Uyghur Khaganate

| Uyghur Khaganate | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 744–840[1] | |||||||||||||

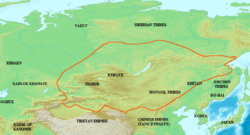

The Uyghur Khaganate at its greatest extent | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Ordu Baliq | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Old Uyghur language | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Tengrism, Manicheism, Buddhism | ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Uyghur Khagans | |||||||||||||

• 744–747 | Qutlugh Bilge Köl | ||||||||||||

• 841–847 | Öge Khan | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

• Established | 744 | ||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 840[1] | ||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

| 800[2][3] | 3,100,000 km2 (1,200,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of |

Mongolia PRC Kazakhstan Russia | ||||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Kazakhstan | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Ancient | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Khanates | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Colonization and post-nomadic period | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Topics | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| History of Mongolia | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ancient period

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Medieval period

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Modern period

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

The Uyghur Khaganate (or Uyghur Empire or Uighur Khaganate or Toquz Oghuz Country) (Modern Uyghur: ئورخۇن ئۇيغۇر خانلىقى), (Tang era names, with modern Hanyu Pinyin: traditional Chinese: 回鶻; simplified Chinese: 回鹘; pinyin: Huíhú or traditional Chinese: 回紇; simplified Chinese: 回纥; pinyin: Huíhé) was a Turkic empire[7] that existed for about a century between the mid 8th and 9th centuries. They were a tribal confederation under the Orkhon Uyghur (回鶻) nobility, referred to by the Chinese as the Jiu Xing ("Nine Clans"), a calque of the name Toquz Oghuz or Toquz Tughluq.[8]

History

Rise

In 657 the Western Turkic Khaganate was defeated by the Tang dynasty, after which the Uyghurs defected to the Tang. Prior to this the Uyghurs had already shown an inclination towards alliances with the Tang when they fought with them against the Tibetans and Turks in 627.[9][10]

In 742, the Uyghurs, Karluks, and Basmyls rebelled against the Second Turkic Khaganate.[11]

In 744 the Basmyls captured the Turk capital of Otukan and killed the reigning Özmiş Khagan. Later that year a Uyghur-Karluk alliance formed against the Basmyls and defeated them. Their khagan was killed and the Basmyls ceased to exist as a people. Hostilities between the Uyghurs and Karluks then forced the Karluks to migrate west into Zhetysu and conflict with the Turgesh, whom they defeated and conquered in 766.[12]

The Uyghur leader was from the Yaghlakar clan (Old Turkic language: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

In 745 the Uyghurs killed the last khagan of the Göktürks, Baimei Kagan Cooloon bey, and sent his head to the Tang.[14]

Golden Age

In 747, the Qutlugh Bilge Köl Kaghan died, leaving his youngest son, Bayanchur Khan to reign as Khagan El etmish bilge "State settled, wise". After building a number of trading outposts with the Tang, Bayanchur Khan used the profits to construct the capital, Ordu-Baliq, and another city further up the Selenga River, Bai Baliq. The new khagan then embarked on a series of campaigns to bring all the steppe peoples under his banner. During this time the Empire expanded rapidly and brought the Sekiz Oghuz, Kyrgyz, Karluks, Turgesh, Toquz Tatars, Chiks and the remnants of the Basmyls under Uyghur rule.

In 755 An Lushan instigated a rebellion against the Tang dynasty and Emperor Suzong of Tang turned to Bayanchur Khan for assistance in 756. The khagan agreed and ordered his eldest son to provide military service to the Tang emperor. Approximately 4,000 Uyghur horsemen assisted Tang armies in retaking Chang'an and Luoyang in 757. After the battle at Luoyang the Uyghurs looted the city for three days and only stopped after large quantities of silk were extracted. For their aid, the Tang sent 20,000 rolls of silk and bestowed them with honorary titles. In addition the horse trade was fixed at 40 rolls of silk for every horse and Uyghurs were given "guest" status while staying in Tang China.[11][15] The Tang and Uyghurs conducted an exchange marriage. Bayanchur Khan married Princess Ninguo while a Uyghur princess was married to a Tang prince.[14]

In 758, the Uyghurs turned their attentions to the northern Yenisei Kyrgyz. Bayanchur Khan destroyed several of their trading outposts before slaughtering a Kyrgyz army and executing their Khan.[15]

In 759 the Uyghurs attempted to assist the Tang in stamping out the rebels but failed. Bayanchur Khan died and his son Tengri Bögü succeeded him as Khagan Qutlugh Tarkhan sengün.[15]

In 762 Tengri Bögü planned to invade the Tang with 4,000 soldiers but after negotiations switched sides and assisted them in defeating the rebels at Luoyang. After the battle the Uyghurs looted the city. When the people fled to Buddhist temples for protection, the Uyghurs burnt them down, killing over 10,000. For their aid, the Tang was forced to pay 100,000 pieces of silk to get them to leave.[16] During the campaign the khagan encountered Manichaean priests who converted him to Manichaeism. From then on the official religion of the Uyghur Khaganate became Manichaeism.[17]

Decline

In 779 Tengri Bögü planned to invade the Tang dynasty based on the advice of his Sogdian courtiers. However, Tengri Bögü's uncle, Tun Bagha Tarkhan, opposed this plan: "Tun Bagha became annoyed and attacked and killed him and, at the same time, massacred nearly two thousand people from among the kaghan's family, his clique and the Sogdians.[18] Tun Bagha Tarkhan ascended the throne with the title Alp Qutlugh Bilge ("Victorious, glorious, wise") and enforced a new set of laws, which he designed to secure the unity of the khaganate. During his reign Manichaeism was suppressed, but his successors restored it as the official religion.[19]

In 780 a group of Uyghurs and Sogdians was killed while leaving Chang'an with tribute. Tun demanded 1,800,000 strings of cash in compensation and the Tang agreed to pay this amount in gold and silk.[20]

In 789 Tun Bagha Tarkha died and his son, To-lo-ssu, succeeded him. The Karluks took this opportunity to encroach on Uyghur territory and annexed the Futu valley.[21]

In 790 the Uyghurs and Tang forces were defeated by the Tibetans at Ting Prefecture (Beshbalik).[10] Tolossu died and his son, A-ch'o, succeeded him as Qutlugh Bilge.

In 795 Qutlugh Bilge died and the Yaghlakar dynasty came to an end. A general named also called Qutlugh declared himself the new khagan, under the title Tängridä ülüg bulmïsh alp kutlugh ulugh bilgä kaghan ("Greatly born in moon heaven, victorious, glorious, great and wise Kaghan"),[11] founding a new dynasty, the Ediz (Chinese: A-tieh).

In 803 the Uyghurs captured Qocho.[22]

In 808 Qutlugh died and his son Pao-i succeeded him. In the same year the Uyghurs seized Liang Prefecture from the Tibetans.[23]

In 821 Pao-i died and his son Ch'ung-te succeeded him. Ch'ung-te was considered the last great khagan of the Uyghur Khaganate and bore the title Kün tengride ülüg bulmïsh alp küchlüg bilge ("Greatly born in sun heaven, victorious, strong and wise"). His achievements included improved trade up with the region of Sogdia, and on the battlefield he repulsed a force of invading Tibetans in 821.

In 822 the Uyghurs sent troops to help the Tang in quelling rebels. The Tang refused the offer but had to pay them 70,000 pieces of silk to go home.[20]

In 823 the Tibetan Empire waged war on the Uyghurs.[24]

In 824 Ch'ung-te died and was succeeded by a brother, Qasar.

In 832 Qasar was murdered. He was succeeded by the son of Ch'ung-te, Hu. In the same year the Tibetan Empire ceased to make war on the Uyghurs.[24]

Fall

In 839 Hu was forced to commit suicide and a minister named Kürebir seized the throne with the help of 20,000 Shatuo horsemen from Ordos. In the same year there was a famine and an epidemic, with a particularly severe winter that killed much of the livestock the Uyghur economy was based on.[25]

In 840, one of nine Uyghur ministers, Kulug Bagha, rival of Kurebir, fled to the Yenisei Kyrgyz and invited them to invade from the north. With a force of around 80,000 horsemen, they sacked the Uyghur capital at Ordu-Baliq, razing it to the ground.[1] The Kyrgyz captured the Uyghur Khagan, Kürebir (Hesa), and promptly beheaded him. They went on to destroy other cities throughout the Uyghur empire, burning them to the ground. Öge, son of Qasar, became khagan of the defeated Uyghur khaganate.

In 841 Öge led the Uyghurs in an invasion of Shaanxi.

In 843 a Tang army led by Shi Xiong attacked the Uyghurs displaced by the fall of their khaganate and slaughtered 10,000 Uyghurs on February 13, 843 at "Kill the Foreigners" Mountain (Shahu).[26][27]

In 847 the last Uyghur khagan, Öge, was killed after having spent his six-year reign fighting the Kyrgyz, the supporters of his rival Ormïzt, a brother of Kürebir, and Tang dynasty troops in Ordos and Shaanxi. [1][17]

Successors

After the fall of the Uyghur Khaganate, the Uyghurs migrated south and established the Ganzhou Uyghur Kingdom in modern Gansu[28] and the Kingdom of Qocho near modern Turpan. The Uyghurs in Qocho converted to Buddhism, and, according to Mahmud al-Kashgari, were "the strongest of the infidels" while the Ganzhou Uyghurs were conquered by the Tangut people in the 1030s.[29]

In 1209, The Qocho ruler Baurchuk Art Tekin declared his allegiance to Genghis Khan, and the Uyghurs became important civil servants in the later Mongol Empire, which adapted the Old Uyghur alphabet as its official script. According to the New Book of Tang, a third group went to seek refuge among the Karluks.[30] The Karluks, together with other tribes such as the Chigils and Yagmas, later founded the Kara-Khanid Khanate (940–1212). Some historians associate the Karakhanids with the Uyghurs as the Yaghmas were linked to the Toquz Oghuz. Sultan Satuq Bughra Khan, believed to be a Yagma from Artux, converted to Islam in 932 and seized control of Kashgar in 940, giving rise to the new Dynasty, known as Karakhanids.[31]

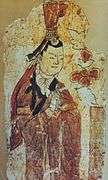

Race

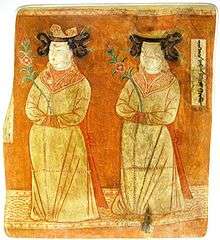

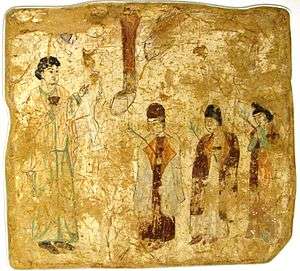

Professor James A. Millward described the original Uyghurs as phenotypically East Asian in appearance, before they began to mix with the Caucasoid inhabitants of the Tarim Basin. Millward gives as an example the images of the "Uyghur patrons" at temple 9 in the Bezeklik caves.[32]

Relationship with the Sogdians

In order to control trade along the Silk Road, the Uyghurs established a trading relationship with the Sogdian merchants who controlled the oases of Turkestan. As described above, the Uyghur adoption of Manichaeism was one aspect of this relationship—choosing Manichaeism over Buddhism may have been motivated by a desire to show independence from Tang influence.[33] It must be noted that not all Uyghurs supported conversion—an inscription at Ordu-Baliq states that Manichaens tried to divert people from their ancient shamanistic beliefs.[34] A rather partisan account from a Uyghur-Manichaen text of that period demonstrates the unbridled enthusiasm of the khaghan for Manichaeism:

"At that time when the divine Bogu Khan had thus spoken, we the Elects of all the people living within the land rejoiced. It is impossible to describe this ourjoy. The people told the story to one another and rejoiced. At that time, groups of thousands and tens of thousands assembled and with pastimes of all sorts they entertained themselves even unto dawn. And at the break of the day they made a short fast. The divine ruler Bogu Khan and all the elects of his retinue mounted on horses, and all the princes and the princesses led by those of high repute, the big and the small, the whole people, amidst great rejoicing proceeded to the gate of the city. And when the divine ruler had entered the city, he put the crown on his head... and sat upon the golden throne."

— Uyghur-Manichaen text.[34]

As conversion was based on political and economic concerns regarding trade with the Sogdians, it was driven by the rulers and often encountered resistance in lower societal strata. Furthermore, as the khaghan's political power depended on his ability to provide economically for his subjects, "alliance with the Sogdians through adopting their religion was an important way of securing this objective."[33] Both the Sogdians and the Uyghurs benefited enormously from this alliance. The Sogdians enabled the Uyghurs to trade in the Western Regions and exchange silk from China for other goods. For the Sogdians it provided their Chinese trading communities with Uyghur protection. The 5th and 6th centuries saw a large emigration of Sogdians to China. The Sogdians were main traders along the Silk Roads, and China was always their biggest market. Among the paper clothing found in the Astana cemetery near Turfan is a list of taxes paid on caravan trade in the Gaochang kingdom in the 620s. The text is incomplete, but out of the 35 commercial operations it lists, 29 involve a Sogdian trader.[35] Ultimately both rulers of nomadic origin and sedentary states recognized the importance of merchants like the Sogdians and made alliances to further their own agendas in controlling the Silk Roads.

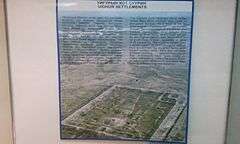

Karabalghasun

The Uyghurs created an empire with clear Persian influences, particularly in areas of government.[36] Soon after the empire was founded, they emulated sedentary states by establishing a permanent, settled capital, Karabalghasun (Ordu-Baliq), built on the site of the former Göktürk imperial capital, northeast of the later Mongol capital, Karakorum. The city was a fully fortified commercial center, typical along the Silk Road, with concentric walls and lookout towers, stables, military and commercial stores, and administrative buildings. Certain areas of the town were allotted for trade and handcrafts, while in the center of the town were palaces and temples, including a monastery. The palace had fortified walls and two main gates, as well as moats filled with water and watchtowers.

The khaghan maintained his court there and decided the policies of the empire. With no fixed settlement, the Xiongnu had been limited in their acquisition of Chinese goods to what they could carry. As stated by Thomas Barfield, "the more goods a nomadic society acquired the less mobility it had, hence, at some point, one was more vulnerable trying to protect a rich treasure house by moving it than by fortifying it."[36] By building a fixed city, the Uyghurs created a protected storage space for trade goods from China. They could hold a stable, fixed court, receive traders, and effectively cement their central role in Silk Road exchange.[36] However, the vulnerability that came with having a fixed city was to be the downfall of the Uyghurs.[33]

List of Uyghur Khagans

The following list is based on Denis Sinor, "The Uighur Empire of Mongolia," Studies in Medieval Inner Asia, Variorum, 1997, V: 1-25. Because of the complex and inconsistent Uyghur and Chinese titulatures, references to the rulers now typically include their number in the sequence, something further complicated by the non-inclusion of an unnamed ephemeral son of 4 between 5 and 6 in 790, and the inclusion of a spurious reign between 7 and 9.

- 744–747 Qutlugh bilge köl (Kuli Peile)

- 747–759 Bayanchur Khan (Bayan Chur, Moyanchuo), son of 1

- 759–779 Qutlugh tarqan sengün (Tengri Bögü, Dengli Moyu), son of 2

- 779–789 Alp qutlugh bilge (Tun bagha tarkhan), son of 1

- 789–790 Ai tengride bulmïsh külüg bilge (To-lo-ssu), son of 4

- 790–795 Qutlugh bilge (Achuo), son of 5

- 795–808 Ai tengride ülüg bulmïsh alp qutlugh ulugh bilge (Qutlugh)

- 805–808 Ai tengride qut bulmïsh külüg bilge (spurious reign: tenure belongs to 7, name to 9)

- 808–821 Ai tengride qut bulmïsh külüg bilge (Baoyi), son of 7

- 821–824 Kün tengride ülüg bulmïsh alp küchlüg bilge (Chongde), son of 9

- 824–832 Ai tengride qut bulmïsh alp bilge (Qasar), son of 9

- 832–839 Ai tengride qut bulmïsh alp külüg bilge (Hu), son of 10

- 839–840 Kürebir (Hesa), usurper

- 841–847 Öge, son of 9

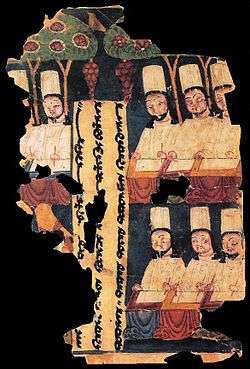

Images of Buddhist and Manichean Uyghurs

Images of Buddhist and Manichean Uyghurs from the Bezeklik caves and Mogao grottoes.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 "History of Central Asia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ↑ Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D (December 2006). "East-West Orientation of Historical Empires". Journal of world-systems research. 12 (2): 222. ISSN 1076-156X. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ Rein Taagepera (September 1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia". International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 493. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ Marshall Cavendish Corporation (2006). Peoples of Western Asia. p. 364.

- ↑ Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (2007). Historic Cities of the Islamic World. p. 280.

- ↑ Borrero, Mauricio (2009). Russia: A Reference Guide from the Renaissance to the Present. p. 162.

- ↑ Benson 1998, p. 16-19.

- ↑ Bughra 1983, p. 50-51.

- ↑ Latourette 1964, p. 144.

- 1 2 Haywood 1998, p. 3.2.

- 1 2 3 Sinor 1990, p. 317-342.

- ↑ Sinor 1990, p. 349.

- ↑ Xin Tangshu 新唐書 New Book of Tang, chapter 217 part 1 - Original text: 東極室韋,西金山,南控大漠,盡得古匈奴地。

- 1 2 Barfield 1989, p. 151.

- 1 2 3 Barfield 1989, p. 152.

- ↑ Barfield 1989, p. 152-153.

- 1 2 Bosworth 2000, p. 70.

- ↑ Asimov 1998, p. 194.

- ↑ Barfield 1989, p. 153.

- 1 2 Barfield 1989, p. 154.

- ↑ Jiu Tangshu 舊唐書 Old Book of Tang, chapter 195 - Original text: 葛祿乘勝取回紇之浮圖川,回紇震恐,悉遷西北部落羊馬於牙帳之南以避之。 Translation The Karluks took the opportunity to win control of Uyghur's Fu-tu valley; the Uyghurs, shaken with fear, moved their north-western tribes, with sheep and horses, to the south of the capital to escape. (In Xin Tangshu, Fu-tu valley (浮圖川) was referred to as Shen-tu Valley 深圖川)

- ↑ Bregel 2003, p. 20.

- ↑ Wang 2013, p. 184.

- 1 2 Wang 2013, p. 187.

- ↑ Tangshu 新唐書 New Book of Tang, chapter 217 part 2 - Original text: 方歲饑,遂疫,又大雪,羊、馬多死

- ↑ Drompp 2005, p. 114.

- ↑ John W. Dardess (10 September 2010). Governing China: 150-1850. Hackett Publishing. pp. 32–. ISBN 978-1-60384-447-5.

- ↑ Golden 2011, p. 47.

- ↑ Millward 2007, p. 50.

- ↑ Xin Tangshu Original text: 俄而渠長句錄莫賀與黠戛斯合騎十萬攻回鶻城,殺可汗,誅掘羅勿,焚其牙,諸部潰其相馺職與厖特勒十五部奔葛邏祿,殘眾入吐蕃、安西。 Translation: Soon the great chief Julumohe and the Kirghiz gathered a hundred thousand riders to attack the Uyghur city; they killed the Kaghan, executed Jueluowu, and burnt the royal camp. All the tribes were scattered—its ministers Sazhi and Pang Tele with fifteen clans fled to the Karluks, the remaining multitude went to Turfan and Anxi.

- ↑ Sinor 1990, p. 355-357.

- ↑ Millward 2007, p. 43.

- 1 2 3 Sinor 1990.

- 1 2 Roemer (editor), Prof. R (1984). The Uighur Empire of Mongolia (chapter 5) in Guo ji zhongguo bian jiang xue shu hui yi lun wen chu gao. Taibei.

- ↑ de la Vaissière, Étienne. "Sogdians in China: a short history and some new discoveries".

- 1 2 3 Barfield 1992.

Bibliography

- Asimov, M.S. (1998), History of civilizations of Central Asia Volume IV The age of achievement: A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century Part One The historical, social and economic setting, UNESCO Publishing

- Barfield, Thomas (1989), The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China, Basil Blackwell

- Benson, Linda (1998), China's last Nomads: the history and culture of China's Kazaks, M.E. Sharpe

- Bregel, Yuri (2003), An Historical Atlas of Central Asia, Brill

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (2000), The Age of Achievement: A.D. 750 to the End of the Fifteenth Century - Vol. 4, Part II : The Achievements (History of Civilizations of Central Asia), UNESCO Publishing

- Bughra, Imin (1983), The history of East Turkestan, Istanbul: Istanbul publications

- Drompp, Michael Robert (2005), Tang China And The Collapse Of The Uighur Empire: A Documentary History, Brill

- Golden, Peter B. (2011), Central Asia in World History, Oxford University Press

- Haywood, John (1998), Historical Atlas of the Medieval World, AD 600-1492, Barnes & Noble

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott (1964), The Chinese, their history and culture, Volumes 1-2, Macmillan

- Mackerras, Colin (1990), "Chapter 12 - The Uighurs", in Sinor, Denis, The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Cambridge University Press, pp. 317–342, ISBN 0 521 24304 1

- Millward, James A. (2007), Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang, Columbia University Press

- Mackerras, Colin, The Uighur Empire: According to the T'ang Dynastic Histories, A Study in Sino-Uighur Relations, 744-840. Publisher: Australian National University Press, 1972. 226 pages, ISBN 0-7081-0457-6

- Rong, Xinjiang (2013), Eighteen Lectures on Dunhuang, Brill

- Sinor, Denis (1990), The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-24304-9

- Xiong, Victor (2008), Historical Dictionary of Medieval China, United States of America: Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 0810860538

- Xue, Zongzheng (1992), Turkic peoples, 中国社会科学出版社

Further reading

- Jiu Tangshu (舊唐書) Old Book of Tang Chapter 195 (in Chinese)

- Xin Tangshu (新唐書) New Book of Tang, chapter 217, part 1 and part 2 (in Chinese). Translation in English here (most of part 1 and beginning of part 2).

- Die chinesische Inschrift auf dem uigurischen Denkmal in Kara Balgassun (1896)