Oat

| Oat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Oat plants with inflorescences | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Subfamily: | Pooideae |

| Genus: | Avena |

| Species: | A. sativa |

| Binomial name | |

| Avena sativa L. (1753) | |

The oat (Avena sativa), sometimes called the common oat, is a species of cereal grain grown for its seed, which is known by the same name (usually in the plural, unlike other cereals and pseudocereals). While oats are suitable for human consumption as oatmeal and rolled oats, one of the most common uses is as livestock feed. Oats are a nutrient-rich food associated with lower blood cholesterol when consumed regularly.[1]

Avenins present in oats (proteins similar to gliadin from wheat) can trigger celiac disease in a small proportion of people.[2][3] Also, oat products are frequently contaminated by other gluten-containing grains, mainly wheat and barley.[3][4][5]

Origin

The wild ancestor of Avena sativa and the closely related minor crop, A. byzantina, is the hexaploid wild oat, A. sterilis. Genetic evidence shows the ancestral forms of A. sterilis grew in the Fertile Crescent of the Near East.[6] Oats are usually considered a secondary crop, i.e., derived from a weed of the primary cereal domesticates, then spreading westward into cooler, wetter areas favorable for oats, eventually leading to their domestication in regions of the Middle East and Europe.[6]

Cultivation

| Oats production - 2016 Tonnes | |

|---|---|

Oats are best grown in temperate regions. They have a lower summer heat requirement and greater tolerance of rain than other cereals, such as wheat, rye or barley, so are particularly important in areas with cool, wet summers, such as Northwest Europe and even Iceland. Oats are an annual plant, and can be planted either in autumn (for late summer harvest) or in the spring (for early autumn harvest).

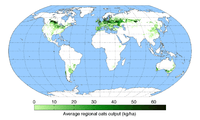

Production

In 2016, global production of oats was 23 million tonnes, led by Russia with 21% of the world total, followed by Canada with 13% of the total (table). Other substantial producers were Poland, Australia, and Finland, each with over one million tonnes.[7]

Uses

Oats have numerous uses in foods; most commonly, they are rolled or crushed into oatmeal, or ground into fine oat flour. Oatmeal is chiefly eaten as porridge, but may also be used in a variety of baked goods, such as oatcakes, oatmeal cookies and oat bread. Oats are also an ingredient in many cold cereals, in particular muesli and granola.

Historical attitudes towards oats have varied. Oat bread was first manufactured in Britain, where the first oat bread factory was established in 1899. In Scotland, they were, and still are, held in high esteem, as a mainstay of the national diet.

In Scotland, a dish was made by soaking the husks from oats for a week, so the fine, floury part of the meal remained as sediment to be strained off, boiled and eaten.[8] Oats are also widely used there as a thickener in soups, as barley or rice might be used in other countries.

Oats are also commonly used as feed for horses when extra carbohydrates and the subsequent boost in energy are required. The oat hull may be crushed ("rolled" or "crimped") for the horse to more easily digest the grain, or may be fed whole. They may be given alone or as part of a blended food pellet. Cattle are also fed oats, either whole or ground into a coarse flour using a roller mill, burr mill, or hammer mill. Oat forage is commonly used to feed all kinds of ruminants, as pasture, straw, hay or silage.[9]

Winter oats may be grown as an off-season groundcover and ploughed under in the spring as a green fertilizer, or harvested in early summer. They also can be used for pasture; they can be grazed a while, then allowed to head out for grain production, or grazed continuously until other pastures are ready.[10]

Oat straw is prized by cattle and horse producers as bedding, due to its soft, relatively dust-free, and absorbent nature. The straw can also be used for making corn dollies. Tied in a muslin bag, oat straw was used to soften bath water.

Oats are also occasionally used in several different drinks. In Britain, they are sometimes used for brewing beer. Oatmeal stout is one variety brewed using a percentage of oats for the wort. The more rarely used oat malt is produced by the Thomas Fawcett & Sons Maltings and was used in the Maclay Oat Malt Stout before Maclays Brewery ceased independent brewing operations. A cold, sweet drink called avena made of ground oats and milk is a popular refreshment throughout Latin America. Oatmeal caudle, made of ale and oatmeal with spices, was a traditional British drink and a favourite of Oliver Cromwell.[11][12]

Oat extracts can also be used to soothe skin conditions, and are popular for their emollient properties in cosmetics.[13]

Oat grass has been used traditionally for medicinal purposes, including to help balance the menstrual cycle, treat dysmenorrhoea and for osteoporosis and urinary tract infections.[14]

In China, particularly in western Inner Mongolia and Shanxi province, oat (Avena nuda) flour called youmian is processed into noodles or thin-walled rolls, and is consumed as staple food.

Health

Nutrient profile

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 1,628 kJ (389 kcal) |

|

66.3 g | |

| Dietary fiber | 11.6 g |

|

6.9 g | |

|

16.9 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Thiamine (B1) |

66% 0.763 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) |

12% 0.139 mg |

| Niacin (B3) |

6% 0.961 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) |

27% 1.349 mg |

| Vitamin B6 |

9% 0.12 mg |

| Folate (B9) |

14% 56 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium |

5% 54 mg |

| Iron |

38% 5 mg |

| Magnesium |

50% 177 mg |

| Manganese |

233% 4.9 mg |

| Phosphorus |

75% 523 mg |

| Potassium |

9% 429 mg |

| Sodium |

0% 2 mg |

| Zinc |

42% 4 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| β-glucan (soluble fibre) | 4 g |

|

| |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. | |

Oats are generally considered healthy due to their rich content of several essential nutrients (table). In a 100 gram serving, oats provide 389 calories and are an excellent source (20% or more of the Daily Value, DV) of protein (34% DV), dietary fiber (44% DV), several B vitamins and numerous dietary minerals, especially manganese (233% DV) (table). Oats are 66% carbohydrates, including 11% dietary fiber and 4% beta-glucans, 7% fat and 17% protein (table).

The established property of their cholesterol-lowering effects[1] has led to acceptance of oats as a health food.[15]

Soluble fiber

Oat bran is the outer casing of the oat. Its daily consumption over weeks lowers LDL and total cholesterol, possibly reducing the risk of heart disease.[1][16]

One type of soluble fiber, beta-glucans, has been proven to lower cholesterol.[1]

After reports of research finding that dietary oats can help lower cholesterol, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a final rule[17] that allows food companies to make health claims on food labels of foods that contain soluble fiber from whole oats (oat bran, oat flour and rolled oats), noting that 3.0 grams of soluble fiber daily from these foods may reduce the risk of heart disease. To qualify for the health claim, the food that contains the oats must provide at least 0.75 grams of soluble fiber per serving.[17]

Beta-D-glucans, usually referred to as beta-glucans, comprise a class of indigestible polysaccharides widely found in nature in sources such as grains, barley, yeast, bacteria, algae and mushrooms. In oats, barley and other cereal grains, they are located primarily in the endosperm cell wall. The oat beta-glucan health claim applies to oat bran, rolled oats, whole oat flour and oatrim, a soluble fraction of alpha-amylase hydrolyzed oat bran or whole oat flour.[17]

Oat beta-glucan is a viscous polysaccharide made up of units of the monosaccharide D-glucose. Oat beta-glucan is composed of mixed-linkage polysaccharides. This means the bonds between the D-glucose or D-glucopyranosyl units are either beta-1, 3 linkages or beta-1, 4 linkages. This type of beta-glucan is also referred to as a mixed-linkage (1→3), (1→4)-beta-D-glucan. The (1→3)-linkages break up the uniform structure of the beta-D-glucan molecule and make it soluble and flexible. In comparison, the indigestible polysaccharide cellulose is also a beta-glucan, but is not soluble because of its (1→4)-beta-D-linkages. The percentages of beta-glucan in the various whole oat products are: oat bran, having from 5.5% to 23.0%; rolled oats, about 4%; and whole oat flour about 4%.

Fat

Oats, after corn (maize), have the highest lipid content of any cereal, i.e. greater than 10% for oats and as high as 17% for some maize cultivars compared to about 2–3% for wheat and most other cereals. The polar lipid content of oats (about 8–17% glycolipid and 10–20% phospholipid or a total of about 33%) is greater than that of other cereals, since much of the lipid fraction is contained within the endosperm.

Protein

Oats are the only cereal containing a globulin or legume-like protein, avenalin, as the major (80%) storage protein.[18] Globulins are characterised by solubility in dilute saline as opposed to the more typical cereal proteins, such as gluten and zein, the prolamines (prolamins). The minor protein of oat is a prolamine, avenin.

Oat protein is nearly equivalent in quality to soy protein, which World Health Organization research has shown to be equal to meat, milk and egg protein.[19] The protein content of the hull-less oat kernel (groat) ranges from 12 to 24%, the highest among cereals.

Celiac disease

Celiac disease (coeliac disease) is a permanent intolerance to gluten proteins in genetically predisposed people, having a prevalence of about 1% in the developed world.[20] Gluten is present in wheat, barley, rye, oat, and all their species and hybrids[2][20] and contains hundreds of proteins, with high contents of prolamins.[21]

Oat prolamins, named avenins, are similar to gliadins found in wheat, hordeins in barley, and secalins in rye, which are collectively named gluten.[2] Avenins toxicity in celiac people depends on the oat cultivar consumed because of prolamin genes, protein amino acid sequences, and the immunoreactivities of toxic prolamins which vary among oat varieties.[3][4][22] Also, oats products are frequently cross-contaminated with other gluten-containing cereals during grain harvesting, transport, storage or processing.[4][22][23] Pure oats contain less than 20 parts per million of gluten from wheat, barley, rye, or any of their hybrids.[3][4]

Use of pure oats in a gluten-free diet offers improved nutritional value from the rich content of oat protein, vitamins, minerals, fiber, and lipids,[4][24] but remains controversial because a small proportion of people with celiac disease react to pure oats.[3][25] Some cultivars of pure oat could be a safe part of a gluten-free diet, requiring knowledge of the oat variety used in food products for a gluten-free diet.[3][4] Determining whether oat consumption is safe is critical because people with poorly controlled celiac disease may develop multiple severe health complications, including cancers.[26]

Use of pure oat products is an option, with the assessment of a health professional,[3] when the celiac person has been on a gluten-free diet for at least 6 months and all celiac symptoms have disappeared clinically.[3][27] Celiac disease may relapse in few cases with the consumption of pure oats.[28] Screening with serum antibodies for celiac disease is not sensitive enough to detect people who react to pure oats and the absence of digestive symptoms is not an accurate indicator of intestinal recovery because up to 50% of people with active celiac disease have no digestive symptoms.[28][29][30] The lifelong follow-up of celiac people who choose to consume oats may require periodic performance of intestinal biopsies.[26] The long-term effects of pure oats consumption are still unclear[26][27] and further well-designed studies identifying the cultivars used are needed before making final recommendations for a gluten-free diet.[23][24]

Agronomy

Oats are sown in the spring or early summer in colder areas, as soon as the soil can be worked. An early start is crucial to good fields, as oats go dormant in summer heat. In warmer areas, oats are sown in late summer or early fall. Oats are cold-tolerant and are unaffected by late frosts or snow.

Seeding rates

Typically, about 125 to 175 kg/ha (between 2.75 and 3.25 bushels per acre) are sown, either broadcast or drilled. Lower rates are used when interseeding with a legume. Somewhat higher rates can be used on the best soils, or where there are problems with weeds. Excessive sowing rates lead to problems with lodging, and may reduce yields.

Fertilizer requirements

Oats remove substantial amounts of nitrogen from the soil. They also remove phosphorus in the form of P2O5 at the rate of 0.25 pound per bushel (1 bushel = 38 pounds at 12% moisture). Phosphate is thus applied at a rate of 30 to 40 kg/ha, or 30 to 40 lb/acre. Oats remove potash (K2O) at a rate of 0.19 pound per bushel, which causes it to use 15–30 kg/ha, or 13–27 lb/acre. Usually, 50–100 kg/ha (45–90 lb/ac) of nitrogen in the form of urea or anhydrous ammonia is sufficient, as oats use about one pound per bushel. A sufficient amount of nitrogen is particularly important for plant height and hence, straw quality and yield. When the prior-year crop was a legume, or where ample manure is applied, nitrogen rates can be reduced somewhat.

Weed control

The vigorous growth of oats tends to choke out most weeds. A few tall broadleaf weeds, such as ragweed, goosegrass, wild mustard, and buttonweed (velvetleaf), occasionally create a problem, as they complicate harvest and reduce yields. These can be controlled with a modest application of a broadleaf herbicide, such as 2,4-D, while the weeds are still small.

Pests and diseases

Oats are relatively free from diseases and pests with the exception being leaf diseases, such as leaf rust and stem rust. However, Puccinia coronata var. avenae is a pathogen that can greatly reduce crop yields.[31] A few lepidopteran caterpillars feed on the plants—e.g. rustic shoulder-knot and setaceous Hebrew character moths, but these rarely become a major pest. See also List of oat diseases.

Harvesting

(Photo: Axel Lindahl/Norwegian Museum of Cultural History)

Harvest techniques are a matter of available equipment, local tradition, and priorities. Farmers seeking the highest yield from their crops time their harvest so the kernels have reached 35% moisture, or when the greenest kernels are just turning cream-colour. They then harvest by swathing, cutting the plants at about 10 cm (3.9 in) above ground, and putting the swathed plants into windrows with the grain all oriented the same way. They leave the windrows to dry in the sun for several days before combining them using a pickup header. Finally, they bale the straw.

Oats can also be left standing until completely ripe and then combined with a grain head. This causes greater field losses as the grain falls from the heads, and to harvesting losses, as the grain is threshed out by the reel. Without a draper head, there is also more damage to the straw, since it is not properly oriented as it enters the combine's throat. Overall yield loss is 10–15% compared to proper swathing.

Historical harvest methods involved cutting with a scythe or sickle, and threshing under the feet of cattle. Late 19th- and early 20th-century harvesting was performed using a binder. Oats were gathered into shocks, and then collected and run through a stationary threshing machine.

Storage

After combining, the oats are transported to the farmyard using a grain truck, semi, or road train, where they are augered or conveyed into a bin for storage. Sometimes, when there is not enough bin space, they are augered into portable grain rings, or piled on the ground. Oats can be safely stored at 12-14% moisture; at higher moisture levels, they must be aerated or dried.

Yield and quality

In the United States, No.1 oats weigh 42 pounds per US bushel (541 kg/m3); No.3 oats must weigh at least 38 lb/US bu (489 kg/m3). If over 36 lb/US bu (463 kg/m3), they are graded as No.4 and oats under 36 lb/US bu (463 kg/m3) are graded as "light weight".

In Canada, No.1 oats weigh 42.64 lb/US bu (549 kg/m3); No.2 oats must weigh 40.18 lb/US bu (517 kg/m3); No.3 oats must weigh at least 38.54 lb/US bu (496 kg/m3) and if oats are lighter than 36.08 lb/US bu (464 kg/m3) they do not make No.4 oats and have no grade.[32]

Note, however, that oats are bought and sold and yields are figured, on the basis of a bushel equal to 32 pounds (14.5 kg or 412 kg/m3) in the United States and a bushel equal to 34 pounds (15.4 kg or 438 kg/m3) in Canada. "Bright oats" were sold on the basis of a bushel equal to 48 pounds (21.8 kg or 618 kg/m3) in the United States.

Yields range from 60 to 80 US bushels per acre (5.2–7.0 m3/ha) on marginal land, to 100 to 150 US bushels per acre (8.7–13.1 m3/ha) on high-producing land. The average production is 100 bushels per acre, or 3.5 tonnes per hectare.

Straw yields are variable, ranging from one to three tonnes per hectare, mainly due to available nutrients and the variety used (some are short-strawed, meant specifically for straight combining).

Processing

Oats processing is a relatively simple process:

Cleaning and sizing

Upon delivery to the milling plant, chaff, rocks, other grains and other foreign material are removed from the oats.

Dehulling

Centrifugal acceleration is used to separate the outer hull from the inner oat groat. Oats are fed by gravity onto the centre of a horizontally spinning stone, which accelerates them towards the outer ring. Groats and hulls are separated on impact with this ring. The lighter oat hulls are then aspirated away, while the denser oat groats are taken to the next step of processing. Oat hulls can be used as feed, processed further into insoluble oat fibre, or used as a biomass fuel.

Kilning

The unsized oat groats pass through a heat and moisture treatment to balance moisture, but mainly to stabilize them. Oat groats are high in fat (lipids) and once removed from their protective hulls and exposed to air, enzymatic (lipase) activity begins to break down the fat into free fatty acids, ultimately causing an off-flavour or rancidity. Oats begin to show signs of enzymatic rancidity within four days of being dehulled if not stabilized. This process is primarily done in food-grade plants, not in feed-grade plants. Groats are not considered raw if they have gone through this process; the heat disrupts the germ and they cannot sprout.

Sizing of groats

Many whole oat groats break during the dehulling process, leaving the following types of groats to be sized and separated for further processing: whole oat groats, coarse steel cut groats, steel cut groats, and fine steel cut groats. Groats are sized and separated using screens, shakers and indent screens. After the whole oat groats are separated, the remaining broken groats get sized again into the three groups (coarse, regular, fine), and then stored. "Steel cut" refers to all sized or cut groats. When not enough broken groats are available to size for further processing, whole oat groats are sent to a cutting unit with steel blades that evenly cut groats into the three sizes above.

Final processing

Three methods are used to make the finished product:

Flaking

This process uses two large smooth or corrugated rolls spinning at the same speed in opposite directions at a controlled distance. After rolling, the oats are then toasted to make rolled oats. Oat flakes, also known as rolled oats, have many different sizes, thicknesses and other characteristics depending on the size of oat groats passed between the rolls. Typically, the three sizes of steel cut oats are used to make instant, baby and quick rolled oats, whereas whole oat groats are used to make regular, medium and thick rolled oats. Oat flakes range in thickness from 0.36 mm to 1.00 mm.

Oat bran milling

This process takes the oat groats through several roll stands to flatten and separate the bran from the flour (endosperm). The two separate products (flour and bran) get sifted through a gyrating sifter screen to further separate them. The final products are oat bran and debranned oat flour.

Whole flour milling

This process takes oat groats straight to a grinding unit (stone or hammer mill) and then over sifter screens to separate the coarse flour and final whole oat flour. The coarser flour is sent back to the grinding unit until it is ground fine enough to be whole oat flour. This method is used often in India and other countries. In India whole grain oat flour (jai) is used to make Indian bread known as jarobra in Himachal Pradesh.

Preparation at home

Oat flour can be ground for small scale use by pulsing rolled oats or old-fashioned (not quick) oats in a food processor or spice mill.[33][34]

Naming

In Scottish English, oats may be referred to as corn.[35] (In the English language, the major staple grain of the local area is often referred to as "corn".[36] In the US, "corn" originates from "Indian corn" and refers to what others call "maize" or "sweetcorn".)[36]

Oats futures

Oats futures are traded on the Chicago Board of Trade and have delivery dates in March (H), May (K), July (N), September (U) and December (Z).[37]

See also

Oat products and derivatives

Major oat businesses

References

- 1 2 3 4 Whitehead A, Beck EJ, Tosh S, Wolever TM (2014). "Cholesterol-lowering effects of oat β-glucan: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Am J Clin Nutr. 100 (6): 1413–21. doi:10.3945/ajcn.114.086108. PMC 5394769. PMID 25411276.

- 1 2 3 Biesiekierski JR (2017). "What is gluten?". J Gastroenterol Hepatol (Review). 32 Suppl 1: 78–81. doi:10.1111/jgh.13703. PMID 28244676.

Similar proteins to the gliadin found in wheat exist as secalin in rye, hordein in barley, and avenins in oats and are collectively referred to as “gluten.” Derivatives of these grains such as triticale and malt and other ancient wheat varieties such as spelt and kamut also contain gluten. The gluten found in all of these grains has been identified as the component capable of triggering the immune-mediated disorder, coeliac disease.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 La Vieille, S; Pulido, O. M.; Abbott, M; Koerner, T. B.; Godefroy, S (2016). "Celiac Disease and Gluten-Free Oats: A Canadian Position Based on a Literature Review". Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2016: 1–10. doi:10.1155/2016/1870305. PMC 4904695. PMID 27446825.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Comino I, Moreno Mde L, Sousa C (Nov 7, 2015). "Role of oats in celiac disease". World J Gastroenterol. 21 (41): 11825–31. doi:10.3748/wjg.v21.i41.11825. PMC 4631980. PMID 26557006.

It is necessary to consider that oats include many varieties, containing various amino acid sequences and showing different immunoreactivities associated with toxic prolamins. As a result, several studies have shown that the immunogenicity of oats varies depending on the cultivar consumed. Thus, it is essential to thoroughly study the variety of oats used in a food ingredient before including it in a gluten-free diet.

- ↑ Fric P, Gabrovska D, Nevoral J (Feb 2011). "Celiac disease, gluten-free diet, and oats". Nutr Rev (Review). 69 (2): 107–15. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00368.x. PMID 21294744.

- 1 2 Zhou, X.; Jellen, E.N.; Murphy, J.P. (1999). "Progenitor germplasm of domesticated hexaploid oat". Crop Science. 39 (4): 1208–1214. doi:10.2135/cropsci1999.0011183x003900040042x.

- 1 2 "Oats production in 2016, Crops/World Regions/Production Quantity from pick lists". Food and Agriculture Organization, Statistics Division, FAOSTAT. 2017. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ↑ Gauldie, Enid (1981). The Scottish country miller, 1700–1900: a history of water-powered meal milling in Scotland. Edinburgh: J. Donald. ISBN 978-0-85976-067-6.

- ↑ Heuzé V., Tran G., Boudon A., Lebas F., 2016. Oat forage. Feedipedia, a programme by INRA, CIRAD, AFZ and FAO. https://www.feedipedia.org/node/500 Last updated on April 13, 2016, 16:26

- ↑ "Grazing of Oat Pastures". eXtension. 2008-02-11. Retrieved 2013-03-27.

- ↑ The Compleat Housewife, p. 169, Eliza Smith, 1739

- ↑ Food in Early Modern Europe, Ken Albala, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2003, ISBN 0-313-31962-6

- ↑ Heuzé V., Tran G., Nozière P., Renaudeau D., Lessire M., Lebas F., 2016. Oats. Feedipedia, a programme by INRA, CIRAD, AFZ and FAO. https://www.feedipedia.org/node/231 Last updated on April 15, 2016, 11:21

- ↑ Duke, James A (2002-06-27). James A. Duke, Handbook of medicinal herbs, CRC Press, 2002. ISBN 9781420040463.

- ↑ "Nutrition for everyone: carbohydrates". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services. 2014. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- ↑ "LDL Cholesterol and Oatmeal". WebMD. 2 February 2009.

- 1 2 3 "Title 21--Chapter 1, Subchapter B, Part 101 - Food labeling - Specific Requirements for Health Claims, Section 101.81: Health claims: Soluble fiber from certain foods and risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) (revision 2015)". US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. 1 April 2015. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ↑ "Seed Storage Proteins: Structures 'and Biosynthesis" (PDF). Plantcell.org. Retrieved 2013-03-27.

- ↑ Lasztity, Radomir (1999). The Chemistry of Cereal Proteins. Akademiai Kiado. ISBN 978-0-8493-2763-6.

- 1 2 Tovoli F, Masi C, Guidetti E, Negrini G, Paterini P, Bolondi L (Mar 16, 2015). "Clinical and diagnostic aspects of gluten related disorders". World J Clin Cases. 3 (3): 275–84. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v3.i3.275. PMC 4360499. PMID 25789300.

- ↑ Lamacchia C, Camarca A, Picascia S, Di Luccia A, Gianfrani C (Jan 29, 2014). "Cereal-based gluten-free food: how to reconcile nutritional and technological properties of wheat proteins with safety for celiac disease patients". Nutrients. 6 (2): 575–90. doi:10.3390/nu6020575. PMC 3942718. PMID 24481131.

- 1 2 Penagini F, Dilillo D, Meneghin F, Mameli C, Fabiano V, Zuccotti GV (Nov 18, 2013). "Gluten-free diet in children: an approach to a nutritionally adequate and balanced diet". Nutrients. 5 (11): 4553–65. doi:10.3390/nu5114553. PMC 3847748. PMID 24253052.

- 1 2 de Souza MC, Deschênes ME, Laurencelle S, Godet P, Roy CC, Djilali-Saiah I (2016). "Pure Oats as Part of the Canadian Gluten-Free Diet in Celiac Disease: The Need to Revisit the Issue". Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol (Review). 2016: 1–8. doi:10.1155/2016/1576360. PMC 4904650. PMID 27446824.

- 1 2 Pinto-Sánchez, M. I.; Causada-Calo, N; Bercik, P; Ford, A. C.; Murray, J. A.; Armstrong, D; Semrad, C; Kupfer, S. S.; Alaedini, A; Moayyedi, P; Leffler, D. A.; Verdú, E. F.; Green, P (2017). "Safety of Adding Oats to a Gluten-free Diet for Patients with Celiac Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Clinical and Observational Studies". Gastroenterology (Systematic Review and Meta-analysis). 153 (2): 395–409.e3. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.009. PMID 28431885.

- ↑ Ciacci C, Ciclitira P, Hadjivassiliou M, Kaukinen K, Ludvigsson JF, McGough N; et al. (2015). "The gluten-free diet and its current application in coeliac disease and dermatitis herpetiformis". United European Gastroenterol J (Review). 3 (2): 121–35. doi:10.1177/2050640614559263. PMC 4406897. PMID 25922672.

- 1 2 3 Haboubi NY, Taylor S, Jones S (Oct 2006). "Coeliac disease and oats: a systematic review". Postgrad Med J (Review). 82 (972): 672–8. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2006.045443. PMC 2653911. PMID 17068278.

- 1 2 Pulido OM, Gillespie Z, Zarkadas M, Dubois S, Vavasour E, Rashid M; et al. (2009). Introduction of oats in the diet of individuals with celiac disease: a systematic review. Adv Food Nutr Res (Systematic Review). Advances in Food and Nutrition Research. 57. pp. 235–85. doi:10.1016/S1043-4526(09)57006-4. ISBN 9780123744401. PMID 19595389.

- 1 2 Rashid M, Butzner D, Burrows V, Zarkadas M, Case S, Molloy M; et al. (2007). "Consumption of pure oats by individuals with celiac disease: a position statement by the Canadian Celiac Association". Can J Gastroenterol (Guideline). 21 (10): 649–51. PMC 2658132. PMID 17948135.

- ↑ Moreno ML, Rodríguez-Herrera A, Sousa C, Comino I (2017). "Biomarkers to Monitor Gluten-Free Diet Compliance in Celiac Patients". Nutrients (Review). 9 (1): 46. doi:10.3390/nu9010046. PMC 5295090. PMID 28067823.

- ↑ Newnham ED (2017). "Coeliac disease in the 21st century: paradigm shifts in the modern age". J Gastroenterol Hepatol (Review). 32 Suppl 1: 82–85. doi:10.1111/jgh.13704. PMID 28244672.

Intuitively, resolution of symptoms, normalization of histology, and normalization of coeliac antibodies should define response to treatment. But asymptomatic CD may occur in up to 50% of affected individuals,5 symptoms correlate poorly with mucosal pathology,6 and even with excellent dietary adherence, histology and coeliac antibodies can take several years to normalize.7

- ↑ "Oat crown rust". Cereal Disease Laboratory. United States Department of Agriculture| Agricultural Research Service. 18 April 2008. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ↑ "Oats – Chapter 7 – Official Grain Grading Guide – 5 / 7". Grainscanada.gc.ca. 2012-07-27. Retrieved 2013-03-27.

- ↑ The Sparkpeople cookbook: love your food, lose the weight, Galvin, M., Romnie, S., May House Inc, 2011, ISBN 978-1-4019-3132-2, page 98.

- ↑ ["http://www.wisegeek.com/what-is-oat-flour.htm "What is out flour?"] wiseGeek.com. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ↑ Partridge, Eric (1995). Janet Whitcut, ed. Usage and Abusage: A Guide to Good English (1st American ed.). New York: W.W. Norton, 1995. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-393-03761-6.

- 1 2 NA (2007). Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 522. ISBN 978-0-19-920687-2.

- ↑ List of Commodity Delivery Dates on Wikinvest

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Avena sativa. |