Ottoman countercoup of 1909

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the Ottoman Empire |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Historiography |

The Ottoman countercoup of 1909 (13 April 1909) was an attempt to dismantle the Second Constitutional Era of the Ottoman Empire and replace it with an autocracy under Sultan/Caliph Abdul Hamid II. Unfortunately for the advocates of representative parliamentary government, mutinous demonstrations by disenfranchised regimental officers broke out which led to the collapse of the Ottoman government. Characterized as a counterrevolution, chaos reigned briefly and several people were killed in the confusion. It was instigated by some parts of the Ottoman Army in a large part by a certain Cypriot Islamic extremist[1] Dervish Vahdeti reigned supreme in Istanbul for 11 days. The Countercoup was put down in the 31 March Incident, on 24 April 1909 by the Army of Action (Hareket Ordusu) which was the 11th Salonika Reserve Infantry Division of to the Third Army (Ottoman Empire) commanded by Mahmud Shevket Pasha.

Name

The coup was an attempt to undermine the Young Turk Revolution of 1908, which was a coup, so it became known as the countercoup of 1909.

Events

Prelude

The Young Turk Revolution, instigated by members of the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) in the Balkan provinces, spread quickly throughout the empire and resulted in the Sultan Abdulhamid II announcing the restoration of the Ottoman constitution of 1876 on 3 July 1908. The Ottoman general election, 1908 took place during November and December 1908. The Senate of the Ottoman Empire reconvened for the first time in over 30 years on December 17, 1908 with the surviving members from the first constitutional area. The Chamber of Deputies' first session was on 30 January 1909.

For the first 10 months in power the CUP cautiously undertook to establish its control and remove the sultan as a threat.[2] In the ensuring constitutional struggle and power shift by early August 1908 the CUP managed to get the grand vizier to appoint ministers for the navy and army instead of Abdul Hamid II.[2] Palace staff to the sultan was reduced and replaced with loyal CUP members who monitored the official correspondence of Abdul Hamid II.[2] During October, several Imperial Guard units were sent to the Hijaz and Yemen resulting in a small mutiny which was put down by the government that purged some officers while replacing them with mektepli officers.[2] By March 1909 two loyal Imperial Guard battalions consisting of Albanian units were sent to Monastir (modern Bitola).[3] With the CUP gradually removing the sultan's power, these events resulted in him becoming a figurehead.[3]

The Sultan maintained his symbolic position and in March 1909 attempted to seize power once more by stirring up populist sentiment throughout the Empire. The Sultan's bid for a return to power gained traction when he promised to restore the caliphate, eliminate secular policies, and restore the sharia-based legal system. The 1908 parliament lacked coherence, most of all on the nature and unity of the organization of the Empire. While the Young Turk Revolution had promised organizational improvement, once instituted, the government at first proved itself rather disorganized and ineffectual.

Counterrevolution

Opposition grew toward the CUP as groups and individuals competed for power in the provinces and the capital.[3] On April 12 the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) declared that they no longer were a secret association and instead had become a political party.[4] During the night an uprising by armed and reactionary forces broke out that transformed into a mutiny by soldiers, most of whom were Albanians stationed in Istanbul.[4][5] One of the ringleaders was an Albanian non-commissioned officer named Hamdi Çavush.[5] A religious fundamentalist organisation Mohammedan Union were also involved in the mutiny.[4] On 13 April 1909 Army units revolted and were joined by masses of theological students, turbaned clerics shouting, "The Sheriat is in danger, we want the Sheriat" along with other elements of the population in Istanbul.[4][3] Together the crowd went to Hagia Sophia square making demands for the implementation of Sharia Law and moves toward restoring the Sultan's absolute power.[4][3] Grand vizier Hüseyin Hilmi Pasha was unable to appease the protestors and resigned his post on April 14, while the sultan replaced him with someone more in tune with the Hamidian regime.[3] During the revolt, protestors burned a few CUP offices and killed some army officers.[3] The Sultan in turn promised to bring about the rule of religion, were he to be returned to power. The leader Dervish Vahdeti reigned supreme in Istanbul for 11 days.

One of the causes of the countercoup were that several different groups were disenchanted with the changes that had come about. These included those who enjoyed patronage jobs under Abdul Hamid and had been discharged, army officers who had risen from the ranks and were no longer being favored over officers who had been to military school, and the religious scholars (ulema) who felt threatened by the more secular atmosphere and new constitution that gave equal rights to all citizens irrespective of religion.[6] Some writers have accused the British, led by Sir Gerald Fitzmaurice (1865–1939), Chief Dragoman of the British Embassy, of being the hidden hand behind this reactionary religious uprising. The British government had already supported actions against constitutionalists in an attempt to mute the effect of increasing German sympathizers in the Ottoman Empire since the 1880s.[7] Also, according to these sources, this countercoup was directed specifically against the CUP's Salonica branch, which had outmatched the British-sympathizing Monastir (Bitola) Branch.

During the countercoup, Isa Boletini along with several Kosovo Albanian chieftains offered the sultan military assistance.[5] Ismail Qemali though not involved in the countercoup events was briefly made President of the Ottoman National Assembly and led it to recognise a new government by Abdul Hamid II but was forced to leave Istanbul shortly after and fled to Greece.[8][9] Qemali wired his constituency in Vlorë telling them to acknowledge the new government and Albanians from his hometown backed him with some raiding the arms depot to support the sultan with weapons if the situation called for it.[5] A government investigation later cleared Qemali of any wrongdoing.[5] During this time however Albanian clubs telegraphed support for quelling the uprising while Prenk Bib Doda, leader of the Mirdita offered assistance from his tribe, and these sentiments where more due to fears that the Hamidian regime could return than loyalty toward the CUP.[5]

Army of Action marching on Makri Keuy (modern Bakırköy)

Army of Action marching on Makri Keuy (modern Bakırköy) Taksim Military Barracks, where the counter-coup commenced

Taksim Military Barracks, where the counter-coup commenced Counterrevolutionary prisoners of the 31 March Incident

Counterrevolutionary prisoners of the 31 March Incident Young Turk revolutionaries entering Istanbul in 1909

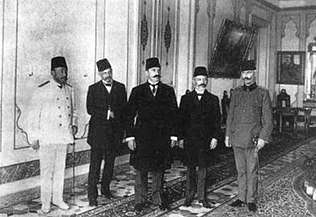

Young Turk revolutionaries entering Istanbul in 1909 Delegation to Abdul Hamid II informing him of his dethronement. Esad Pasha Toptani is the figure in centre

Delegation to Abdul Hamid II informing him of his dethronement. Esad Pasha Toptani is the figure in centre

The CUP appealed to Mahmud Shevket Pasha, commander of the Ottoman Third Army based in Salonika to quell the uprising.[3] With support from the commander of the Ottoman Second Army in Edirne, Mahmud Shevket combined the armies to create a strike force named Hareket Ordusu ("Army of Action").[3] The Army of Action numbered 20,000-25,000 Ottoman troops[3] that would be involved in events known as the 31 March Incident toward ending the coup. They were joined by 15,000 volunteers including 4,000 Bulgarians, 2,000 Greeks and 700 Jews.[3] Some Albanians supported the Army of Action.[5] Mahmud Shevket was joined by Çerçiz Topulli and Bajram Curri who brought 8,000 Albanian men and Major Ahmed Niyazi Bey with 1,800 men from Resne for military operations directed by Ali Pasha Kolonja that retook Istanbul (April 23-24) with little resistance from the mutineers.[10][3]

Aftermath

The consequences was the restoration of the constitution (for the third time; 1876, 1908 and 1909). The CUP used the events of the counterrevolution to depose Abdul Hamid II on April 27 in favor of his younger brother Mehmed V.[10][3] Four CUP members composed of one Armenian, one Jew and two Muslim Albanians went to inform the sultan of his dethronement with Essad Pasha Toptani saying "the nation has deposed you".[3] Some Muslims expressed dismay that non Muslims had informed the sultan of his deposition.[3] Abdul Hamid II reserved his anger only toward Toptani calling him a "wicked man" whom he felt betrayed him as the Albanian Toptani family had benefited from royal patronage through privileges and positions in the Ottoman system.[3] Albanians involved in the counterrevolutionary movement were executed such as Halil Bey from Krajë which caused indignation among conservative Muslims of Shkodër.[10]

References

- ↑ Muammer Kaylan. The Kemalists: Islamic Revival and the Fate of Secular Turkey. Prometheus Books, Publishers. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-61592-897-2.

- 1 2 3 4 Gawrych 2006, p. 166.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Gawrych 2006, p. 167.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Skendi 1967, p. 363-364.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Gawrych 2006, p. 168.

- ↑ Erik J. Zurcher (2003). Turkey: A Modern History. I.B. Tauris & Co.. pp. 102-103.

- ↑ G R Berridge,"Gerald Fitzmaurice (1865-1939) Chief Dragoman of the British Embassy in Turkey" Published by Martinus Nijhoff

- ↑ Skendi 1967, p. 364.

- ↑ Gawrych, George (2006). The Crescent and the Eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. London: IB Tauris. pp. 168, 179. ISBN 9781845112875.

- 1 2 3 Skendi, Stavro (1967). The Albanian national awakening. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 364-365. ISBN 9781400847761.