Charles J. Guiteau

| Charles J. Guiteau | |

|---|---|

Charles Julius Guiteau | |

| Born |

Charles Julius Guiteau September 8, 1841 Freeport, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died |

June 30, 1882 (aged 40) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Occupation | writer, lawyer |

| Political party | Republican |

| Criminal charge | Assassination of President James A. Garfield |

| Criminal penalty | Death by hanging |

| Criminal status | Executed |

| Spouse(s) | Annie Bunn (1869–1874) |

| Parent(s) | Luther Wilson Guiteau, Jane Howe Guiteau |

| Signature | |

| |

Charles Julius Guiteau (/ɡɪˈtoʊ/; September 8, 1841 – June 30, 1882) was an American writer and lawyer who was convicted of the assassination of James A. Garfield, the 20th president of the United States. Guiteau was so offended by Garfield's rejections of his various job applications that he shot him at the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station in Washington, D.C. on July 2, 1881. Garfield died two months later from infections related to the injury. In January 1882, Guiteau was sentenced to death for the crime, and was hanged five months later.

Early life and education

Guiteau was born in Freeport, Illinois, the fourth of six children of Jane August (née Howe) and Luther Wilson Guiteau,[1] whose family was of French Huguenot ancestry.[2] He moved with his family to Ulao, Wisconsin (near current-day Grafton), in 1850 and lived there until 1855,[3] when his mother died. Soon after, Guiteau and his father moved back to Freeport.[4]

He inherited $1,000 ($27,000 today) from his grandfather as a young man and went to Ann Arbor, Michigan, in order to attend the University of Michigan. Due to inadequate academic preparation, he failed the entrance examinations. Despite cramming in French and algebra at Ann Arbor High School, during which time he received numerous letters from his father concerning his progress, he quit, and in June 1860[5] joined the utopian religious sect the Oneida Community, in Oneida, New York, with which Guiteau's father already had close affiliations. According to Brian Resnick of The Atlantic, Guiteau "worshiped" the group's founder, John Humphrey Noyes, once writing that he had "perfect, entire and absolute confidence in him in all things".[6][7]

Despite the "group marriage" aspects of that sect, he was generally rejected during his five years there, and was nicknamed "Charles Gitout".[8] He left the community twice. After leaving, he went to Hoboken, New Jersey, and attempted to start a newspaper based on the Oneida religion called The Daily Theocrat.[5] This failed and he returned to Oneida, only to leave again and file lawsuits against Noyes.[7] Guiteau's father, embarrassed, wrote letters in support of Noyes, who had considered Guiteau irresponsible and insane.[9] By 1875, Guiteau's father was convinced that his son was possessed by Satan. Conversely, Guiteau himself became increasingly convinced that his actions were divinely inspired, and that his destiny was to "preach a new Gospel" like Paul the Apostle.[6]

Career

Guiteau then obtained a law license in Chicago; however, he was not successful as a lawyer. He argued only one case in court, the bulk of his business being in bill collecting. His former wife later detailed his dishonest dealings, describing how he would keep disproportionate amounts of the bill and rarely give the money to his clients.[10]

He next turned to theology. He published a book on the subject called The Truth which was almost entirely plagiarized from the work of Noyes.[11] He wandered from town to town lecturing to any and all who would listen to his religious ramblings, and in December 1877 gave a lecture at the Congregational Church in Washington, D.C.[12]

Guiteau spent the first half of 1880 in Boston, which he left owing money and under suspicion of theft.[13] On June 11, 1880, he was a passenger on the SS Stonington when it collided with the SS Narragansett at night in heavy fog. The Stonington was able to return to port, but the Narragansett burned to the waterline and sank, with significant loss of life. Although none of his fellow passengers on the Stonington were injured, the incident left Guiteau believing that he had been spared for a higher purpose.[14]

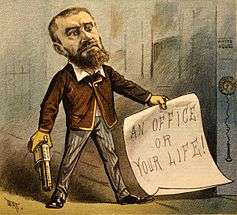

Guiteau's interest then turned to politics. He wrote a speech in support of Ulysses S. Grant called "Grant against Hancock", which he revised to "Garfield against Hancock"[15][16] after Garfield won the Republican nomination in the 1880 presidential campaign. Ultimately, he changed little more than the title and any mention of Grant in the speech itself.[17] The speech was delivered at most twice, and copies were passed out to members of the Republican National Committee at their summer 1880 meeting in New York, but Guiteau believed himself to be largely responsible for Garfield's victory.[18] He insisted he should be awarded a consulship for his supposedly vital assistance, first asking for Vienna, then deciding that he would rather have the one in Paris.[18] Guiteau's personal requests to Garfield and his cabinet as one of many job seekers who lined up every day to see them in person were continually rejected, as were his numerous letters.[18] At this time, Guiteau was destitute and forced to sneak from rooming house to rooming house without paying for his lodging and meals, and to walk around snowy Washington, D.C. in a threadbare suit, without a coat, hat or boots. He spent his days in hotel lobbies reading discarded newspapers to keep track of the schedules of Garfield and his cabinet and making use of the hotels' complimentary stationery to write them letters pressing his claim for a consulship.[19] In the spring, he was still in Washington, and on May 14, 1881, he once more encountered Secretary of State James G. Blaine in person and inquired about a consular appointment; an exasperated Blaine finally snapped "Never speak to me again on the Paris consulship as long as you live!"[18][20][6]

Assassination of Garfield

Guiteau considered himself a loyal Republican, and his narcissistic personality convinced him that his work for the party was critical to Garfield’s election to the presidency. Later convinced that Garfield was going to destroy the Republican Party by scrapping the patronage system, and after his final encounter with Blaine, he decided the only solution was to remove Garfield and elevate Vice President Chester A. Arthur (a Conkling acolyte) to the presidency.

Guiteau felt that God told him to kill the president; he felt that such an act would be a "removal" as opposed to an assassination. He also felt that Garfield needed to be killed to rid the Republican Party of Secretary of State James G. Blaine.[6] Borrowing $15 from George Maynard, a relative by marriage,[23] Guiteau went out to purchase a revolver. He knew little about firearms, but did know that he would need a large-caliber gun. While shopping at O'Meara's store in Washington, he had to choose between a .442 Webley caliber British Bulldog revolver[23] with wooden grips or one with ivory grips. He chose the one with the ivory handle because he wanted it to look good as a museum exhibit after the assassination.[24] Though he could not afford the extra dollar, the store owner dropped the price for him.[25] He spent the next few weeks in target practice – the recoil from the revolver almost knocked him over the first time he fired it[26]. The revolver was recovered after the assassination, and even photographed by the Smithsonian in the early 20th century, but it has since been lost.

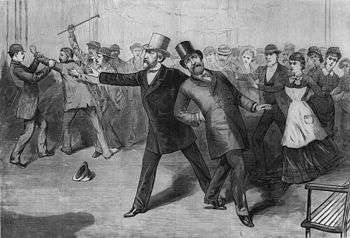

On one occasion Guiteau trailed Garfield to the railway station as the President was seeing his wife off to a beach resort in Long Branch, New Jersey, but he decided to postpone his plan because Garfield's wife, Lucretia, was in poor health and Guiteau did not want to upset her. On July 2, 1881, he lay in wait for Garfield at the since-demolished Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station, getting his shoes shined, pacing, and engaging a cab to take him to the jail later. As Garfield entered the station, looking forward to a vacation with his wife in Long Branch, Guiteau stepped forward and shot Garfield twice from behind, the second shot piercing the first lumbar vertebra but missing the spinal cord. As he surrendered to authorities, Guiteau said: "I am a Stalwart of the Stalwarts. ... [Chester A.] Arthur is president now!"[27]

After a long, painful battle with infections, possibly brought on by his doctors' poking and probing the wound with unwashed hands and non-sterilized instruments, Garfield died on September 19, eleven weeks after being shot. Most modern physicians familiar with the case state that Garfield would have easily recovered from his wounds with sterile medical care, which was common in the United States a decade later,[28] while Candice Millard argues that Garfield would have survived Guiteau's bullet wound had his doctors simply left him alone.[29] However, Garfield's biographer Allan Peskin stated that medical malpractice did not contribute to Garfield's death; the inevitable infection and blood poisoning that would ensue from a deep bullet wound resulted in damage to multiple organs and spinal bone fragmentation.[30]

Trial and execution

Once Garfield died, the government officially charged Guiteau with murder. He was formally indicted on October 14, 1881, on the charge of murder, which was previously attempted murder after his arrest. Guiteau pleaded not guilty to the charge. The trial began on November 17, 1881, in Washington, D.C. The presiding judge in the case was Walter Smith Cox. Although Guiteau would insist on trying to represent himself during the entire trial, the court appointed Leigh Robinson to defend Guiteau. In less than a week of trial, Robinson retired from the case. George Scoville then became lead counsel for the defense. While Scoville's legal experience lay in land title examination, he had married Guiteau's sister and was thus obliged to defend him in court when no one else would. Wayne MacVeagh, the U.S. Attorney General, served as the chief prosecutor. MacVeagh named five lawyers to the prosecution team: George Corkhill, Walter Davidge, retired judge John K. Porter, Elihu Root, and E.B. Smith.[31][32]

Guiteau's trial was one of the first high-profile cases in the United States where a defense based on a claim of temporary insanity was considered.[33] Guiteau vehemently insisted that while he had been legally insane at the time of the shooting (because God had taken away his free will), he was not really medically insane, which was one of the major causes of the rift between him and his defense lawyers.[34]

Edward Charles Spitzka, a leading alienist, testified as an expert witness. Spitzka had stated that it was clear "Guiteau is not only now insane, but that he was never anything else." While on the stand, Spitzka testified that he had "no doubt" that Guiteau was both insane and "a moral monstrosity".[34] Spitzka came to the conclusion that Guiteau had "the insane manner" he had so often observed in asylums, adding that Guiteau was a "morbid egotist" with "a tendency to misinterpret the real affairs of life". He thought the condition to be the result of "a congenital malformation of the brain".[35]

George Corkhill, who was the District of Columbia's district attorney and on the prosecuting team, summed up the prosecution's opinion of Guiteau's insanity defense in a pre-trial press statement that also mirrored public opinion on the issue.

He's no more insane than I am. There's nothing of the mad about Guiteau: he's a cool, calculating blackguard, a polished ruffian, who has gradually prepared himself to pose in this way before the world. He was a deadbeat, pure and simple. Finally, he got tired of the monotony of deadbeating. He wanted excitement of some other kind and notoriety... and he got it.[36]

Guiteau became something of a media sensation during his entire trial for his bizarre behavior, which included his frequently cursing and insulting the judge, most of the witnesses, the prosecution, and even his defense team, as well as formatting his testimony in epic poems which he recited at length, and soliciting legal advice from random spectators in the audience via passed notes. He dictated an autobiography to the New York Herald, ending it with a personal ad for "a nice Christian lady under 30 years of age". He was oblivious to the American public's hatred of him, even after he was almost assassinated twice himself. He frequently smiled and waved at spectators and reporters in and out of the courtroom, seemingly happy to be the center of attention for once in his life.

Guiteau sent a letter in which he argued that Arthur should set him free because he had just increased Arthur's salary by making him president.[37] At one point, Guiteau argued before Judge Cox that Garfield was killed not by the bullets but by medical malpractice ("The doctors killed Garfield, I just shot him").[38] Throughout the trial and up until his execution, Guiteau was housed at St. Elizabeths Hospital in the southeastern quadrant of Washington, D.C. While in prison and awaiting execution, Guiteau wrote a defense of the assassination he had committed and an account of his own trial, which was published as The Truth and the Removal.

To the end, Guiteau was making plans to start a lecture tour after his perceived imminent release and to run for president himself in 1884, while at the same time continuing to delight in the media circus surrounding his trial. He was found guilty on January 25, 1882.[39] After the guilty verdict was read, Guiteau stepped forward, despite his lawyers' efforts to tell him to be quiet, and yelled at the jury saying "You are all low, consummate jackasses!" plus a further stream of curses and obscenities before he was taken away by guards to his cell to await execution. Guiteau appealed his conviction, but his appeal was rejected.

29 days before his execution, Guiteau composed a lengthy poem asserting that God had commanded him to kill Garfield in order to prevent Secretary John Blaine's "scheming" to war with Chile and Peru. Guiteau also claimed in the poem that Chester A. Arthur knew the assassination had saved the United States and that Arthur's refusal to pardon him was the "basest ingratitude". Guiteau also (incorrectly) presumed that President Arthur would pressure the Supreme Court into hearing his court appeal.[40] He was hanged on June 30, 1882, in the District of Columbia, just two days before the first anniversary of the shooting.[41]

While being led to his execution, Guiteau was said to have continued to smile and wave at spectators and reporters, happy to be at the center of attention to the very end. He notoriously danced his way to the gallows and shook hands with his executioner. On the scaffold, as a last request, he recited a poem called "I am Going to the Lordy", which he had written during his incarceration. He had originally requested an orchestra to play as he sang his poem, but this request was denied.[42]

After he finished reading his poem, a black hood was placed over the smiling Guiteau's head and moments later the gallows trapdoor was sprung, the rope breaking his neck instantly with the fall.[43] Guiteau's body was not returned to his family, as they were unable to afford a private funeral, but was instead autopsied and buried in a corner of the jailyard.[43] Upon his autopsy it was discovered that Guiteau had the condition known as phimosis, an inability to retract the foreskin, which at the time was thought to have caused the insanity that led him to assassinate Garfield.[44]

With tiny pieces of the hanging rope already being sold as souvenirs to a fascinated public, rumors immediately began to swirl that jail guards planned to dig up Guiteau's corpse to meet demands of this burgeoning new market.[43] Fearing scandal, the decision was made to disinter the corpse.[45] The body was sent to the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Maryland, which preserved Guiteau's brain as well as his enlarged spleen discovered at autopsy and bleached the skeleton. These were placed in storage by the museum.[45] Parts of Guiteau's brain remain on display in a jar at the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia.[6]

Psychological assessment

Dr. Allan McLane Hamilton said in 1881 that he believed that Guiteau was sane when he assassinated Garfield.[46] An autopsy of Guiteau's brain revealed that his dura mater was abnormally thick, suggesting he may have had neurosyphillis, a disease which causes mental instability; he could have contracted the disease from a prostitute. George Paulson, formerly the chair of neurology at Ohio State University, disputed the neurosyphillis diagnosis, arguing that Guiteau suffered from both schizophrenia and "grandiose narcissism".[6]

In 2014, the criminal psychologist Kent Kiehl diagnosed Guiteau as a psychopath, giving him a score of 37.5 out of 40 on the PCL-R scale.[47]

In popular culture

The life of Guiteau, focusing on his psychological disturbances and his plan to kill Garfield, is the subject of "Portrait of an Assassin", a radio play by James Agate Jr. The play was produced as Episode 1125 of CBS Radio Mystery Theater and was first broadcast on October 8, 1980.

Guiteau is depicted in Stephen Sondheim's musical Assassins, wherein he mentors Sara Jane Moore, a woman who attempted to assassinate Gerald Ford.[48] Guiteau sings parts of "I am Going to the Lordy" in the musical's song "The Ballad of Guiteau".[49]

In the American Dad! episode "Garfield and Friends", Hayley Smith uses Guiteau's DNA to revive him. She uses him like a bloodhound to track down a revived Garfield.[50]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ "Charles Guiteau Collection". Georgetown University. February 28, 1994. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- ↑ Miller, Wilbur R. (2012). The Social History of Crime and Punishment in America: An Encyclopedia. p. 717. ISBN 1412988764

- ↑ History and origin of Port "Ulao"; Jill Hewitt; Retrieved October 5, 2007.

- ↑ Rosenberg 1968, p. 17.

- 1 2 Hayes & Hayes 1882, p. 25.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Resick, Brian. "This Is the Brain that Shot President James Garfield". The Atlantic. Retrieved August 16, 2017.

- 1 2 Ackerman 2003, p. 135.

- ↑ Rosenberg 1995, p. 19.

- ↑ Rosenberg 1995, p. 108–109.

- ↑ Hayes, H.G. A complete history of the life and trial of Charles Julius Guiteau. 1882: Philadelphia. pp. 72, 28 – via Archive.org d.

- ↑ Millard 2011, p. 116.

- ↑ "President Garfield's Assassin: Charles Guiteau's Time in Washington". Ghosts of DC. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- ↑ "BOSTON". Chicago Tribune. July 3, 1881. p. 6. Archived from the original on January 30, 2012.

- ↑ Millard 2011, Prologue.

- ↑ Alexander, H.H (1182). The life of Guiteau and the official history of the most exciting case on record. Philadelphia, PA: National Publishing Company. p. 273.

- ↑ "Garfield against Hancock Guiteau: Box 1 Folder 11 – Speech, page 1". Georgetown University. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- ↑ Bellamy, Jay (Fall 2016). "A Stalwart of Stalwarts: Garfield's Assassin Sees Deed as a Special Duty". Prologue Magazine. Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "A Stalwart of Stalwarts".

- ↑ Millard 2011, p. 127.

- ↑ Rosenberg 1968, p. 39.

- ↑ Cheney, Lynne Vincent (October 1975). "Mrs. Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper". American Heritage Magazine. 26 (6). Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- ↑ "The attack on the President's life". Library of Congress. URL retrieved on January 24, 2007.

- 1 2 "Trial Transcript: Cross-Examination of Charles Guiteau". Law2.umkc.edu. Retrieved 2013-05-25.

- ↑ Elman, Robert (1968). Fired in Anger: The Personal Handguns of American Heroes and Villains. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company. p. 166.

- ↑ June 1999, p. 24.

- ↑ Garfield's Assassin, p. 136.

- ↑ Staff (July 3, 1881) New York Herald

- ↑ Schaffer, Amanda (July 25, 2006) "A President Felled by an Assassin and 1880's Medical Care" The New York Times

- ↑ Staff (July 5, 2012). "How doctors killed President Garfield". CBS News. Retrieved 2013-05-25.

- ↑ Peskin (1978), p.607.

- ↑ Christiansen, Stephen G. "Charles Guiteau Trial: 1881 – Was Guiteau Insane?" Law Library: American Law and Legal Information

- ↑ Jackson, E. Hilton (1904). "The Trial of Guiteau". The Virginia Law Register. 9 (12): 1023–1035. doi:10.2307/1100203.

- ↑ Kennedy, Robert C. (2001). "On This Day: December 10, 1881". The New York Times. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- 1 2 Rosenberg 1995, p. 278.

- ↑ Report of the Proceedings in the Case of the United States Vs. Charles J. Guiteau. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1882. p. 979–981.

- ↑ Great American Trials 1994, pp. 187–191.

- ↑ Kuhatschek, Jack. Good News: The Meaning of the Gospel. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Connect. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-8308-6431-7.

- ↑ The doctors who treated Garfield did not wash their hands, as was common practice at the time, resulting in sepsis. See: Gilbert King, "The Stalking of the President", Smithsonian.com, January 17, 2012.

- ↑ Staff (January 26, 1882) The New York Times.

- ↑ "Charles Guiteau's reasons for assassinating President Garfield, 1882 | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History". www.gilderlehrman.org. Retrieved 2018-08-07.

- ↑ Garfield's Assassin, p. 139.

- ↑ Guiteau's poem forms the basis for the song "The Ballad of Guiteau" in Stephen Sondheim's musical Assassins; it is sung as the character cakewalks up the steps to the gallows.

- 1 2 3 Stephen G. Yanoff, The Second Mourning: The Untold Story of America's Most Bizarre Political Murder. pg. 398.

- ↑ Hodges FM (1999). "The history of phimosis from antiquity to the present". In Milos, Marilyn Fayre; Denniston, George C.; Hodges, Frederick Mansfield. Male and Female Circumcision: Medical, Legal and Ethical Considerations in Pediatric Practice. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. pp. 37–62. ISBN 0-306-46131-5.

- 1 2 Yanoff, The Second Mourning, pp. 398–399.

- ↑ W. Clark, James (2012). Defining Danger: American Assassins and the New Domestic Terrorists. Transaction Publishera. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-7658-0341-2. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ↑ Kiehl, Kent (2014). The Psychopath Wisperer: The Science of Those Without Conscience. Crown/Archetype. ISBN 9780770435851.

- ↑ Rothstein, Mervyn (January 27, 1991). "Theater: Sondheim's 'Assassins': Insane Realities of History". The New York Times. New York. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ Sondheim, Stephen (2011). Look, I Made a Hat: Collected Lyrics (1981–2011) With Attendant Comments, Amplifications, Dogmas, Harangues, Digressions, Anecdotes and Miscellany. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-30759-341-2. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- ↑ Kurland, Daniel (June 7, 2016). "American Dad: Garfield and Friends Review". Den of Geek. Retrieved August 16, 2017.

Further reading

- Ackerman, Kenneth D. (2003). Dark Horse: The Surprise Election and Political Murder of President James A. Garfield. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7867-1151-2.

- Hayes, Henry Gillespie; Hayes, Charles Joseph (1882). A Complete History of the Life and Trial of Charles Julius Guiteau, Assassin of President Garfield. Philadelphia: Hubbard Brothers.

- "Charles Guiteau Trial: 1881". Great American Trials. New England Publishing. 1994. pp. 187–191.

- "Garfield's Assassin". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. Springfield: Illinois State Historical Society. 70: 136. 1977. ISSN 0019-2287. OCLC 1588445.

- June, Dale L. (1999). Introduction to executive protection. Boca Raton: CRC Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8493-8128-7.

- "Guiteau Found Guilty". The New York Times. January 26, 1882. p. 1.

- Rosenberg, Charles E. (1968). The Trial of the Assassin Guiteau: Psychiatry and the Law in the Gilded Age. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-72717-3.

- Rosenberg, Charles E. (1995). The Trial of the Assassin Guiteau: Psychiatry and the Law in the Gilded Age (reprint, illustrated ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-72717-2.

- Millard, Candice (2011). Destiny of the Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine and the Murder of a President (Hardcover ed.). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-385-52626-5.

- Peskin, Allan (1978). Garfield: A Biography. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. ISBN 0-87338-210-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles J. Guiteau. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Works by or about Charles J. Guiteau at Internet Archive

- History House's account of Guiteau's life and the assassination of Garfield, part 1, 2 and 3.

- Guiteau, Convicted and in Jail, Declares He is Not a Lunatic, 1882 Original Letter Shapell Manuscript Foundation

- President Garfield’s Assassin: Charles Guiteau’s Time in Washington (Ghosts of DC)

- The Truth and the Removal.

- Charles J. Guiteau Collection at Georgetown University Library.

- Autograph album for the Charles J. Guiteau murder trial, MSS SC 3 at L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University

- Charles J. Guiteau at Find a Grave