Habiru

Habiru (𒄩𒁉𒊒 Ḫabiru, meaning "dusty, dirty"), sometimes written as Hapiru, is a term used in second-millennium BCE texts throughout the Fertile Crescent for people variously described as rebels, outlaws, raiders, mercenaries, bowmen, servants, slaves, and laborers. They are commonly identified with the Apiru (ʿApīru)[1][2][3][4][5]

Hapiru, Habiru and Apiru

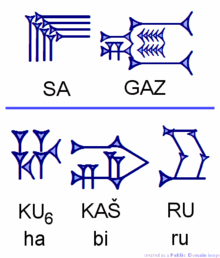

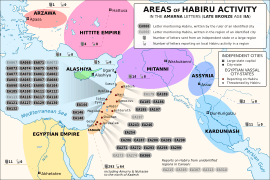

The word Habiru occurs in hundreds of second-millennium BCE documents covering a 600-year period from the 18th to the 12th centuries BCE and found at sites ranging from Egypt, Canaan and Syria, to Nuzi (near Kirkuk in northern Iraq) and Anatolia (Turkey), frequently used interchangeably with the Sumerian 𒊓𒄤 (SA.GAZ), a phonetic equivalent to the Akkadian (Mesopotamian) word saggasu ("murderer, destroyer").[6][7]

Not all Habiru were murderers and robbers:[8] one Habiru, Idrimi of Alalakh, was the son of a deposed king, and formed a band of Habiru to make himself king of Alalakh.[9] What Idrimi shared with the other Hapiru was membership of an inferior social class of outlaws, mercenaries, and slaves leading a marginal and sometimes lawless existence on the fringes of settled society.[10]

apiru had no common ethnic affiliations and no common language, their personal names being most frequently West Semitic, but many East Semitic, Hurrian or Indo-European.[10][11]

In the 18th century a north Syrian king named Irkabtum (c. 1740 BC) "made peace with [the warlord] Shemuba and his Habiru."[12]

In the Amarna tablets from 14th century BCE, the petty kings of Canaan describe them sometimes as outlaws, sometimes as mercenaries, sometimes as day-labourers and servants.[3] Usually they are socially marginal, but Rib-Hadda of Byblos calls Abdi-Ashirta of Amurru (modern Lebanon) and his son Habiru, with the implication that they have rebelled against their common overlord, the Pharaoh.[3] In "The Conquest of Joppa" (modern Jaffa), an Egyptian work of historical fiction from around 1440 BCE, they appear as brigands, and General Djehuty asks at one point that his horses be taken inside the city lest they be stolen by a passing 'Apir.[13]

Habiru and the biblical Hebrews

The biblical word "Hebrew", like Habiru, may denote a social category rather than an ethnic group.[14] Since the discovery of the second-millennium BCE inscriptions mentioning the Habiru, there have been many theories linking these to the Hebrews of the Bible, but such theories have long been disputed.[15] Most modern scholars see the Habiru/Apiru as potentially one element in an early Israel composed of many different peoples, including nomadic Shasu, the biblical Midianites, Kenites and Amalekites, runaway slaves from Egypt, and displaced peasants and pastoralists.[16]

See also

Notes

References

Citations

- ↑ Rainey 2008, p. 51.

- ↑ Coote 2000, p. 549.

- 1 2 3 McLaughlin 2012, p. 36.

- ↑ Finkelstein & Silberman 2007, p. 44.

- ↑ Noll 2001, p. 124.

- ↑ Rainey 2008, p. 52.

- ↑ Rainey 2005, p. 134-135.

- ↑ Youngblood 2005, p. 134-135.

- ↑ Naʼaman 2005, p. 112.

- 1 2 Redmount 2001, p. 98.

- ↑ Coote 2000, p. 549-550.

- ↑ Hamblin 2006, p. unpaginated.

- ↑ Mannassa 2013, p. 5,75,107.

- ↑ Blenkinsopp 2009, p. 19.

- ↑ Rainey 1995, p. 483.

- ↑ Moore & Kelle 2011, p. 125.

Bibliography

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2009). Judaism, the First Phase: The Place of Ezra and Nehemiah in the Origins of Judaism. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802864505.

- Collins, John J. (2014). A Short Introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781451484359.

- Coote, Robert B. (2000). "Hapiru, Apiru". In David Noel, Freedman; Allen C., Myers. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2007). David and Solomon: In Search of the Bible's Sacred Kings and the Roots of the Western Tradition. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780743243636.

- Hamblin, William J. (2006). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC. Routledge. ISBN 9781134520626.

- Lemche, Niels Peter (2010). The A to Z of Ancient Israel. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9781461671725.

- Manassa, Colleen (2013). Imagining the Past: Historical Fiction in New Kingdom Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199982226.

- McKenzie, John L. (1995). The Dictionary Of The Bible. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780684819136.

- McLaughlin, John L. (2012). The Ancient Near East. Abingdon Press. ISBN 9781426765506.

- Na'aman, Nadav (2005). Canaan in the Second Millennium B.C.E. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575061139.

- Noll, K.L. (2001). Canaan and Israel in Antiquity: An Introduction. A&C Black.

- Rainey, Anson F. (2008). "Who Were the Early Israelites?" (PDF). Biblical Archaeology Review. 34:06, (Nov/Dec 2008): 51–55.

- Rainey, Anson F. (1995). "Unruly Elements in Late Bronze Canaanite Society". In Wright, David Pearson; Freedman, David Noel; Hurvitz, Avi. Pomegranates and Golden Bells. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9780931464874.

- Van der Steen, Eveline J. (2004). Tribes and Territories in Transition. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 9789042913851.

- Youngblood, Ronald (2005). "The Amarna Letters and the "Habiru"". In Carnagey, Glenn A.; Schoville, Keith N. Beyond the Jordan: Studies in Honor of W. Harold Mare. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 9781597520690.