Islam in Korea

In South Korea, Islam (이슬람교) is a minority religion. The Muslim community is centered on Seoul and there are a few mosques around the country. According to the Korea Muslim Federation, there are about 100,000 Muslims living in South Korea, both Koreans and foreigners.[1] The Ministry of Foreign Affairs has hosted an Iftar dinner during the month of Ramadan every year since 2004.[2]

Early history

During the middle to late 7th century, Muslim traders had traversed from the Caliphate to Tang China and established contact with Silla, one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea.[3] In 751, a Chinese general of Goguryeo descent, Gao Xianzhi, led the Battle of Talas for the Tang dynasty against the Abbasid Caliphate but was defeated. The earliest reference to Korea in a non-East Asian geographical work appears in the General Survey of Roads and Kingdoms by Istakhri in the mid-9th century.[4]

The first verifiable presence of Islam in Korea dates back to the 9th century during the Unified Silla period with the arrival of Persian and Arab navigators and traders. According to numerous Muslim geographers, including the 9th-century Muslim Persian explorer and geographer Ibn Khordadbeh, many of them settled down permanently in Korea, establishing Muslim villages.[5] Some records indicate that many of these settlers were from Iraq.[6] Korean records suggest that a large number of the Muslim foreigners settled in Korea in the 9th century CE led by a man named Hasan Raza[7] Further suggesting a Middle Eastern Muslim community in Silla are figurines of royal guardians with distinctly Persian characteristics.[8] In turn, later many Muslims intermarried with Koreans. Some assimilation into Buddhism and Shamanism took place owing to Korea's geographical isolation from the Muslim world.[9]

In 1154, Korea was included in the Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi's world atlas, Tabula Rogeriana. The oldest surviving Korean world map, the Gangnido, drew its knowledge of the Western Regions from the work of Islamic geographers.[10]

Goryeo period

According to local Korean accounts, Muslims arrived in the peninsula in the year 1024 in the Goryeo kingdom, a group of some 100 Muslims, including Hasan Raza, came in September of the 15th year of Hyeonjong of Goryeo and another group of 100 Muslim merchants came the following year.[11]

Trading relations between the Islamic world and the Korean peninsula continued with the succeeding kingdom of Goryeo through to the 15th century. As a result, a number of Muslim traders from the Near East and Central Asia settled down in Korea and established families there. Some Muslim Hui people from China also appear to have lived in the Goryeo kingdom.[12]

With the Mongol armies came the so-called Saengmokin (Semu), or "colored-eye people", this group consisted of Muslims from Central Asia. In the Mongol social order, the Saengmokin occupied a position just below the Mongols themselves, and exerted a great deal of influence within the Yuan dynasty. In the Yuan dynasty, Koreans were included along with Northern Chinese, Khitan and Jurchen in the third class, as "Han ren".[13][14]

2 Japanese families, a Vietnamese family, an Arab family, a Qochanese Uyghur family, 4 Manchuria originated families, 3 Mongol families, and 83 Chinese families migrated into Korea during Goryeo.[15]

During the Yuan dynasty Korean women married Indian, Uyghur (Buddhist), and Turkic Semu men.[16] A rich merchant from the Ma'bar Sultanate, Abu Ali (Paehari) 孛哈里 (or 布哈爾 Buhaer), was associated closely with the Ma'bar royal family. After falling out with them, he moved to Yuan China and received a Korean woman as his wife and a job from the Mongol Emperor, the woman was formerly 桑哥 Sangha's wife and her father was 蔡仁揆 채송년 Chae In'gyu during the reign of 忠烈 Chungnyeol of Goryeo, recorded in the Dongguk Tonggam, Goryeosa and 留夢炎 Liu Mengyan's 中俺集 Zhong'anji.[17][18] 桑哥 Sangha was a Tibetan.[19]

It was during this period satirical poems were composed and one of them was the Sanghwajeom, the "Colored-eye people bakery", the song tells the tale of a Korean woman who goes to a Muslim bakery to buy some dumplings.

Small-scale contact with predominantly Muslim peoples continued on and off. During the late Goryeo, there were mosques in the capital Kaesong, called Yegung, whose literary meaning is a "ceremonial hall".[21]

One of those Central Asian immigrants to Korea originally came to Korea as an aide to a Mongol princess who had been sent to marry King Chungnyeol of Goryeo. Goryeo documents say that his original name was Samga but, after he decided to make Korea his permanent home, the king bestowed on him the Korean name of Jang Sunnyong. Jang married a Korean and became the founding ancestor of the Deoksu Jang clan. His clan produced many high officials and respected Confucian scholars over the centuries. Twenty-five generations later, around 30,000 Koreans look back to Jang Sunnyong as the grandfather of their clan: the Jang clan, with its seat at Toksu village.[3]

The same is true of the descendants of another Central Asian who settled down in Korea. A Central Asian named Seol Son fled to Korea when the Red Turban Rebellion erupted near the end of the Mongol's Yuan dynasty. He, too, married a Korean, originating a lineage called the Gyeongju Seol that claims at least 2,000 members in Korea.[4]

Soju

Soju was first distilled around the 13th century, during the Mongol invasions of Korea. The Mongols had acquired the technique of distilling Arak from the Muslim World[22] during their invasion of Central Asia and the Middle East around 1256, it was subsequently introduced to Koreans and distilleries were set up around the city of Kaesong. Indeed, in the area surrounding Kaesong, Soju is known as Arak-ju (hangul: 아락주).[23]

Joseon period

Study of the Huihui Lifa

In the early Joseon period, the Islamic calendar served as a basis for calendar reform owing to its superior accuracy over the existing Chinese-based calendars.[4] A Korean translation of the Huihui Lifa "Muslim System of Calendrical Astronomy", a text combining Chinese astronomy with the zij works of Jamal al-Din, was studied during the time of Sejong the Great in the 15th century.[24] The tradition of Chinese-Islamic astronomy survived in Korea up until the early 19th century.[25]

Decree against the Huihui community

In the year 1427 Sejong ordered a decree against the Huihui (Korean Muslim) community that had had special status and stipends since the Yuan dynasty. The Huihui were forced to abandon their headgear, to close down their "ceremonial hall" (Mosque in the city of Kaesong) and worship like everyone else. No further mention of Muslims exist during the era of the Joseon.[26]

Later periods

Islam was practically non-existent in Korea by the 16th century and was re-introduced in the 20th century. It is believed that many of the religious practices and teachings did not survive.[4] However, in the 19th century, Korean settlers in Manchuria came into contact with Islam once again.[27]

20th-century re-introduction

During the Korean War, Turkey sent a large number of troops to aid South Korea under the United Nations command called the Turkish Brigade. In addition to their contributions on the battlefield, the Turks also aided in humanitarian work, helping to operate war-time schools for war orphans. Shortly after the war, some Turks who were stationed in South Korea as UN peacekeepers began proselytizing Koreans. Early converts established the Korea Muslim Society in 1955, at which time the first South Korean mosque was erected.[27] The Korea Muslim Society grew large enough to become the Korea Muslim Federation in 1967.[4]

Today

Islam in South Korea

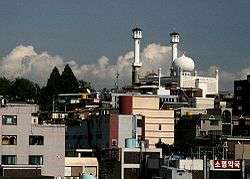

In 1962, the Malaysian government offered a grant of 33,000 USD for a mosque to be built in Seoul. However, the plan was derailed due to inflation.[4] The Seoul Central Mosque was finally built in Seoul's Itaewon neighborhood in 1976. Today there are also mosques in Busan, Anyang, Gyeonggi, Gwangju, Jeonju, Daegu and Kaesong. According to Lee Hee-Soo (Yi Huisu), president of the Korea Islam Institute, there are about 10,000 listed Muslims (mostly foreign guest workers) in South Korea.[28]

Seoul also hosts a hussainiya near Samgakji station for offering salah and memorializing the grandson of Muhammad, Husayn ibn Ali. Daegu also has a hussainiya.[29]

The Korean Muslim Federation said that it would open the first Islamic primary school, Prince Sultan Bin Abdul Aziz Elementary School, in March 2009, with the objective of helping foreign Muslims in South Korea learn about their religion through an official school curriculum. Plans are underway to open a cultural center, secondary schools and even university. Abdullah Al-Aifan, Ambassador of Saudi Arabia to Seoul, delivered $500,000 to KMF on behalf of the Saudi Arabian government.[30]

The Korean Muslim Federation provides halal certificates to restaurants and businesses. Their halal certificate is recognized by the Department of Islamic Development Malaysia (JAKIM), and there are a total of 14 KMF-halal approved restaurants in South Korea as of January 2018. [31]

Before the formal establishment of an elementary school, a madrasa named Sultan Bin Abdul Aziz Madrassa functioned since the 1990s, where foreign Muslim children were given the opportunity to learn Arabic, Islamic culture, and English.

Kuryan -the Arabic script used for writing Korean language (Hangul) has invented by Korean Muslim in 2000s

Many Muslims in Korea say their different lifestyle makes them stand out more than others in society. However, their biggest concern is the prejudice they feel after the September 11 attacks.[32] A 9-minute report was aired on ArirangTV, a Korean cable station for foreigners, on Imam Hak Apdu and Islam in Korea.[33]

Migrant workers from Pakistan and Bangladesh make up a large fraction of the Muslim population. The number of Korean Muslims was reported by The Korea Times in 2002 as 45,000[21] while the Pew Research Center estimated that there were 75,000 South Korean Muslims in 2010, or one in every five hundred people in the country.[34]

.jpg) Mosque in Itaewon.

Mosque in Itaewon.

Islam in North Korea

The Pew Research Center estimated that there were 3,000 Muslims in North Korea in 2010, up from 1,000 in 1990.[34] The Iranian embassy in Pyongyang hosts Ar-Rahman Mosque.[35]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Won-sup, Yoon. "Muslim Community Gets New Recognition". islamkorea.com. Archived from the original on June 13, 2017.

- ↑ "Foreign Minister to Host 14th Iftar Dinner". June 21, 2017. Archived from the original on June 27, 2017.

- 1 2 Grayson, James Huntley (2002). Korea: A Religious History. Routledge. p. 195. ISBN 0-7007-1605-X.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Baker, Don (Winter 2006). "Islam Struggles for a Toehold in Korea". Harvard Asia Quarterly. Archived from the original on 2007-05-17. Retrieved 2007-04-23.

- ↑ Lee (1991) reviews the writings of more than 15 Arabic geographers on Silla, which most refer to as al-sila or al-shila.

- ↑ Lee (1991, pp. 27-28) cites the writings of Dimashqi, al-Maqrisi, and al-Nuwairi as reporting Alawid emigration to Silla in the late 7th century.

- ↑ Lee (1991, p. 26) cites the 10th-century chronicler Mas'udi.

- ↑ These were found in the tomb of Wonseong of Silla, d. 798 (Kwon 1991, p. 10).

- ↑ Islamic Korea - Pravda.Ru Archived 2009-02-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Keith Pratt, Richard Rutt, James Hoare (1999). Korea: A Historical and Cultural Dictionary. Routledge. p. 36. ISBN 0-7007-0464-7.

- ↑ Haque, Dr Mozammel (3 February 2011). "Islamic Monitor: Islam and Muslims in Korea". islamicmonitor.blogspot.com.

- ↑ Keith Pratt, Richard Rutt, James Hoare (1999). Korea: A Historical and Cultural Dictionary. Routledge. p. 189. ISBN 0-7007-0464-7.

- ↑ Frederick W. Mote (2003). Imperial China 900-1800. Harvard University Press. pp. 490–. ISBN 978-0-674-01212-7. Harold Miles Tanner (12 March 2010). China: A History: Volume 1: From Neolithic cultures through the Great Qing Empire 10,000 BCE–1799 CE. Hackett Publishing Company. pp. 257–. ISBN 978-1-60384-564-9. Harold Miles Tanner (13 March 2009). China: A History. Hackett Publishing. pp. 257–. ISBN 0-87220-915-6. Peter Kupfer (2008). Youtai - Presence and Perception of Jews and Judaism in China. Peter Lang. pp. 189–. ISBN 978-3-631-57533-8. Young Kyun Oh (24 May 2013). Engraving Virtue: The Printing History of a Premodern Korean Moral Primer. BRILL. pp. 50–. ISBN 90-04-25196-0. George Qingzhi Zhao (2008). Marriage as Political Strategy and Cultural Expression: Mongolian Royal Marriages from World Empire to Yuan Dynasty. Peter Lang. pp. 24–. ISBN 978-1-4331-0275-2. Morris Rossabi (1983). China Among Equals: The Middle Kingdom and Its Neighbors, 10th-14th Centuries. University of California Press. pp. 247–. ISBN 978-0-520-04562-0.

- ↑ Haw, Stephen G. "The Semu ren in the Yuan Empire - who were they?". academia.edu.

- ↑ Kwang-gyu Yi (1975). Kinship system in Korea. Human Relations Area Files. p. 146.

- ↑ David M. Robinson (2009). Empire's Twilight: Northeast Asia Under the Mongols. Harvard University Press. pp. 315–. ISBN 978-0-674-03608-6.

- ↑ Angela Schottenhammer (2008). The East Asian Mediterranean: Maritime Crossroads of Culture, Commerce and Human Migration. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 138–. ISBN 978-3-447-05809-4.

- ↑ SEN, TANSEN. 2006. “The Yuan Khanate and India: Cross-cultural Diplomacy in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries”. Asia Major 19 (1/2). Academia Sinica: 317. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41649921?seq=17.

- ↑ http://www.sino-platonic.org/complete/spp110_wuzong_emperor.pdf p. 15.

- ↑ (Miya 2006; Miya 2007)

- 1 2 "Islam takes root and blooms". The Korea Times. 22 November 2002. Retrieved 2006-03-20.

- ↑ "Moving beyond the green blur: a history of soju". JoongAng Daily.

- ↑ "History of Soju" (in Korean). Doosan Encyclopeida. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008.

- ↑ Yunli Shi (January 2003). "The Korean Adaptation of the Chinese-Islamic Astronomical Tables". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. Springer. 57 (1): 25–60 [26–7]. doi:10.1007/s00407-002-0060-z. ISSN 1432-0657.

- ↑ Yunli Shi (January 2003). "The Korean Adaptation of the Chinese-Islamic Astronomical Tables". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. Springer. 57 (1): 25–60 [30]. doi:10.1007/s00407-002-0060-z. ISSN 1432-0657.

- ↑ "Harvard Asia Quarterly - Islam Struggles for a Toehold in Korea". archive.org. 16 May 2008.

- 1 2 "About Seoul: Way of Life". Seoul City government website. Archived from the original on February 8, 2006. Retrieved 2006-03-20.

- ↑ The article (in Korean) at "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2002-09-28. Retrieved 2005-07-19. quotes Lee Hee-Soo (Yi Hui-su), president of 한국 이슬람 학회 (Korea Islam Institute), with these figures.

- ↑ "Welcome to the Frontpage!". www.kicea.net.

- ↑ https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/nation/2008/03/117_20746.html First Muslim School to Open Next Year

- ↑ https://www.koreaexpose.com/halal-food-pyeongchang-athletes-not-visitors/ Halal Food for Pyeongchang Athletes

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-04-29. Retrieved 2008-12-19. Life is Very Hard for Korean Muslims

- ↑ 1802ibrahim (26 September 2009). "이슬람 한국 - Islam in Korea" – via YouTube.

- 1 2 "Table: Muslim Population by Country". Pew Research Center. 27 January 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ↑ Chad O'Carroll (22 January 2013). "Iran Build's Pyongyang's First Mosque". NKNews. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

Sources

- Baker, Don (Winter 2006). "Islam Struggles for a Toehold in Korea". Harvard Asia Quarterly. Archived from the original on 2007-05-17. Retrieved 2007-04-23.

- Kwon, Young-pil. (1991). Ancient Korean art and Central Asia: Non-Buddhist art prior to the 10th century. Korea Journal 31(2), 5-20.

- Lee, Hee-Soo. (1991). Early Korea-Arabic maritime relations based on Muslim sources. Korea Journal 31(2), 21-32.

External links

- Korea Muslim Federation (in Korean) (in English)

- Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology ( KAIST ) - Muslim Students Association ( MSA )

- Islamic Center & Masjid of Daejeon

- Cheonju Masjid

- Islam and Muslims in South Korea

- Collections of Korean Muslim Sermons (Audio)

- “난 한국인 무슬림이다” (in Korean) - Introducing Korean Muslim communities (Part 1) by The Hankyoreh

- ‘코슬림’ 알리 “내 나라는 코리아” (in Korean) - Introducing Korean Muslim communities (Part 2) by The Hankyoreh