Kirati people

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Languages | |

| Kirati languages | |

| Religion | |

| Kirat Mundhum, Shamanism |

The Kirati people (Sanskrit: Kirāta)[1] (also spelled as Kirant or Kiranti) are an ethnic group of the Himalayas extending eastward from Nepal into India, Bangladesh, Burma and beyond.

Etymology

The word Kirata is a derivation from Kirati or Kiranti to name the group of people in Eastern Nepal.[2]

One school of thought says that it comes from the Sanskrit word Kirata found in the Yajurveda; they are described as the "handsome" mountain people and hunters in the forests.[3] They are described as "Kiratas" in the Mahabharata and Kirtarjuniya.[3]

History

Anatoly Yakoblave Shetenko, while on an archaeological study programme between Nepal and USSR, uncovered Kirat Stone Age tools and other artefacts from circa 30,000 B.C.[4]

According to Bista, the Kirata ("Kirat," "Kirata," and "Kiranti") are an ancient people who have been associated with the history of Nepal for thousands of years.[5] The mention of the Kirats, the ancient inhabitants of Nepal, in the Vedas and their involvement in the battles of Mahabharat indicate the historical relation and population movement between India and Nepal.[6] Some legendary sources from the Kathmandu Valley describe the Kiratas as early rulers there, taking over from earlier Gopals or Abhiras, both of whom may have been cowherding tribes.[7]

Kirati in Mahabharata

Kirātas (Sanskrit: किरात) are mentioned in early Sanskrit literature as hunter tribes from the Himalayas. They are first mentioned in the Yajurveda (Shukla XXX.16; Krisha III.4,12,1) and in the Atharvaveda (X.4,14), which dates back to 16th century BC. They are often mentioned along with the Cinas "Chinese".[8] The Kiratas in Distant Past A Sanskrit-English Dictionary refer the meaning of 'Kirat' as a 'degraded, mountainous tribe, a savage and barbarian' while other scholars attribute more respectable meanings to this term and say that it denotes people with the lion's character, or mountain dwellers.[9]

The Sanskrit kavya titled Kiratarjuniya (Of Arjuna and the Kirata) mentions that Arjuna adopted the name, nationality, and guise of a Kirata for a period to learn archery and the use of other arms from Shiva, who was considered as the deity of the Kirata.[10]

Hindu myth has many incidents where the god Shiva imitates a married Kirati girl who later become Parvati.[11] In Yoga Vasistha 1.15.5, Rama speaks of kirāteneva vāgurā "a trap [laid] by Kiratas", so about 10th century BCE, they were thought of as jungle trappers, the ones who dug pits to capture roving deer. The same text speaks of King Suraghu, the head of the Kiratas who is a friend of the Persian King, Parigha.

Modern scholarship

Contemporary historians widely agree that a widespread cultural exchange and intermarriage took place in the eastern Himalayan region between the indigenous inhabitants — called the Kirat — and the Tibetan migrant population, reaching a climax during the 8th and 9th centuries.

Another wave of political and cultural conflict between Khas and Kirat ideals surfaced in the Kirat region of present-day Nepal during the last quarter of the 18th century. A collection of manuscripts from the 18th and 19th centuries, till now unpublished and unstudied by historians, have made possible a new understanding of this conflict. These historical sources are among those collected by Brian Houghton Hodgson (a British diplomat and self-trained orientalist appointed to the Kathmandu court during the second quarter of the 19th century) and his principal research aide, the scholar Khardar Jitmohan.

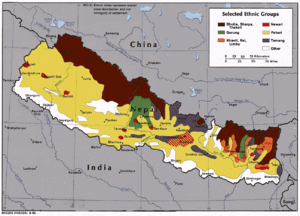

For over two millennia, a large portion of the eastern Himalaya has been identified as the home of the Kirat people, of which the majority are known today as Rai, Limbu, Sunuwar and Yakkha. In ancient times, the entire Himalayan region was known as the Kimpurusha Desha (also, Kirata Pradesh), a phrase derived from a Sanskrit term used to identify people of Kirat origin. The earliest references to the Kirat as principal inhabitants of the Himalayan region are found in the texts of Atharvashirsha and Mahabharata, believed to date to before the 9th century BC.

For over a millennium, the Kirat had inhabited the Kathmandu Valley, where they installed their own ruling dynasty. According to the history of Nepal, the Kirats ruled for about 1,225 years (800 BCE–300 CE). Their reign had 29 kings. The Kirat population in the valley along with original Australoids and Austro-Asiatic speakers form the base for later Newar population. As time passed, other Kirat groups, now known as Rai, Limbu and Sunuwar settled mostly in the Koshi region of present-day eastern Nepal and Sikkim. The Limbu people have their own distinct form of Kirat Mundhum, known as Yuma Sammang or Yumaism; they venerate a supreme goddess called Tagera Ningwaphumang .

In addition to ancestor worship, Kirati people also worship Mother Nature.

From around the 8th century, areas on the northern frontier of the Kirat region began to fall under the domination of migrant people of Tibetan origin. This flux of migration brought about the domination by Tibetan religious and cultural practices over ancient Kirat traditions. This influence first introduced shamanistic Bön practices, which in turn were later replaced by the oldest form of Tibetan Buddhism. The early influx of Bön culture to the peripheral Himalayan regions occurred only after the advent of Nyingma, the oldest Buddhist order in Lhasa and Central Tibet, which led followers of the older religion to flee to the Kirat areas for survival. The Tibetan cultural influx ultimately laid the foundation for a Tibetan politico-religious order in the Kirat regions, and this led to the emergence of two major Tibetan Buddhist dynasties, one in Sikkim and another in Bhutan. The early political order of the Kingdom of Bhutan had been established under the political and spiritual leadership of the lama Zhabs-drung Ngawang Namgyal.

Te-ongsi Sirijunga Xin Thebe

Tye-Angsi Sirijanga Singthebe was an 18th-century Limbu scholar, teacher, educator, historian, and philosopher of Limbuwan and Sikkim. Sirijanga researched and taught the Limbu script, language and religion of the Limbu's in various part of Limbuwan and Sikkim. He revived the old Sirijanga script that was developed during Kirat reign (also known as Limbu script).

History of Limbuwan: Kirat people of Limbu nationality

Limbuwan had a distinct history and political establishment until its unification with the kingdom of Gorkha in 1774 AD. During King Prithvi Narayan Shah's unification of Nepal, the present-day Nepal east of Arun and Koshi rivers was known as Pallo Kirat Limbuwan. It was divided into 10 Limbu kingdoms; Morang kingdom was the most powerful and had a central government. The capital of Morang kingdom was Bijaypur (present-day Dharan). After the Limbuwan Gorkha War and seeing the threat of the rising power of the British East India Company, the kings and ministers of all the some Yakthung laje ("thibong Yakthung laje") kingdoms of Limbuwan gathered in Bijaypur, and they agreed upon the Limbuwan-Gorkha Treaty ("Nun-Pani Sandhi"). This treaty formally merged the 10 Limbu kingdoms into the Gorkha kingdom but it also had a provision for autonomy of Limbuwan under the "kipat" system.

Kiratology

Kiratology is the study of Veda of Kirats the Mundhum along with history, cultures, languages and litaretures of Kirat ethnic people in Nepal, Darjeeling, Assam, Burma/Myanmar, Hong Kong, England and so on. The Mundhum is the book of knowledge on origin, history, culture, occupation and traditions of Kirati people. Noted scholars on Kiratology so far is Imansing Chemjong who did ground breaking contributions on kirat Mundhum, history, cultures, and languages. After Chemjong, PS Muringla, BB Muringla and Bairagi Kainla also contributed towards Kiratology.

Gorkhali hegemony

After the completion of the conquest of the Kathmandu Valley in 1769, the Gorkhali army marched east towards the Kirat territory. The Sen rulers of Limbuwan, known as Hindupati, had established a weak rule in the Kirat region by adopting a policy of mutual understanding with the local Kirat leaders. The topless bamboo tree of Budha Subba Temple of Dharan, Nepal is believed to be grown from bows and arrows left by the last Limbu king of Morang Budhhi Karna Raya Khewang when he was unable to kill an elephant with a single strike of arrow from his bow.

After the end of Rana Regime in 2007 BS (1951 AD), when power came back to Shah dynasty the autonomous power given to Limbu was reduced. King Tribhuwan demolished title of Haang (means King in Limbu language) to Subba. When King Mahendra ascended the throne he banished the law which prohibits other tribes right to buy land without permission of Subba (Head of Limbu) of particular area as well as levy and taxes to Subba in 1979.

32 Kirat Kings who ruled in Kathmandu Valley

According to Mahabharata, chronicle of Bansawali William Kirk Patrick[12] and Daniel Wright,[13] the Kirata kings of the Nepal Valley were:

- King Shree Yalamba 90years/ राजा श्री एलाम्बा - ९० वर्ष

- King Shree Palamba - 81years/राजा श्री पलाम्बा- ८१ वर्ष

- King Shree Melam - 89 years/राजा श्री मेलं - ८९ वर्ष

- King Shree Changming - 42 years/राजा श्री चंमिं - ४२ वर्ष

- King Shree Dhakang - 37 years/राजा श्री धस्कं - ३७ वर्ष

- King Shree Walangcha - 31 years 6 months/राजा श्री वलंच - ३१ वर्ष ६ महिना

- King Shree Jite Dasti - 40 years 8 months/राजा श्री जिते दस्ति - ४० वर्ष ८ महिना

- King Shree Hoorma - 50 years/राजा श्री हुरमा - ५० वर्ष

- King Shree Tooske - 41 years 8 months/राजा श्री तुस्के - ४१ वर्ष ८ महिना

- King Shree Prasaphung - 38 years 6 months/राजा श्री प्रसफुं - ३८ वर्ष ६ महिना

- King Shree Pawa: - 46 years/राजा श्री पवः - ४६ वर्ष

- King Shree Daasti - 40 years/राजा श्री दास्ती - ४० वर्ष

- King Shree Chamba - 71 years/राजा श्री चम्ब - ७१ वर्ष

- King Shree Stungko - 54 years/राजा श्री स्तुङको - ५४ वर्ष

- King Shree Swananda - 40 years 6 months/राजा श्री स्वनन्द - ४० वर्ष ६ महिना

- King Shree Phukong - 58 years/राजा श्री फुकों - ५८ वर्ष

- King Shree Singhu - 49 years 6 months/राजा श्री शिंघु - ४९ वर्ष ६ महिना

- King Shree Joolam - 73 years 3 months/राजा श्री जुलम् - ७३ वर्ष ३ महिना

- King Pagan Min - 40 years/राजा श्री लुकं - ४० वर्ष

- King Shree Thoram - 71 years/राजा श्री थोरम् - ७१ वर्ष

- King Shree Angsu Barmma - 73 years 6 months/राजा श्री अंशु वर्म्म - ७३ वर्ष ६ महिना

- King Shree Thuko - 83 years/राजा श्री थुको - ८३ वर्ष

- King Shree Gunjong - 72 years 7 months/राजा श्री गुंजं ७२ वर्ष ७ महिना

- King Shree Pushka - 81 years/राजा श्री पुस्क - ८१ वर्ष

- King Shree Tyapamee - 54 years/राजा श्री त्यपमि - ५४ वर्ष

- King Shree Moogmam - 58 years/राजा श्री मुगमम् - ५८ वर्ष

- King Shree Shasaru - 63 years/राजा श्री शसरू - ६३ वर्ष

- King Shree Goongoong - 74 years/राजा श्री गंणं - ७४ वर्ष

- King Shree Khimbung - 76 years/राजा श्री खिम्बुं - ७६ वर्ष

- King Shree Girijung - 81 years/राजा श्री गिरीजं - ८१ वर्ष

- King Shree Khurangja - 78 years/राजा श्री खुरांज - ७८ वर्ष

- King Shree khigu - 85 years/राजा श्री खिगु - ८५ वर्ष

The Yele Sambat (Yele Era) is named after Kirat King Yalambar. 32 Kirat Kings ruled in the Kathmandu valley for 1963 years 8 months. The Lichhavi dynasty dethroned the Kirat rulers in 158AD (evidence: statue of Jaya Barma found in Maligaun of Kathmandu). This means that Kirat King Yalambar's reign started BC 1779.8. If we calculate current 2018 + 1779.8 = 3797 is the Kirati new year in Maghe Sakranti in 2018 AD. New year is celebrated in Maghe Sakranti which is around mid-January (January 14-15).

Himalayan

Modern ethnic groups

In academic literature, the earliest recorded groups of the Kirati are today divided into two groups — the Rai and Limbu.[14] When the Shah kings conquered, they established the headman and jindars as local rulers and give title the Khambu as Rai, Limbu as Subba, the Sunwar as Mukhiya and the Yakkha as Dewan.[15]

The Kirat groups that today identify themselves using the nomenclature 'Kirat' include the Rai, Limbu, Sunuwar, Yakkha and few segments of the Rai people like Bahing, Kulung and speakers of Khaling, Bantawa, Chamling, Thulung, Jerung, and other related ethnic groups.[16] The tripartition of the Kirat region in Eastern Nepal documented by Hodgson, divided into three region are Wallo Kirat (Near Kirat), Majh Kirat (Middle Kirat) and Pallo Kirat (Far Kirat).[17] The region Wallo Kirat, Majh Kirat were predominant by Rai Kirat and Pallo Kirat were preponderance by Limbu Kirat as known as Limbuwan.[18] The Rai, Limbu and Yakha are different from one another and yet they all sit under one umbrella in many respects.[19]

The Kirati people and Kiranti languages between the rivers Likhu and Arun, including some small groups east of the Arun, are usually referred to as the Rai people, which is a geographic grouping rather than a genetic grouping.[20] The Sunwars inhabit the region westward of River Sun Koshi.

Other groups who claim descent from Kirat

The Kirat were among the earliest inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley and a large percentage of the Newar population is believed to have descended from them. The continuity of Newar society from the pre-Licchavi period has been discussed by many historians and anthropologists.[21][22] The language of the Newars, Nepalbhasa, a Tibeto-Burman language, is classified as a Kirati language. Similarly, the over 200 non-Sanskritic place names found in the Sanskrit inscriptions of the Licchavi period of the first millennium C.E. are acknowledged to belong to the proto-Newar language; modern variants of many of these words are still used by the Newars today to refer to geographical locations in and around Kathmandu valley.[23] Although the 14th century text Gopalarajavamsavali states that the descendants of the Kirata clan that ruled Nepal before the Licchavis resided in the region of the Tamarkoshi river,[24] a number of Newar caste and sub-caste groups and clans also claim descent from the erstwhile Kirat royal lineage.[25]

Even though most modern Newars are either Hindu or Buddhist or a mixture of the two as a result of at least two millennia of Sanskritization and practice a complicated, ritualistic religious life, vestigal non-Sanskritic elements can be seen in some of their practices that have similarities with the cultures of other Mongoloid groups in the north-east region of India.[26] Sudarshan Tiwari of Institute of Engineering, Tribhuvan University, in his essay 'The Temples of the Kirata Nepal' argues that the Newar temple technology based on brick and timber usage and the rectangular temple design used for 'Tantric' Aju and Ajima deities are pre-Licchavi in origin and reflect Newar religious values and geometrical aesthetics from the Kirati period.[27].

Dhimal, Hayu, Koch, Thami, Tharu, Chepang, and Surel ethnic groups also consider themselves to be of Kirati descent.[28]

The original inhabitants of the Dooars region of India, the Koch Rajbongshi and Mech claim to be Kiratis as do the Bodo-Kachari people tribes of Assam. They derive their titles from the original place of their dwelling, "Koch" from the Koshi river, "Mech" from the Mechi River and "Kachari" is derived from Kachar, which means "river basin". Dhimal, Hayu, Koch, Thami, Tharu, Chepang, and Surel ethnic groups also consider themselves to be of Kirati descent.[29] The basis of these claims relies on the fact that they are Mongoloids.

Religion

The Himalayan Kirat people practice Kirat Mundhum, calling it "Kirat religion".[30] In early Kirat Kingdom, Mundhum was the only law of state.[31] Kirati people worshiped nature and their ancestors, practice shamanism.[32] Kirat Limbus people believe in a supreme god called Tagera Ningwaphuma(shapeless entity appearing as a bright light), who is worshipped in earthy form as the Goddess 'Yuma Sammang' and her male counterpart 'Theba Sammang'.[33][34]

The Kirat Limbu ancestor Yuma Sammang and god of war Theba Sammang are the second most important deities. The Limbus festivals are Chasok Tangnam (Harvest Festival and worship of Goddess Yuma), Yokwa ( Worship of Ancestors), Limbu New Year's Day { Maghey Sankranti), Ke Lang, Limbu Cultural Day, Sirijanga Birthday Anniversary.[35] Kirat Rai worship (Sumnima/Paruhang) are their cultural and religious practices.[36] The names of some of their festivals are Sakela, Sakle, Tashi, Sakewa, Saleladi Bhunmidev, and Folsyandar. They have two main festivals: Sakela/Sakewa Ubhauli during planting season and Sakela/Sakewa Udhauli during the time of harvest.

Brigade of Gurkhas

The British had recruited Gorkhas ethnicity-wise; four regiments were composed of Rais and Limbus.[37] 7th Gurkha Rifles was raised in 1902 and recruited Rai and Limbu from Eastern Nepal.[38] The 10th Gurkha Rifles and the regiment maintained its assigned recruiting areas in the Rai and Limbu tribal areas of eastern Nepal as part of a broad reorganisation on 13 September 1901.[39] 11 Gorkha Rifles composed entirely of Rai-Limbu non-optees for the British Gorkhas.[40]

See also

Popular culture

On 16 November 2014, French multinational video game developer company Ubisoft launched the game Far Cry 4. This game is plotted in the fictional mountainous country of Kyrat, which is heavily inspired by the Kirati people and culture.

References

- ↑ P.543 Nationalism and Ethnicity in a Hindu Kingdom: The Politics of Culture in Contemporary Nepal, David N. Gellner, Joanna Pfaff-Czarnecka, John Whelpton Routledge, 1997

- ↑ Ithihaasa: The Mystery of His Story Is My Story of History, Bhaktivejanyana Swami Author House, 29 Jan 2013

- 1 2 P.73Researches Into the History and Civilization of the Kirātas, G. P. Singh

- ↑ Moktan Dupwangel Tamang. Book of Thu:Chen Thu:Jang, 1998, Kathmandu.

- ↑ Nepali Around the World: Emphasizing Nepali Christians of the Himalayas, Cindy L. Perry, Ekta Books, 1997

- ↑ Page 13, Ramjham, Volume 16, Press Secretary Office, 1980

- ↑ "Nepal - ANCIENT NEPAL, 500 B.C.-A.D. 700". countrystudies.us. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- ↑ P. 91 Motilal Banarsidass Publ., Dineschandra Sircar, Studies in the Religious Life of Ancient and Medieval India

- ↑ The Indian Journal of Social Work, Volume 62, Department of Publications, Tata Institute of Social Sciences in 2001

- ↑ Proceedings of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, 1874,

The great hero of the Mahabharata Arjuna adopted the name nationality and guise of a Kirata for a certain period to learn archery and the use of other arms from S'iva who was considered as the deity of the Kiratas ...

- ↑ Mahabharata, Ramayana, Puranas

- ↑ P.5 India Nepal Relations: Historical, Cultural and Political Perspective, Sanasam Sandhyarani Devi, Vij Books India Pvt Ltd, 28 Dec 2011

- ↑ P.109 History of Nepāl, Daniel Wright, Cambridge University Press, 1877

- ↑ P.509 Security and the United States: An Encyclopedia, Volume 2, Karl R. DeRouen, Paul Bellamy, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008

- ↑ P.16 Journal of Anthropological Research, Volume 11, University of New Mexico., 1955

- ↑ Slusser 1982:9-11, Hasrat 1970:xxiv-xxvii, Malla 1977:132.

- ↑ P.11 Origins and Migrations: Kinship, Mythology and Ethnic Identity Among the Mewahang Rai of East Nepal, Martin Gaenszle Mandala Book Point, 2000

- ↑ History, Culture and Customs of Sikkim, J. R. Subba, Gyan Publishing House- 2008

- ↑ Cross-Cultural Marriage: Identity and Choice, Rosemary Breger, 1 Jun 1998

- ↑ Graham Thurgood, Randy J. LaPolla The Sino-Tibetan Languages 2003 Page 505, "The Kiranti people and languages between the rivers Likhu and Arun, including some small groups east of the Arun, are usually referred to as 'Rai', which is a somewhat vague geographic grouping rather than a genetic grouping. Most Kiranti languages have less than 10,000 speakers and are threatened by extinction. Some are spoken only by elderly people. Practically all Kirati speakers are also fluent in Nepali, the language of literacy and education and the national "

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Lowdin, Per. "Food, Ritual and Society among the Newars". Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ↑ Malla, Kamal Prakash (1996) "The Profane Names of the Sacred Hillocks" in Contributions to Nepalese Studies, 23(1), pp. 1-9.

- ↑ Vajracharya, Dhanavajra and Kamal P. Malla (1985) "The Gopalarajavamsavali: A Facsimile Edition Prepared by the Nepal Research Centre in Collaboration With the National Archives, Kathmandu. With an Introduction, a Transcription, Nepal and English Translations, a Glossary and Indices", Franz Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden GMBH, Kathmandu, pp. 26, 122.

- ↑ Gellner, David N. and Declan Quigley (eds.) (1995) "Contested Hierarchies: A Collaborative Ethnography of Caste among the Newars of the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal", Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- ↑ Nepali, Gopal Singh (2015) "The Newars (An Ethno-Sociological Study of a Himalayan Community)", Mandala Book Point, Kathmandu.

- ↑ https://www.scribd.com/document/56572645/Temples-of-Kirat-Nepal

- ↑ P. 33 Nepalese Culture: Annual Journal of NeHCA, Tribhuvana Viśvavidyālaya Nepālī Itihāsa, Saṃskr̥ti, ra Purātatva Śikshaṇa Samiti, Tribhuvana Viśvavidyālaya

- ↑ P. 33 Nepalese Culture: Annual Journal of NeHCA, Tribhuvana Viśvavidyālaya Nepālī Itihāsa, Saṃskr̥ti, ra Purātatva Śikshaṇa Samiti, Tribhuvana Viśvavidyālaya

- ↑ P.238 The Routledge International Handbook of Religious Education, Derek Davis, Elena Miroshnikova Routledge, 2013

- ↑ P.238 The Routledge International Handbook of Religious Education, Derek Davis, Elena Miroshnikova Routledge, 2013

- ↑ Language of the Himalayas: An Ethnolinguistic Handbook, George Van Driem

- ↑ Eco-System And Ethnic Constellation of Sikkim, Mamata Desai, 1988

- ↑ Politics of Culture: A Study of Three Kirata Communities in the Eastern Himalayas, T.B. Subba

- ↑ P.36 Sikkim: Geographical Perspectives, Maitreyee Choudhury, Mittal Publications, 2006

- ↑ Ethnic Revival and Religious Turmoil: Identities and Representations in the Himalayas, Marie Lecomte-Tilouine, Pascale Dollfus, Oxford University Press, 2003

- ↑ Fools and infantrymen: one view of history (1923-1993), E. A. Vas, Kartikeya Publications, 1995

- ↑ 5th Infantry Brigade in the Falklands 1982, Nicholas Van der Bijl, David Aldea Leo Cooper, 2003

- ↑ records.co.uk/units/4506/10th-g

- ↑ Fools and infantrymen: one view of history (1923-1993), E. A. Vas, Kartikeya Publications, 1995

External links

- - United Kirat Rai Organization of America

- KiratRai.org - Kirat Rai organization around the world

- KiratiSaathi.com - Online kirat community

- Kirat Rai UK - Kirat Rai in UK

- Kiratraiyayokkha.com - Kirat Rai Yayokkha, Nepal

- Chumlung.org.np - Kirat Yakthung Chumlung, Nepal

- Limbulibrary.com.np - Kirat History Library Online

- Iman Singh Chemjong Iman Singh Chemjong - First Kirati Historian

- - Kirat Rai Bagdogra