't a Mitzvah." Tablet Magazine.

- ↑ Linzer, Dov (20 May 2011). "Are Oats Really one of the 5 Species of Grain? – When Science and Halakha Collide". The Daily Daf. Archived from the original on 30 June 2011.

- ↑ Bradshaw, Paul F., and Hoffman, Lawrence A. Passover and Easter: The Symbolic Structuring of Sacred Seasons. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 1999.

- ↑ Mishna Brurah 462:1 1

- 1 2 "In Time for the Holiday: What is Matzah? How is it Baked?". IsraelNationalNews.com. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

According to Jewish Law, once matzo is baked, it cannot become hametz. However, some Ashkenazim, chiefly in Hassidic communities, do not eat [wetted matzo], for fear that part of the dough was not sufficiently baked and might become hametz when coming in contact with water.

- ↑ "On organic matzah". Swordsandploughshares.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- ↑ חיים בן אריה ליבוש האלברשטאם. "See SH"UT Divrei Hayyim Siman 23". Hebrewbooks.org. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- ↑ Ba'er Hetev to Yoreh De'ah ch. 322 (minor par. 7), Shabbatai HaKohen to above chapter

- ↑ Rabbi Shais Taub of Chabad-Lubavitch. "Is Egg Matzah okay for Passover use?". Askmoses.com. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- ↑ Deutsch, Jonathan; Saks, Rachel D. (2008). Jewish American Food Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 98. ISBN 0313343209.

- 1 2 "'Gebrokts': Wetted Matzah". Chabad.org. 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ↑ Goldstein, Joyce (1998). Cucina ebraica: flavors of the Italian Jewish kitchen. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0811819695.

- ↑ DrGaellon. "Scacchi (Passover Lasagna)". Food.com. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ↑ Romanow, Katherine. "Eating Jewish: Scacchi (Italian Matzo Pie)". JWA.org. Jewish Women's Archive. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ↑ "[Unknown title]". Journal of Indo Judaic Studies (13): 57–71. 2013.

- ↑ American Jewish Historical Society, March 22, 2007 retrieved Oct. 21, 2011 Archived August 11, 2007, at Archive.is

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Matzah. |