Ismail Qemali

| Ismail Qemali | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st Head of Government of Albania | |

|

In office 28 November 1912 – 22 January 1914 | |

| Preceded by | Independence declared |

| Succeeded by | Fejzi Bej Alizoti |

| 1st Foreign Minister of Albania | |

|

In office 4 December 1912 – June 1913 | |

| Preceded by | None |

| Succeeded by | Myfit Libohova |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

16 October 1844 Vlorë, Albania |

| Died |

24 January 1919 (aged 74) Perugia, Italy |

| Occupation | Politics, Literature |

Ismail Qemal Bej Vlora (![]()

Biography

Ismail Qemal Vlora was born in Vlorë to the noble family of Vlora that included members such as Grand Vizier Mehmed Ferid Pasha and politician Syrja Vlora.[2][3] He completed his primary education at his hometown.[2][3] Later he attended the Greek high school Zosimea in Janina and graduated from Ottoman law school in Istanbul.[4][5] Qemali married a Greek woman and sent his children to receive an education in Greece.[6]

Early career as Ottoman bureaucrat

Qemali embarked on a career as an Ottoman civil servant reaching high government positions in European and Asian parts of the empire[4] after he moved to Istanbul in May 1860. He identified with the liberal reform wing of Midhat Pasha, the author of the Ottoman constitution (1876) with whom Qemali was a close collaborator,[4] and he became governor of several towns in the Balkans. During these years he took part in efforts for the standardization of the Albanian alphabet supporting the use of Latin characters for writing Albanian[7] and the establishment of an Albanian cultural association.

By 1877, Ismail seemed to be on the brink of important functions in the Ottoman administration, but when Sultan Abdulhamid II dismissed Midhat as prime minister, Ismail Qemali was sent into exile in western Anatolia, though the Sultan later recalled him and made him governor of Beirut. Qemali in 1892 presented the sultan with a plan for a Balkan Confederation.[8] It involved an entente between Balkan states and the empire eventually bound by mutual defense and economic development of resources agreements within a unified Great Eastern state with Turkey as its centre and return of old borders.[8] In this framework, Albania like Macedonia was not treated as a separate state but as part of Turkey.[8] In time his liberal policy recommendations caused him to fall out of favour with the Sultan again.[4] Abdulhamid II awarded Qemali the position of governor (vali) of Tripoli, however he viewed the high post as exile.[4]

Exile

In May 1900 Ismail Qemali boarded the British ambassador's yacht, claimed asylum and conveyed out of the empire were for the next eight years he lived in exile.[4] Qemali left for Athens and issued proclamations explaining his abandonment of service to the empire while Ottoman authorities were upset with his flight.[4] His interest toward the Albanian question was limited until these events and Qemali's participation in the Albanian national movement was seen as an asset among Albanian circles who would bring prestige and influence Muslim Albanians to support the cause.[9] He also worked to promote constitutional rule in the Ottoman Empire.[9] In Paris he met Faik Konitza and the two leaders worked together for a short time on Albanian issues through newspaper publications where Qemali called for Albanian unity, economic development, progress and to warn of future dangers of subjugation by Balkan states.[9] The pair fell out as Qemali found Konitza difficult to work with while Konitza found his focus of being a politician overwhelming and disapproved of his pro-Greek policy.[9] Qemali went on to found the newspaper Selamet (Salvation) published in Ottoman Turkish, Albanian and Greek which called for cooperation between Albanians and Greeks, due to both peoples having the same geopolitical interests.[9] Some Albanian activists involved in the national movement considered those views as suspicious and an instrument of Greek policy causing his popularity to wane among Albanians.[9]

At first Qemali made overtures to Austria-Hungary as the great power to assist Albanians in developing a national consciousness, founding of schools and cultivating their language and attaining autonomy.[10] Later, he became close with Italo-Albanians (Arbëreshë), shifted his leanings toward Italy and supported Italian policy for Albania to counter Austro-Hungarian territorial ambitions in the Balkans.[11] In Paris, he participated in the Congress of Ottoman Opposition (1902) organised by Prince Sabahaddin and backed his faction calling for reforms, minority rights, revolution and European intervention in the empire.[12][13] During this time Qemali's positions swung between overthrow of the sultan and increasingly backing the Albanian national movement.[12][14] He corresponded over Albania's future with Prince Albert Ghica who had designs on becoming an Albanian monarch and with Preng Doçi about the involvement of Qemali in an administrative role within a future autonomous Albania.[15] According to an unverified source, in January 1907 a secret agreement was signed between Qemali, a leader of the then Albanian national movement and the Greek government which concerned the possibility of an alliance against the Ottoman Empire. The two sides agreed that the future Greek-Albanian boundary should be located on the Acroceraunian Mountains with no Albanian armed activity in the area in exchange for Greek backing of Albanian independence.[16][17]

In Rome July 1907, Qemali gave a lengthy interview to Italian media were he called for cooperation between Balkan peoples, a "Greco-Albanian entente" and affirmed Albania as having its own language, literature, history and traditions and a right to liberty and independence.[9] He was also against Albanian cooperation with Bulgarian Macedonians and viewed their support of Albanian insurrectionists as self serving and strengthening their movement due to depletion of Albanian forces.[9] Qemali's reasons for closer ties with Greeks during this time was to gain support for Albanian independence and thwart Bulgarian ambitions in the wider Balkans region as he viewed them as a threat to Greece and northern Albania in Macedonia along with Austro-Hungarian territorial ambitions.[18][9] During his lifetime Qemali looked upon Greek culture with favour and respect, maintained friendly relations with Greeks and promoted cooperation between them and Albanians.[6] Over time however he became an Albanian nationalist and by 1912 would declare the independence of Albania.[6]

Return from exile and career as Ottoman parliamentarian

After the Young Turk Revolution of 1908 and restoration of the Ottoman constitution Qemali returned from exile and became a deputy representing Berat in the restored Ottoman Parliament, working with liberal politicians[19][20] and the British. He contributed to the Young Turk (CUP) newspaper Tanin where Qemali called for government reforms.[21] Qemali became leader of the Albanian deputies in the Ottoman parliament and did not oppose Austro-Hungarian annexation of Bosnia adding that recognition of the move should entail security guarantees for the empire in case of war with Balkan states over territory.[22] During the Ottoman countercoup of 1909 though not involved in those events he was briefly made President of the Ottoman National Assembly and led it to recognise a new government by Abdul Hamid II but was forced to leave Constantinople shortly after and fled to Greece.[23][24] Qemali wired his constituency in Vlorë telling them to acknowledge the new government and Albanians from his hometown backed him with some raiding the arms depot to support the sultan with weapons if the situation called for it.[25] A government investigation later cleared Qemali of any wrongdoing.[25]

Involvement in revolutionary activity

His political career thereafter concentrated solely on Albanian nationalism. Increasing guerilla activity in Southern Albania led to Qemali coming under suspicion from the Ottoman government during the summer months of 1909.[26] The Athens embassy of the Ottoman Empire reported that Qemali negotiated with organization financed by wealthy Albanian Tosks and Greece about forging a union.[27] Qemali returned from Athens to Istanbul after the parliament cleared him from involvement in the counter-revolutionary movement and he became leader of a group of "modern liberals" who were former members of the Ahrar party.[28] In 1910 Qemali in statements to the Austro-Hungarian ambassador criticized the Young Turk government for promoting Turks above other nationalities in the empire and their divide and rule policies regarding Albanians.[29]

During the Albanian Revolt of 1911 he traveled with Xhemal Bey of Tirana and joined leaders of the revolt at a meeting in Gerče, a village in Montenegro on 23 June.[30][31] Together they drew up the "Greçë Memorandum" that called for Albanian autonomy, schooling and language rights, recognition of Albanians, electoral freedoms and liberty, military service in Albania and other measures[30][31] which addressed their requests both to Ottoman Empire and Europe (in particular to the Great Britain).[32] In December 1911, Qemali and Hasan Prishtina convened secret meetings of Albanian political notables in Istanbul that decided to organise a future Albanian uprising.[33][34] Qemali was given the task of going to Europe to obtain support from sympathetic governments for the Albanian movement in addition to financial support and funds for buying 15,000 guns.[33][35] He met with Austro-Hungarian officials in Paris and expressed that his previous misgivings regarding them had shifted, viewed Austria-Hungary as the only defender of Albania and could rely on Albanian support if they backed Albanian geopolitical interests within a strong Ottoman state.[36] During the Albanian revolt of 1912, Qemali was part of the leadership faction that backed and advocated for Albanian autonomy within the empire during negotiations with the Ottomans.[37]

Albanian Independence

The Balkan wars marked the end of Ottoman rule in the region. In September 1912, Qemali along with Luigj Gurakuqi traveled to Bucharest to consult with the Albanian community in Romania.[38] Later he departed for Vienna and kept in touch through telegram with Austro-Hungarian officials and supported as a solution their intervention in Albania.[38] On November 12 Qemali met with officials from the Austro-Hungarian foreign ministry and they told him of their sympathies for the Albanians and their situation but could not do much due to the continuing war.[38] Foreign Minister Count Leopold Berchtold supported Qemali's views on the Albanian question and placed a boat at his disposal.[38] From Trieste, Qemali sailed to Durrës by mid November, however his stay was short due to Ottoman authorities objecting to his presence with Serb forces approaching the city and he left for Vlorë arriving there on November 26.[38][39] Meanwhile his son Ethem Bey Vlora had summoned Albanian representatives to Vlorë from all over Albania.[40]

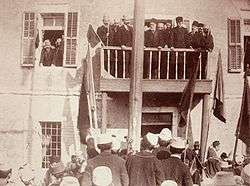

Qemali was a principal figure in the Albanian Declaration of Independence and the formation of the independent Albania on 28 November 1912.[38][40] This signaled the end of almost 500 years of Ottoman rule in Albania.[40] Together with Gurakuqi, he raised the flag on the balcony of the two-story building in Vlorë where the Declaration of Independence had just been signed. The establishment of the government was postponed for the fourth session of the Assembly of Vlorë, held on 4 December 1912, until representatives of all regions of Albania arrived to Vlorë.[41][38] The Ottoman Council of Ministers opposed his actions preferring Albanian autonomy and requested that Qemali give military assistance to the Ottoman Third Army trapped in southern Albania.[40] Aware of the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans, Qemali asked the Great Powers to recognise and support an independent Albania.[40] Qemali was prime minister of Albania from 1912 to 1914.

In November 1913, Albanian pro-Ottoman forces had offered the Albanian throne to the Ottoman war minister of Albanian origin, Izzet Pasha.[42] The Ottoman Empire sent agents to encourage a revolt, hoping to restore Ottoman suzerainty over Albania.[43] Izzet Pasha sent major Beqir Grebenali, another ethnic Albanian, to be one of his chief representatives in Albania. The Provisional Government of Albania under control of Ismail Qemali captured and executed major Beqir Grebenali. Such provocative and damaging display of independence of Qemali's government angered Great Powers and International Commission of Control forced Qemali to step aside and leave Albania.[44]

World War One and death

During World War I, Ismail Qemali lived in exile in Paris, where, though short of funds, he maintained a wide range of contacts and collaborated with the correspondent of the continental edition of the Daily Mail, Somerville Story, to write his memoirs. His autobiography, published after his death, is the only memoir of a late Ottoman statesman to be written in English and is a unique record of a liberal, multicultural approach to the problems of the dying Empire. In 1918, Ismail Qemali travelled to Italy to promote support for his movement in Albania, but was prevented by the Italian government from leaving Italy and remained as its involuntary guest at a hotel in Perugia, much to his irritation. He died of an apparent heart attack at dinner there one evening. After his death, his body was brought to Vlorë and buried in the local Tekke (Dervish convent) of the Bektashi Order.[45]

Desk and glass cabinet of Ismail Qemali, Independence Museum in Vlorë

Desk and glass cabinet of Ismail Qemali, Independence Museum in Vlorë House of Ismail Qemali in Vlorë

House of Ismail Qemali in Vlorë Grave of Ismail Qemali in Vlorë

Grave of Ismail Qemali in Vlorë- Monument of Ismail Qemali in Tiranë

Monument of Ismail Qemali in Vlorë

Monument of Ismail Qemali in Vlorë Ismail Qemali on Albanian 500 lekë banknote

Ismail Qemali on Albanian 500 lekë banknote

Cultural references and honours

Ismail Qemali is depicted on the obverses of the Albanian 200 lekë banknote of 1992–1996,[46] and of the 500 lekë banknote issued since 1996.[47] On 27 June 2012, Albanian President, Bamir Topi decorated Qemali with the Order of the National Flag (Post-mortem).[48]

1st Cabinet of Albania

- Prime Minister: Ismail Qemali

- General Secretary: Qemal Karaosmani

- Deputy Prime Minister: Dom Nikollë Kaçorri

- Minister of Foreign Affairs: Ismail Qemali, then Myfit Libohova

- Minister of Internal Affairs: Myfit Libohova, then Essad Pasha Toptani

- Minister of War: General Mehmet Pashë Dërralla

- Minister of Finance: Abdi Toptani

- Minister of Justice: Dr. Petro Poga

- Minister of Education: Dr. Luigj Gurakuqi

- Minister of Public Services: Mit’hat Frashëri

- Minister of Agriculture: Pandeli Cale, then Qemal Karaosmani

- Minister of Posts and Telegraphs: Lef Nosi

See also

References

- ↑ Giaro, Tomasz (2007). "The Albanian legal and constitutional system between the World Wars". Modernisierung durch Transfer zwischen den Weltkriegen. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Vittorio Klosterman GmbH. p. 185. ISBN 978-3-465-04017-0. Retrieved January 24, 2011.

- 1 2 Skendi 1967, pp. 182-183, 411.

- 1 2 Gawrych 2006, pp. 23-24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Skendi 1967, pp. 182-183, 331.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, p. 26, 93.

- 1 2 3 Gawrych 2006, pp. 93-94.

- ↑ Skendi 1967, p. 139.

- 1 2 3 Skendi 1967, pp. 313-314.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Skendi 1967, pp. 183-185, 331-332, 360.

- ↑ Skendi 1967, p. 269.

- ↑ Skendi 1967, pp. 269, 231-232, 332.

- 1 2 Skendi 1967, pp. 336-337.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, pp. 145-146.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, p. 205.

- ↑ Skendi 1967, pp. 330-333.

- ↑ Kondis, Basil (1976). Greece and Albania, 1908-1914. pp. 33-34.

- ↑ Pitouli-Kitsou, Hristina (1997). Οι Ελληνοαλβανικές Σχέσεις και το βορειοηπειρωτικό ζήτημα κατά περίοδο 1907- 1914 (Thesis). National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. p. 168. "Ο Ισμαήλ Κεμάλ υπογράμμιζε ότι για να επιβάλει στη σύσκεψη την άποψη του να μην επεκταθεί το κίνημα τους πέραν της Κάτω Αλβανίας, και ταυτόχρονα για να υποδείξει τον τρόπο δράσης που έπρεπε να ακολουθήσουν οι αρχηγοί σε περίπτωση που θα συμμετείχαν σ' αυτό με δική τους πρωτοβουλία και οι Νότιοι Αλβανοί, θα έπρεπε να αποφασίσει η κυβέρνηση την παροχή έκτακτης βοήθειας και να του κοινοποιήσει τις οριστικές αποφάσεις της για την προώθηση του προγράμματος της συνεννόησης, ώστε να ενισχυθεί το κύρος του μεταξύ των συμπατριωτών του. Ειδικότερα δε ο Ισμαήλ Κεμάλ ζητούσε να χρηματοδοτηθεί ο Μουχαρέμ Ρουσήτ, ώστε να μην οργανώσει κίνημα στην περιοχή, όπου κατοικούσαν οι Τσάμηδες, επειδή σ' αυτήν ήταν ο μόνος ικανός για κάτι τέτοιο. Η ελληνική κυβέρνηση, ενήμερη πλέον για την έκταση που είχε πάρει η επαναστατική δράση στο βιλαέτι Ιωαννίνων, πληροφόρησε τον Κεμάλ αρχικά στις 6 Ιουλίου, ότι ήταν διατεθειμένη να βοηθήσει το αλβανικό κίνημα μόνο προς βορράν των Ακροκεραυνίων, και εφόσον οι επαναστάτες θα επι ζητούσαν την εκπλήρωση εθνικών στόχων, εναρμονισμένων με το πρόγραμμα των εθνοτήτων. Την άποψη αυτή φαινόταν να συμμερίζονται μερικοί επαναστάτες αρχηγοί του Κοσσυφοπεδίου. Αντίθετα, προς νότον των Ακροκεραυνίων, η κυβέρνηση δεν θα αναγνώριζε καμιά αλβανική ενέργεια. Απέκρουε γι' αυτόν το λόγο κάθε συνεννόηση του Κεμάλ με τους Τσάμηδες, δεχόταν όμως να συνεργασθεί αυτός, αν χρειαζόταν, με τους επαναστάτες στηνπεριοχή του Αυλώνα."

- ↑ Blumi, Isa (2013). Ottoman refugees, 1878-1939: Migration in a post-imperial world. A&C Black. p. 82; p. 195. "As late as 1907 Ismail Qemali advocated the creation of “una liga Greco-Albanese” in an effort to thwart Bulgarian domination in Macedonia. ASAME Serie P Politica 1891–1916, Busta 665, no.365/108, Consul to Foreign Minister, dated Athens, 26 April 1907."

- ↑ Skendi 1967, pp. 360-361.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, pp. 155, 157-158, 181.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, p. 185.

- ↑ Skendi 1967, p. 359.

- ↑ Skendi 1967, p. 364.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, pp. 168, 179.

- 1 2 Gawrych 2006, p. 168.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, p. 179.

- ↑ Blumi, Isa (12 September 2013). Ottoman Refugees, 1878-1939: Migration in a Post-Imperial World. A&C Black. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-4725-1538-4.

For example, the Ottoman embassy in Athens reported that Ismail Qemali held negotiations with an organization called Hellenismos, funded by wealthy Tosks and the Greek state. This prominent ex-Ottoman governor apparently was ready to forge a union with the enemy.

- ↑ Skendi 1967, p. 400.

- ↑ Skendi 1967, pp. 402-403.

- 1 2 Skendi 1967, pp. 411, 416-417.

- 1 2 Gawrych 2006, pp. 186-187.

- ↑ Treadway, John D (1983), "The Malissori Uprising of 1911", The Falcon and Eagle: Montenegro and Austria-Hungary, 1908–1914, West Lafayette, Ind.: Purdue University Press, p. 78, ISBN 978-0-911198-65-2, OCLC 9299144, retrieved 10 October 2011

- 1 2 Skendi 1967, p. 427.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, p. 190.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, pp. 190-191.

- ↑ Skendi 1967, p. 438-439, 444-445.

- ↑ Skendi 1967, p. 437.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Skendi, Stavro (1967). The Albanian national awakening. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 458-463. ISBN 9781400847761.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, pp. 199-200.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gawrych, George (2006). The Crescent and the Eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. London: IB Tauris. p. 200. ISBN 9781845112875.

- ↑ "Essential Characteristics of the State (1912—1914)", Studia Albanica, 36, Tirana: L'Institut, 2004, p. 18, OCLC 1996482,

Essential Characteristics of the State (1912—1914) ... The setting up of the government was postponed until the fourth hearing of the Assembly of Vlora, in order to give time to other delegates from all regions of Albania to arrive.

- ↑ Elsie, Robert. "Albania under prince Wied". Archived from the original on January 25, 2011. Retrieved January 25, 2011.

pro-Ottoman forces ...were opposed to the increasing Western influence ...In November 1913, these forces, ..., had offered the vacant Albanian throne to General Izzet Pasha ... War Minister who was of Albanian origin.

- ↑ Vickers, Miranda (1999). The Albanians: a modern history. I.B.Tauris. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-86064-541-9.

... hopes of restoring Ottoman suzerainty over Albania.... sent agents to encourage insurrection

- ↑ Vickers, Miranda (1999). The Albanians: a modern history. I.B.Tauris. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-86064-541-9.

plot was discovered by Ismail Kemal's agents; one of the Porte's chief representatives, Major Beqir Grebnali... executed

- ↑ Müfid Şemsi Paşa: Arnavutluk İttihad ve Terakki, Ahmed Nezih Galitekin, Constantinople, 1995, p. 209.

- ↑ Bank of Albania. Currency: Banknotes withdrawn from circulation. – Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- ↑ Bank of Albania. Currency: Banknotes in circulation Archived 26 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine.. – Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- ↑ Republikes, Presidenti i. "Website Zyrtar". www.president.al. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

Sources

- David Barchard, The Man Who Made Albania—Ismail Kemal Bey, Cornucopia Magazine No 34, 2004.

- Ismail Kemal Bey and Sommerville Story, ed. The memoirs of Ismail Kemal Bey. London: Constable and company, 1920. (The Internet Archive, full access)

- Sommerville, A.M. (1927), Twenty years in Paris with a pen, A. Rivers ltd.

- Xoxi, Koli (1983), Ismail Qemali: jeta dhe vepra, Shtëpia Botuese "8 Nentori"

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Independence declared |

Head of State of Albania 1912–1914 |

Succeeded by William of Wied as a prince |

| Preceded by Independence declared |

Prime Minister of Albania 1912–1914 |

Succeeded by Fejzi Bej Alizoti |

| Preceded by Independence declared |

Minister of Foreign Affairs 1912–1914 |

Succeeded by |