Luftnachrichten Abteilung 350

The Luftnachrichten Abteilung 350, abbreviated as OKL/LN Abt 350 and formerly called the (German: Oberkommando der Luftwaffe Luftnachrichten Abteilung 350), was the Signal Intelligence Agency of the German Air Force, the Luftwaffe, before and during World War II.[1] Before November 1944, the unit was named as the Chi-Stelle O. b. D.L (German: Chiffrierstelle, Oberbefehlshaber der Luftwaffe, lit. 'code centre, High Commander of the Air Force'), which was often abbreviated to Chi-Stelle/Obdl or more commonly Chi-Stelle. The founding of the former agencies of OKL/LN Abt 350 dates back to the year 1936, when Colonel (later General) (German: Generalnachrichten-Führer der Luftwaffe) Wolfgang Martini instigated the creation of the agency, that was later established on the orders of Hermann Göring, the German politician, military leader, and leading member of the Nazi Party.[2] Right from the beginning, the Luftwaffe High Command resolved itself to make itself entirely independent from the German Army in the field of cryptology.[3][4]

Background

The LN Abt 350 was one of a large number of regiments which were named in that series, but there were several related regiments, which dealt with intelligence-related matters, of one kind or another. These were as follows:

- LN Regiment 351. Commanded by Major Ristow. Its task was the mapping and interception of communications intelligence of Allied air forces in England and France. It conducted air to air interception, ground to air, and ground to ground including tracking of navigational aids. It had three departments I, I and II.[4]

- LN Regiment 352. Commanded by Major Ferdinand Feichtner. Its task was mapping and interception of communication intelligence of Allied air forces in the Mediterranean area.[4]

- LN Regiment 353. Commanded by Colonel Hans Eick. Its task was the Soviet Air Force.[4]

- LN Abteilung 355. Commanded by Major Camerlander. Its task was Allied air forces in northern areas, specifically the Soviet Air Force in Northern Norway. It covered ground to ground, and air to air according to reception conditions.[4] This unit was formerly W-Leit 5 based in Oslo.

- LN Abteilung 356. Commanded by Captain Trattner. Its task was route tracking of Allied air forces by radar interception and in collaboration with LN Regiment 357.[4]

- LN Abteilung 357. Commanded by Captain Rueckheim. Its task was Allied four-engined formations and route tracking by intercepted signals and in collaboration with LN Abt. 356.[4]

- LN Abteilung 358. This was for training of intercept personnel.[4]

- LN Abteilung 359. Commanded by Captain de Wilde. Its task was the radio jamming of Allied communications, but it also conducted deception operations.[4]

Origin

As early as 1935, civilian employees of the Luftwaffe had been sent to fixed intercept stations of the German Army for training. A Luftwaffe officer, a technician and a civilian inspector who has been associated with the German Army Intelligence Service during World War I were transferred to the Luftwaffe Chi-Stelle. The two people canvassed for assistants among their old circle of acquaintances, former soldiers who had served in World War I as intercept technicians or cryptanalysts. Their numbers were no means sufficient for the task at hand.[2] They consisted of people who at one time, either in civilian or military life, had received radio training or who were fluent in foreign languages. Among them were old soldiers, former seamen, professional travellers, adventurers and political refugees. In contrast to the Army, security measures taken in admitting people to the Agency were superficial, and a great number were found to be of questionable character. These trainees made training more difficult. Owing to their privileged position, they had a derogatory influence on the Luftwaffe Agency.[5]

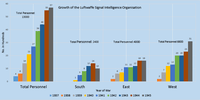

In creating the Chi-Stelle, the fundamental error was committed of choosing personnel indiscriminately, without any regard to their previous training for this special work. The civilian employees had training, but no training in Chi-Stelle type of work. The first technical equipment was very deficient. Old receivers from World War I were being used, and the installation alone was a technically difficult task, and therefore naturally unsuitable for the SIS. Even the later-installed multiple dial receivers were in part improvised.[6] Therefore, the importance of the Chi-Stelle in these first years remained slight, when it should have been assuming operation direction of the Luftwaffe Signal Intelligence Operation.[7] A small nucleus had been assembled, with independent Luftwaffe intercept experiments begun, and by the summer of 1936, traffic from Italy, Britain, Poland, Czechoslovakia and Russian air forces had been intercepted. The training of radio operations was supervised by a small cadre obtained from the Reichswehr cipher bureau. On 1 January, 1937, the agency was officially launched, under the Luftwaffe banner, with one officer and twenty civilians. It was called Chiffrier Stelle.[1] New Luftwaffe fixed intercept stations were founded in Munich, Münster, and Potsdam (Eiche) in 1937 and given the cover name of Weather Radio Receiving Stations (German: Wetterfunkempfangsstellen) (abbr. W-Stellen).[8] The Luftwaffe fixed intercept stations at first monitored only the air force point-to-point networks taken over by the Army. Since in peacetime, almost all countries sent their radio traffic in plaintext, the work was simple, and direction finding was unknown.[9] Personnel consisted at first of an officer in charge, two or three technicians and 30-40 civilian employees. Early training flights with the Zeppelin were carried out under the direction of the Chi-Stelle.[9]

Mobile intercept platoons were established at the same time, to operate in the field.[10][11] These small sections, about 10 analysts who undertook evaluation locally, corresponding to the monitoring areas of the three out-stations, were formed. The first dealt with England, France, and Belgium; the second with Italy, and the third with Russia, Poland and Czechoslovakia. To these were added a small cryptanalysis group, that was called the Chi-Stelle which served all three sections.[12] The intercept stations were supplemented by direction finding stations which were called Weather Research Stations (German: Wetterforschungsstellen) (abbr. Wo-Stellen), after the start of World War II. The small sections were expanded into mobile Radio Intercept Companies (German: Lufnachrichten Funkhorchkompanien Mot) which collaborated with the fixed stations in the intercept of foreign air force traffic.[13][11]

Relation to Luftwaffe Headquarters

The material sent from the out-stations to the Chi-Stelle Agency was classified according to tactical subject, and passed to the General Staff. Since, at this time, the Chi-Stelle itself was part of the General Staff, and as such was responsible for SIS planning and personnel policy, its importance in this early stage was considerable.[14] The intelligence passed to the General Staff was shared with the Chief of the Air Force, the Army, the Navy, and also the local air force: Luftlotte commanders. The Agency had the further duty of assigning intercept missions to the field units.[15][16] It soon became evident that the intelligence needs of the local air force (Luftflotte) commanders could be more quickly satisfied by having evaluation performed at a lower level than at the Agency. As a result, field evaluation centres of company strength were established and given the cover name of Weather Control Stations (German: Wetterleitstellen) (abbr. W-Leit).[17]

Plan for wartime organization

In 1939, after several experiments at reorganization, the fixed and mobile signal intelligence units were combined into Sig Int battalions, removed from the administrative control of Chi-Stelle, and attached to Local Air Force Signal Regiments, in each case as the third battalion of what was primarily a communication regiment. Each signal intelligence battalion was composed of an evaluation unit (the W-Leitstelle), two mobile intercept companies and three fixed intercept stations.[18][19] This decentralization of LNA 350 resulted the Chi-Stelle losing influence, especially at the outset of the war.[20]

In this organization, however, a serious mistake was made in that the above-mentioned companies were not activated immediately and taken under continuous training, as in the Army. Instead, they existed in the form of intercept platoons, which were trained by fixed intercept stations, the men being returned, after only a short period of training, to their radio companies in the Luftwaffe Signal Regiments. In this manner, a trained nucleus of personnel would have been built up before the war, as well as more than a few hundred civilian employees, which could be called upon at the start of the war. The functioning of the LNA 350 in the early months of the war was entirely to the credit of civilian employees, since it was they who had a knowledge of the activities.[21]

Start of War

With the start of the war, the Chi-Stelle was already an organization of some 1400 people. For a whole year prior to the war, the fixed Chi-Stelle stations had been systematically covering the air force traffic of foreign countries. Their work was complemented by revealing press reports and other sources of intelligence, the results being that the High Command, prior to the outbreak of war in September 1939, could be stated as having a quite accurate picture of the air armament, deployment, and strength of foreign air forces, as well as their organization and expansion.[22] This intelligence enabled the German Command to quickly defeat the Polish and French Air Forces during the first phase of the war. It also permitted the Chi-Stelle closely to follow the activity of the Royal Air Force (RAF), even after the commencement of hostilities, when the use of efficient cipher systems was immediately adopted.[22]

When war began, each of the Referats (departments) dealing with foreign countries had compiled an opulent background of material on the foreign air force with which it was concerned. The quantity of this material constantly increased, and was studied carefully. Each Referat maintained close contact with its corresponding sub-section in the office of Ic (Operations), with these, in turn, lent the Chi-Stelle the benefit of their records and experience. The Referat exercised influence over the operations of the Intercept stations. On the other hand, preserving elasticity and processes in the conduct of operations was rendered more difficult by the profusion of Chi-Stelle and Intercept units activated at the start of World War II.[22]

Chi-Stelle

Organisation

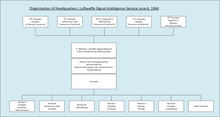

In the beginning of 1938, a reorganisation of the Chi-Stelle took place. Referats (departments) were created to correspond to the subsections within the office of the Luftwaffe High Command. Thus they were newly formed or reorganised.[23]

- Referat A: Personnel, radio equipment of other countries, procurement of radio equipment, and liaison with the Luftwaffe Procurement Division.

- Referat B: Great Britain

- Referat C: France and Italy

- Referat D: Soviet Union, Poland, Czechoslovakia and the Balkans

- Referat E: Cryptanalysis

- Referat F: Direction finding (D/F) Evaluation. Referat F disappeared from the organisation in 1940, as common D/F evaluation of two countries in such widely different stages of radio development as Great Britain and the Soviet Union proved to be absurd.

With the exception of a few insignificant changes dictated by the military situation, this organisation remained effective until the end of World War II. Progressive planning and innovation took place within the other Referats. After the outbreak of the war, the Referats were brought up to company strength fairly quickly, while the Chi-Stelle itself was elevated to the status of a battalion within the signals regiment serving Luftwaffe HQ.[24]

1940-1941

Referat A

Immediately following the start of the Polish campaign, the Chi-Stelle moved from Berlin to the Marstall (Munich Residenz), the former riding academy of Frederick the Great. The Marstall became a sort of second name for the unit, since it remained there until just before the German collapse. In other respects the first six months of the war brought little change to its ministerial methods of working, or its relatively extravagant manner of existence. Only by the middle of 1940 did the newly inducted military personnel gain ascendancy over the civil service employees in the Marstall.[25] The development of the signals battalions assigned to the Luftflotte had been exploited primarily from the military point of view. Since even the signals companies assigned to the individual Fliegerkorps worked independently of the (German: W-Lietstellen), molding their individual activities to conform to the requirements of the combat units they served, the decentralisation of Chi-Stelle at first seemed to be very far reaching.[26]

Thus in the opening phase of the war, the importance of the unit was sharply reduced. The tremendous expansion within Chi had resulted in the employment of untrained personnel, made up in part, of radio operations from the Luftwaffe Signals Corps and in part linguists from other Luftwaffe units who had been transferred into Chi. The intercept stations were placed on their own, and had to be prepared to meet the demands made of them. In addition, teething problems presented themselves during the first months of the war, with types of problems that were never conceived during peace-time.[26] For these reasons, the focal point of the Chi-Stelle quite definitely shifted to the W-Leirstellen, and to those intercept stations which were especially favorably situated and capably commanded, considering that Chi-Stelle itself was scarcely more than an administrative office.

To meet this development, the unit expanded its Referats to an extent such that by the end of 1940, the referat were almost as large as the Leitstellen. Owning solely to its relations with General Staff, it took operational control of the Leitstellen, and requests for personnel or equipment by the Leitstellen had to be approved by the Chi-Stelle. In this manner, it remained the central organisation and administrative unit of the Luftwaffe Signals Intelligence organisation. Through this mechanism it remained in constant touch with all Chi-Stelle problems and this was especially true during the first period of the war, when it was accustomed to maintain direct contact with the Leitstellen as well as each Intercept station.[27]

- Operational Planning: This section dealt with all planning for monitoring operations on each of the fronts. This section also prepared organisation and equipment tables and the allocation of personnel to e.g. Intercept outstations. In view of the rapid expansion of the section at the beginning of the war, this was considerable task.

- Personnel: Routine personnel matters relating to the whole section.

- War Diary: An officer maintained the official War diary of the Chi-Stelle.

- Research: Captured equipment was examined, repaired and put into general use. Liaison was maintained by the technicians to the Luftwaffe Office of Technical Equipment.

The management of Referat A was not subject to much change. Some personnel accompanied the Chi-Stelle Chief to the Luftwaffe Advanced HQ on the Eastern Front, but the technical research section remained in Marstell. Personnel of this Referat were mostly civil service employees with a small mix of military officers and enlisted men.[28]

Referat B

During the interwar period, Referat B had compiled what it considered excellent records of the Royal Air Fore. It possessed knowledge of the organisation, including locations of airfields, strength of units, types of aircraft used, and a complete understanding the RAF supply chain. After the outbreak of the war, Great Britain began to encipher its radio communication, making it became harder to maintain the overall picture of the RAF. Thanks to documents captured in the first days of the war, RAF reconnaissance messages could be immediately decoded. This resulted in the creation of an tactical evaluation section which would work in closest cooperation with the Kriegsmarine and B-Dienst.[29] During this period Wireless telegraphy section was working to annihilate the RAF Fighter Command.

Before the conquest of France, W-Leit 2 and its several out stations had supplied the Referat for intercepts for evaluation. After the occupation of France, W-Leit 5 with outstations, was established in Oslo to monitor Scotland and the northern section. W-Leit 3 which had originally been used in the Battle of France, was transferred to Paris to monitor the RAF. The Referat was now performing the final evaluation of intercepts from the work of three SI battalions. The attention of the High Command was devoted solely to the war in the West.[29] This was indicated by the transfer of a substantial part of the Luftwaffe General Staff to France in September 1940. In October, they were joined by the HQ of the Chi-Stelle and Referat B, which at the time was the most important section in the unit. For the Chi-Stelle staff, the placement in Paris was a short duration, as they returned to Marstall in December to plan the preparation for Operation Barbarossa. Referat B, however, remained at Asnières-sur-Oise until the Allied breakthrough by the Americans at Avranches forced the unit to withdraw from France.[30]

The move to France had a very considerable effect on the work of the Referat. Its location in the vicinity of SI battalions and Intercept out-stations made for excellent cooperation. The setting in the Paris locale, enabled Referat B to adapt its work to meet the tactical and strategic requirements of the war situation. The increasing amount of intercepted material resulting from the intensive monitoring of Great Britain meant an increasing amount of personnel, and by mid 1941, it had reached 60 men. The new military personnel were often excellent linguists or translators and the idea of the old civil service employee was fading.[31]

During this time, Ferdinand Feichtner, who had had started training W-Leit 3 staff at the Chi-Stelle Academy in Söcking, was appointed Chief of Referat B. Feichtner who was supported by Colonel Gosewisch of General Wolfgang Martinis office, made certain that the Referat maintained its position in the subsequent reorganisation of the SI unit, that was made necessary with the withdrawal of W-Leit 2. Feichtner then completely reorganised Referat B internally, in regards to personnel and division of work, e.g. the best evaluators were used to create a final evaluation section to prepare for the newly-introduced monthly reports. Feichtner also created a navigational aids evaluation section.[32]

During the first half of 1941, an SI company was activated in Asnieres as part of the Chi battalion. It was composed of three platoons:

- the first comprised the personnel of the Referat.

- the second was cryptanalysts who were moved from Paris to the area to work in the Referat.

- A large W/T intercept platoon, was placed in a neighbouring village in the summer of 1941 to monitor traffic from the United States, using a special Antenna that was erected for this purpose. This company had an average strength of 400 men.

In contrast to the SI battalion, where administrative and operational command had very early had been subordinated to the battalion commander, these two function remained segregated in the Chi-Stelle until the end of the war. This may have been done to ensure the Referart's chain of command greater freedom of action, compared with other commanders. From the viewpoint of the enlisted me, many incidents, especially at the start of the war, arose from the strained relationships between military commanders and their superiors in the Referat. However, within the Chi-Stelle, the polite atmosphere of higher command was always maintained.[33]

Referat C

After the Chi-Stelle regorg in 1938, Referat C became responsible for French and Italian traffic. Owing to the change in German foreign policy, monitoring of Italy gradually dwindled, until Italy joined Germany in the Axis and declared war on France on 10 June 1940. The interception of radio traffic from Italy was then forbidden by Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring. From then on, Italy was monitored clandestinely and without the knowledge of Göring. The interception of French traffic by W-Leit 3 was bore excellent results. A regular supply of reports sent by Referat C to the General Staff and French Air Ministry documents captured by the unit, bore testament to this. After the completion of the Battle of France on 25 June 1940, the work of the Referat was terminated, taking over a year to wind down.[34]

From the start of the war, RAF overseas R/T traffic was monitored by Referat B. In the spring of 1941 and after the Balkan Campaign, the Luftwaffe started to use bases in Italy, for participating in the Battle of the Mediterranean, with a plan to establish a number of intercept stations. Accordingly, this small sub-section, that had increased in size to three men, was recalled to the Marstall in May 1941. This small groups was to be the nucleus of a final evaluation centre for RAF Mediterranean and Near East traffic. For this purpose, it was increased in size by the addition of English speaking translators and evaluations from the French section. Due to the long distances between Potsdam and the Italian Intercept stations, combined with personnel problems, it was a long time before the Referat C could produce radio intelligence.[35]

Referat D

During the interwar period, Referat D evaluated traffic intercepts from the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, Poland and the Balkan States. From 25 June 1940, after the other nation states had been conquered, the Referat worked exclusively on Soviet Union traffic, which had been considered of prime importance from the beginning. The development of section was different compared to other Referet, due to the different structure of the unit in the east. Whereas in the west and south, cryptanalysis had been abandoned to an extent, with the main focus now being traffic analysis and W/T evaluation, in the east, the majority of enciphered messages could be read. Another fundamental distinction, was that in the west, the Allies emerged with a new or revolutionary radio or radar technique, while in the eastern theatre brought relatively few technical innovations. During the course of the war, the Soviet air armies developed their own particular radio procedure.[36]

Referat D was initially stationed in the Marstall, and at the end of 1941, moved to Ruciane-Nida (Niedersee). In spring 1942, it moved with the General Staff, in preparation of large scale operations in the southern section, to Žitomir, where it was stationed until May 1943. It retreated to Warsaw at the beginning of 1944, where it established a Meldekopf, that was incorporated into the Command Post for Radio Evaluation (German: Zentraler Gefechtsstand für Funkauswertung) (ZAF). After Soviet troops overran Minsk, and began to threaten Warsaw, it moved to the university city of Cottbus. Towards the end of 1944, it merged with the regimental evaluation company of SI Regiment, East.[37]

Organisation

Referat D only sent reports directly to General Staff only during the first two years of the war. At the end of 1942 a liaison team was established in the operations office (Ic) to deal with intercepts originating in the East. The reports produced by the section were highly specialised and essentially unintelligible to the non-specialist, so they were rewritten by the liaison team. The team had 10 members, who were generally highly qualified. The Referat had a large cryptanalysis platoon attached to it, consisting of around 90 men at the height of the war. But its importance dwindled in the last years of the war, as Soviet cryptographic systems became ever more individual in character and centralized cryptanalysis of the intercept was found to be impractical.[38]

Also attached to the unit was a large radio intercept platoon which monitored point-to-point networks in the Soviet Union rear defence zones. An intercept company located in Rzeszów forwarded intercepts by teleprinter to the Referat, who sent them to the cryptanalysis platoon to be deciphered. The second main source of the reports was teleprinted summaries from three intercepts in battalions in the east. From 1943 onwards, R/T traffic from Soviet tactical aviation units increased in significance, even being important to final evaluation. During the latter years of the war, it was particularly important on the northern sector where the availability of good landline communications limited the use of radio.[39]

Meldekopf Warsaw

The Meldekopf in Warsaw consisted of a team of 10 specialists. As Soviet long-range bombers were active only at night, both its radio operators and evaluations alike were only occupied at night. The unit intercepted traffic on all known bomber frequencies and was reported to the nearest ZAF as an early warning. The Luftwaffe considered neither the radio discipline nor the navigation of the Soviet bomber crews to be comparable with the Allied crews in the west. The Meldekopf would report to the ZAF, and to other appropriate HQs, the exact strength, composition, and probable target of enemy bomber formations. This information was determined around the time the Soviet bombers were cross the front lines.[40]

Referat E

For the initial development of Referat E, i.e., supposed cryptography section, started from October 1935 until early 1939, when interpreters and translators that were newly employed by the German Ministry of Aviation were sent to fixed intercept stations of the German Army in Königsberg to monitor the Soviet Union and Baltic states, Treuenbrietzen to monitor the Soviet Union, Breslau station to intercept Czechoslovakian and Polish traffic, Munich for Italian traffic, Stuttgart for French traffic and Münster for monitoring traffic in Great Britain. After a period of training, they were assigned to Luftwaffe SI stations.[41]

Instruction in cryptanalysis was not provided for, nor did it take place. It was known that several civil service employees has contact with personnel within the field of cryptography and through this became familiar with its general outline. After the formation of the Luftwaffe Chi-Stelle was created in 1939, Referat E was formed and became responsible for all cryptanalysis within the unit. In October 1938, a 4-week training course was established in Berlin for the study of cryptanalytic methods in the west. In spring 1939, a similar training course was instituted for the east, and evaluations from the fixed intercept station were ordered to attend.[41]

When World War II started, the Chi-Stelle had 15-18 decipherer's, 10 of whom were familiar with the cryptology techniques used by the Allies, but none could be rated as an excellent cryptanalysts. These men were all eventually removed from the unit. Instead to assist in the work, that was now plentiful in nature, the Chief Signal Officer assigned 50 newly inducted enlisted men to Referat E, none of whom had, had any previous training in cryptanalysis. The personnel learned their trade in practical experience rather than in theory.[41]

The development of the Referat worked by exploring in detail a new difficult cryptographic procedure while stil in the Marstall, and then exporting that deciphering process to those intercept battalions or companies where the greatest amount traffic was being intercepted. In this manner, Referat E personnel were eventually stationed all over Europe.[42]

The Referat expanded continually and by the end of 1942 reached its peak strength of approximately 400 men. Later policy by the German High Command meant the unit was stripped of physically-fit men for use in combat units with replacements being women auxiliaries, caused the ongoing cryptanalyis to suffer a set-back. However, the more important systems were still solved up to the very end of the war, and even in the month of January 1945, the unit solved 35000 message intercepts in the west, and 15000 in the east.[42]

The chief of the Referat Ferdinand Voegele was an Inspector-Technician (German: Inspektor-Techniker), who until 1943 had no assistants who were officers, even though he was continually compelled to visit Intercept stations in the course of his work. An ongoing difficulty in the work of the referat, which continually manifested itself, was that it had no influence on the number or location of intercept receivers covering traffic in which it was interested.[42] This often caused delay and in some cases stalled the cryptanalysis pipeline or made it impossible.[43]

Training

After a few hours of instruction, novice Luftwaffe cryptanalysts were promptly put to work, the solving of which was in various stages of advancement. After a few weeks the novice was then shifted to a new procedure, as part of a mechanical process in a manner that would enable them in time to learn the different methods of solution. The emphasis was on breaking a cypher or code quickly, with matters of theory of secondary importance.[43]

The advantage of this method was that individuals could learn in the shortest possible time to successfully decipher certain well known systems such as the Bomber Code and the British Main Weather Code. However, these cryptanalysts failed completely when attempting to break a simple, alphabetic, unrecyphered 3 or 4-digit codes, even if an ample depth was available. The long duration of the war, gradually reduced this disadvantage since each analyst eventually had the opportunity of working of entirely different systems.[43]

In general, experience showed that men over the age of 35 years, made for below average cryptanalysts. Professional people, like academics, e.g. mathematicians and Philologists, with individual exceptions proved unsuitable for practical deciphering work. As a rule, they exhausted themselves in laborious analytical research, only to find later that the cypher or code had already been solved. The best results were achieved with young people who had completed their high school education or had just entered a university.[44]

1942-1945

General

The great widening of the battle front and the prodigious expenditure of men and material forced the German Command, following the first grim winter in the Soviet Union, to adopt radical economy measures. Thus, the Luftwaffe Signal Corps, that had suffered relatively slight losses, was referred to the pool of women workers for its replacements, as the men were being striped from Luftwaffe units for the front.[44]

The importance of radar intercept, moreover, that by the middle of 1942, had finally become production ready, had become decisive to the development of the chi-stelle in the west and caused significant structural changes. At the same time, as German strategy swung to the defensive, the chi-stelle emerged as the most reliable source of radio intelligence. As the Allied air offensive unfolded, its importance to the defense of Germany became apparent, not only to the High Command, but to tactical headquarters as well, and from then on, both were concerned that its organisation become optimal. From the beginning of the war, command of the Chi-Stelle unit had changed hands frequently, with unsatisfactory leaders.[44] The Luftwaffe General staff officer Ferdinand Feichtner who was considered to have an excellent reputation with the General Staff, took command of the unit in February 1943.[45]

At the same time the Chi-Stelle, at least in the west, was freed from the administrative management of the signal regiments of the Luftflotten by the creation of an independent Signals Intelligence regiment. This regiment had three battalions, one of which was devoted exclusively to radar intercept. This stronger centralisation had a favourable effect on future development. The number of impediments to which a relatively young branch of the service was inevitably subjected was considerably reduced by the excellent relations between the Commanding Office of the Chi-Stelle and the General Staffs.[46]

At the end of 1942, the Radar Intercept Control Centre was created in Eiche for the central evaluation of the results of radar intercept. Radar intercept centres were also brought into being at the same locations as the W-Leit of the Luftflotten, and gradually within the boundaries of Germany itself. Chi-Stelle determined policy, and planned the expansion of the Radar Intercept Service, while the development of processes was left to the out-stations and the commanders of the Referat. In this aspect, Chi-Stelle purpose was essentially one of administration and supply.[47]

The Chi-Stelle from 1943 was no longer distinguished by creative ideas. The choice of an officer with no signal or intelligence training as Director of so highly specialised a service was not a fortunate one. Briefing of the General Staff was the direct function of the Referat. Each Referat chief, in proportion to his ability, made the influence of his Referat felt on the evaluation work of his respective Leitstelle. Except for personnel and administrative matters, those Leitstellen which were capably commanded were completely independent of the Chi-Stelle. An example of this separation of concerns, was that many times they even procured special signal equipment or communication facilities from the tactical units they served, rather than go through the normal Chi-Stelle channel.[48]

The Chi-Stelle also failed, when the time was right, to mold the unit into a comprehensive and exclusive organisation with its own military standards. On the contrary, in the autumn 1944 when signals regiments were formed in the west, south and east, bureaucracy intervened to create two extraneous posts. The first one was an Signal Intelligence Director for administrative matters, the second new post was that of Signals Intelligence Leader (German: Funkaufklärungsführer Reich), pertaining to the defense of Germany.[49]

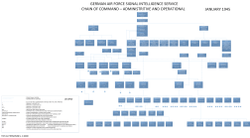

Organisation

The structure of Chi-Stelle was essentially the same since the beginning of the war, and had developed along two main lines. Tactical evaluation from 1943, had become predominant and had resulted in the establishment of early warning and flight tracking systems.[50] The development of tactical evaluation was fostered by the increasing strength of Allied air raids on both the occupied countries and Germany, and it far exceeded the importance of strategic evaluation. This work culminated in the creation of the ZAF [Ref 3.2.4], a central Meldekopf for the defense of the Reich.The Chi-Stelle remained both indifferent and helpless in the face of this development, with the result that the position of Chief Signals Intelligence, a parallel headquarters had to be created to manage signals matters pertaining to Germany. Secondly, the unification of the Chi-Stelle, that by 1942 had expanded into an organisation of division strength and was urgently in need of an independent administrative system in consideration of its special function, finally in 1944, proved most necessary. Discussions to solve this problem had begun in 1941, but postponed continually.[51] However, since Chi-Stelle planned and supervised all signals intelligence operations from the beginning, it could easily acted as its own central administrative authority. In the spring of 1944, the first of these reorganisations took place. All signal intelligence units, including the Chi-Stelle which previously had been under the command of the Ministry of Aviation were now placed under the tactical command of the Chief Signals. 3rd Division, Lt. Colonel Ferdinand Feichtner whose rank was (German: Generalnachrichten Führer) (General Nafue III).[52]

This centralisation in tactical matters and the decentralisation in administrative affairs to the field command units, led to difficulties in guidance and supply. As a result, in November 1944, after an abortive order by Hermann Göring to unify all Luftwaffe signal intelligence units through combining all listening, jamming and radio traffic units as part of Air Signal Regiments, a new comprehensive organisation was finally created.[52] This new organisation unified all home and field units into independent air signals Regiments and battalions with unit numbers ranging from 350 to 359. Administration was centralised and subordinated to a Senior Signal Intelligence Officer, Generalmajor Klemme, a veteran signals officer, who held the position of (German: Höherer Kommandeur der Luftnachrichten-Funkaufklärung).[52]

From 1941 to 1944 the signals intelligence battalion in the Marstall consisted of:

- A company in the Marstall which comprised the personnel of Referat A, C and E.[53]

- A company in Asnières-sur-Oise comprising the personnel of Referat B, part of the personnel of Referat E and an intercept platoon.

- A company in Žitomir, later Warsaw comprising personnel of Referat D and a large intercept platoon and Meldekopf.

- A company in Munich, Oberhaching comprising personnel of Referat B5 and an intercept platoon to monitor the United States.[54]

- An intercept company in Rzeszów which monitored Soviet point to point traffic.[55]

After the withdrawal from France, the company in Asnières-sur-Oise was dissolved and Referat B greatly reduced in personnel, was migrated into the evaluation company of signals intelligence regiment west. The company in Rzeszów which had moved to Namslau in the middle of 1944, was transferred to the signals intelligence regiment east, and for practical purposes it already belonged. Referat D was incorporated into the evaluation company of this regiment when the latter left Cottbus and retreated to the southwest while under attack from the Soviet advance. In February 1945, the Marstall was abandoned.[56]

In the autumn of 1944, the Chi-Stelle battalion, as had been the case with of all signals intelligence battalions, became independent of the Luftwaffe Signal Corps Regiment to which it had been assigned. Command was taken over by a captain who was given the prerogatives of a regimental commander. It was renamed Air Intelligence Department 350 (German: Luftnachrichten Abteilung 350) and retained its previous function of planning for the entire Luftwaffe signals intelligence infrastructure. In reality, the command structure, and unit organisation had not changed at all, in spite of the battalion commander, Captain Jordens, the administrative chief, General Klemme, and the Funkaufklärungsführer Reich, Colonel Forster, Lt. Colonel Ferdinand Feichtner as the representative of the Chief Signal Officer, remained the supreme until the end of the unit.[57]

Liaison

The Referats were the supreme authority on all evaluation questions arising between the regiments, battalions and the Chi-Stelle. They furnished intelligence directly to the General Staff where an liaison officer had been assigned since 1942.[58] Section II of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer only had communication with individual units insofar as to pass them orders. The final preparation of reports decided by Referat. The responsibility for distribution of the reports was decided by the Chi-Stelle Director who acted in consultation with the Chief Signal officer.

Liaison with B-Dienst, the Kriegsmarine cipher bureau and General der Nachrichtenaufklärung, the German Army cipher bureau, as well as the Radio Defense Corps was carried out at both the level of the Referat and at the Leitstellen, which exchanged reports with Navy and Army cipher bureaux located in their respective areas. However, owing to the extreme secrecy which surrounded all activity at the unit, the process of exchange was not perfect. For example, the close and happy liaison between the Luftwaffe and the Radio Defense Corps regarding partisan activity (Yugoslav Partisans) in the Balkans was founded on the relationship between two Leutnants, who despite instructions to the contrary, exchanged intelligence on this subject.[59]

The three cipher bureau (German: Chiffrierstelle) exchanged reports, and in the case of the Luftwaffe, these were studied by the individual Referat. From 1942, a liaison officer from Referat B was assigned to the Army Chi-Stelle in Saint-Germain-en-Laye but no special benefits were derived from this close association.[60]

Chi-Stelle decided the extent of co-operation and liaison between Germany's allies, but the execution of process was decided by the signals intelligence units located in the various countries.[61]

The Finland cipher bureau, the Signals Intelligence Office (Finnish: Viestitiedustelutoimisto) was the only bureau that compared with Germany in terms of quality had made excellent progress on the cryptanalysis of Soviet (Russian) systems.[62]

Liaison with Japan did not exist, and contact with the Japanese on air signal intelligence could only take place through the General der Nachrichtenaufklärung, that received the monthly reports of the unit. It would seem probable that the Japanese signal intelligence bureau would be interested in reports of special fields, such as the 8th USAAF or Allied navigational procedures, would have been furnished by the GDNA. In the last year of the war, and at the request of the Japanese, it was intended to send a German mission, comprising medium frequency and High frequency specialists of the Luftwaffe, Heer and Kriegsmarine to Japan. Strangely the Japanese were not interested in VHF or radar interception and jamming. Planning for the trip was organised by Major Mettich and Captain Grotz, who were both subordinated to Colonel Hugo Kettler, who was in command of OKW/Chi. However, the plan never materialised.[63]

Referat A

When the Chi-Stelle was taken over by General Staff officer, Ferdinand Feichtner in the spring of 1942, it resulted in the Lietstellen being supported in a previously unaccustomed manner.[64] In order to meet the increasing demands within the unit for personnel and equipment, the Chi-Stelle initiated a strict management control policy. the development and procurement of radio receivers was also problematic and involved negotiations with the manufactures, who with long supply chains, demanded notification of orders long in advance. Problems with personnel bounded, with the personnel officer whose only experience was the Eastern Front, while Friedrich's staff didn't have one officer who had experience of working against the Anglo-American Allies.[65] Therefore, the Chi-Stelle command had little understanding of the problems existing in the west and south. The problems were compounded by individuals who lacked tactical experience, particularly Captain Trattner, Commander of Radar Intercept at LN Abteilung 356, who was a professor of electronics. It can be stated that Referat A had a short-sighted policy as regard to personnel, as well as an indecisive and dilatory manner when it needed to handle personnel problems affecting the entire unit.[65]

Referat B

General

In contrast to other units and sections of the Chi-Stelle, Referat B maintained a constant and purposeful policy towards its own personnel. When the former Director of the unit was ordered back to the Marstall in mid-1942, his place was taken by a career officer who removed the last vestiges of the civil service regime from the Referat.[66] Daily conferences and a number of experienced combat officers were brought in and employed to advise the evaluations in the various desks. The personnel of the Referat was now continuously trained, and were accorded all privileges possible with military functions, such as drilling kept to the minimum. As a result, morale in the unit was considered excellent.[66]

At the end of 1942, some of the personnel was replaced by women auxiliaries. Shortly before the Normandy landings, the Referat consisted of 4 officers, 3 technicians, 45 enlisted me, and 25 auxiliaries.[66] After the withdrawal from France in August 1944, the Referat was merged with the evaluation company of Signal Regiment West. Personnel was reduced by more than half. At the end of the war, with the advancing Allies, the unit moved to Türkheim in Bavaria when it was subsequently dissolved.[66]

Organisation

Allied traffic intercepts increased significantly when the RAF expanded from 1942 onwards, and the arrival of American Air Forces in the British Isles.[67] This resulted in a reorganisation of Referat B, which was gradually implemented during 1942. Later the desks of the Referat were organised to correspond to Allied air unit categories, rather than types of radio traffic. The organisation was as follows:

- Technical evaluation section which evaluated RAF Coastal Command intercept and during the Normandy landings and with air support, evaluated intercepted party traffic.

- Bomber evaluation section, divided into Royal Air Force and United States Army Air Forces desks, which were concerned with the strategic evaluation of this traffic.

- Captured documents, captured signal equipment and navigational aids, evaluation sections.

- Tactical air force radio traffic evaluation desk.

The Referat has its own mimeograph and technical drawing section. The teleprinter and telephone section was operated exclusively by women.[68]

Evaluation

Referat B was the senior evaluation agency in the west, and evaluated all the work of the signal intelligence units employed in the west and the north.[69] This consisted of:

- Luftnachrichten-Funkhorch-Regiment West that later became LN Abteilung-Regiment 351

- LN Abteilung-Battalion 357

- LN Abteilung-Battalion 355

The Referat worked with reports forwarded to it from intercept and evaluation companies, and also with the original log sheets and messages. The latter method was used for Radio telegraphy, as the spoken word was always open to interpretation. The material available to the Referat consisted of the following:

- Daily reports from evaluation and some intercept companies, that were sent by teleprinter and in some most cases by radio or courier.[69]

- Technical and evaluation reports which the intercept companies prepared monthly.[69]

- Wireless and Radio telegraphy log sheets.[69]

- Prisoner of war interrogations' reports, reports on captured documents and kit. Reports on BBC broadcasts and other collateral intelligence material. This interpolation of this material was strictly forbidden, and when used, a reference was provided to the source and if this was missing a reprimand from Ic operations to the Referat chief resulted. It was provided to bring a richer background to intelligence reports.[69]

It was advantageous that personnel of Referat B belonged to Chi-Stelle as intelligence could be report or when necessary refused to be divulged under certain conditions without reference to rank or station. The last two chiefs of the Referat were adroit at using their position to maintain a close check on the evaluation work in the west.[70] Duplication of work between Referat B and Luftnachrichten-Funkhorch-Regiment West was an ongoing bureaucratic problem and the only considered solution was the merging of the two units, but it was only realized as the result of Allied pressure, when both Referat B and Luftnachrichten-Funkhorch-Regiment West, following a breakthrough by the Allied at Avranches as part of Operation Cobra by the United States 1st Army, retreated from France. Owing to the difficult housing situation within Germany, the Referat and the evaluation company were established in the same house in Limburg. For each case arising, a discussion took place as to whether a special report or appreciation would be written by the Referat or the specific company from Luftnachrichten-Funkhorch-Regiment West.[70]

Direction of Intercept operations

Outside of final evaluation, the direction of intercept cover in the west and north was the most important task for the Referat. All intercept stations understandably had the desire to monitor only that traffic which yielded results.[70] The referat had to insure that not only was this traffic covered, but also those frequencies necessary to obtain a correct intelligence estimate.[70] For example, several intercept companies could only be moved under pressure to monitor point-to-point networks of the RAF and the Allied Expeditionary Air Force, as no tactical messages that could be reported to combat units were intercepted on those networks. However, these networks still had to be monitored, as it was necessary to understand the organisation of Allied air forces.[71]

With the appearance of new allied units which needed to be monitored, intercept companies found it difficult to burden themselves with the intercept requirements of the new allied units. In that instance, Referat B would intervene, and reorganise the intercept and evaluation companies accordingly, as per need and personnel available.[71]

In many cases Referat B itself would take over the analysis of new traffic, and only then would they subsequently assign it to the appropriate evaluation company.[71]

Messages and Reports

The most important headquarters to which the Referat reported were:

- The Luftwaffe General Staff, Oberkommando der Luftwaffe.[71]

- The Chief Signal Officer of the Luftwaffe, Ferdinand Feichtner.

- The General der Nachrichtenaufklärung, the signals intelligence agency of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht.

- The B-Dienst, the German Naval Intelligence Service of the Oberkommando der Marine.[71]

- Luftflotte 5

- Referat C, for those units working in the south.

In many cases reports were also sent to the commander west, Luftflotte 3 and NAAS 5 of Army signals intelligence regiment KONA 5.[71] The following types of messages and reports were involved:

- Flash reports of important new discoveries, enemy movements of Allied units, that were sent by telephone and teleprinter.[71]

- A 24-hour daily summary report.[72]

- Monthly reports comprising 50-60 typewritten pages of exhaustive treatment of all events and developments during the month, complete with maps and illustrative diagrams.[72]

- Special reports, e.g. on Army-Air Force collaboration during manoeuvres in the Great Britain.[72]

Moreover, all important information found in captured material was communicated to individual signals intelligence units. The latter received from Referat B all necessary data such as lists of X and Q groups, lists of frequencies, Call signs, abbreviations and so on.[72]

Referat B5

In 1941, a section within Referat B was established to monitor and intercept traffic from the United States. This in turn was divided into two desks. One desk analysed traffic which was related to United States Army Air Forces, the other to United States Navy air forces, which at the time were being hastily built up. Traffic from America was ready from intercept stations in Germany, France and Norway. The desk reached its peak in late 1942, early 1943, when new equipment was becoming scarce and this dictated a more conservative use of radio receivers. The second section desk intercepted air ferry traffic on the North Atlantic route, in connection to RAF Coastal Command. The Atlantic traffic was monitored by Referat C until 1942, when it reached peak importance. As the war progressed, and United States cryptography steadily improved to an extent it could no longer be read, Referat B took responsibility of this South Atlantic commitment from Referat C.[72]

As Allied air ferry traffic increased in importance it was decided to detach the desk from Referat B in mid 1943, and move it into its own section. Specialist personnel from Referat C were moved to Oberhaching and the new section was renamed Referat B5.[72] At the same time a large wireless telegraphy intercept platoon that belonged to the Marstall battalion, was moved to Oberhaching and attached to Referat B5 to take over monitoring of air ferry traffic except those on North Atlantic route, which were covered by the 16th Company of Lichtenstein Regiment (LNR) 3 in Angers.[73] The new Referat evaluated all air ferry traffic, e.g. Morse code, Baudot code, and had the following responsibilities:

- The monitoring of the United States, which only touched the surface of the traffic, still furnished insight into the principal networks of the Army and Naval Air Forces, into training activity, air transport, defence zones, and the activation of new combat aviation units.[73]

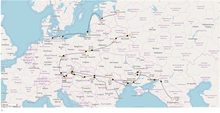

- The monitoring of Atlantic air ferry service. The middle and central Atlantic routes were monitored by the W/T platoon in Oberhaching and by Luftwaffe signals outstations in Spain, which operated under the cover-name of Purchasing Agencies (Fig 3). The North Atlantic route was monitored by the 16th Company of LNR 3 and reported furnished to the Referat.[73]

- The monitoring of the United States Air Transport Command by the platoon in Oberhaching.

- The monitoring of the RAF Transport Command and both USAAF and RAF troop carrier commands. The greater part of this interception was also carried out in Oberhaching.[73]

Airfield radio traffic, transmitted on 6440 Hz was intercepted in Madrid, Montpellier and at various outstations in the Balkans and Italy. This traffic was evaluation by Referat B5 with the aid of an extensive intelligence library encompassing charts, diagrams, directories, manuals, maps, phone directories and so on.[74] Referat B5 also had a small cryptanalysis section of its own, which deciphered intercepted messages on the spot.[74]

Referat B5 remained operational until the last weeks of the war, and was in a position to cover the British airborne landing at Bocholt.[74] One week before the capture of Munich by the US 20th Armored Division. US 3rd Infantry Division, US 42nd Infantry Division and US 45th Infantry Divisions, the male members of Referat B5 withdrew to the Alps, while its women auxiliaries were discharged.[74]

Referat C

General

When the importance of the Mediterranean theatre increased in the middle of 1942, the totally incapable director of this Referat was relieved from office at the instigations of General Staff operations, and replaced by the director of Referat B.[74] At the same time, several experience evaluations were transferred to Referat C in order to mentor and assist new staff and this served to increase morale in the unit. In general, the operational methodology of the unit was similar to units in the west.[74] In spite of wire communication to Sicily and Greece being considered reliable, the great distances to the Mediterranean theatre presented problems. Tactical evaluation was lacking and daily reports were always 2 days behind schedule.[74]

Referat C was considered unproductive, inefficient and bureaucratic. During the entire period of its existence it failed to produce a single technical or special report, in spite of the fact there was sufficient material from was activity in the Mediterranean area. In early 1943, the number of personnel in the agency was increased with 20 women auxiliaries, with the emphasis shifted entirely to paper work.[75] During this period the agency was completed detached from problems in the Mediterranean area.

This condition became worse in 1944-1945 as duty hours were increased, rations became viewer and bombing raids became more frequent. The prevalence of political sycophants, the threat of being sent to the Eastern Front, the threat of transfer via disciplinary action, all served to suppress and curb the agency personnel working 12 hours or more a day. Messages and reports from the retreating signals units in the south became scarcer and scarcer.[75] After the formation of Luftnachrichten Abteilung 352 in spring 1943, a merger of the Referat and the regimental evaluation company was considered, but never carried out. In February 1945, the unit disbanded, with parts of the unit travelling to Premstätten in Styria and later in Attersee. Although reduced in size, it started to function again under command of a new energetic director. However this was short lived and in May it ceased activity.[75]

Organisation

Referat C was organised into desks which corresponded to Allied units or activities, e.g. Mediterranean Allied Tactical Air Force (MATAF), 205 Group RAF, long range reconnaissance, radar reporting networks, transport and ferry service, airfield radio tower traffic.[76] In addition, two other sections, one devoted to press reports and prisoner of war intelligence, and other to point-to-point networks were especially successful. The two sections, in close co-operation, maintained a detailed organisational plan of Mediterranean Allied Air Forces(MAAF), that the Luftwaffe operations office included in its monthly reports.[76]

The following desks were attached to Referat C:

- Turkey. 3 men revised and edited the material intercepted and evaluated by W-Leit South-east, and prepared weekly and quarter-yearly for operations.[76]

- Sweden and Free France. Monitored by outstations with monthly reports were forwarded to operations. After the German withdrawal from France, the desk was reintegrated to Referat B.[76]

- Referat C2. This section was created in 1942, and was engaged in preparing a textbook on the radio, navigational procedures and Call signs of the Royal Air Force, United States Army Air Forces and Russian Air Forces. This textbook has a wide distribution, and all larger signals units were given copies for research. Supplements were produced which kept the work up to date. In mid 1944, the work was abandoned and the personnel transferred to signals outstations.[76]

An intercept station also existed in the Marstall itself, and was manned by linguists from Referat C and E. Its primary function was to monitor and intercept traffic that indicated a bomber read in the greater Berlin area by the USAAF. As the Marstall was responsible for the allocation of VHF receivers, the equipment in the intercept station was the best of its type.[77] The proximity of the Referat proved advantageous, as the R/T technicians manned their sets only during a bombing raid and therefore could devote the balance of their time to either evaluation of cryptanalysis.[77] Flash reports were telephoned to Meldekopf 3 stationed in Wannsee, while final evaluation reports were sent to the ZAF.[77]

Operations

Each morning the teleprinted material arrived during the previous night from the two signal battalions in Italy and the Balkans,[77] from the company in Montpellier, outstations in Spain, and later from the ZAF, as well as from those outstations which were authorized to have direct communication with the Referat. The intercepted material was sorted, categorised by the Referat director and distributed to the appropriate desks.[77] In the course of the afternoon, the desk would check the incoming intercept. If it could be read, it was deciphered, and evaluated immediately. If it could not be, it was sent to cryptanalysis. Deciphered reports were prepared for inclusion in the daily report of the Referat. After being edited by the evaluation officer, the intercept formed the basis for the daily situation conference at which all controversial points were discussed.[77] It was then Mimeographed and around noon it would be ready for distribution. One copy was sent by courier to the General Staff, the others were mailed to the recipients.

The afternoon as a rule was devoted to the study of incoming reports and a review of log sheets in from the units in the field; maps were prepared and preliminary work done on the monthly report, the distribution of which corresponded in principle to that of Referat B reports.[77] Correspondence with the regiments and battalions was taken care of, comments from the General Staff were studied and those relevant were passed on to the field units concerned.[77]

The Referat achieved success in the field of traffic analysis. By means of network diagrams, the organisation of the Allied tactical air forces in Italy was worked out at a time when W-Leit 2, in spite of its greater proximity to the situation and its operational experience with abundant wireless telegraphy (W/T) and R/T reports of XII Tactical Air Command and Department of the Air Force (DAF), was completely helpless.[78] In general, as clumsiness, distrust and dodging of responsibility characterised the leadership of Referat C. In order to keep its surplus of personnel occupied, ridiculous and unnecessary tasks, involving a labyrinth of paper work were created. As a result, all feeling for conciseness was lost. The majority of members of the Referat, in spite of years of service in the Chi-Stelle, had never seen an out-station. This reluctance to face realities, weakened the influence of the Referat.[78] In consequence, its options in organisational matters carried little weight within German High Command, and for most part it was limited to special problems of evaluation.[78]

Liaison

Liaison also was limited to the field of evaluation. Due to the location of the Chi-Stelle and personal acquaintances, especially with Luftwaffe Ic, it was considered excellent.[78] Prior to the daily conference, any new problems and all the material that had come in the previous night, were discussed by telephone between the Referat and the operations office, Ic of the Luftwaffe. The discussions that took place included Allied air transport and the current air ferry situation reported by Referat B5 in Oberhaching.[78]

When United States radio stations appeared on airfields in the Poltava area, as US bombers and fighters escort landed in these airfields, following attacks on Germany or Rumania, an evaluator from Referat C was dispatched to Referat D in Warsaw. A large intercept platoon was transferred to Warsaw to monitor this traffic.[78] However, the results were insignificant and after fourth months the W/T platoon was recalled.[79]

In 1944, the Referat places a liaison officer with Dulag Luft, that resulted in many pieces of collateral intelligence being collected, as well as important confirmation of previously gathered intelligence.[79]

In the last months of the war, the Referat was merged with the evaluation company of Regiment South.

Radio Defense Corps

History of operations in the west

History of operations in the south

Operations in the south

General

While the Luftwaffe signal intelligence in the west reached a higher state of development, it was in the south that it faced its greater challenge. This was true because it faced a foe as equally as aggressive and resourceful, an extremely varied physical environment and geographical extent of the Mediterranean theatre of war, wherein its operations were conducted.[80]

Mid 1941

History of operations in the east

Operations in the east

Luftwaffe operations in the east

General

The overall mission of the Luftwaffe Chi-Stelle on Soviet Front was the interception and identification of the Soviet Air Forces radio traffic.

To accomplish this mission, it was first necessary to determine the types of signal communication being used by the Soviets. For both Wireless telegraphy (WT) and Radiotelephone (RT), the high frequency band was used almost exclusively, the main exception being navigational aids, i.e. radio beacons, which were used on medium frequency. Until the end of 1942, only WT traffic was found, thereafter R/T was also employed, increasingly greatly from 1944 onwards. The Soviets used radar only to a small extent, beginning at the end of 1944. Almost all W/T traffic was encoded or enciphered.[81]

From Germany’s point of view, all Soviet W/T traffic could theoretically have been intercepted in one centrally located station. However, in practice it was found, as is so often the case, that areas of [skip], interference and natural barriers precluded such a plan and led to the establishment of numerous intercept stations all along the front.[81]

Cryptanalytic problems were solved by the use of a relatively large number of personnel, not a few of which were capable linguists and could also be used to translate the contents of decoded messages.[82]

A further problem occasioned by the expansiveness of the front was how to communicate the results of radio intelligence to those units and headquarters which could make the most of. The recipients of such intelligence were the Chi-Stelle, the operations (German: Ic) of the Luftflotten together with their tactical units on the Soviet Front, and the signal intelligence services of the Army and Navy. Therefore, pains had to be taken either to site Chi-Stelle units in the immediate areas of such headquarters or at least in localities where good wire communications was available. Due to the danger of interception, and delays caused by the necessity of enciphering messages, radio was considered only an auxiliary means of communication.[82]

Problems encountered on the Eastern front were of such a nature that axiomatic Chi-Stelle procedures and processes could often not be put into effect as a whole, but instead usually as a compromise solution.[82]

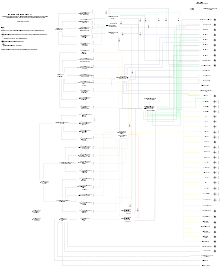

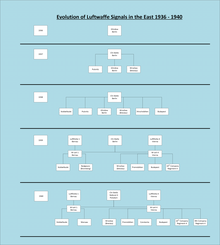

Development 1936 to 1941

Until the invasion of the Soviet Union on Sunday, 22 June 1941, interception of Soviet radio traffic was accomplished by several fixed outstations, each of which was assigned a prescribed area to monitor. In the summer of 1936, the first of these stations was established in Glindow, Berlin.[82] During the year between 1937 and 1938, five further stations were established in Breslau, Pulsnitz, Bydgoszcz, Svetloye (Kobbelbude) and Hirschstätten. Each of these fixed outstations did its own preliminary evaluation work, with final evaluation still undertaken at the Chi-Stelle. The stations were operationally controlled by the Chi-Stelle but administratively by a Luftflotten in whose area they were located. Thus the stations in Hirschstätten and Wrocław were assigned to Luftnachrichten Regiment 4, and the remained with Luftnachrichten Regiment 1.[83]

This policy was a great mistake and remained a point of contention with signals personnel throughout the war. It meant that signals units were subordinated to two unit commanders, and impossible situation from the military point of view. Frequent differences of opinion arose between High Command headquarters, each wishing to be considered as the authority actually controlling the Chi-Stelle. The situation was often intolerable.[83]

It soon became evident that the personnel and equipment available for the monitoring of Russian radio traffic, that was becoming constantly more extensive and complicated, were not sufficient. The Russian methods of assigning Call signs and frequencies became more and more complex. Special complications resulted from the fact that each Russian air army implemented its own signal procedures and cryptography standards, that according to the ability of the individual Russian signals officers, making it either more or less difficult for the Luftwaffe Chi-Stelle. There were some Soviet air armies, that owing to the incompetence or negligence of the signals officers, were looked upon with a sort of affection by the Chi-Stelle, while there were others whose traffic could only be analysed by bringing to bear all the resources that the Luftwaffe had available.[83]

The most difficult task of all was intercepts from the northern sector or lack thereof. This was due in part to the fact that good land-line communications existed in the Leningrad throughout the static warfare in that region.[83]

Owing to ever present personnel problems in the unit, the organisation of the Chi-Stelle unit during 1938 was not significantly expanded in the east. Luftflotten 1 and Luftflotten 4 requested their own signals intelligence unit, and each wished to received signal intercepts directly from the units located in its specified area, and not via the Chi-Stelle.[84] In order to meet these requirements, W-Leitstellen were created in the summer of 1938 in the immediate vicinity of each Luftlotte concerned. It was intended that these Leitstellen render interim reports to the Luftflotten, while expediting the intercepted material to the Chi-Stelle for further processing. The personnel, cryptanalysts and evaluations were drawn from the fixed signals outstations, and to a lesser extent from the Chi-Stelle. This withdrawal of personnel from an already weak organisation suffering from chronic staff shortages caused a deterioration in the unit, without any commensurate gain to the new entities.[84]

In the summer of 1939, the Leitstellen, the fixed stations and the mobile intercept companies on the two sectors were combined into signals intelligence battalions of the respective Luftlotte signal regiments.[84]

When Germany invaded Poland, the Luftwaffe signals units in the east were ordered as follows:

- Referat D of the Chi-Stelle

- The 3rd Battalion of Luftnachrichten Regiment 1 consisted of:

- The 3rd Battalion of Luftnachrichten Regiment 4 consisted of:

- W-Leit 4 in Vienna[85]

- Fixed intercept station in Breslau

- Fixed intercept station in Premstätten

- 10th Company of LNR 4, newly activated and fought at the front during the Polish campaign.[85]

At the conclusion of the Polish campaign, monitoring of Polish communications was discontinued. Its place was taken by the Balkan countries and Turkey, that were monitored from Vienna, Premstätten and Budapest.[85]

In 1940 there were few changes. The fixed intercept stations in Bromberg was moved to Warsaw. An intercept station and DF facility was erected in Kirkenes and the station in Budapest established a satellite outstation in Constanța. A new intercept company called the 9th Company of LNR 4 was activated.[85]

This situation remained static until the invasion of the Soviet Union.

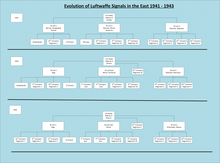

Signal Intelligence Regiment East organisation

Luftnachrichten Abteilung 355 was activated in September 1944. The need on the part of the subordinate signals units for a more unified operational and administrative chain of command was only realised up to the level of regimental headquarters, and then only realised up to the level of regimental headquarters, and then only on paper, as the Chi-Stelle still continued to traffic directly with subordinate units of the regiment.[85] The regiment still suffered from divided control, operationally subordinated to the Chi-Stelle, and administratively to the Chief Signal Officer through Generalmajor Willi Klemme, who was not a specialist administrative officer.[86]

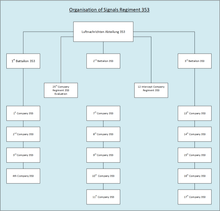

Luftnachrichten Abteilung 353 was organised as follows:

- Regimental headquarters with the 25th Evaluation Company and 12th Intercept Company in Cottbus

- 1st Battalion (north), formerly the 3rd Battalion of LNR 1, with four companies in East Prussia.

- 2nd Battalion (centre), formerly Signals Battalion East with five companies in Poland.

- 3rd Battalion (south), formerly the 3rd Battalion of LNR 4, with five companies in Austria.[86]

All the battalions had numerous intercept and DF outstations along the entire front.[86]

Owing to the Soviet advances, the regimental staff together with the 25th and 12th Companies moved to Dresden in mid February 1945. From there as the Allies advanced into Germany, the group retired to Alpine Redoubt. In order to ensure the continuity of operations, a platoon of about 70 signals personnel were formed, comprising evaluators, intercepts and communication personnel. The platoon was fully mobile, and carried the most necessary records and sufficient radio equipment for monitoring and communications purposes. It drove to Wagrain in the Northern Limestone Alps.[86] The regimental headquarters and companies followed more slowly as they were not fully mobile.

In Wagrain, the 2nd and 3rd Battalions joined the regiment, so that with the exception of the 1st Battalion, that remained in north Germany, the regiment was reassembled.[86]

After the surrender of Germany, the regiment proceeded via Zell am See and the Lake Chiemsee to the Luftwaffe concentration area at Aschbach in Austria. It was subsequently discharged.[87]

Intercept and DF Operations

In the autumn of 1940, the construction of a large Rhombic antenna system was started, and once in operation, was to orientated to the east and south-east, for the purposes of exploring the possibilities of a central high frequency intercept stations. It was put into operations only shortly before the outbreak of the war with the Soviet Union in 1941 and good results were obtained. However it was never fully manned.[87]

The distribution of intercept receivers by type for the various monitoring tasks was made on a basis of the preferences of the individual signals units. It proved most advantageous, wherever possible, to assign a complete monitoring mission to a single company or outstation.[87]

Great use was found for the HF DF, A-10F that used an Adcock antenna type. However, for a war of movement it had to be made mobile. A good DF baseline, as well as an efficient method of controlling the operations of the DF's, was essential to the accomplishment of the regiment's mission. Special care had to be taken in planning D/F control by radio, which of course involved the encoding and decoding of messages, every second counted. The assignment of several targets to one D/F station proved unworkable.[87]

Cryptanalysis

The problem of securing sufficient and well qualified cryptanalyst personnel was at all times very great, since almost all messages, that numbered between 1000-2000 per day, were enciphered. To mitigate this problem, Chi-Stelle attempted to produce and train cryptanalysts itself. It was found that cryptanalysis skills were an inborn talent, and approximately one half of the personnel trained were proved useful. The chief reason why there were never sufficient cryptanalysts available may be laid to a tendency on the part of those men to specialise in certain types of codes and ciphers. It was also usually impractical to detach cryptanalysts to the various intercept companies, which in the interested of tactical evaluation would be advantageous.[88]

Cryptanalysts were mostly employed in the W-Leitstellen, or in evaluation companies where they, as well as evaluation personnel were in close contact of Referat E, that suffered a chronic shortage of staff. The introduction of new codes and new recipher table for old codes presented constant challenges for the cryptanalysts.[88]

An average of 60% to 70% of the 2-Figure, 3-Figure and 4-Figure messages were solved. 5-Figure messages often required painstaking analysis, and when solved were often not read in time to be of any strategic or tactical value.[88]

Evaluation

- Traffic and Log Analysis for DF evaluation.[88]

- The principal duties of these sub-sections were the identification of all call signs and frequencies,[88] and the reconstruction of Russian radio networks.[89] A corollary duty was to determine the system used by the various Soviet air armies in selecting their call-signs and frequencies and to attempt prediction of those to be used in the future.[89]

- Tactical and final evaluation

- As per traffic analysis, preliminary evaluation was undertaken by a fixed intercept station and the mobile intercept companies. Traffic was the forwarded to the W-Leitstellen or the evaluation companies where the traffic was evaluated, and reports prepared that were sent to the Chi-Stelle, the Luftflotten and the Fliegerkorps. Later these battalion evaluation reports were also sent to the regimental evaluation company, where they were compiled into a comprehensive report from the Chi-Stelle, where they were edited and passed to the Luftwaffe and Wehrmacht HQ.[89]

Signal Communications

Excellent signal reception was absolutely essential to the Chi-Stelle.[89] Experience from the Russian Front showed that the dissemination of intelligence from outstations to tactical aviation units had to be accomplished in a matter of minutes, and in some cases, seconds. For this reason, R/T stations of Signals Regiment East were located directly on the aerodrome of German fighter and reconnaissance units, and had direct wire lines to the fighter control centre.[90] The out-stations were also tied to the teleprinter switchboards of the air bases in order that communication be maintained with the battalion and neighbouring R/T stations. The out-stations did not have the necessary means of installing their own telephone lines. They were furnished by the airbase commander. Radio links to the battalion were also maintained as a standby.[90]

Liaison with the Army signals

As the external characteristics of Russian radio traffic was not sufficient to identify a group of new traffic as either Red Army or Soviet Air Forces it was necessary to maintain close liaison with the German Army cipher bureau, General der Nachrichtenaufklärung. Of primary importance was liaison between the respective traffic analysis sections and for this purpose Non-commissioned liaison officers were frequently exchanged. During such periods when contact with the Army could not be maintained perhaps due to distances involved, the Luftwaffe Chi-Stelle was still able to identify traffic and execute traffic analysis.[90]

Northern sector

Development up to the Luftwaffe invasion of Russia

In May 1941, Luftflotte 2 and its attached signals units, the 3rd Battalion of the Luftwaffe Signal Regiment was transferred to Warsaw. As the signals unit has no experience in monitoring and intercepting Russian traffic, the majority of the work was undertaken by the fixed station in Warsaw. The committent of the Warsaw station increased again when W-Leit 2 was transferred to Italy in December 1942.[91] To reinforce the Warsaw station, that was not fully prepared, W-Leit 1 in Bernau, seconded approximately one-third of its cryptanalysis and evaluation personnel to the Warsaw station.[91] In the last half of 1944, the work of W-Leit 1 has attained such stature that its reports were forwarded by Referat D to the General Staff virtually unaltered.

Shortly before the beginning of the war with the Soviet Union, the 3rd Battalion of LNR 1 in Bernau moved with the Luftflotte to Königsberg. At the outbreak of World War 2, the battalion was composed of:[91]

- W-Leit 1

- Fixed station in Kobbelbude, with several out-stations

- A small intercept and DF station in Kirkenes