Islam in Kazakhstan

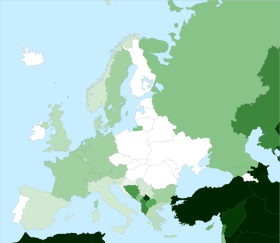

| < 1% | |

| 1–2% | |

| 2–4% | |

| 4–5% | |

| 5–10% | |

| 10–20% | |

| 30–50% | Macedonia |

| 50–70% | |

| 70–80% | Kazakhstan |

| 90–100% |

Islam is the largest religion practiced in Kazakhstan, as 70.2% of the country's population is Muslim [2] Ethnic Kazakhs are predominantly Sunni Muslims of the Hanafi school.[3] There are also small number of Shia and few Ahmadi Muslims.[4] Geographically speaking, Kazakhstan is the northernmost Muslim-majority country in the world. Kazakhs make up over half of the total population, and other ethnic groups of Muslim background include Uzbeks, Uyghurs and Tatars.[5] Islam first arrived on the southern edges of the region in the 8th century from Arabs.

History

Islam was brought to the Kazakhs during the 8th century when the Arabs arrived in Central Asia. Islam initially took hold in the southern portions of Turkestan and thereafter gradually spread northward.[6] Islam also took root due to zealous subjugation from Samanid rulers, notably in areas surrounding Taraz[7] where a significant number of Kazakhs converted to Islam. Additionally, in the late 14th century, the Golden Horde propagated Islam amongst the Kazakhs and other Central Asian tribes. During the 18th century, Russian influence rapidly increased toward the region. Led by Catherine, the Russians initially demonstrated a willingness in allowing Islam to flourish as Muslim clerics were invited into the region to preach to the Kazakhs whom the Russians viewed as "savages" and "ignorant" of morals and ethics.[8][9]

Russian policy gradually changed toward weakening Islam by introducing pre-Islamic elements of collective consciousness.[10] Such attempts included methods of eulogizing pre-Islamic historical figures and imposing a sense of inferiority by sending Kazakhs to highly elite Russian military institutions.[10] In response, Kazakh religious leaders attempted to bring religious fervor by espousing pan-Turkism, though many were persecuted as a result.[11] During the Soviet era, Muslim institutions survived only in areas where Kazakhs significantly outnumbered non-Muslims due to everyday Muslim practices.[12] In an attempt to conform Kazakhs into Communist ideologies, gender relations and other aspects of the Kazakh culture were key targets of social change.[9]

In more recent times, Kazakhs have gradually employed determined effort in revitalizing Islamic religious institutions after the fall of the Soviet Union. While not strongly fundamentalist, Kazakhs continue to identify with their Islamic faith,[13] and even more devotedly in the countryside. Those who claim descent from the original Muslim warriors and missionaries of the 8th century, command substantial respect in their communities.[14] Kazakh political figures have also stressed the need to sponsor Islamic awareness. For example, the Kazakh Foreign Affairs Minister, Marat Tazhin, recently emphasized that Kazakhstan attaches importance to the use of "positive potential Islam, learning of its history, culture and heritage."[15]

Soviet authorities attempted to encourage a controlled form of Islam under the Spiritual Administration of the Muslims of Central Asia and Kazakhstan as a unifying force in the Central Asian societies, while at the same time prohibiting true religious freedom. Since independence, religious activity has increased significantly. Construction of mosques and religious schools accelerated in the 1990s, with financial help from Turkey, Egypt, and, primarily, Saudi Arabia.[16] In 1991 170 mosques were operating, more than half of them newly built. At that time an estimated 230 Muslim communities were active in Kazakhstan. Since then the number of mosques rose to 2320 in 2013[17]. In 2012 president Kazakhstan unveiled a new Khazret Sultan Mosque in its capital, that is the biggest Muslim worship facility in Central Asia.[18]

Islam and the state

In 1990 Nursultan Nazarbayev, then the First Secretary of the Kazakhstan Communist Party, created a state basis for Islam by removing Kazakhstan from the authority of the Muslim Board of Central Asia, the Soviet-approved and politically oriented religious administration for all of Central Asia. Instead, Nazarbayev created a separate muftiate, or religious authority, for Kazakh Muslims.[19]

With an eye toward the Islamic governments of nearby Iran and Afghanistan, the writers of the 1993 constitution specifically forbade religious political parties. The 1995 constitution forbids organizations that seek to stimulate racial, political, or religious discord, and imposes strict governmental control on foreign religious organizations. As did its predecessor, the 1995 constitution stipulates that Kazakhstan is a secular state; thus, Kazakhstan is the only Central Asian state whose constitution does not assign a special status to Islam. Though, Kazakhstan joined the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation in the same year. This position was based on the Nazarbayev government's foreign policy as much as on domestic considerations. Aware of the potential for investment from the Muslim countries of the Middle East, Nazarbayev visited Iran, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia; at the same time, he preferred to cast Kazakhstan as a bridge between the Muslim East and the Christian West. For example, he initially accepted only observer status in the Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO), all of whose member nations are predominantly Muslim. The president's first trip to the Muslim holy city of Mecca, which occurred in 1994, was part of an itinerary that also included a visit to Pope John Paul II in the Vatican.[19]

See also

Further reading

- Karagiannis, Emmanuel (April 2007). "The Rise of Political Islam in Kazakhstan: Hizb Ut-Tahrir Al Islami". Nationalism and Ethnic Politics. 13 (2): 297–322. doi:10.1080/13537110701293567.

- Rorlich, Azade-Ayse (June 2003). "Islam, Identity and Politics: Kazakhstan, 1990-2000". Nationalities Papers. 31 (2): 157–176. doi:10.1080/00905990307127.

- Schwab, Wendell (June 2011). "Establishing an Islamic niche in Kazakhstan: Musylman Publishing House and its publications". Central Asian Survey. 30 (2): 227–242. doi:10.1080/02634937.2011.565229.

- Schwab, Wendell (2012). "Traditions and texts: how two young women learned to interpret the Qur'an and hadiths in Kazakhstan". Contemporary Islam. http://www.springerlink.com/content/76614876h026m165/

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mosques in Kazakhstan. |

- ↑ "Religious Composition by Country, 2010-2050". Pew Research Center. 12 April 2015. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ↑ "Kazakhstan ranks fourth among the Post-Soviet countries in terms of the number of the Muslim population, IA REGNUM reports" (in Russian). REGNUM.

- ↑ International Religious Freedom Report 2006 Archived 2008-06-22 at the Wayback Machine. U.S. Embassy in Astana, Kazakhstan

- ↑ "KAZAKHSTAN: Ahmadi Muslim mosque closed, Protestants fined 100 times minimum monthly wage". Forum 18. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ↑ Kazakhstan - International Religious Freedom Report 2009 U.S. Department of State. Retrieved on 2009-09-07.

- ↑ Atabaki, Touraj. Central Asia and the Caucasus: transnationalism and diaspora, pg. 24

- ↑ Ibn Athir, volume 8, pg. 396

- ↑ Khodarkovsky, Michael. Russia's Steppe Frontier: The Making of a Colonial Empire, 1500-1800, pg. 39.

- 1 2 Ember, Carol R. and Melvin Ember. Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender: Men and Women in the World's Cultures, pg. 572

- 1 2 Hunter, Shireen. "Islam in Russia: The Politics of Identity and Security", pg. 14

- ↑ Farah, Caesar E. Islam: Beliefs and Observances, pg. 304

- ↑ Farah, Caesar E. Islam: Beliefs and Observances, pg. 340

- ↑ Page, Kogan. Asia and Pacific Review 2003/04, pg. 99

- ↑ Atabaki, Touraj. Central Asia and the Caucasus: transnationalism and diaspora.

- ↑ inform.kz | 154837 Archived 2007-10-20 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ From the article "Kazakhstan, Islam in" in Oxford Islamic Studies Online

- ↑ "Kazakhstan leads in number of mosques in Central Asia". Retrieved 2018-01-02.

- ↑ "Kazakhs Open Huge New Mosque". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 2018-01-02.

- 1 2 Country Study - Kazakhstan Library of Congress

![]()